This document provides information about the third edition of the book "Creating Web Sites Bible" published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. It was written by Philip Crowder with David A. Crowder. Some key details include:

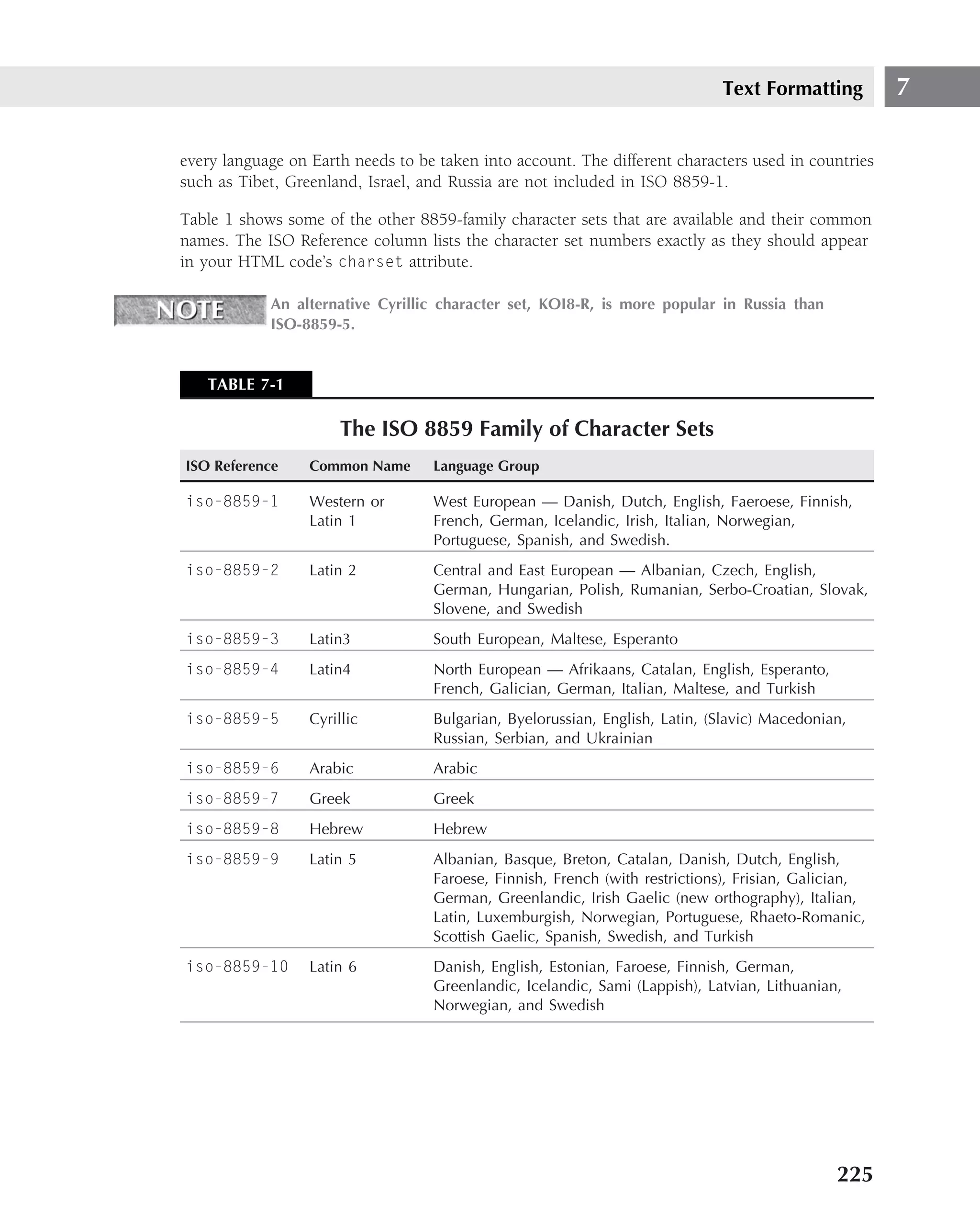

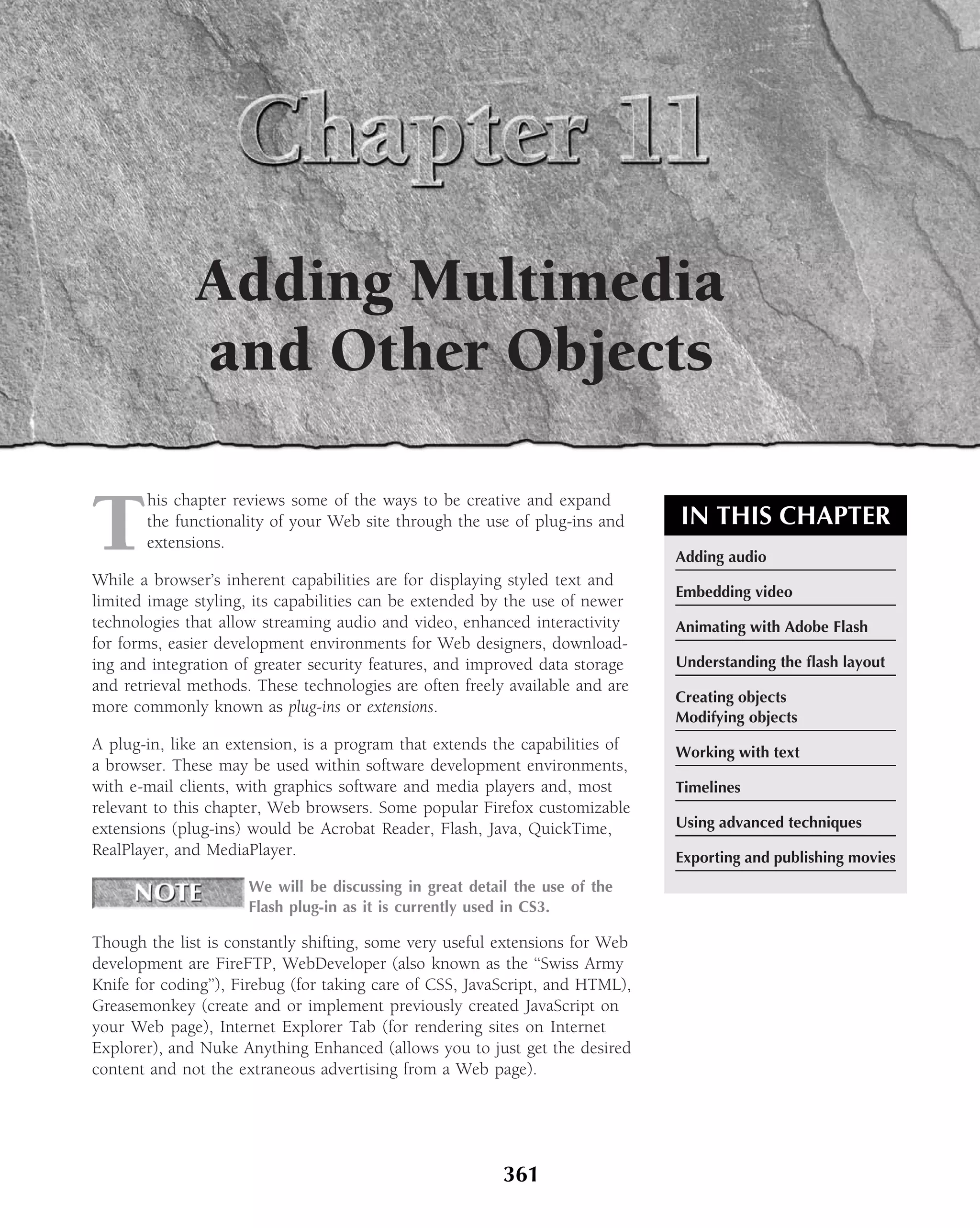

- The book covers topics such as building web pages, popular web design tools, HTML basics, links and navigation, multimedia, CSS, JavaScript, publishing websites, and more.

- It was published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. in 2008.

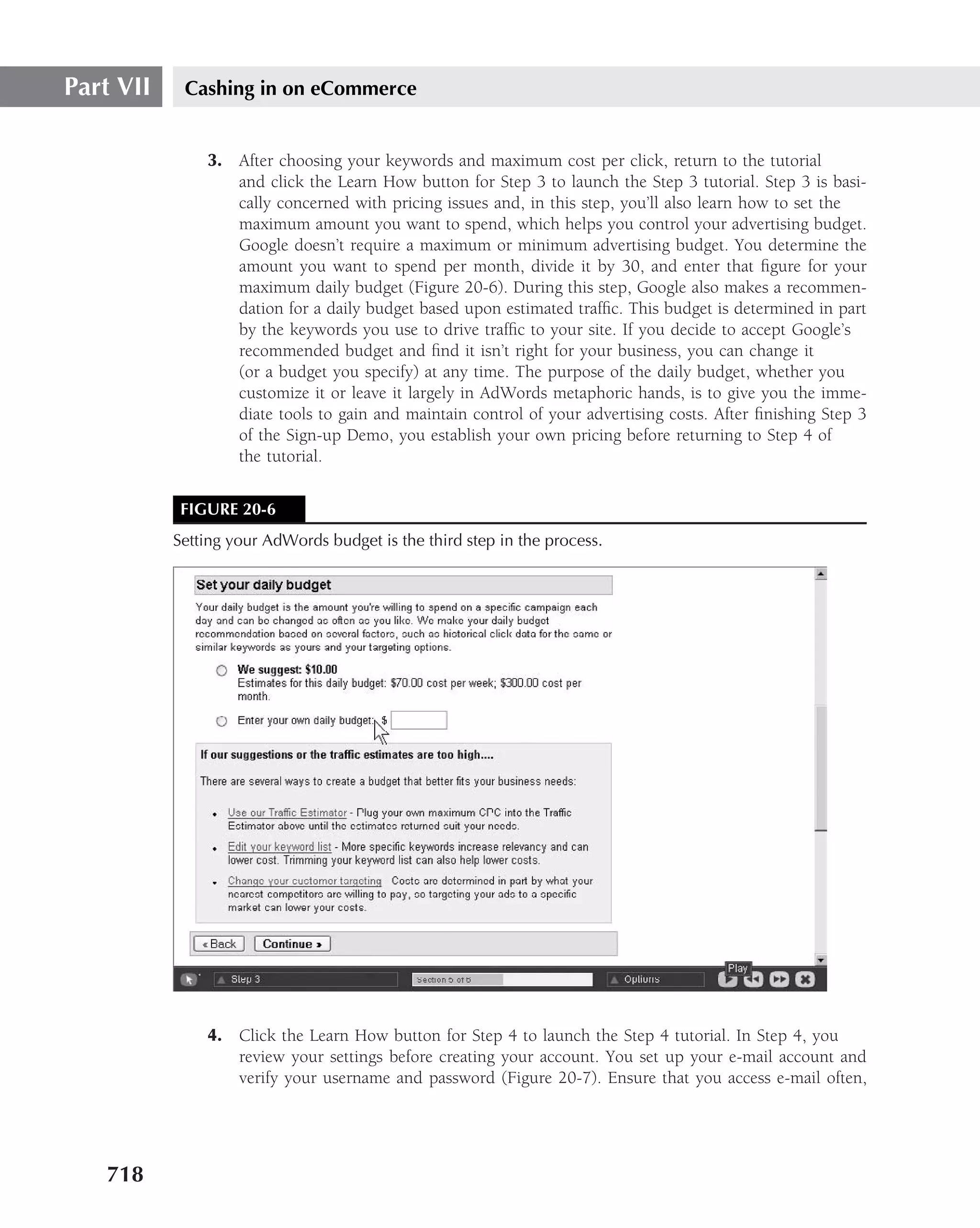

- The authors thank various individuals and organizations who contributed to and supported the creation of the book.

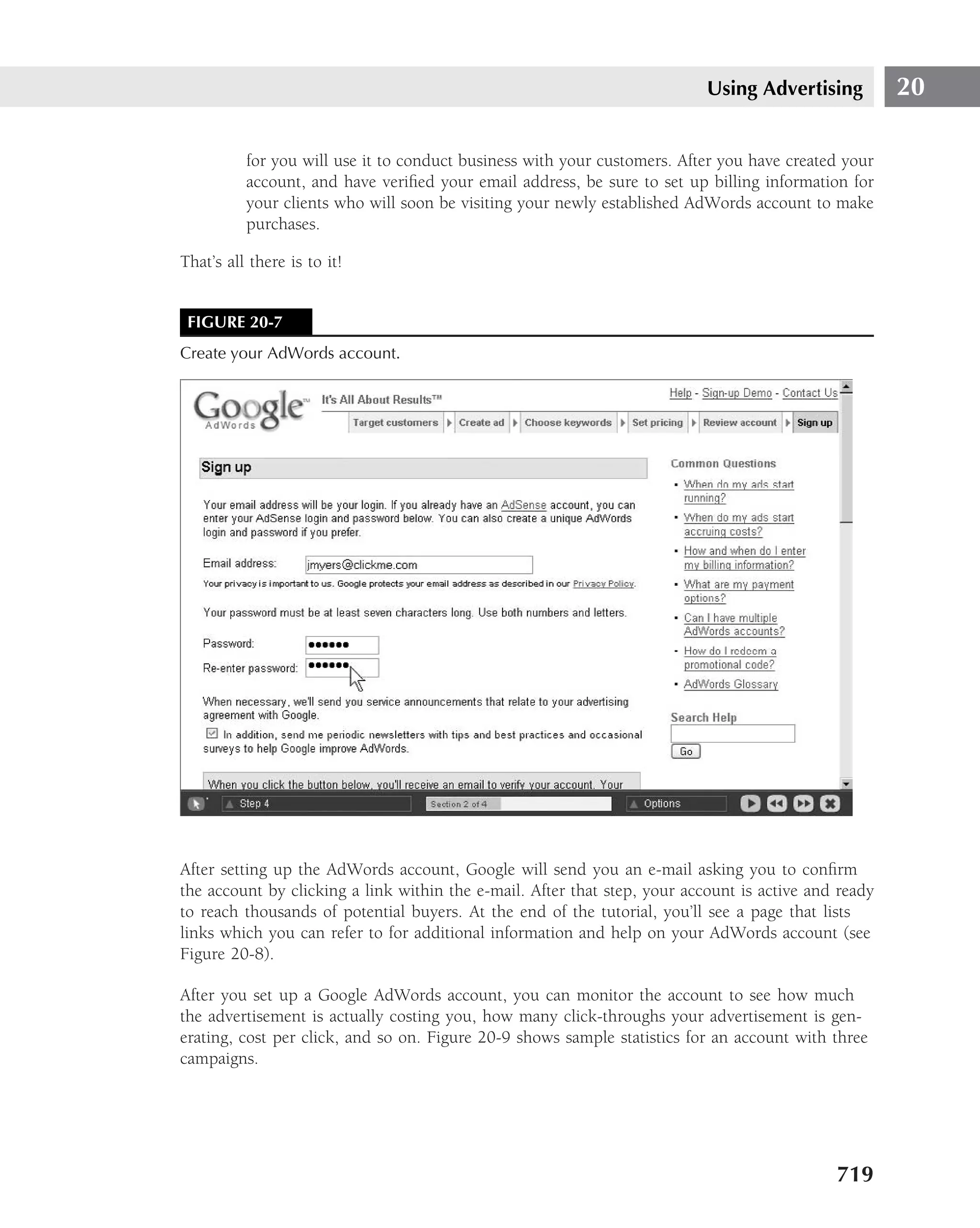

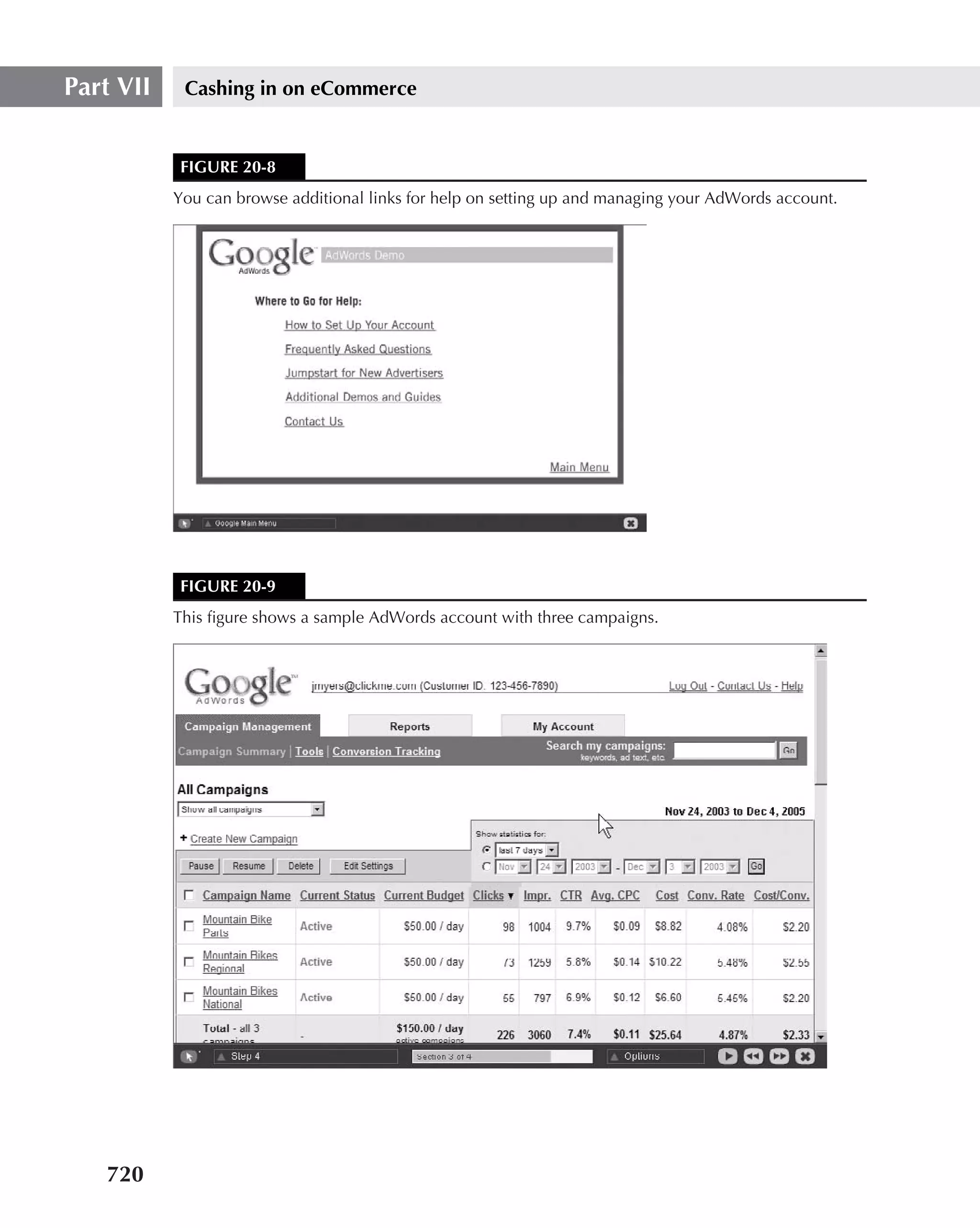

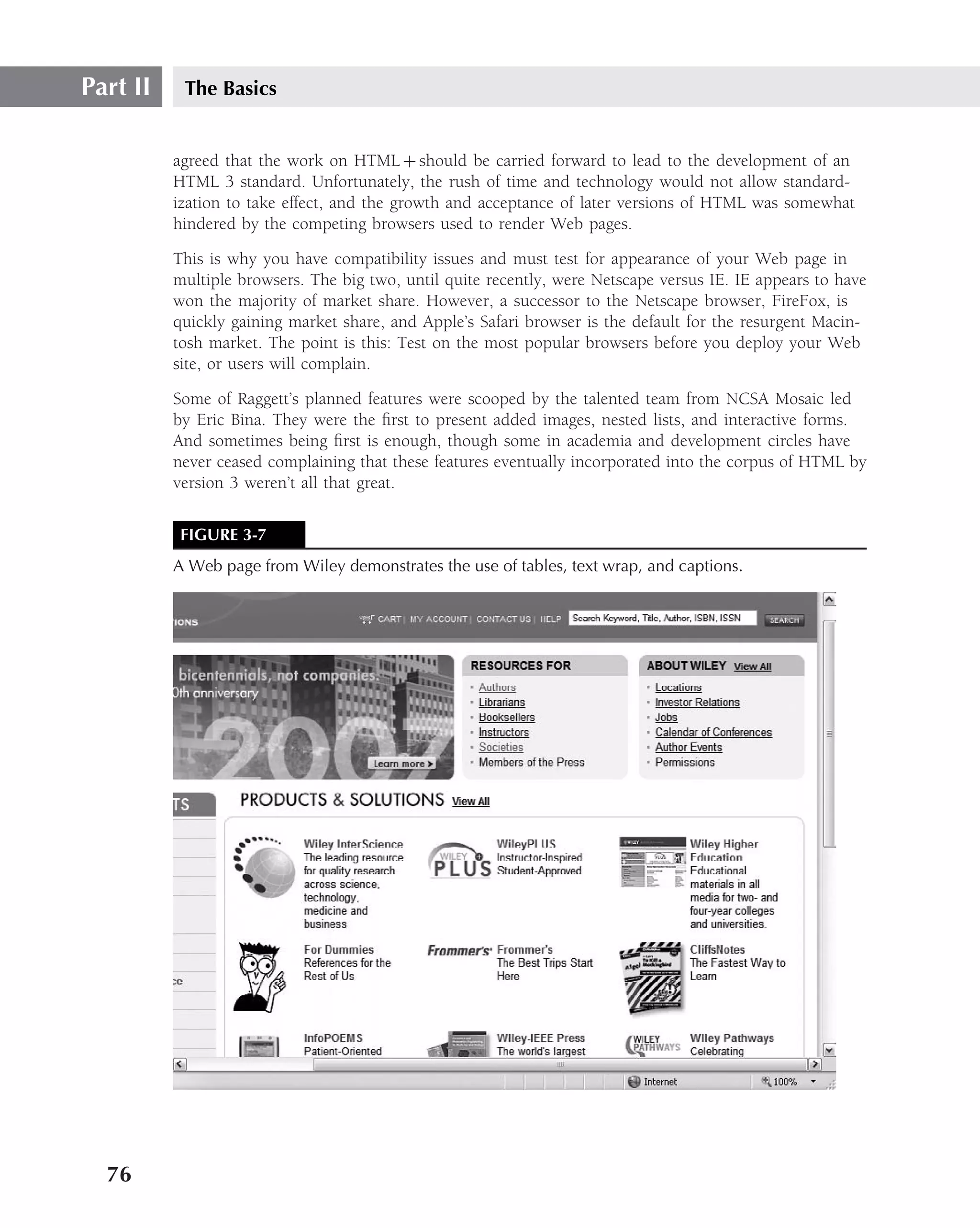

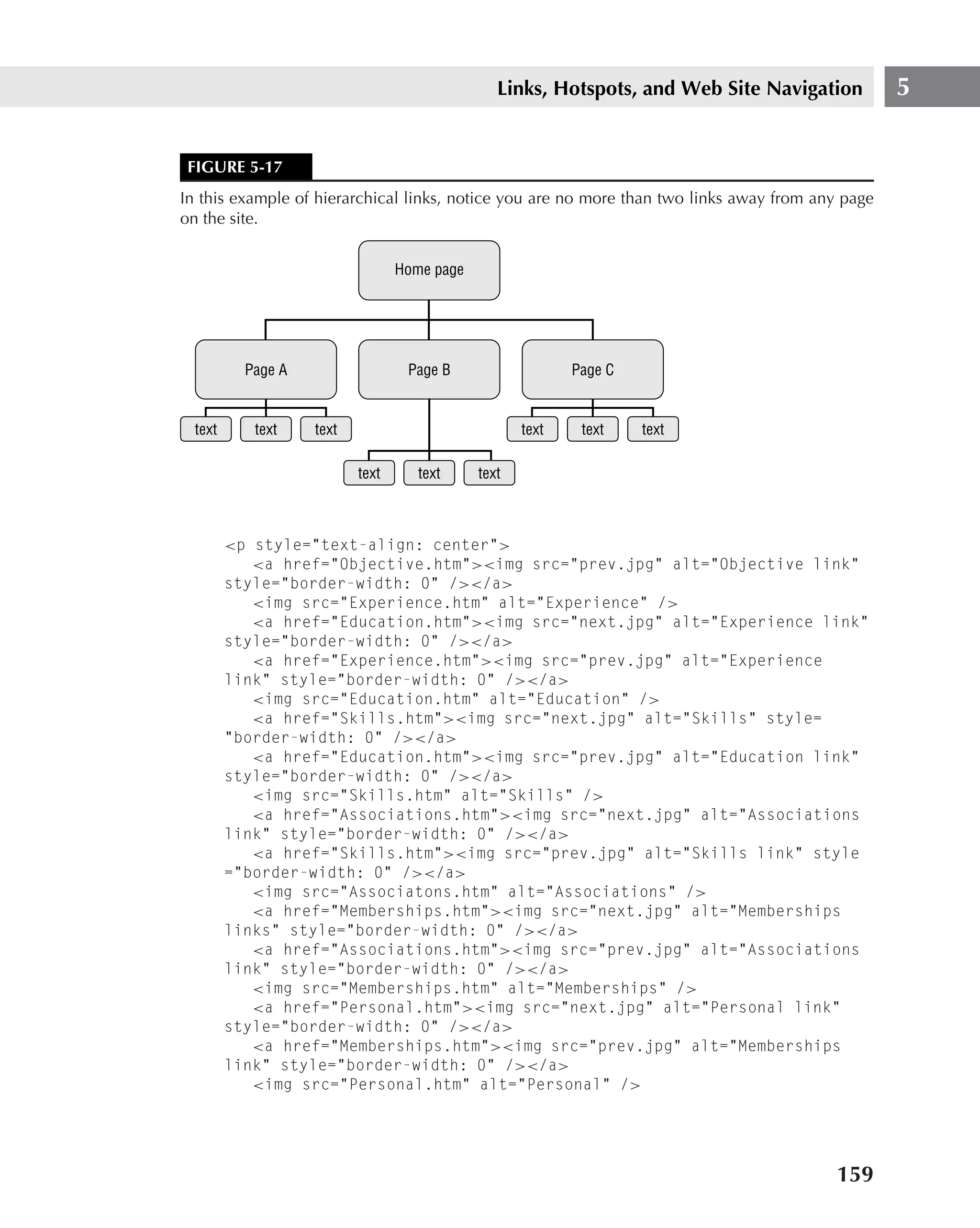

![Part II The Basics

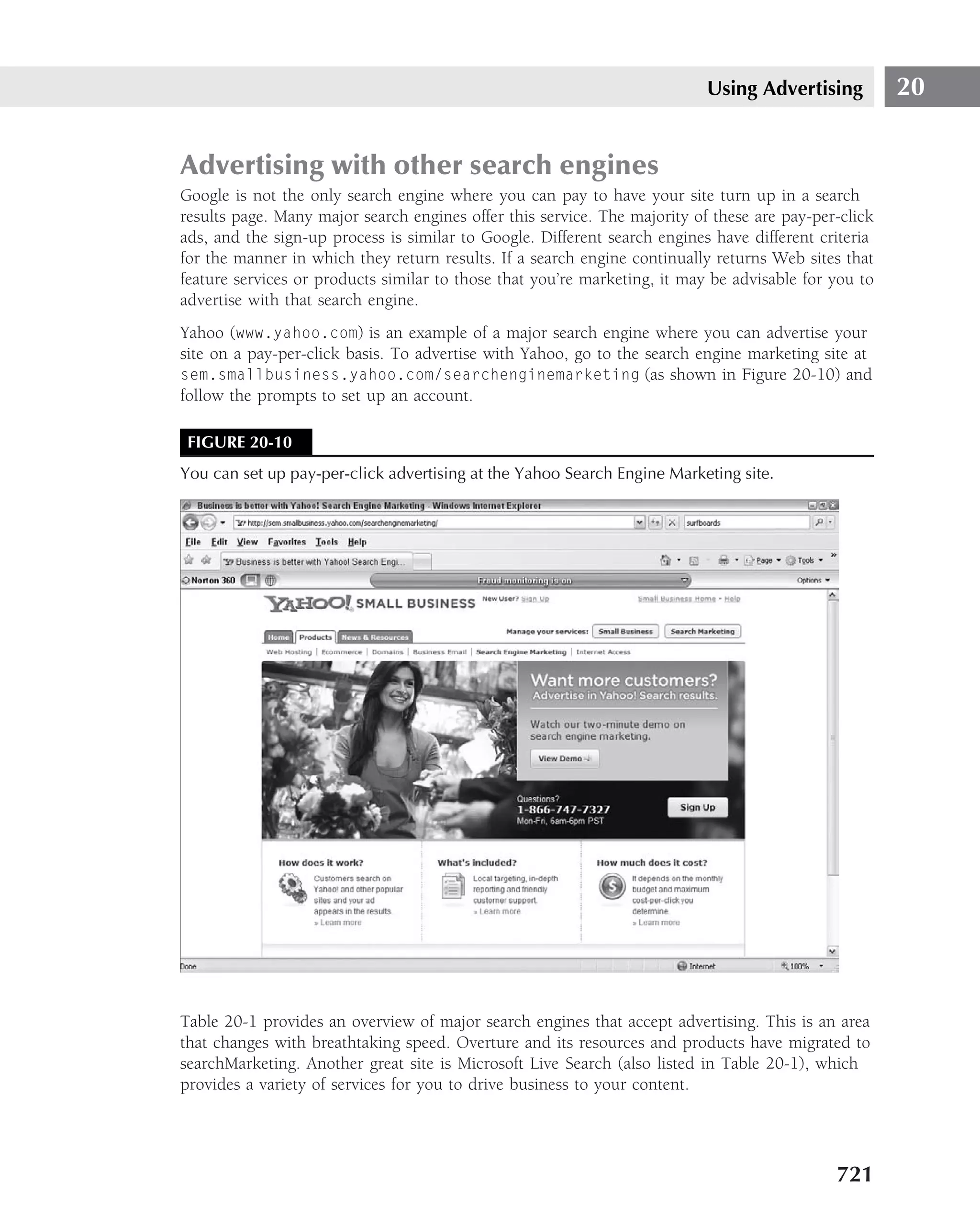

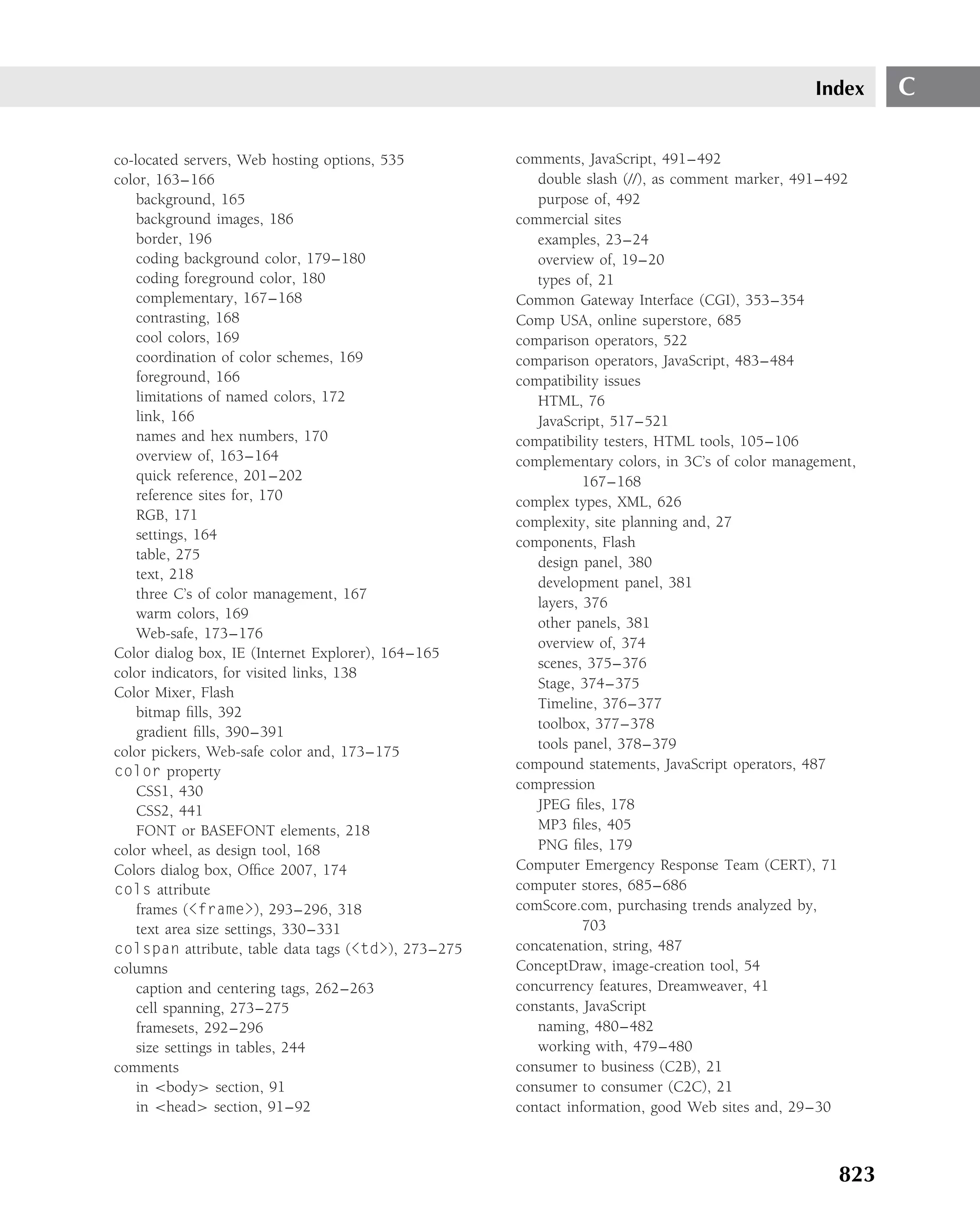

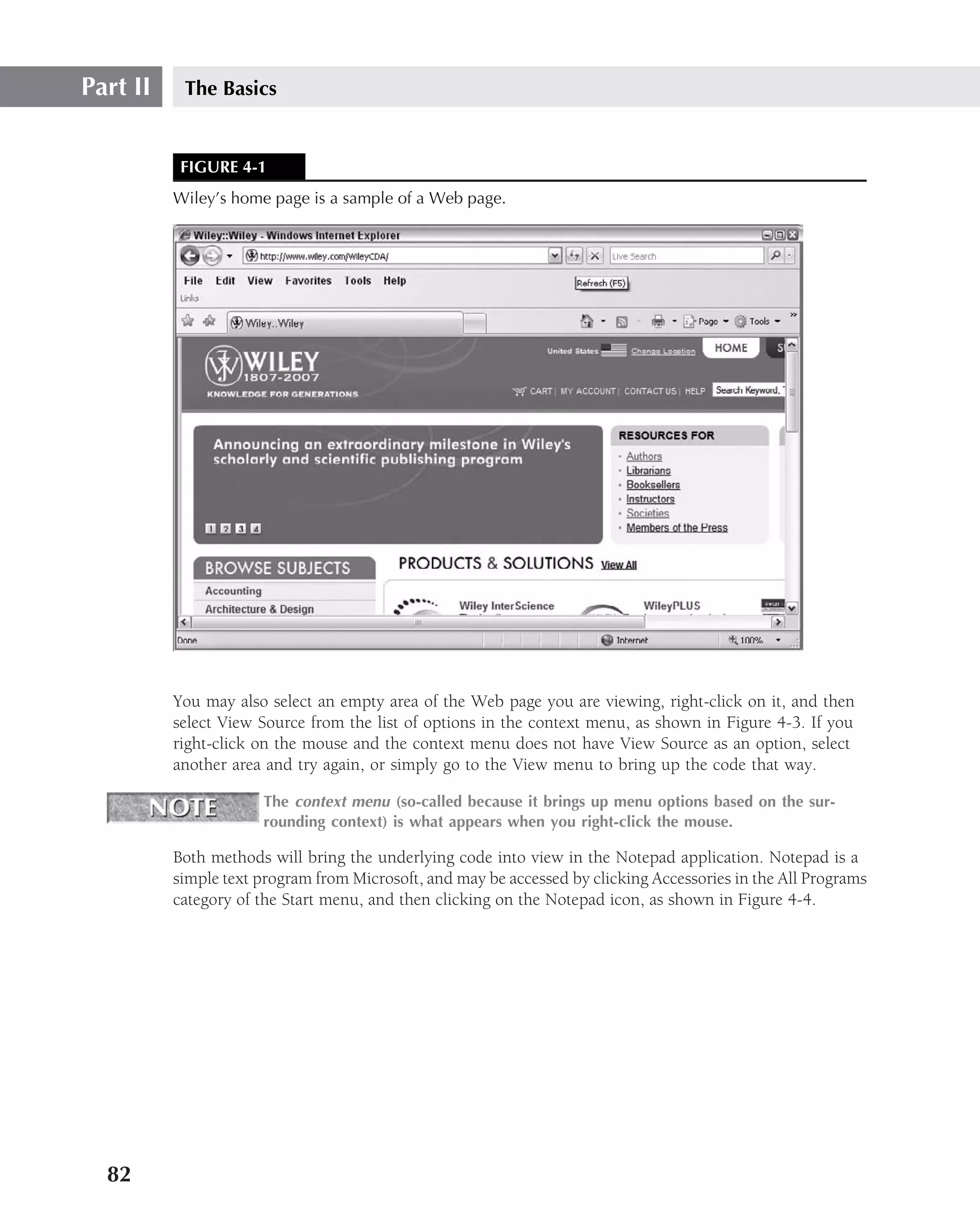

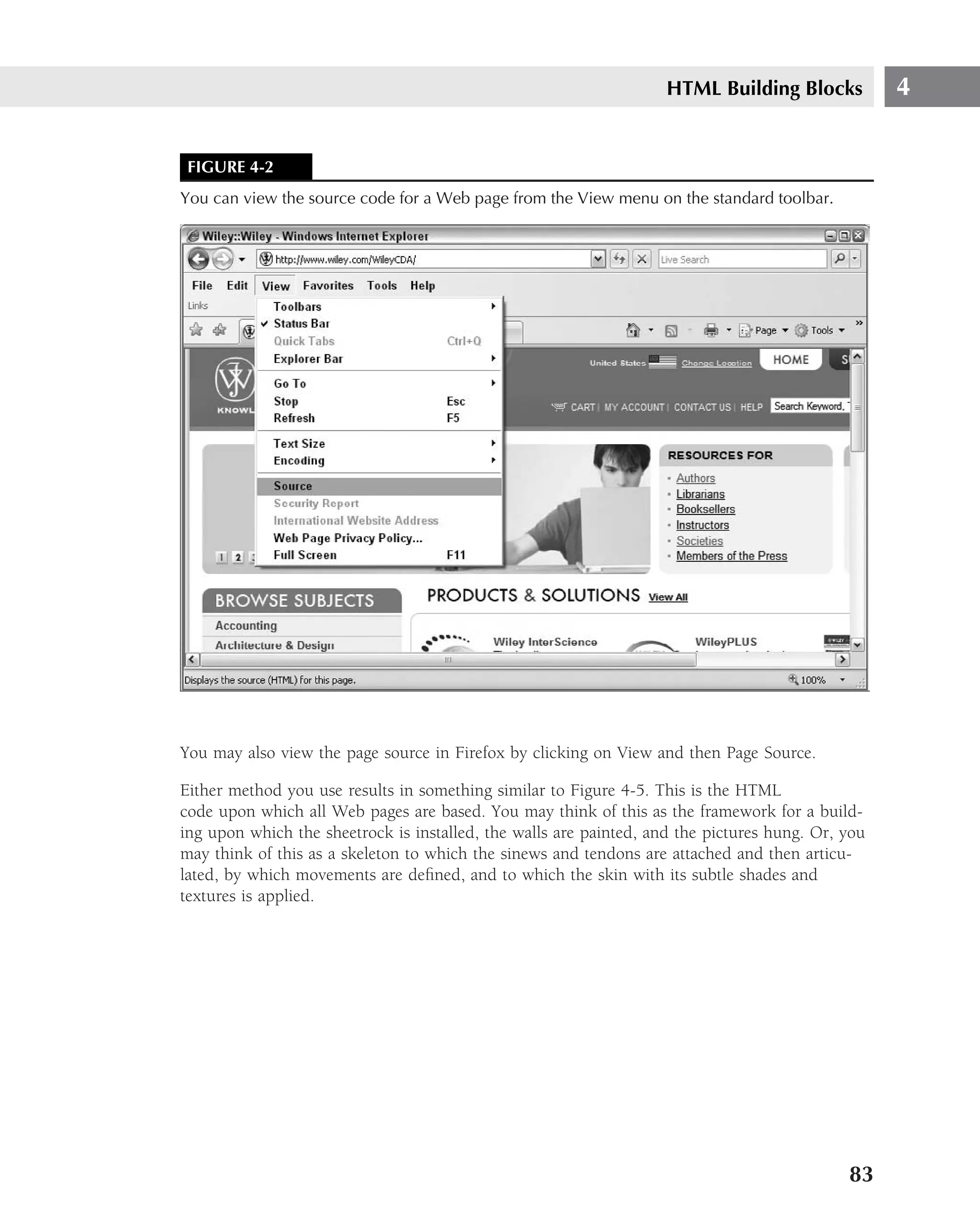

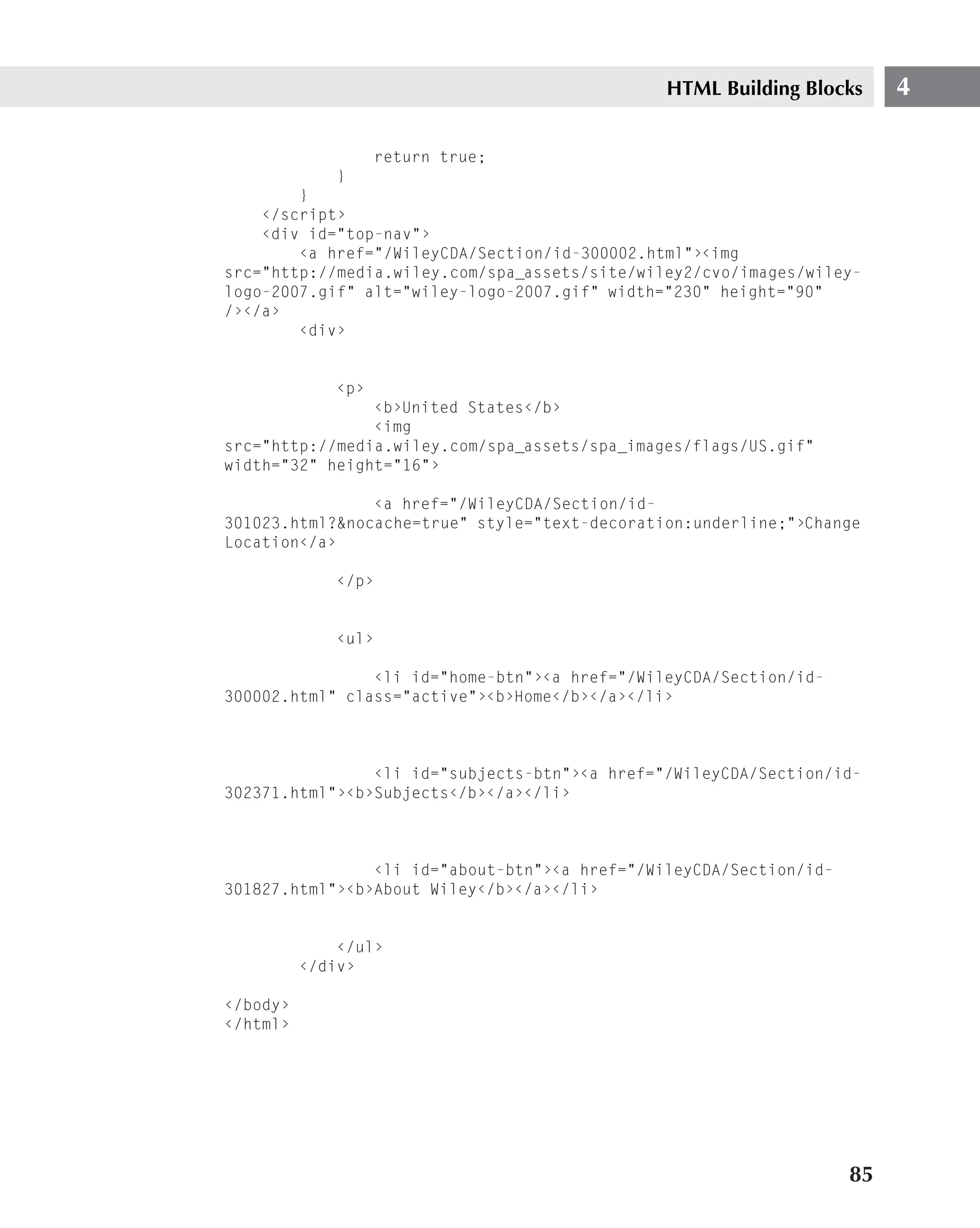

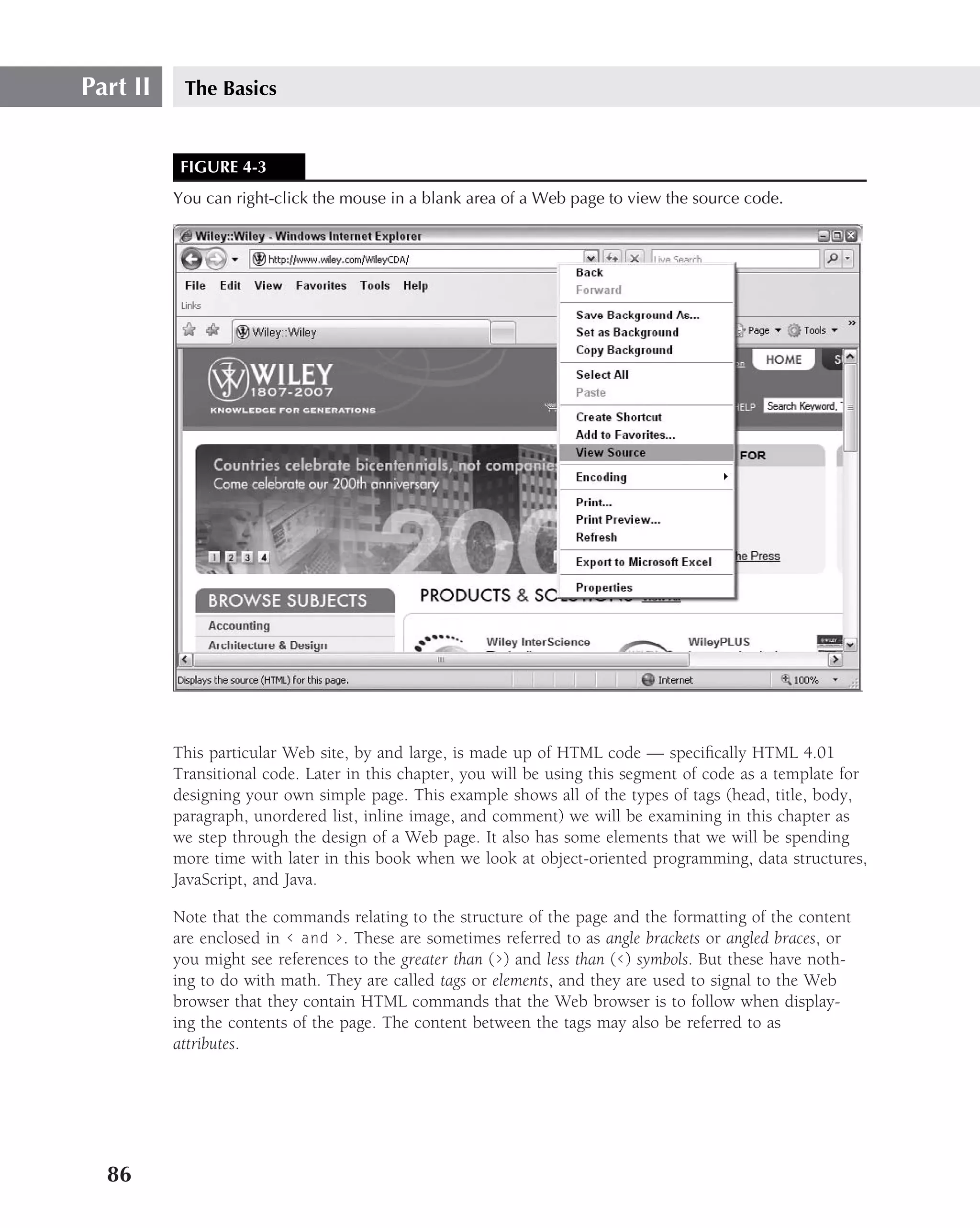

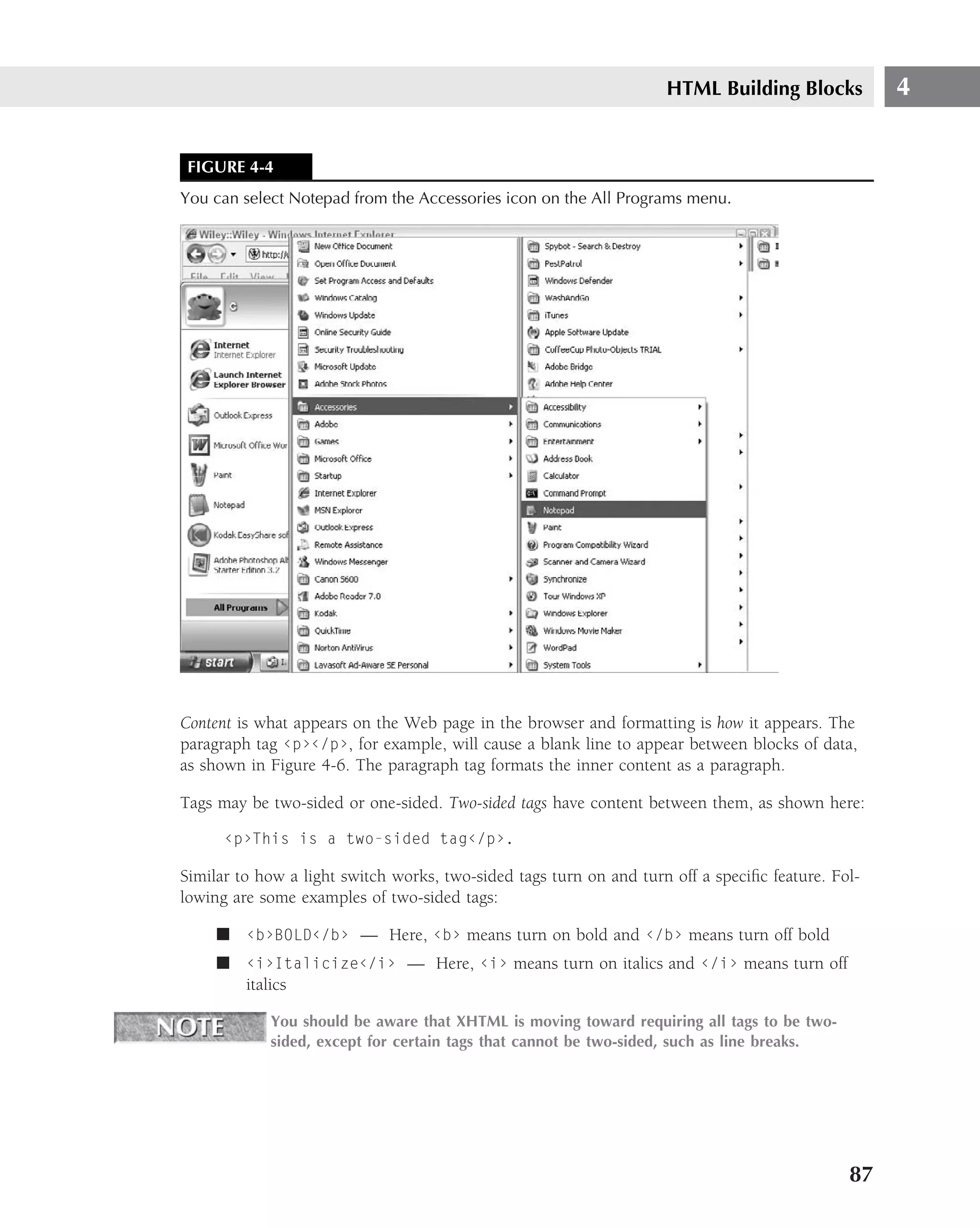

In the example Web site shown in Figure 4-5, the following is the complete underlying code

that is used to render the page:

DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd"›

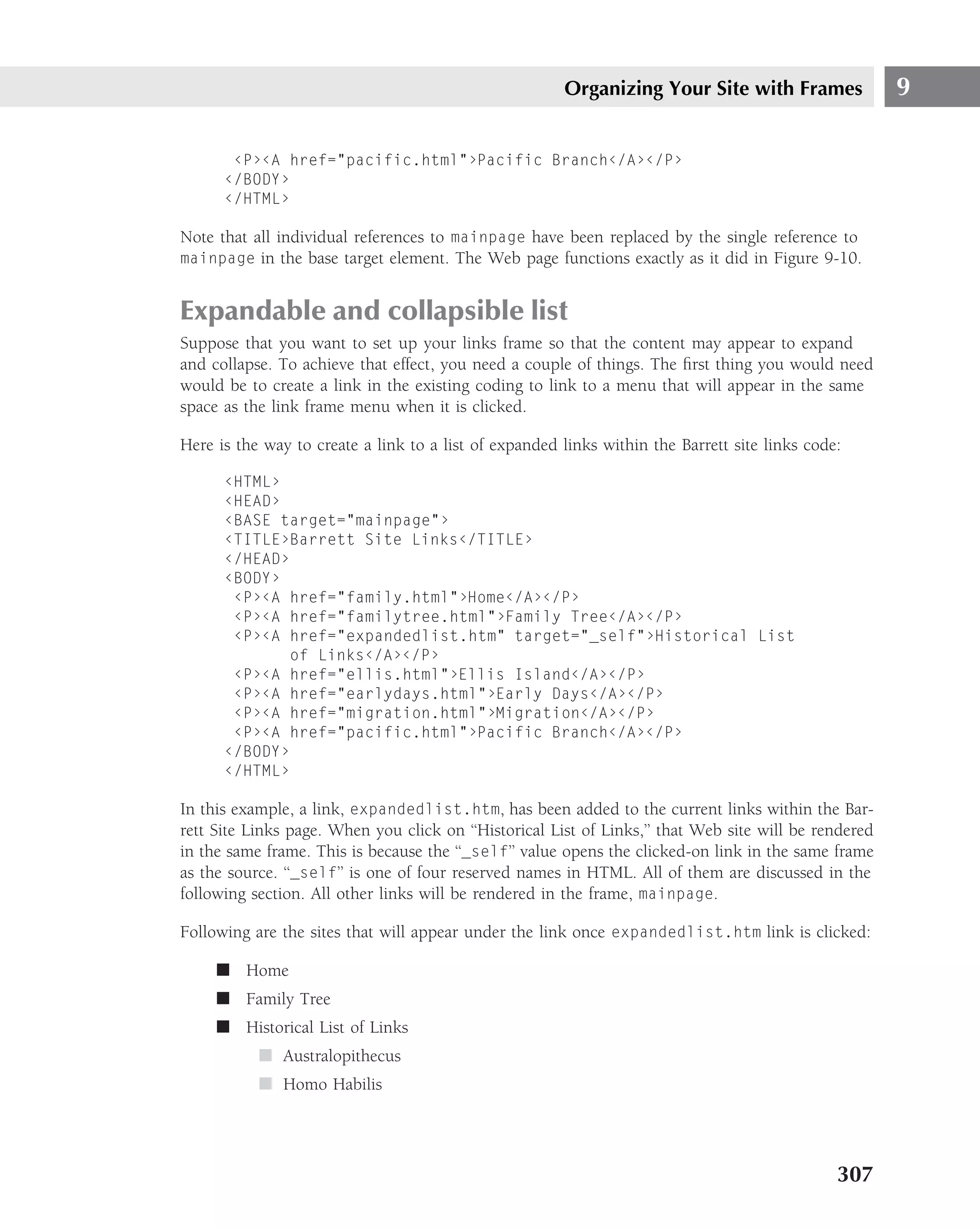

‹!-- Build: R12B015 --›

‹!-- Strand Id: 0114864306 --›

‹!-- layout( Wiley Homepage ) --›

‹html›

‹head›

‹link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style.css"

type="text/css"rel="stylesheet"›

‹title›

Wiley::Wiley

‹/title›

‹script language="javascript" src="/WileyCDA/site/shared/

form_validation.js" type="text/javascript"›

‹/script›

‹!--[if lt IE 7]›

‹link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style-ie.css"

rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"›

‹![endif]--›

‹/head›

‹body›

‹div id="page"›

‹!-- dynamicFeature ( ref:SITE_SPECIFIC_NAV ) --›

‹!-- BEGIN HEADER --›

‹script language="JavaScript"›

function do_check (form) {

if (form.query.value=="") {

alert(’Please make an entry in the product search

field.’);

return false;

} else {

84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-120-2048.jpg)

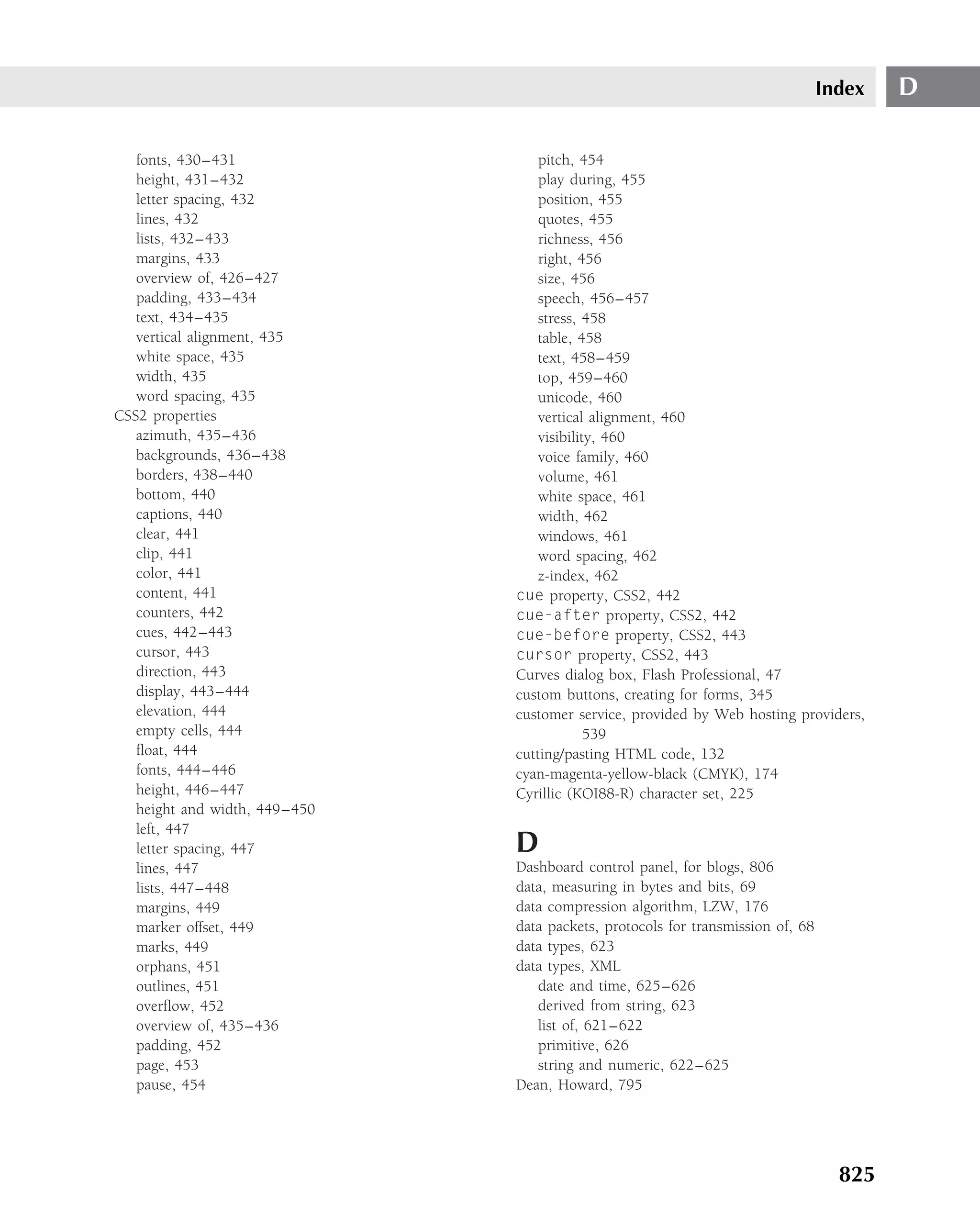

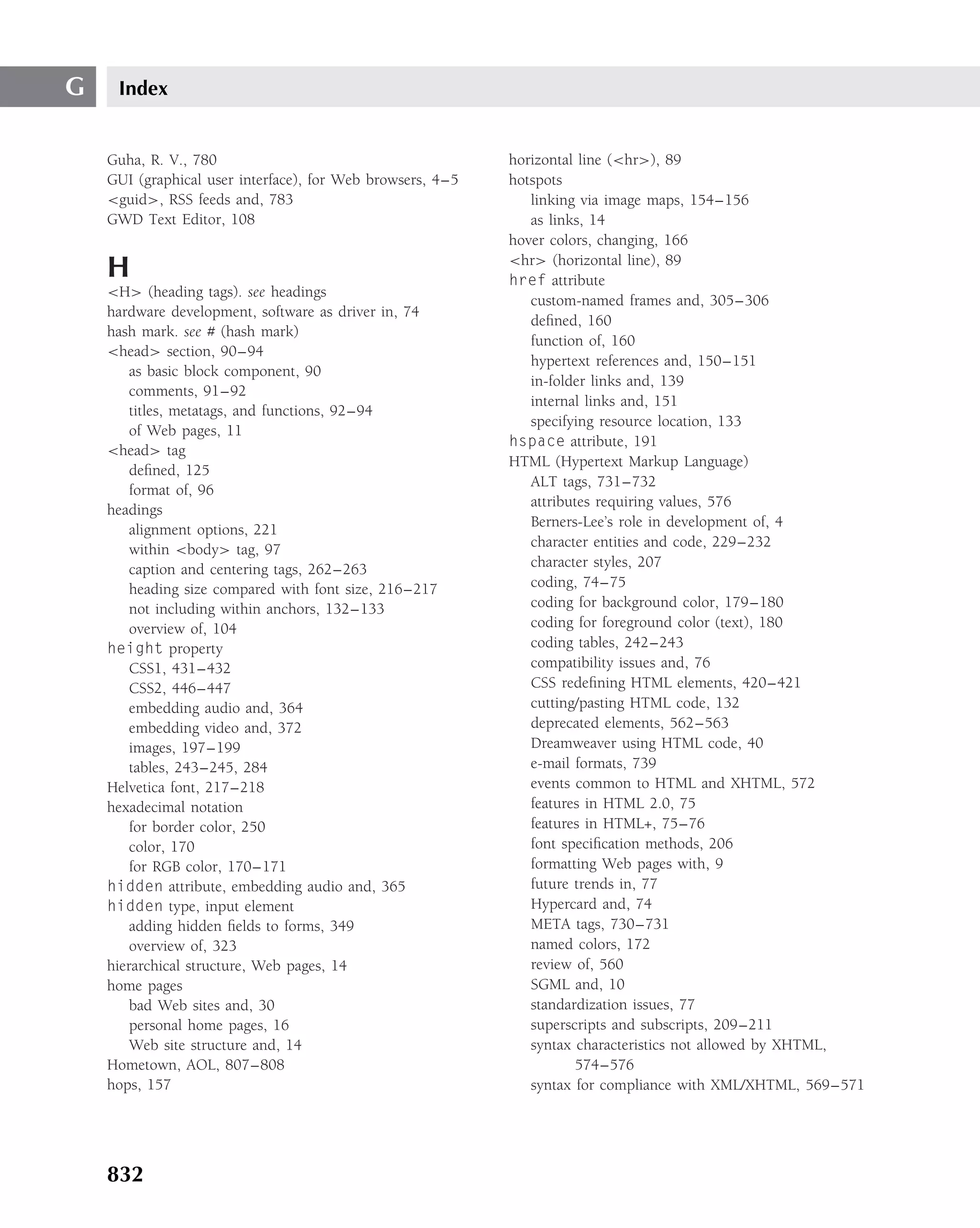

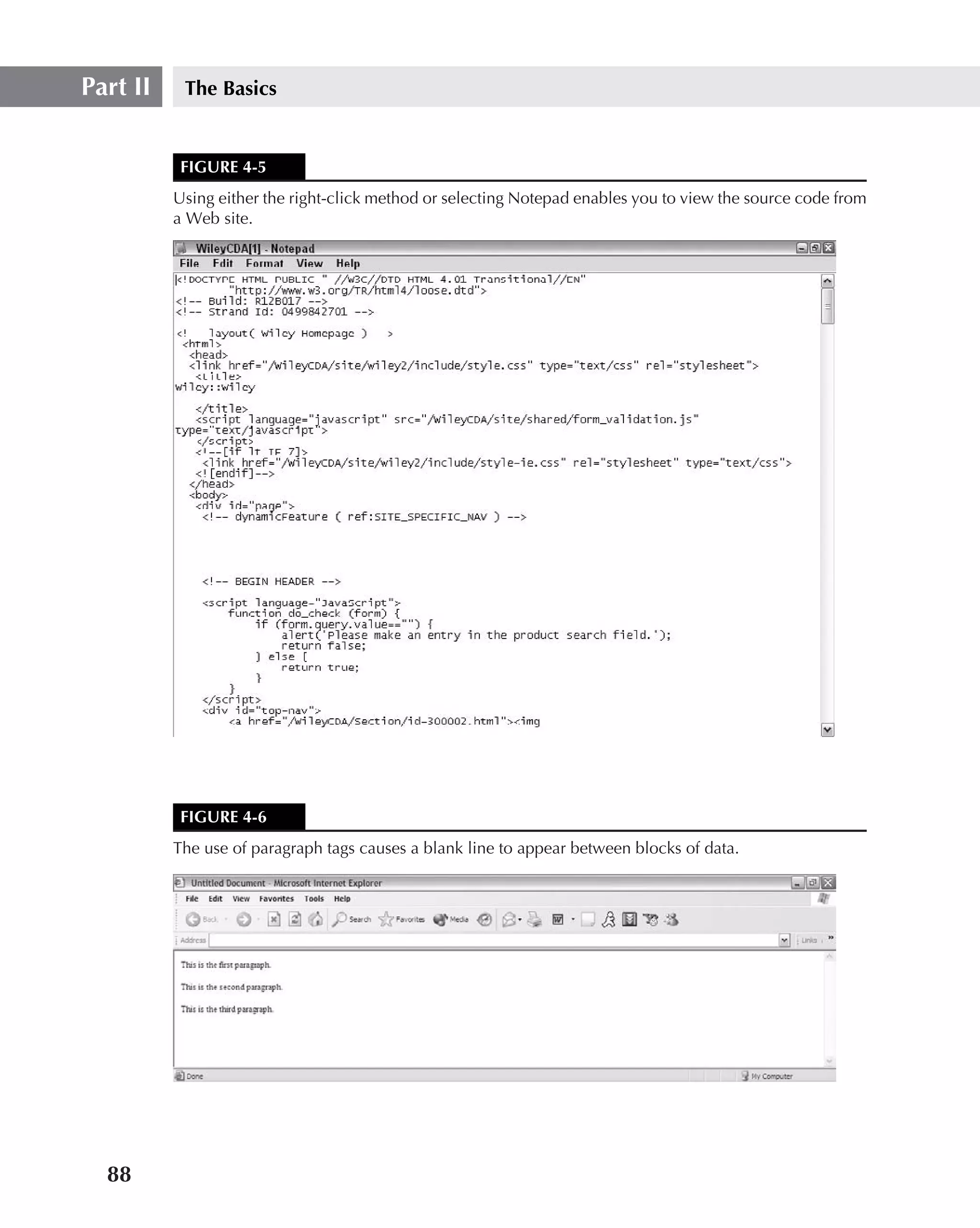

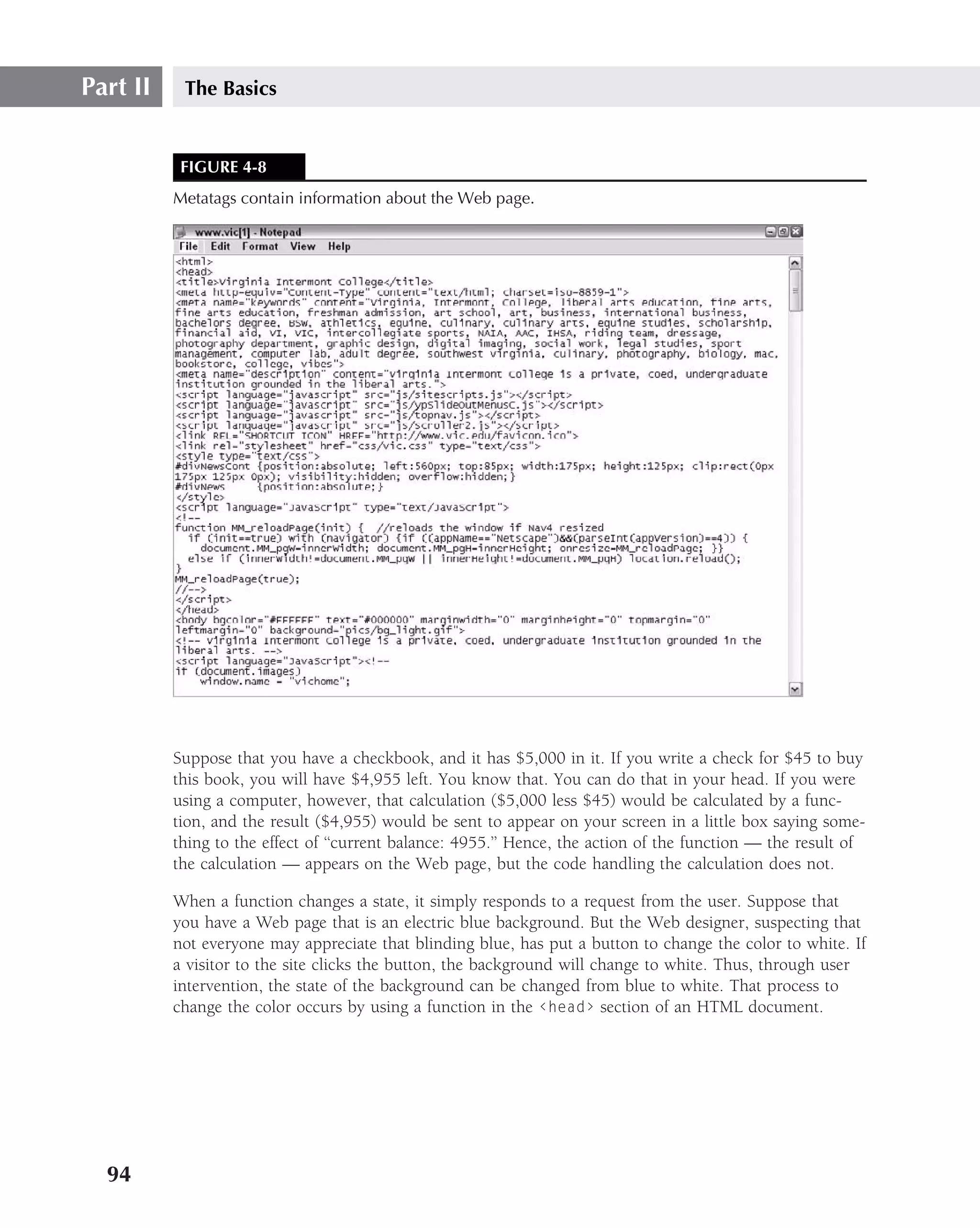

![HTML Building Blocks 4

<head> section

Within the ‹head› tags are the nonprintable elements of the Web page. These would be the

description of the Web page, including statement of purpose, date, last created/modified ver-

sion, programmer information set off by comment tags, and any associated meta tags (metadata).

Comment tags are set off by using the following format:

‹!-- This is where you make a comment --›

Comments

Comments may be multi-line and only cease when the end tag --› is inserted. The program

does not read or interpret comments as executable code. It simply skips over the commented

lines. Here is an example of a comment section giving info about the program and

programmer:

‹!--This web page was constructed by John Q. Programmer on July 4,

2007. Its purpose is to demonstrate the use of the following

common tags: ‹hr›, ‹p›, ‹ol›, ‹ul›, ‹li›, ‹address› --›

Here is a section of actual comment code from the head of the example Web site (Figure 4-1):

‹!--[if lt IE 7]›

‹link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style-ie.css"

rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"›

‹!--[endif]--›

What this says in English is that if this Web browser trying to access the site is less than IE 7.0,

then link it to the Internet Explorer styles page located at the address listed in the href. That’s

all (endif).

Comments may also appear in the ‹body› block of the document where they would be used to

briefly explain the purpose of a subsection of the program (such as a subroutine, subprogram,

submodule, and so on). Comments may also explain the next iteration or the setting of flags for

a decision structure, or explain the values of a multivalued variable in a case structure. The fol-

lowing is an illustration of a comment regarding a function call:

‹!--This case structure is to allow users to input which direction

they want to move player on a map --›

‹script›

/* This is a JavaScript function and the commented section uses this

comments tag */

switch(direction)

{

case ’n’:

go_north();

91](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-127-2048.jpg)

![Part II The Basics

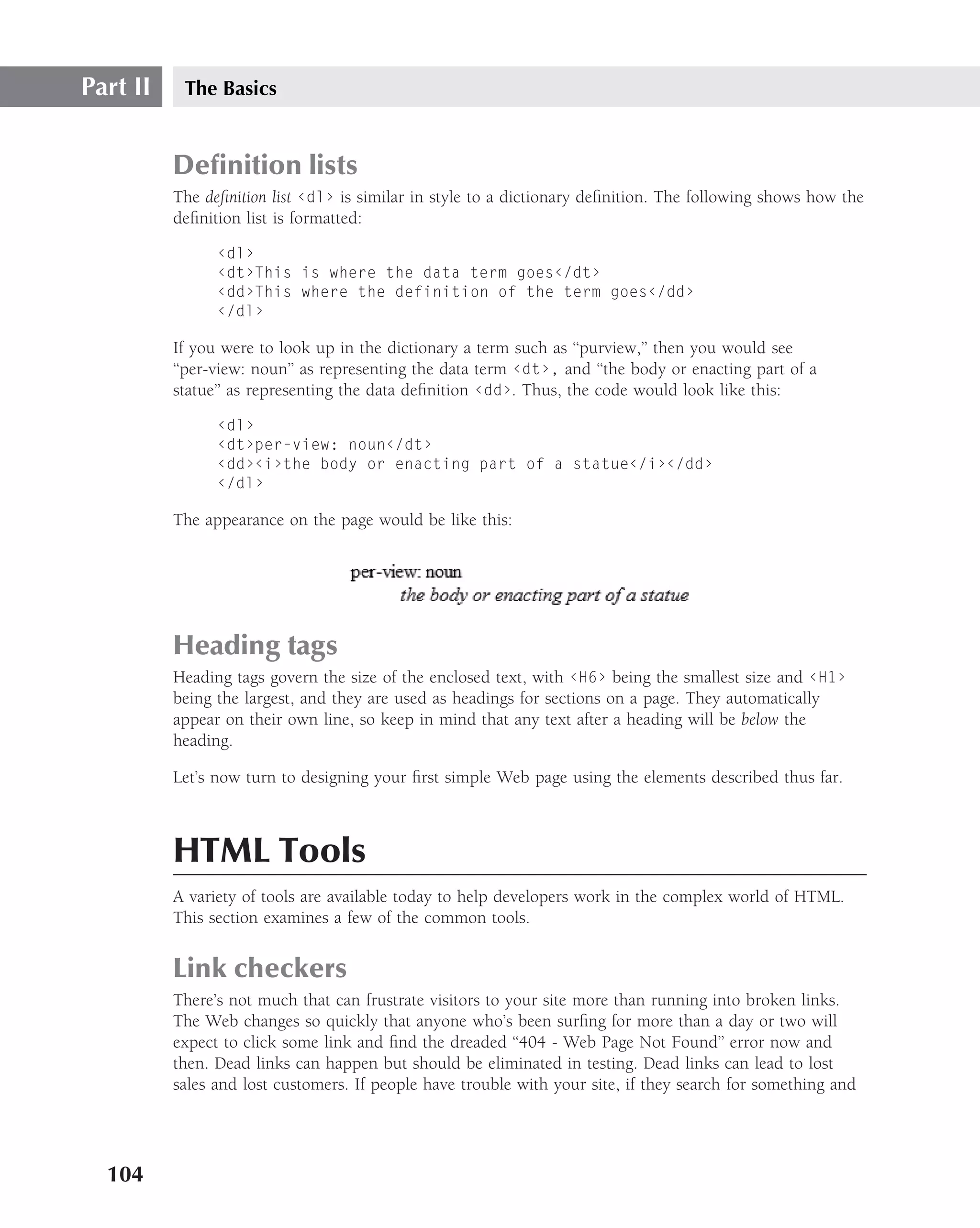

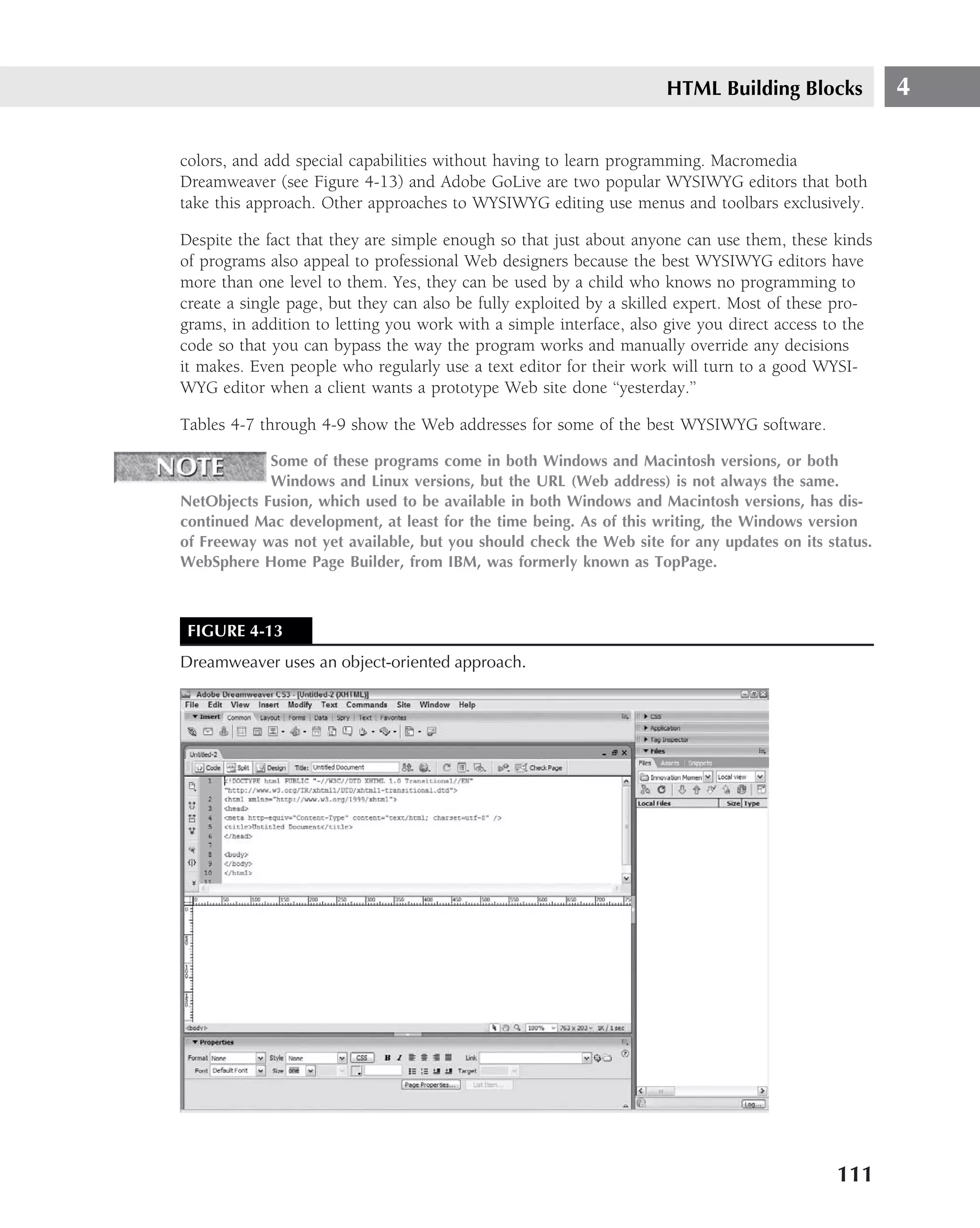

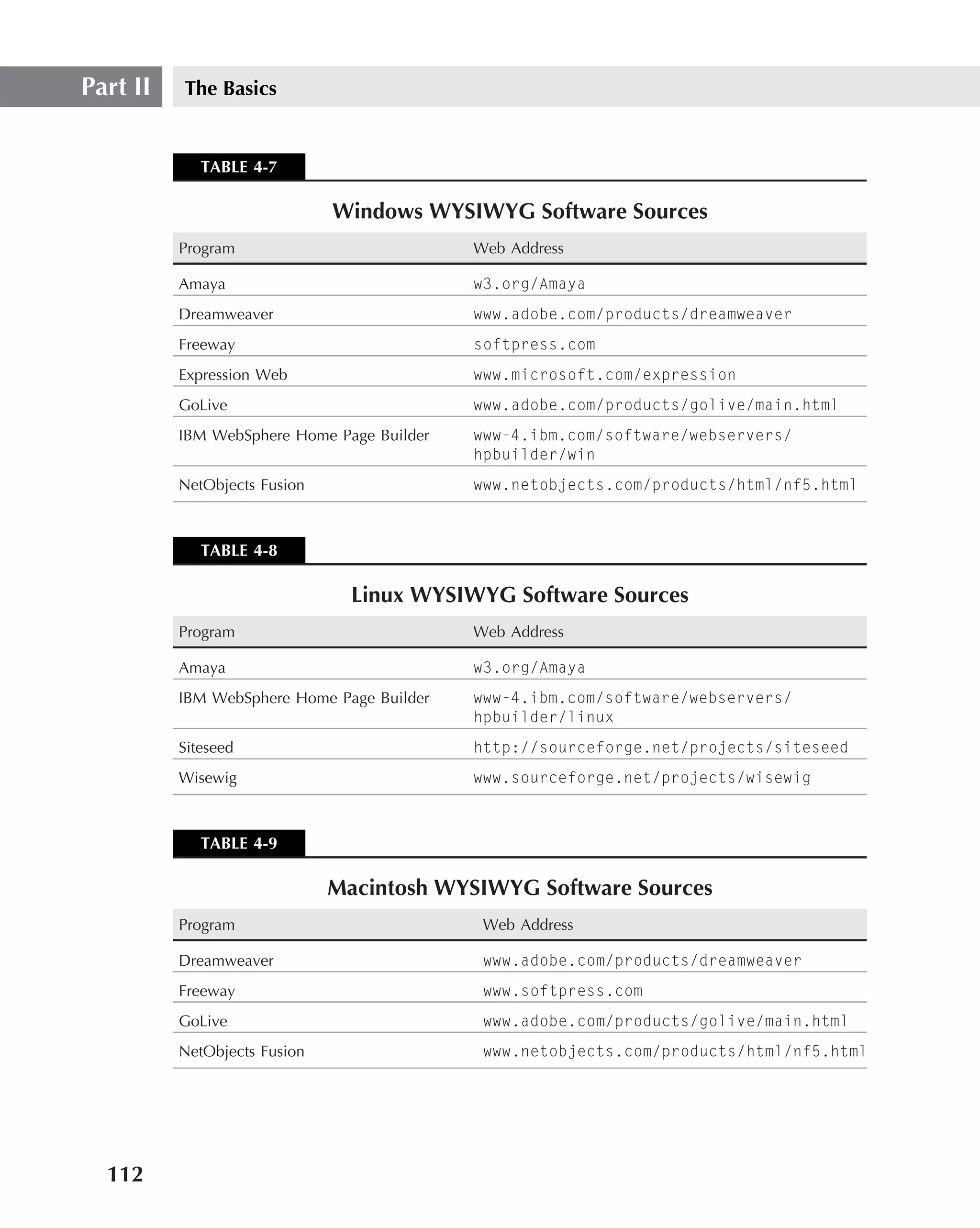

Word code gives HTML validator programs fits. However, most Web browsers perform a great

deal of error checking and correction, so using Word to create Web pages is not a totally

impossible option. If you want to work in a WYSIWYG environment on the Windows operating

system and you have Word, you might as well give it a try before you buy a serious Web page

creation program, but we’d advise against using it to do anything significant or important.

Be sure to always test any Web project you do with more than one company’s Web

browser. If possible, test with different versions of the same browser, too, and view

the page on as many platforms as you can. If you’re using Windows, for example, and don’t have

a Linux box or a Mac, ask a friend to surf to your pages and report on them. If you don’t know

anyone who has a different system, try asking for help on the alt.www.webmaster Usenet news-

group.

Exceptions to the rule

As with practically any ‘‘definitive’’ categorization, there are no doubt exceptions to this one, and

it could easily be argued that there are some unusual Web authoring programs that fall between

the cracks. What should you make of Caligari iSpace software, for example? Although techni-

cally a 3D Web graphics program that’s usually employed in conjunction with a traditional Web

authoring tool such as Dreamweaver, it can be used all by itself to create Web pages complete

with text and an impressive number of bells and whistles.

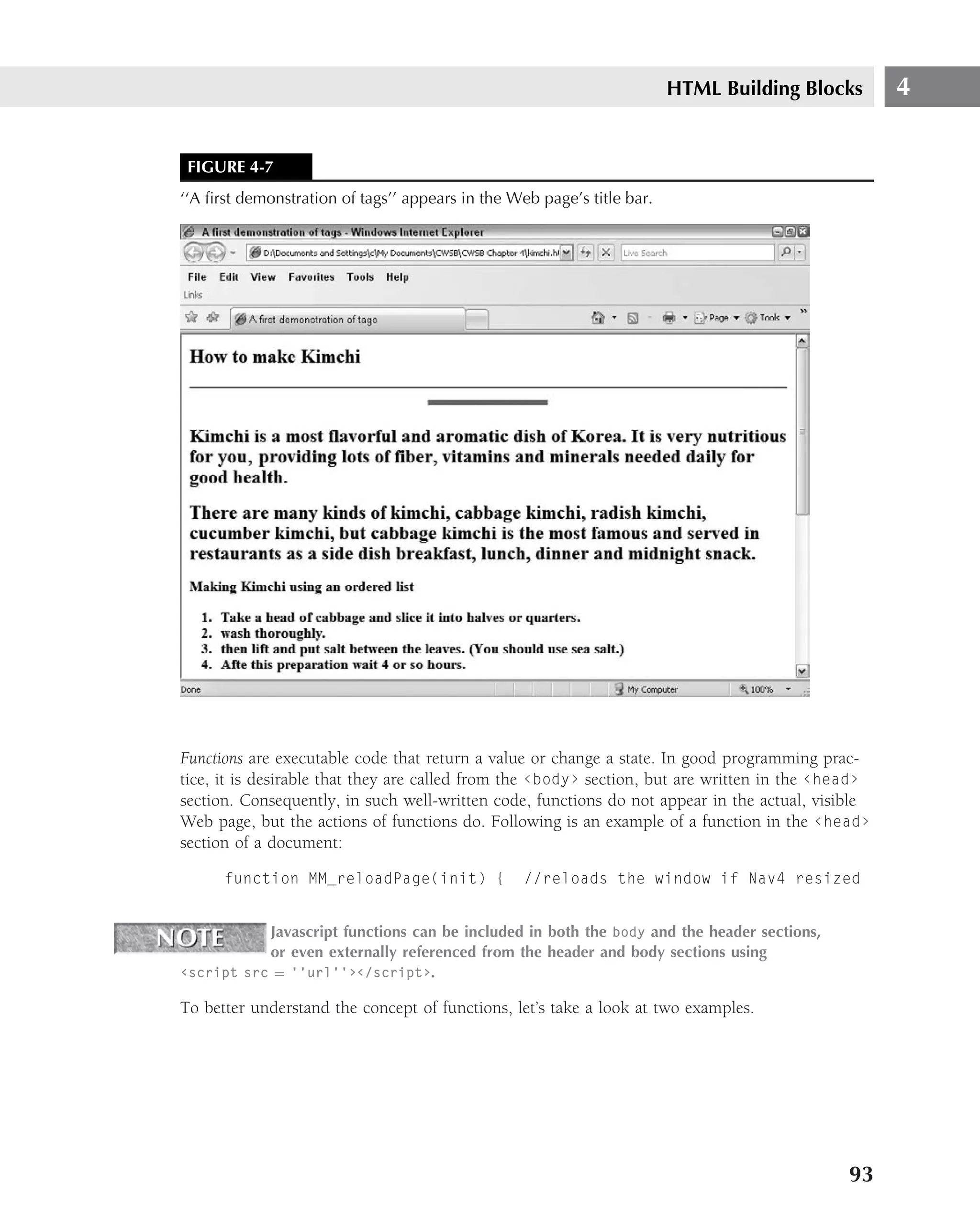

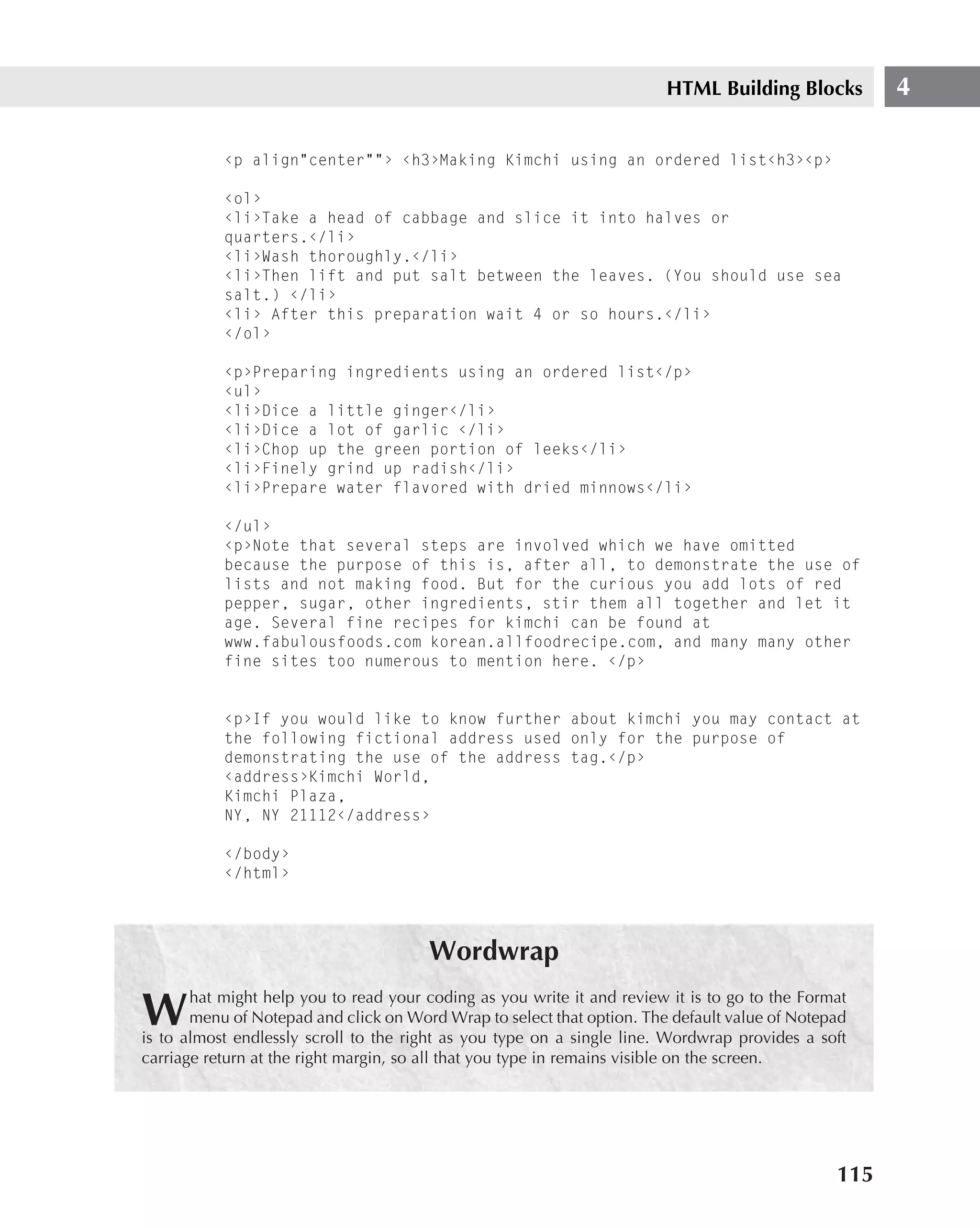

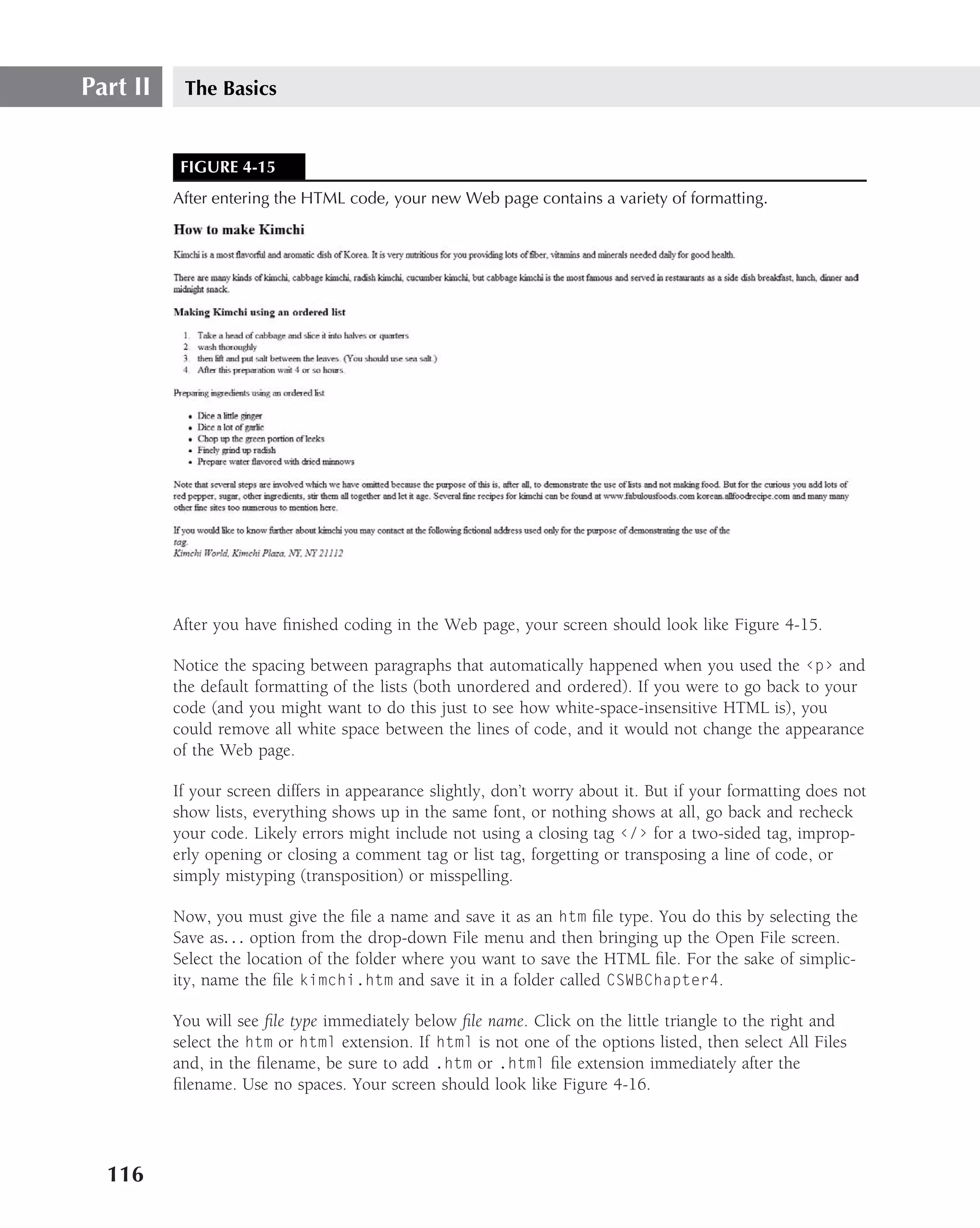

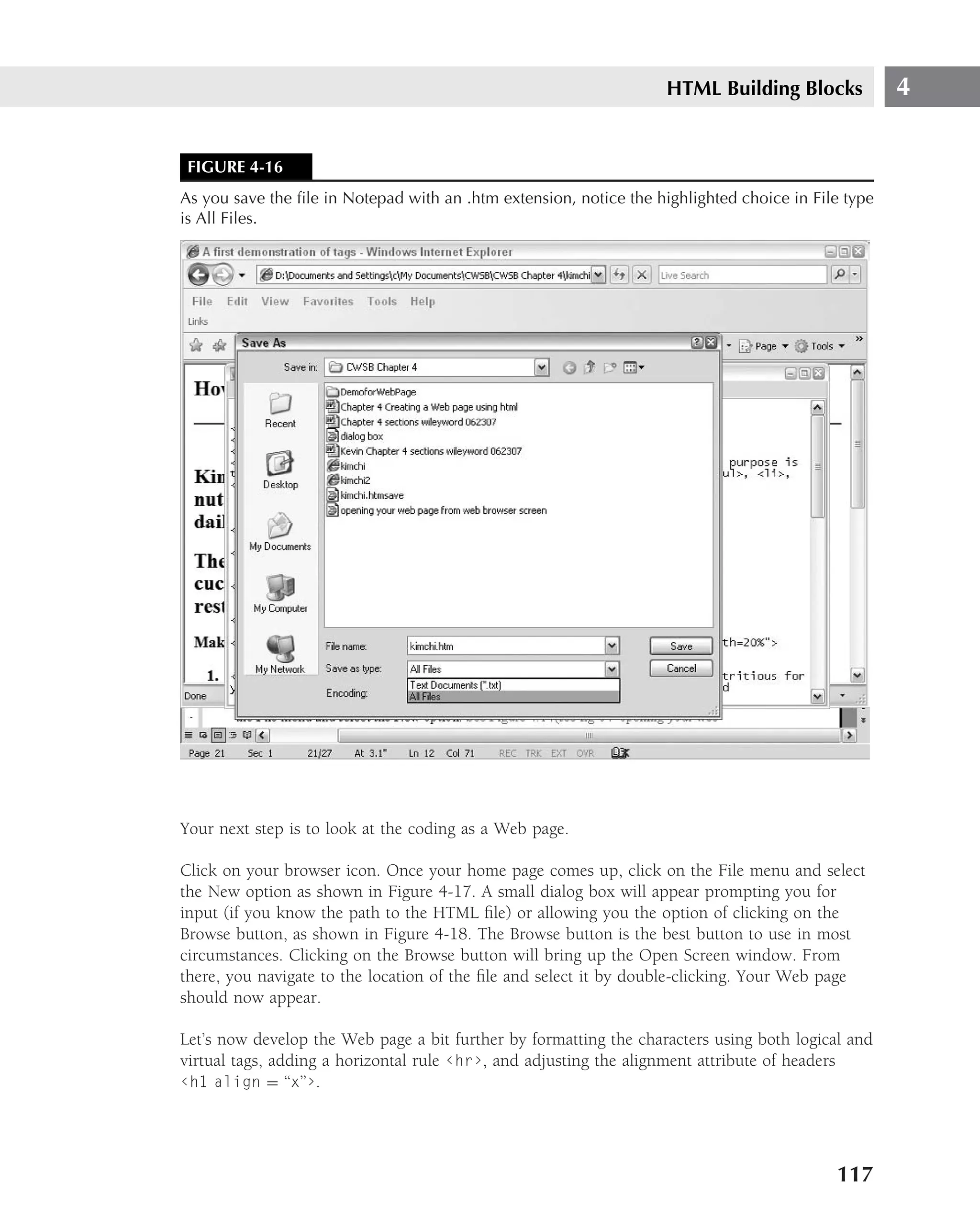

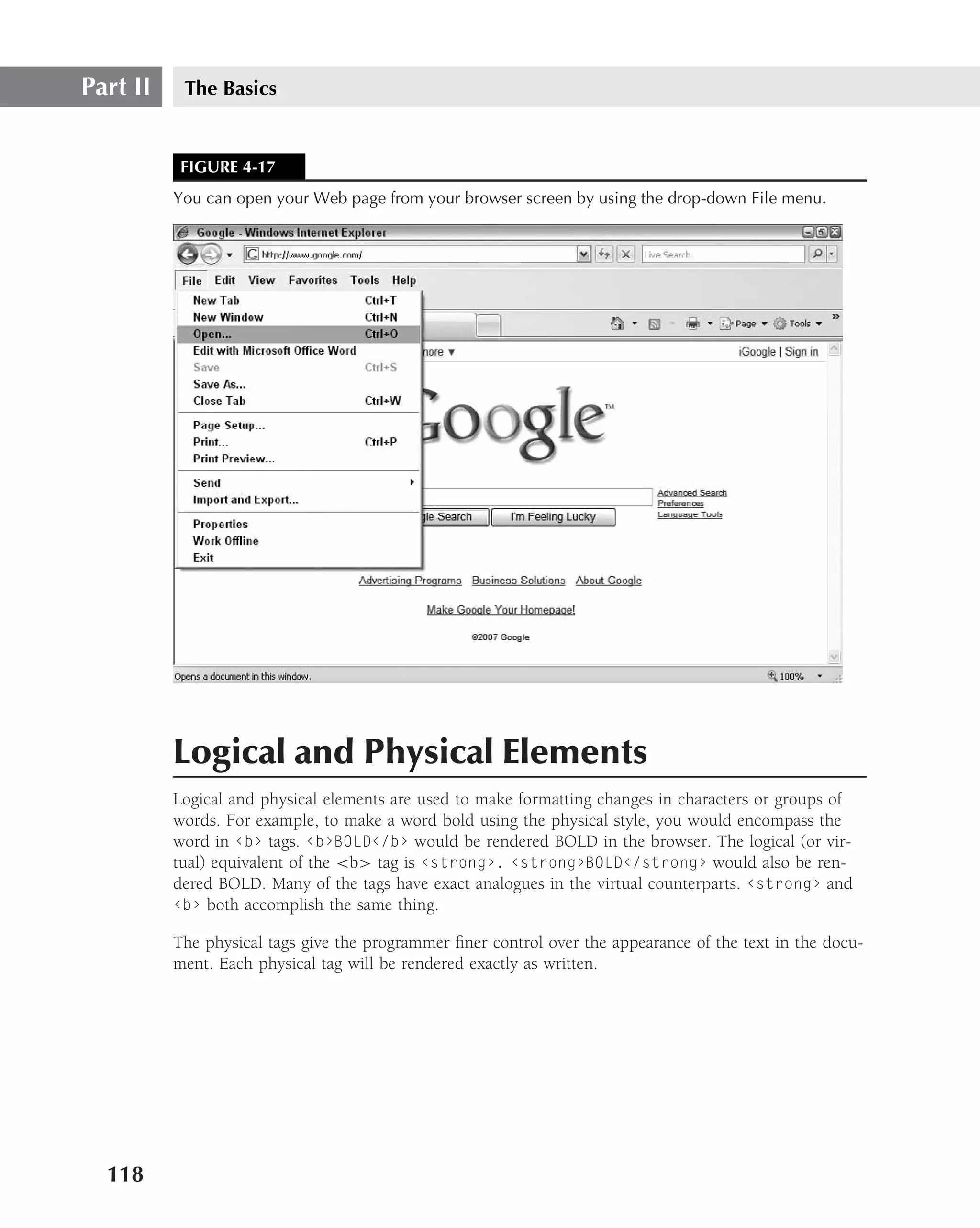

Designing a Simple Web Page

The first thing to do is to click on Notepad, which will present you with a blank document.

Then, type in the following:

‹html›

‹head›

‹title› A first demonstration of tags‹/title›

‹!--This web page was constructed by [your name] on [insert date].

Its purpose is to demonstrate the use of the following common tags:

‹hx›, ‹p›, ‹ol›, ‹ul›, ‹li›, ‹address› --›

‹/head›

‹body›

‹h2›How to make Kimchi‹h2›

‹p›Kimchi is a most flavorful and aromatic dish of Korea. It is very

nutritious for you providing lots of fiber, vitamins and minerals

needed daily for good health.‹/p›

‹p›There are many kinds of kimchi, cabbage kimchi, radish kimchi,

cucumber kimchi, but cabbage kimchi is the most famous and served

in restaurants as a side dish breakfast, lunch, dinner and midnight

snack.‹/p›

114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-150-2048.jpg)

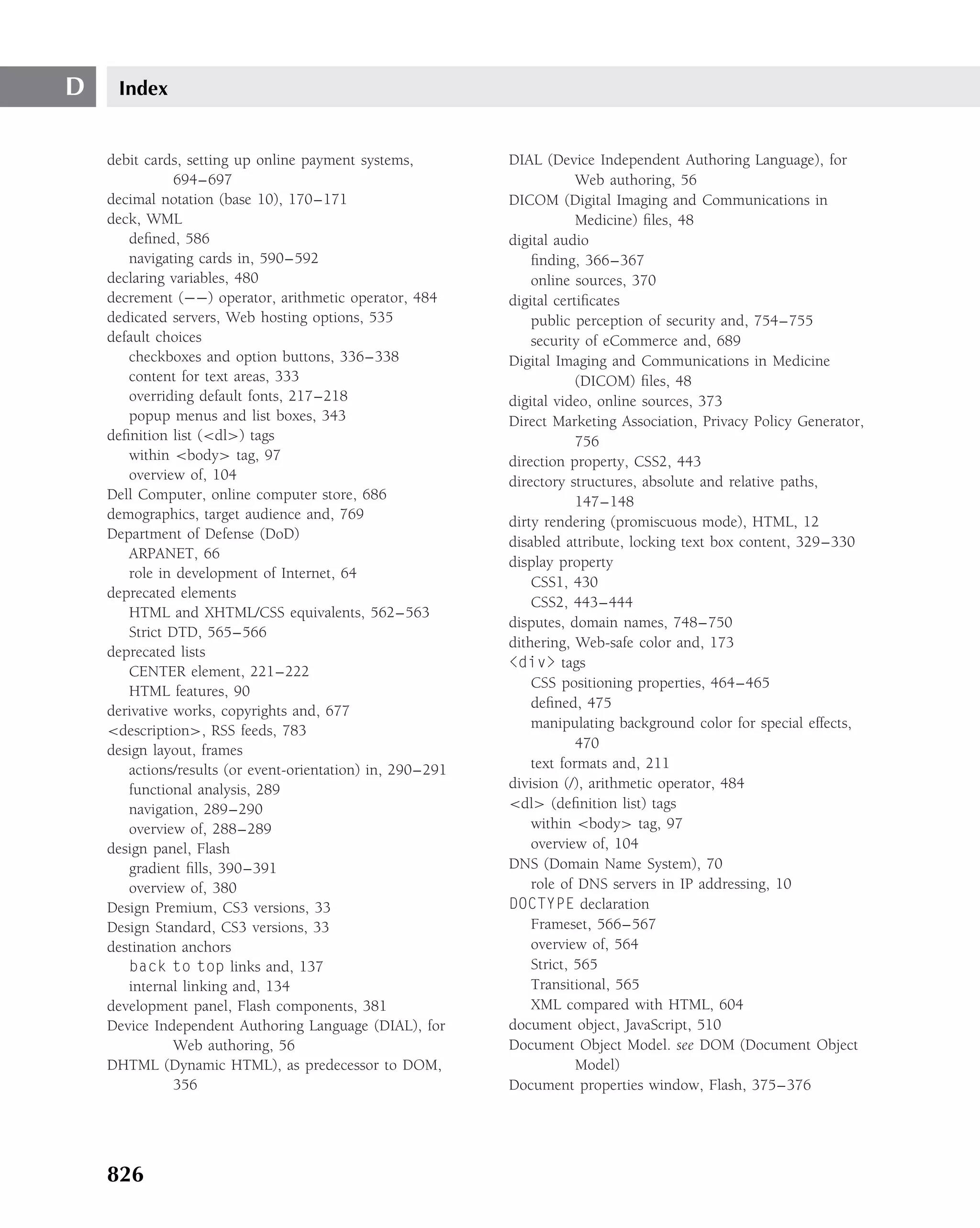

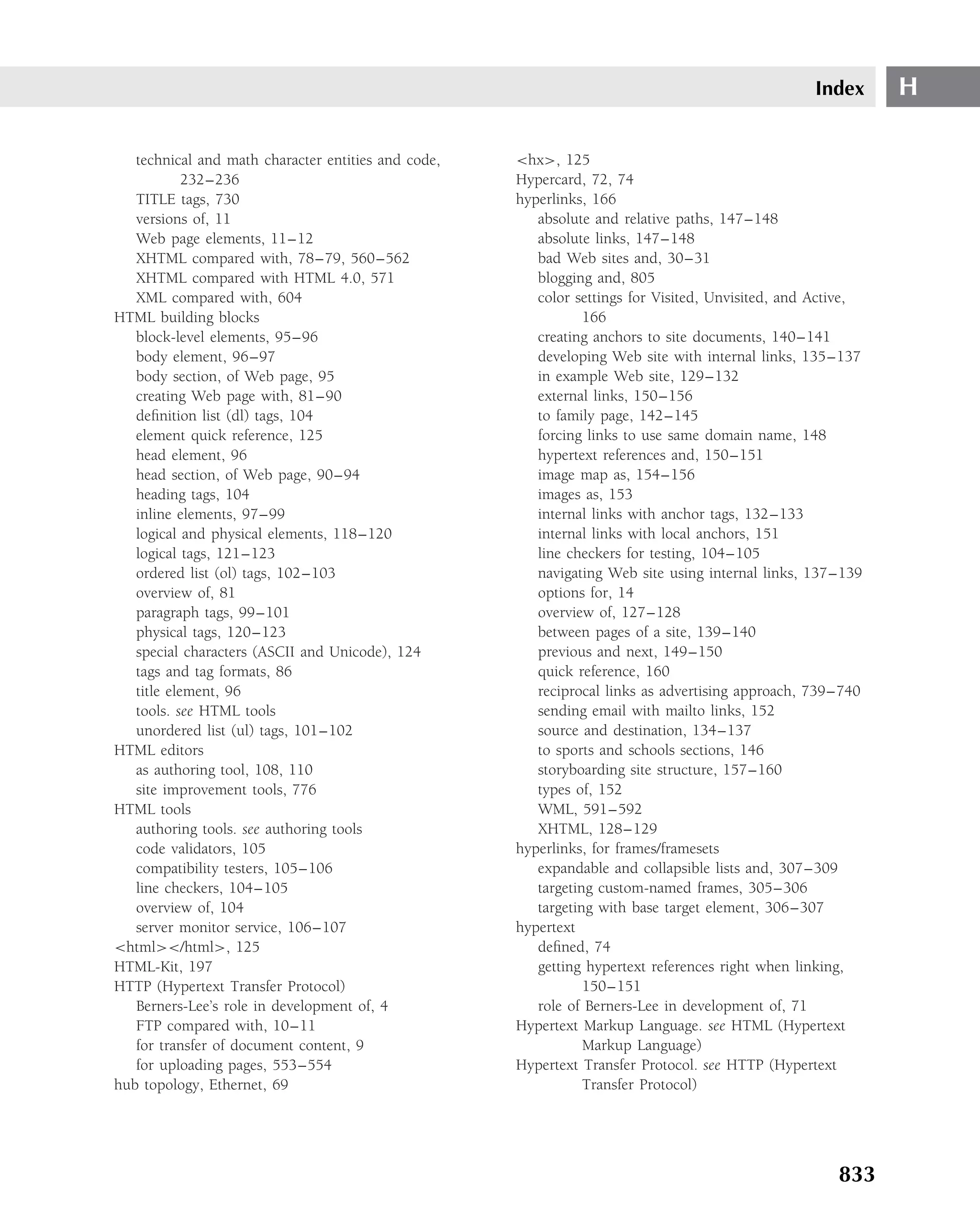

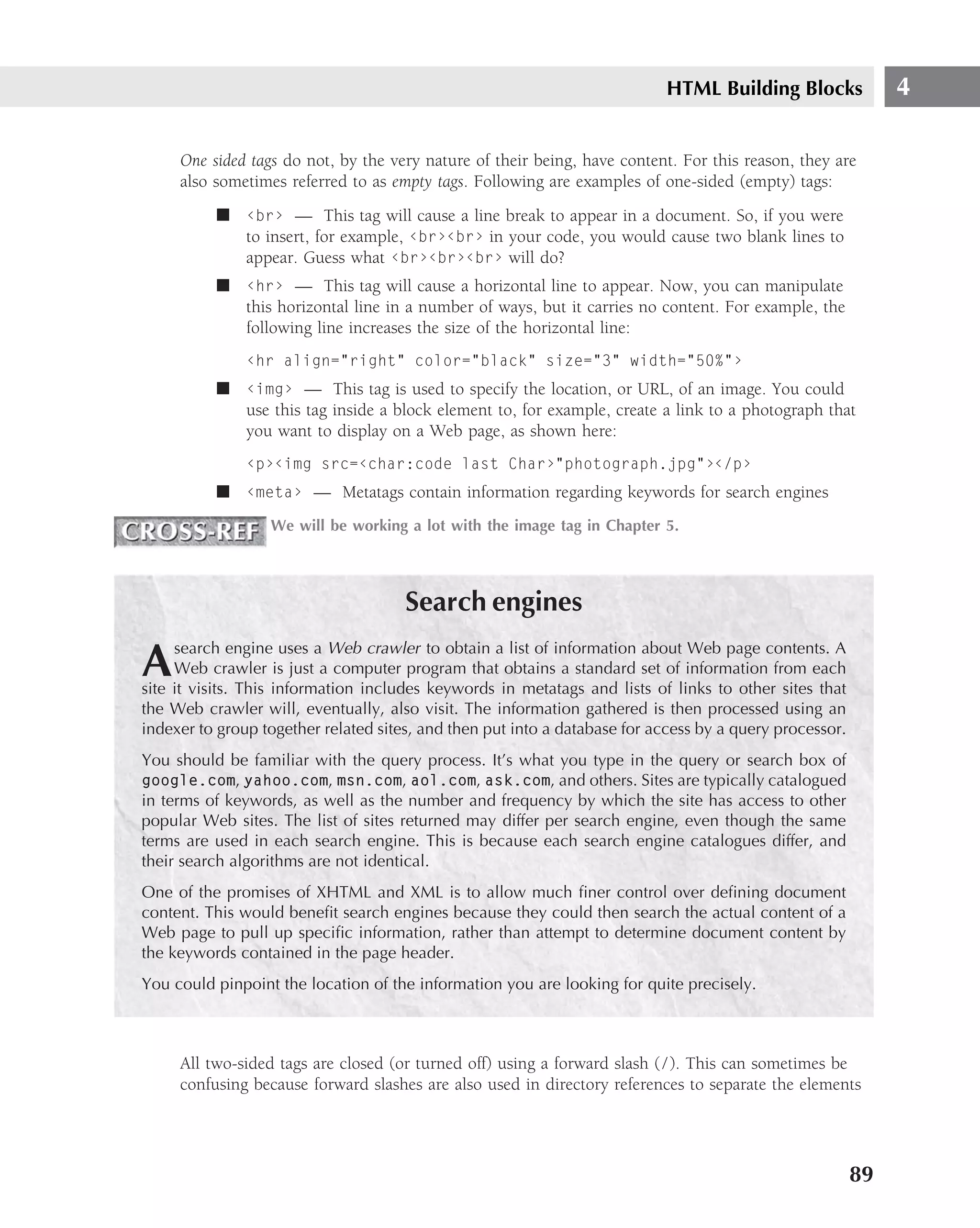

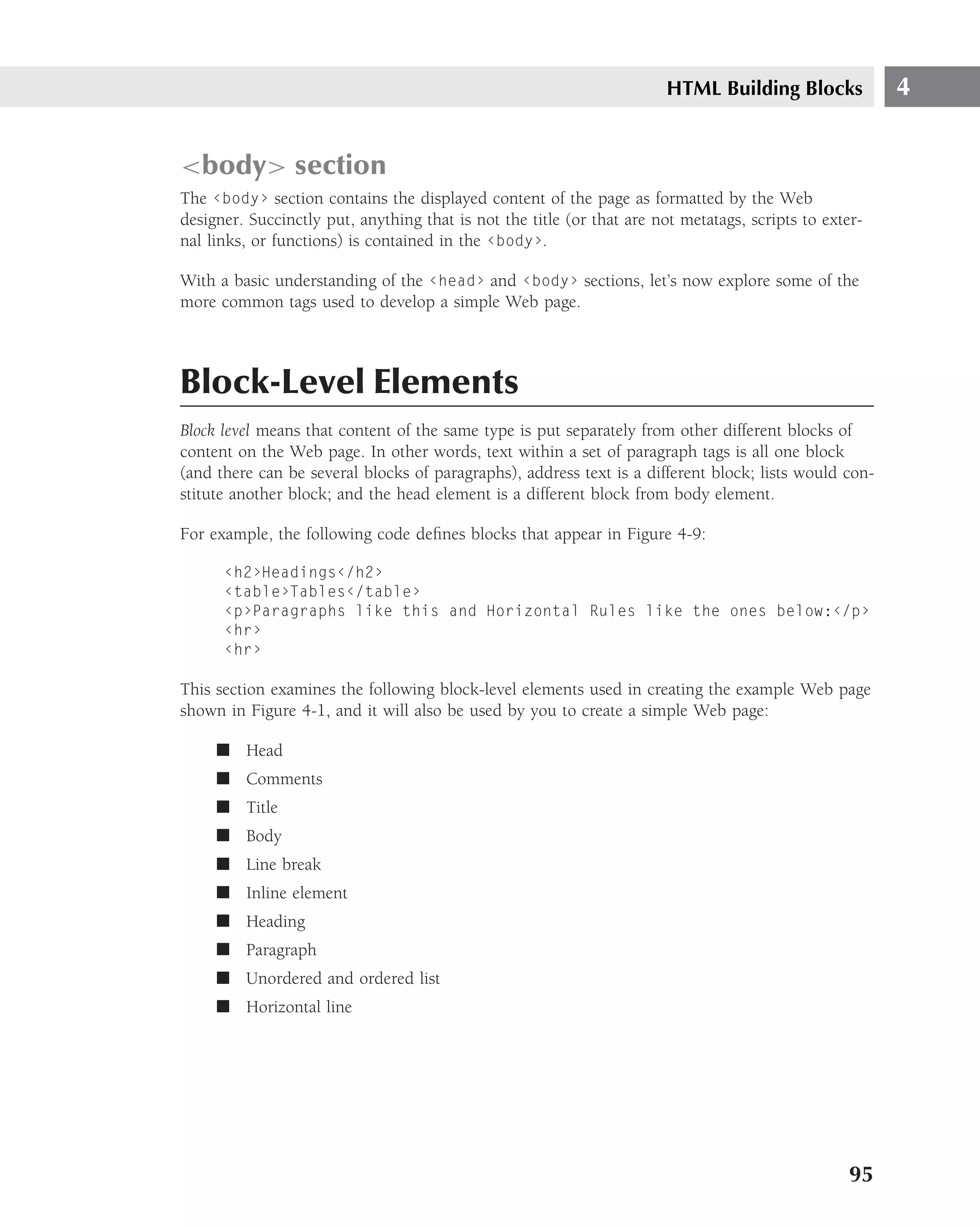

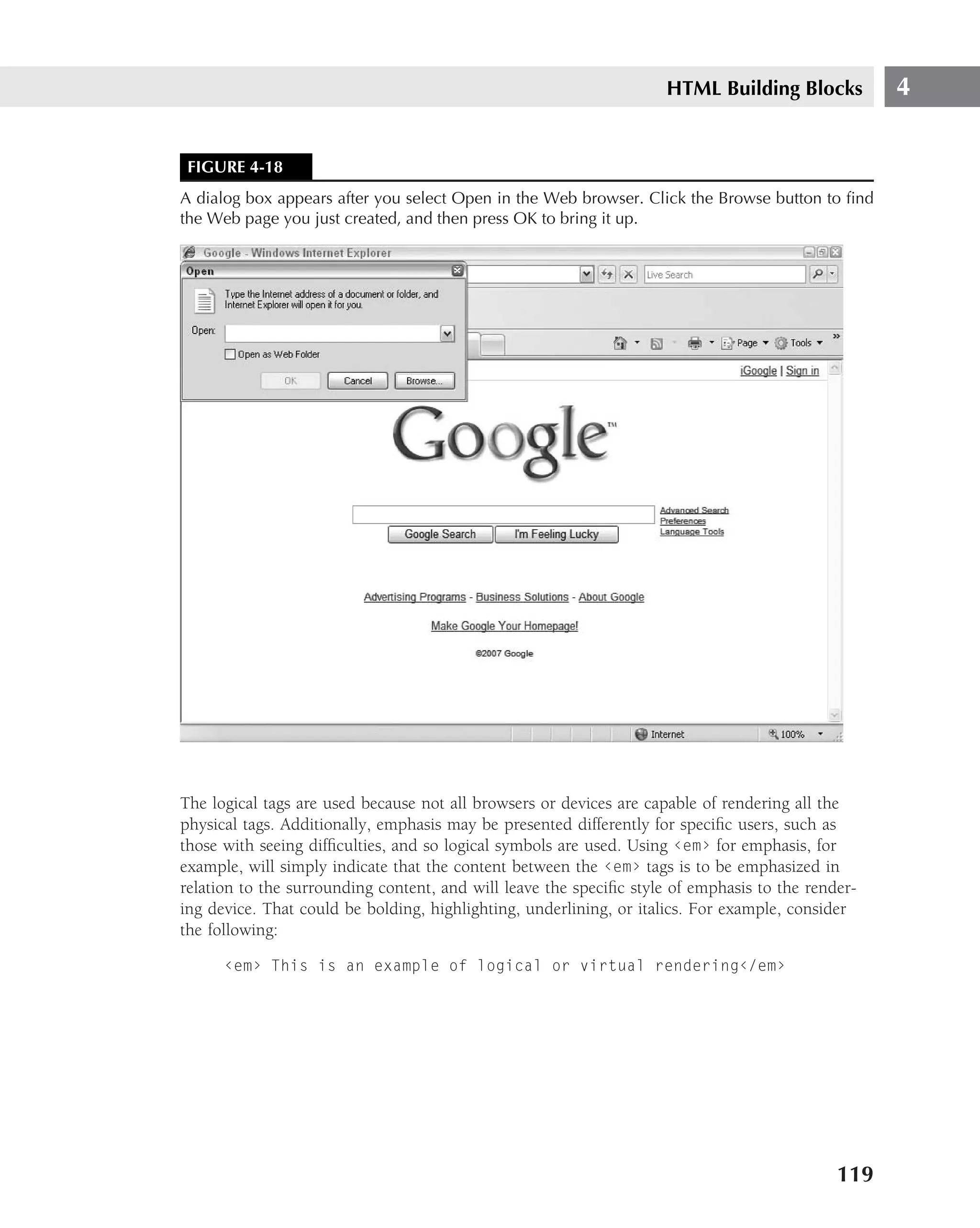

![HTML Building Blocks 4

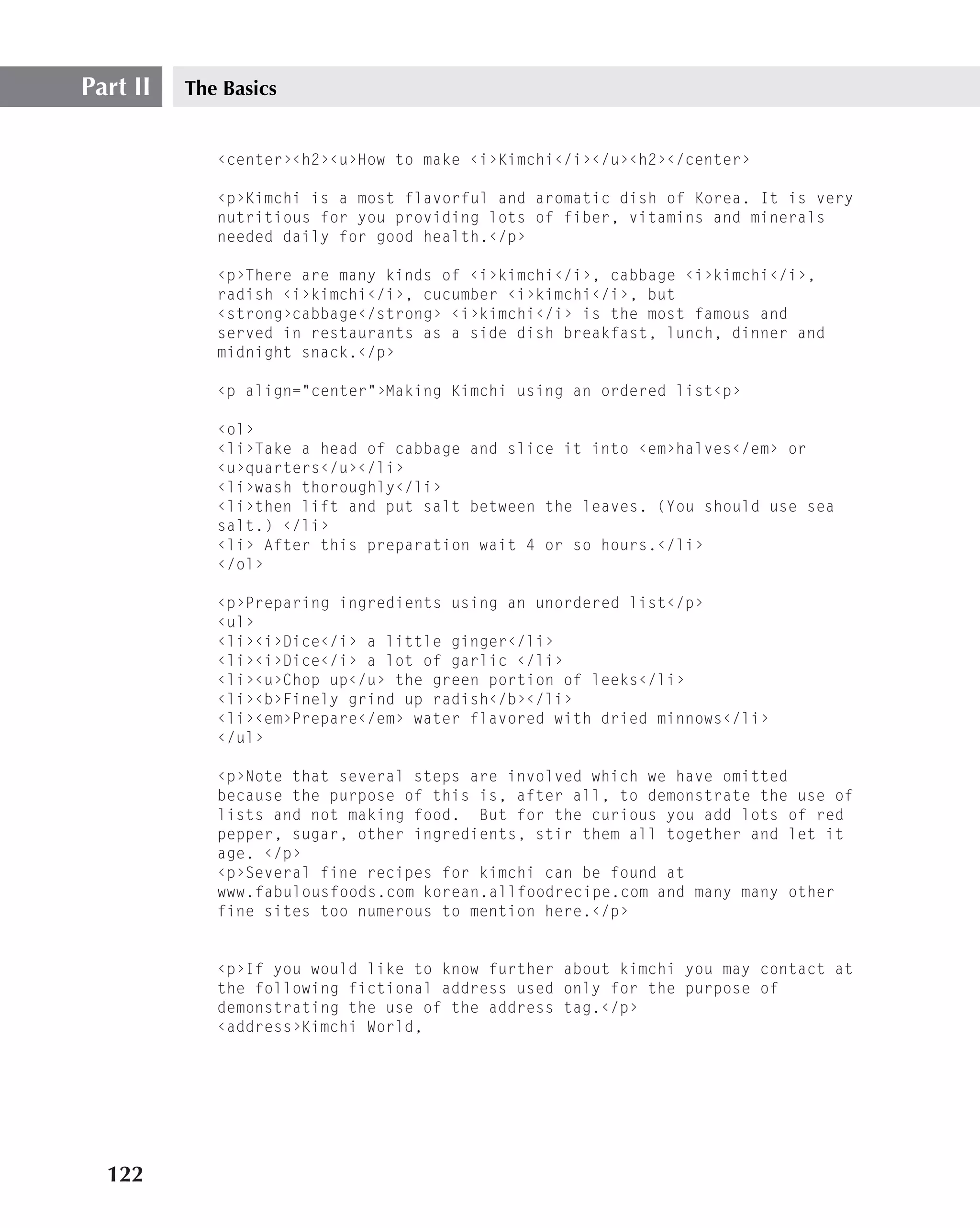

Logical tags

Here are some common logical tags:

‹abbr›TCP/IP‹/abbr›

‹acronym›SONET‹/acronym›

‹cite›Don’t quote me on this, but... ‹/cite›

‹code›if (form.query.value=="") {

alert(’Please make an entry in the product search

field.’);

return false;

} else {

return true;

} ‹/code›

‹dfn›terms and definitions‹/dfn›

‹em›italic can be emphasis‹/em›

‹strong›Strong and Bold‹/strong›

Logical tags do not include any final rendering guidelines. They describe instead how the con-

tent is to be represented in the context of the document. The benefit of logical tags is that the

intent of the programmer can still be carried out.

Practice with tags of both styles and you will develop a subset of tags that fit your preferences as

a developer to meet your programming needs.

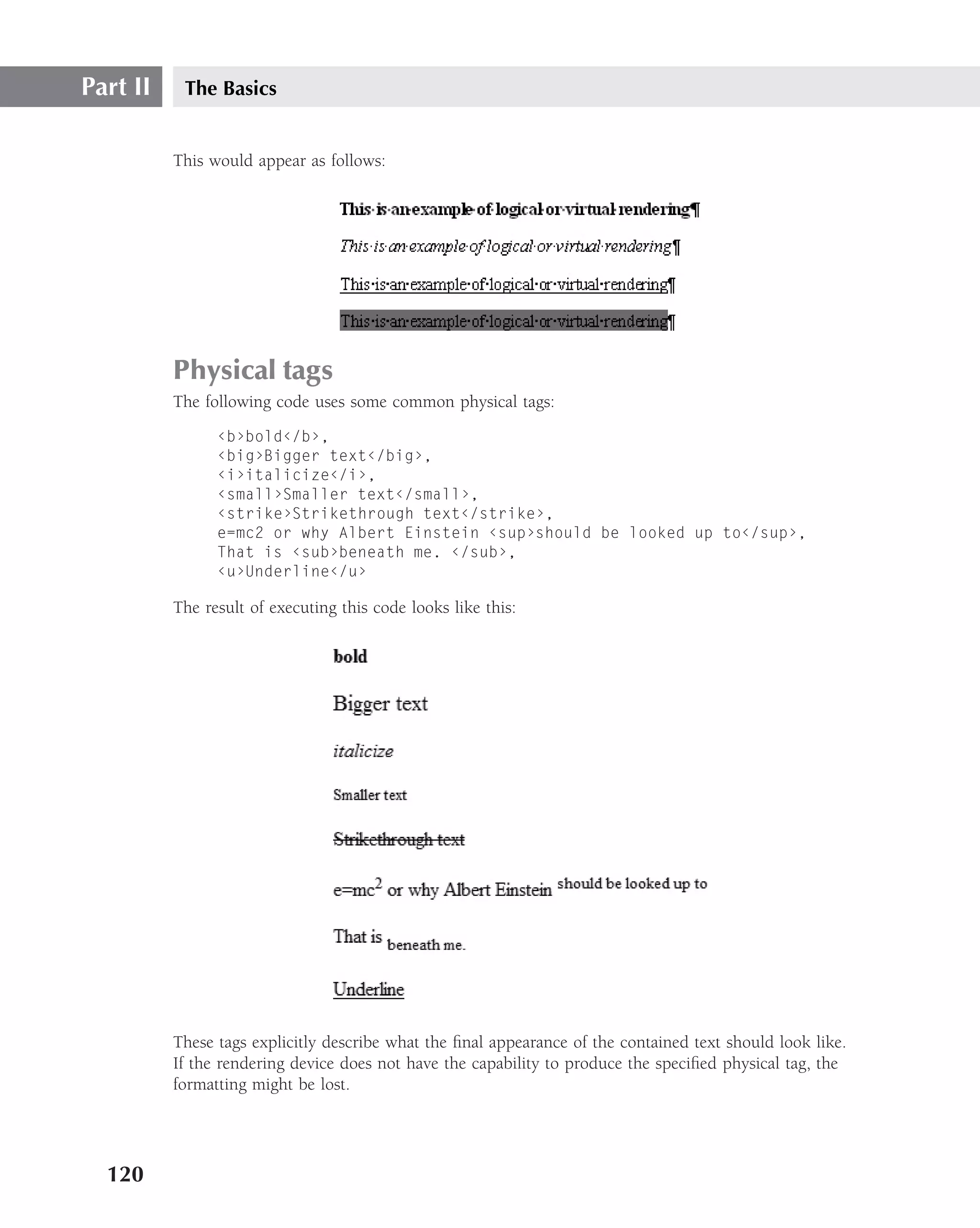

Incorporating logical and physical tags

Now, let’s work with some of those elements just described for your Web page. Let’s use the fol-

lowing tags: ‹b›, ‹i›, ‹u›, ‹center›, ‹hx› (where x represents any number between 1 and

6), ‹em›, and ‹strong›. Enter the following code:

‹html›

‹head›

‹title› A first demonstration of tags‹/title›

‹!--This web page was constructed by [your name] on [insert date].

Its purpose is to demonstrate the use of the following tags: ‹b›,

‹i›, ‹u›, ‹center›, ‹hx› (where x represents any number between 1 and 6),

and ‹em›, ‹strong› --›

‹/head›

‹body›

121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-157-2048.jpg)

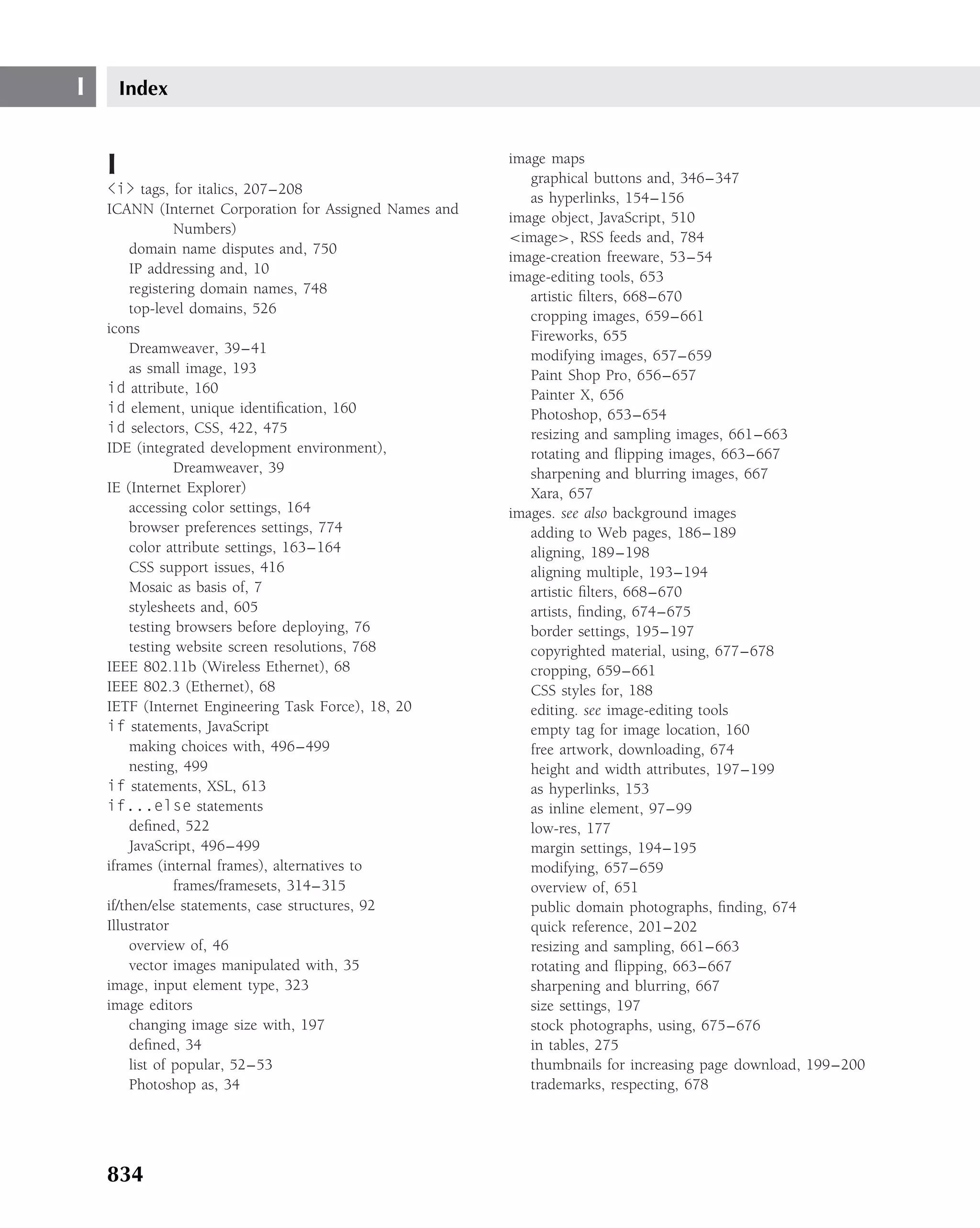

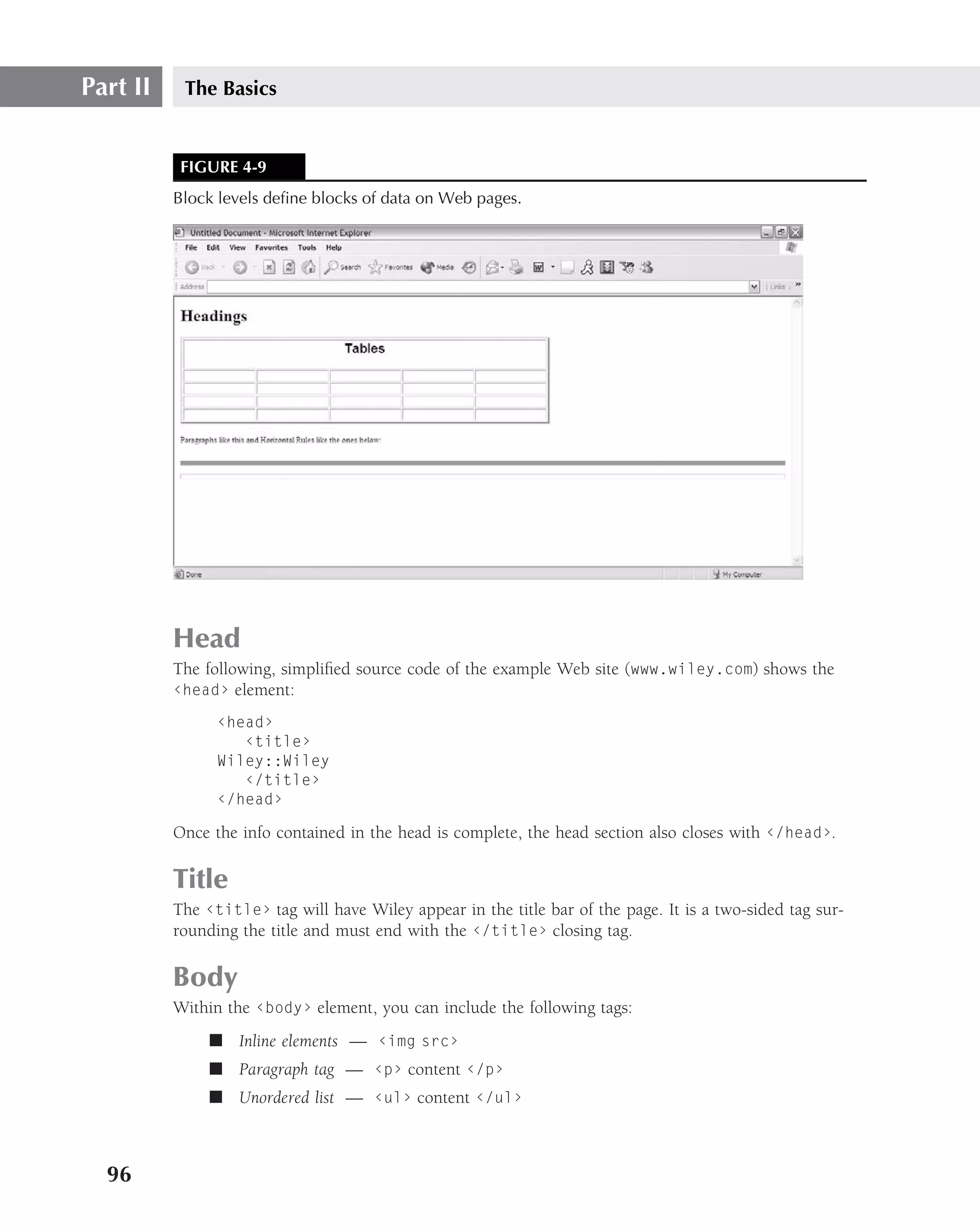

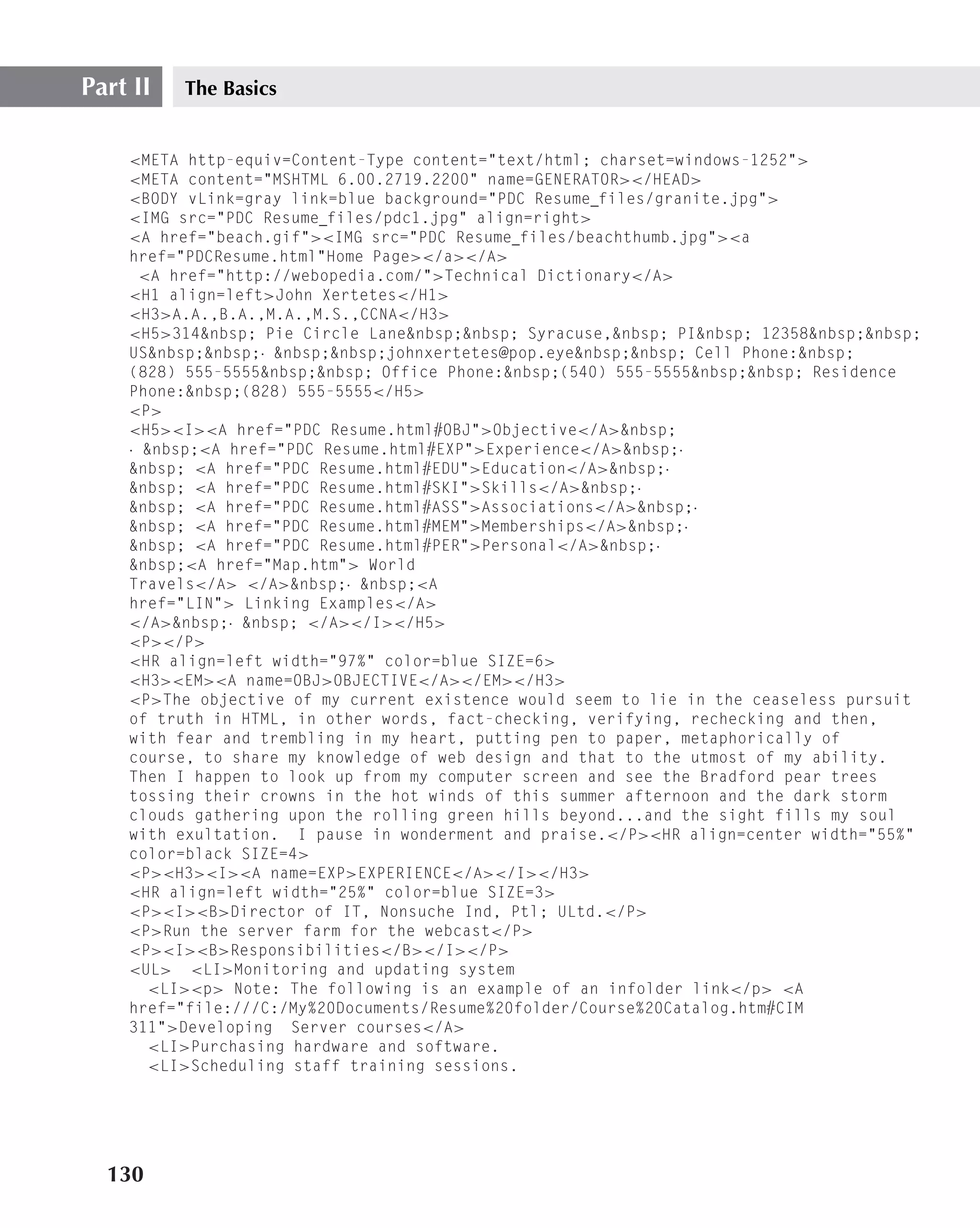

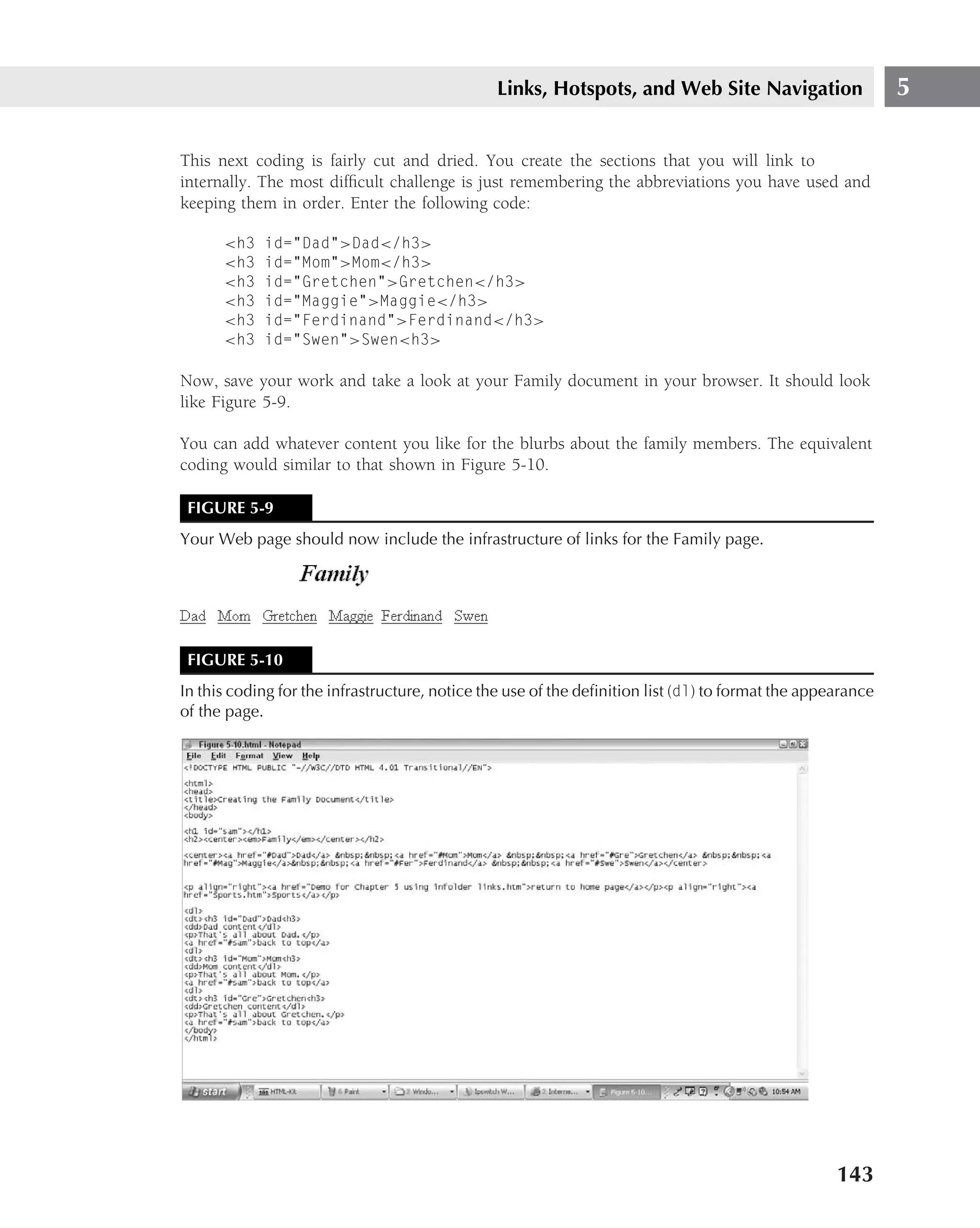

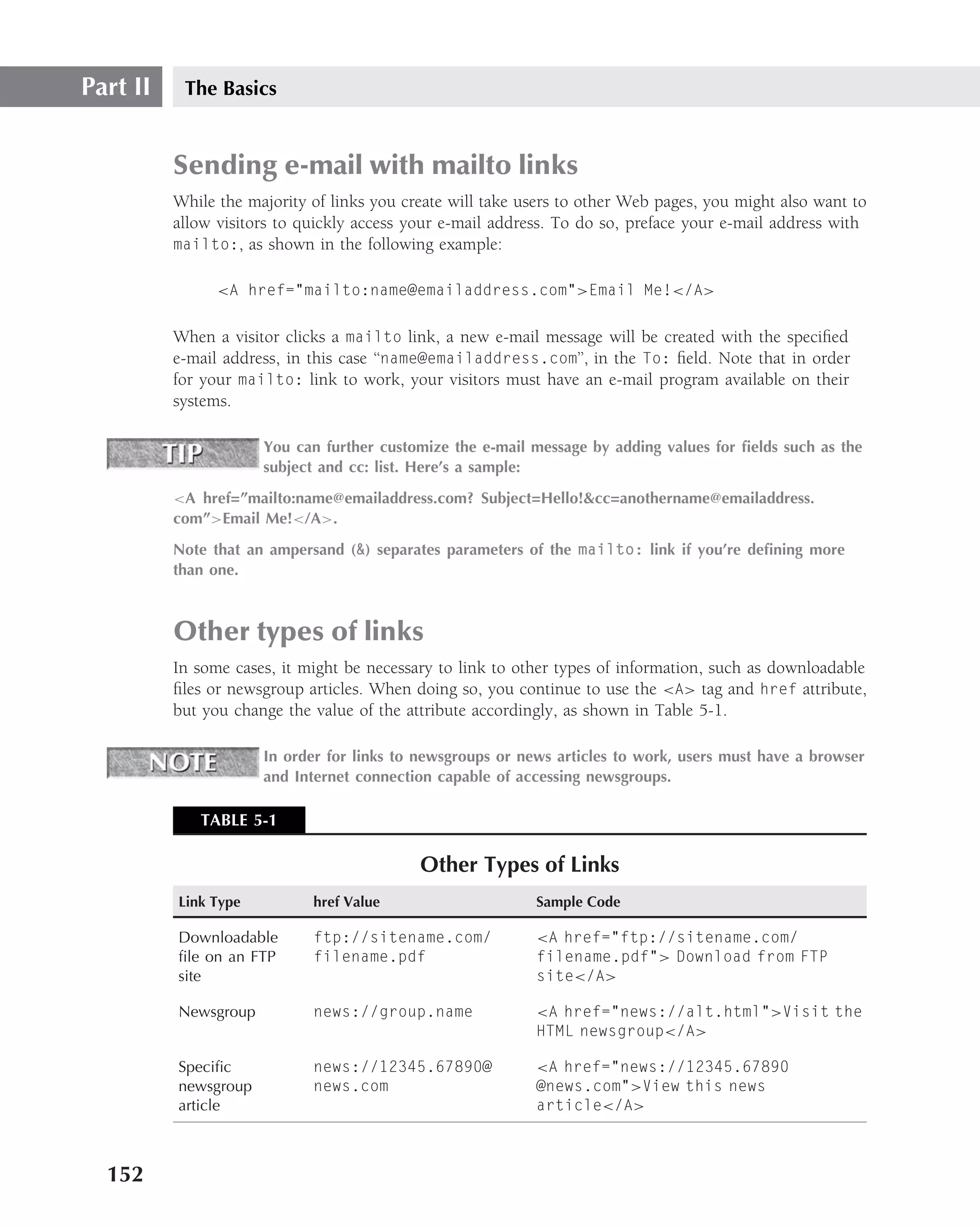

![Links, Hotspots, and Web Site Navigation 5

continued

<link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style.css" type="text/css"

rel="stylesheet">

<title>

Wiley::Wiley

</title>

<script language="javascript" src="/WileyCDA/site/shared/form validation.js"

type="text/javascript">

</script>

<!--[if lt IE 7]>

<link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style-ie.css" rel="stylesheet"

type="text/css">

<!--[endif]-->

</head>

The tag, as currently implemented, appears only in the <head> section of the document.

As you can see in the line <link href="/WileyCDA/site/wiley2/include/style.css"

type="text/css" rel="stylesheet">, the link refers to a stylesheet, style.css, located on

the WileyCDA site. The second link refers to another stylesheet, style-ie.css, in the same

location as the first link tag.

If you were to look at more link tags in the source code of this site, you would see that they all

appear in the <head> section, and they all refer to stylesheets. What you may reasonably infer

from this is that the link tag has limited applicability at present. The link tag may eventually have

broader application, but it is presently mostly used only in the <head> section of a document to

link to stylesheets.

And, as you now know, any element in the <head> does not appear in a Web browser’s content

pane.

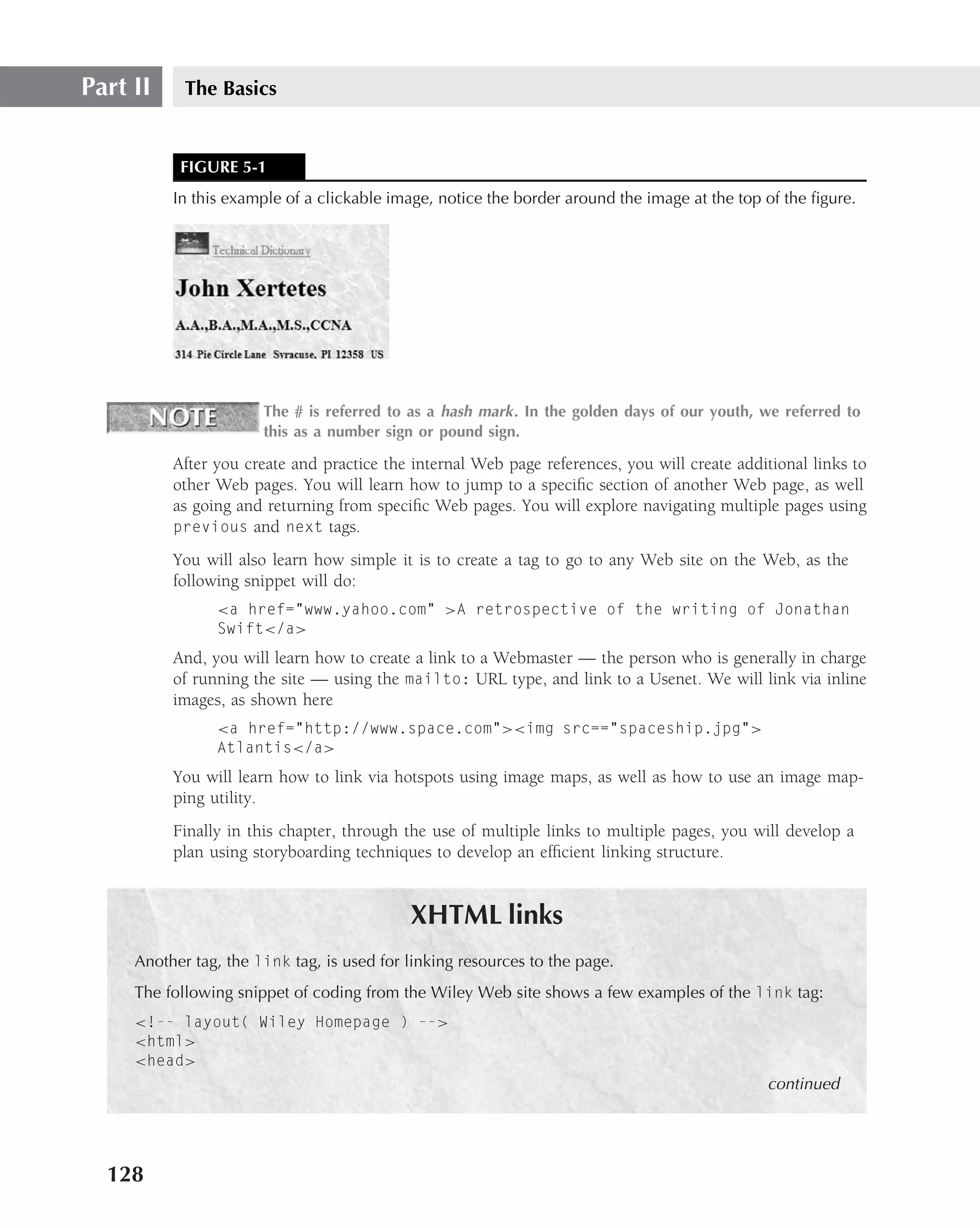

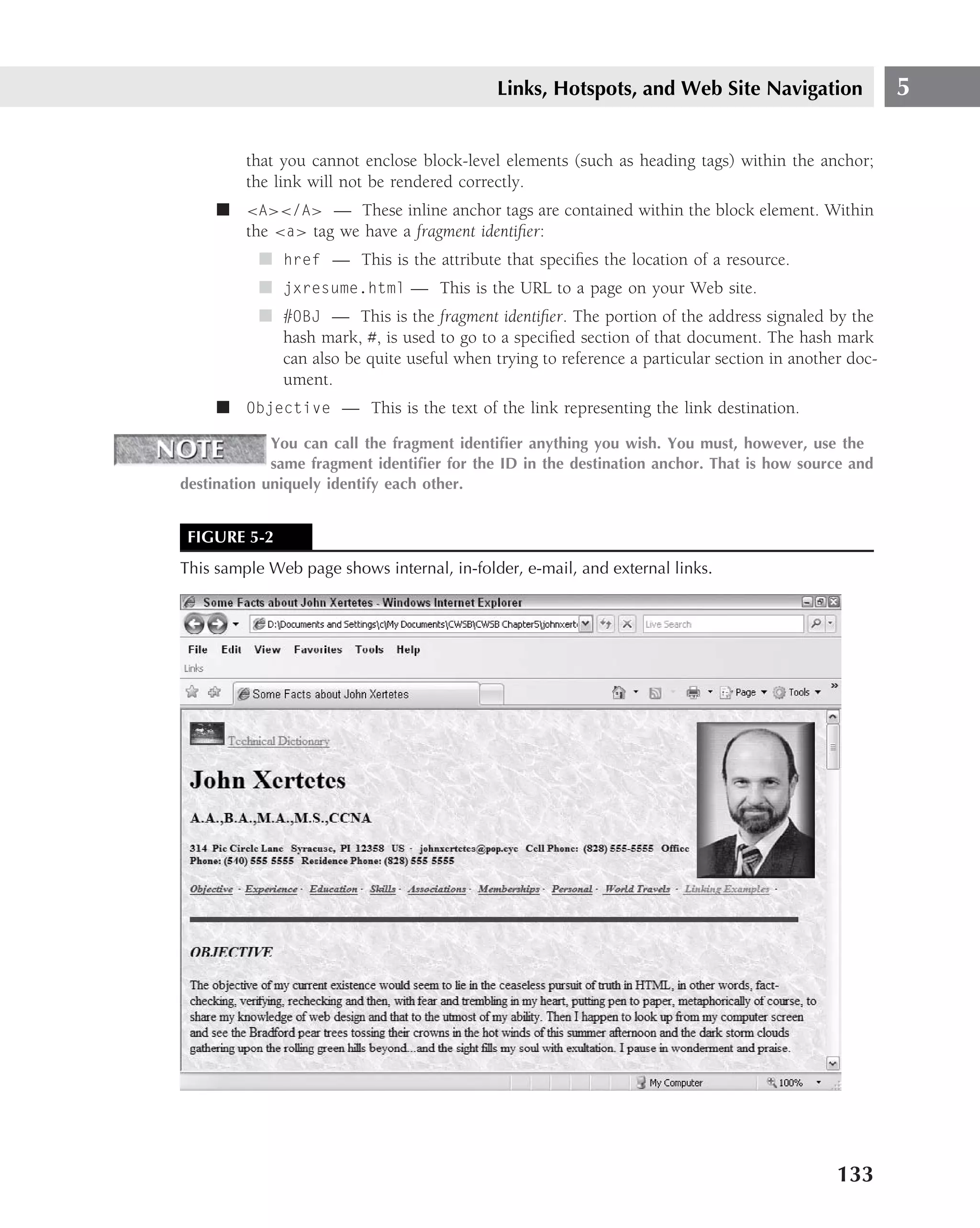

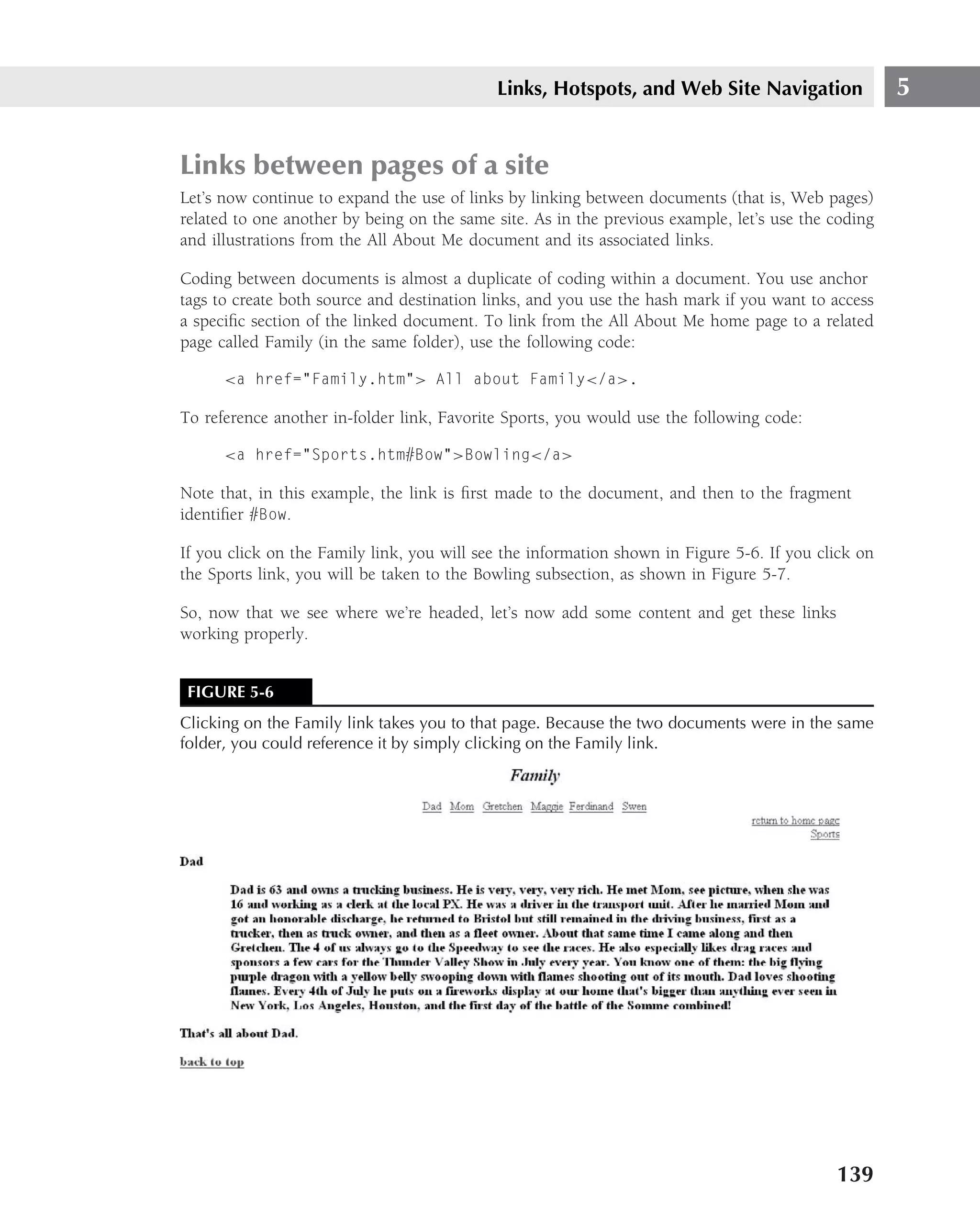

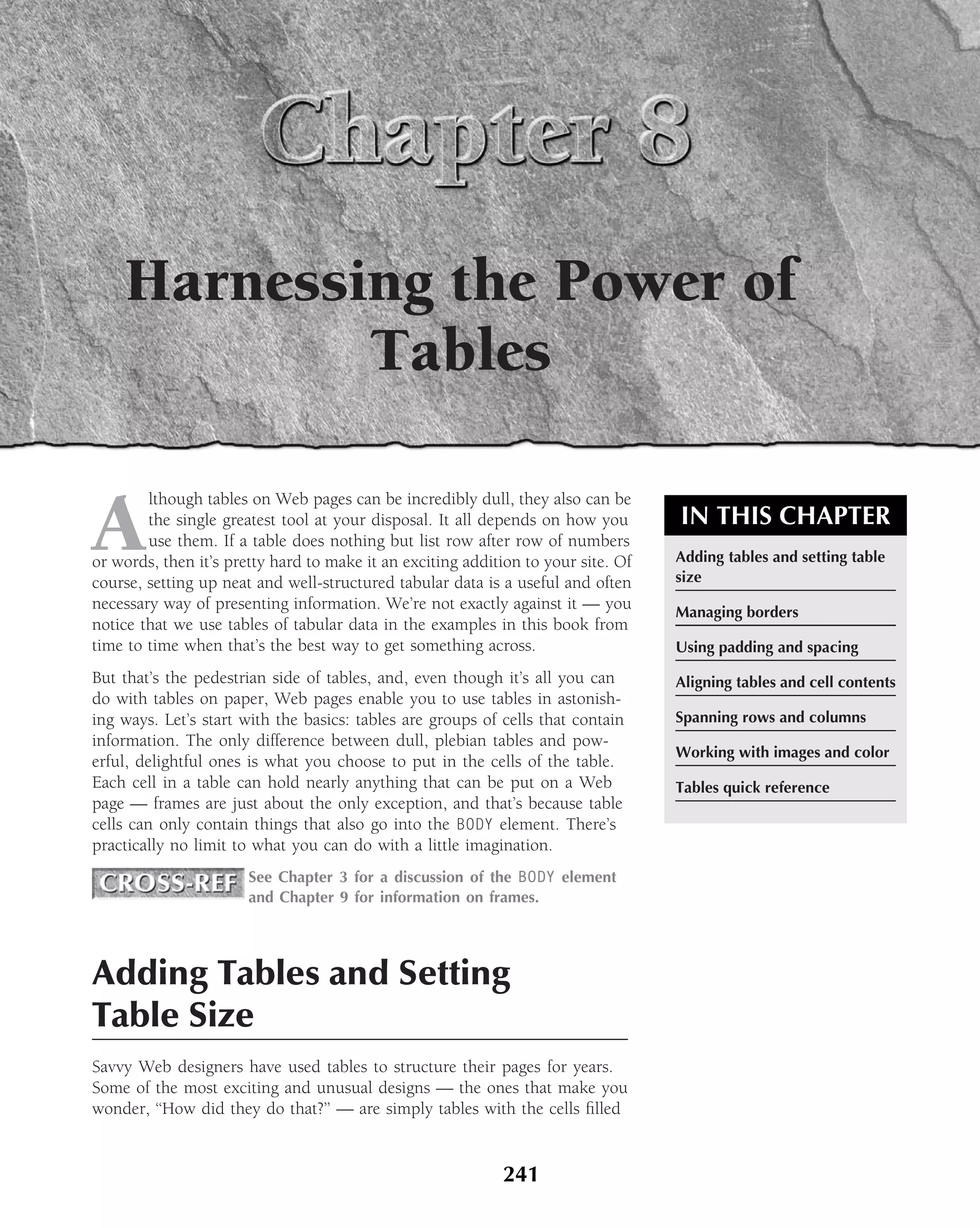

Example Web Site

Listing 5-1 shows the source code of a site used in some of the examples for this chapter. The

purpose of the source code shown here is to introduce the reader to several additional features

of a Web page with links to other sites. This site incorporates links (internally and externally),

images, and image maps. Each of the new features will be explained in context of the page, and

then further illustrated in separate sections of the chapter.

LISTING 5-1

Example Source Code

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN">

<HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Some Facts about John Xertetes</TITLE>

129](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-165-2048.jpg)

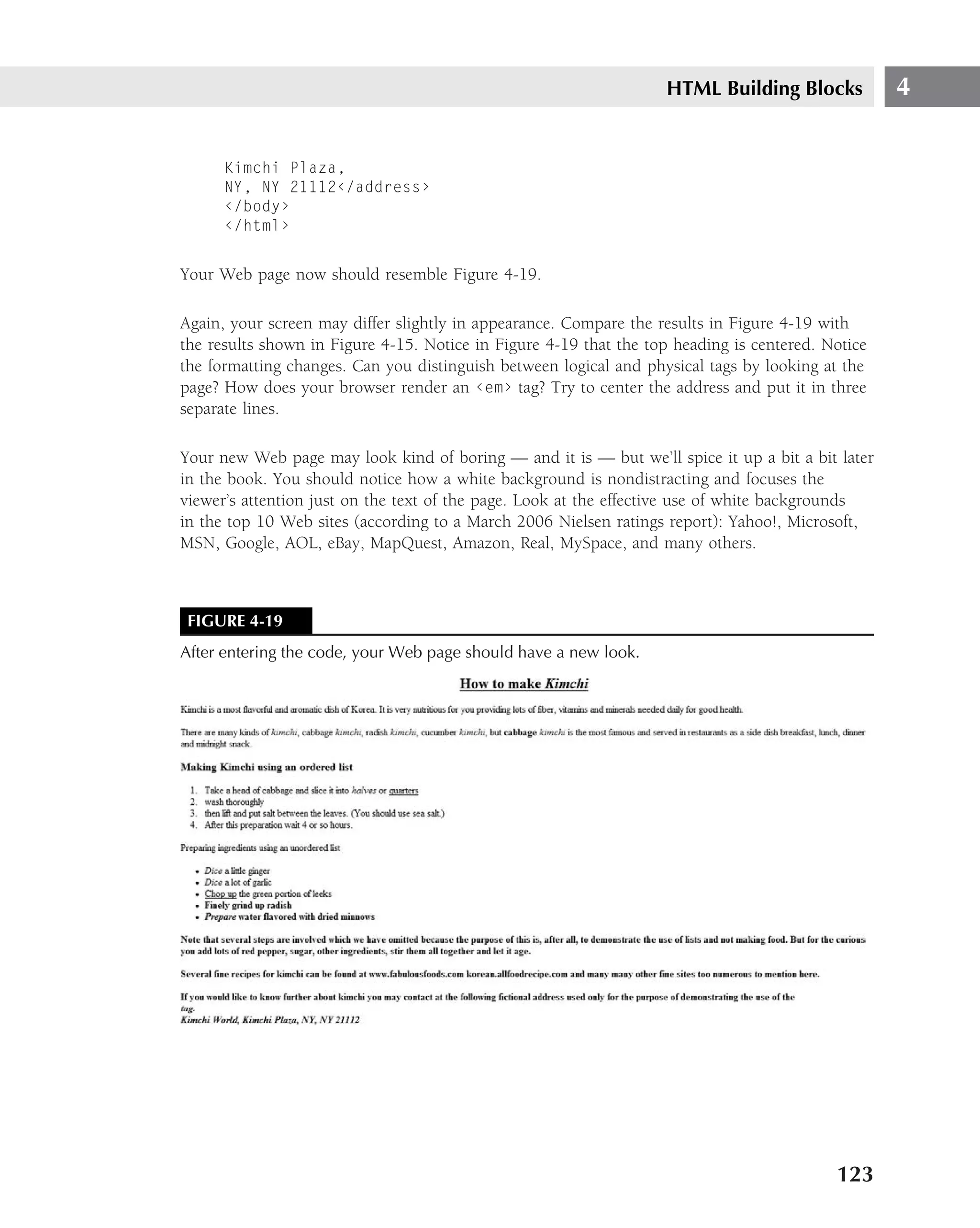

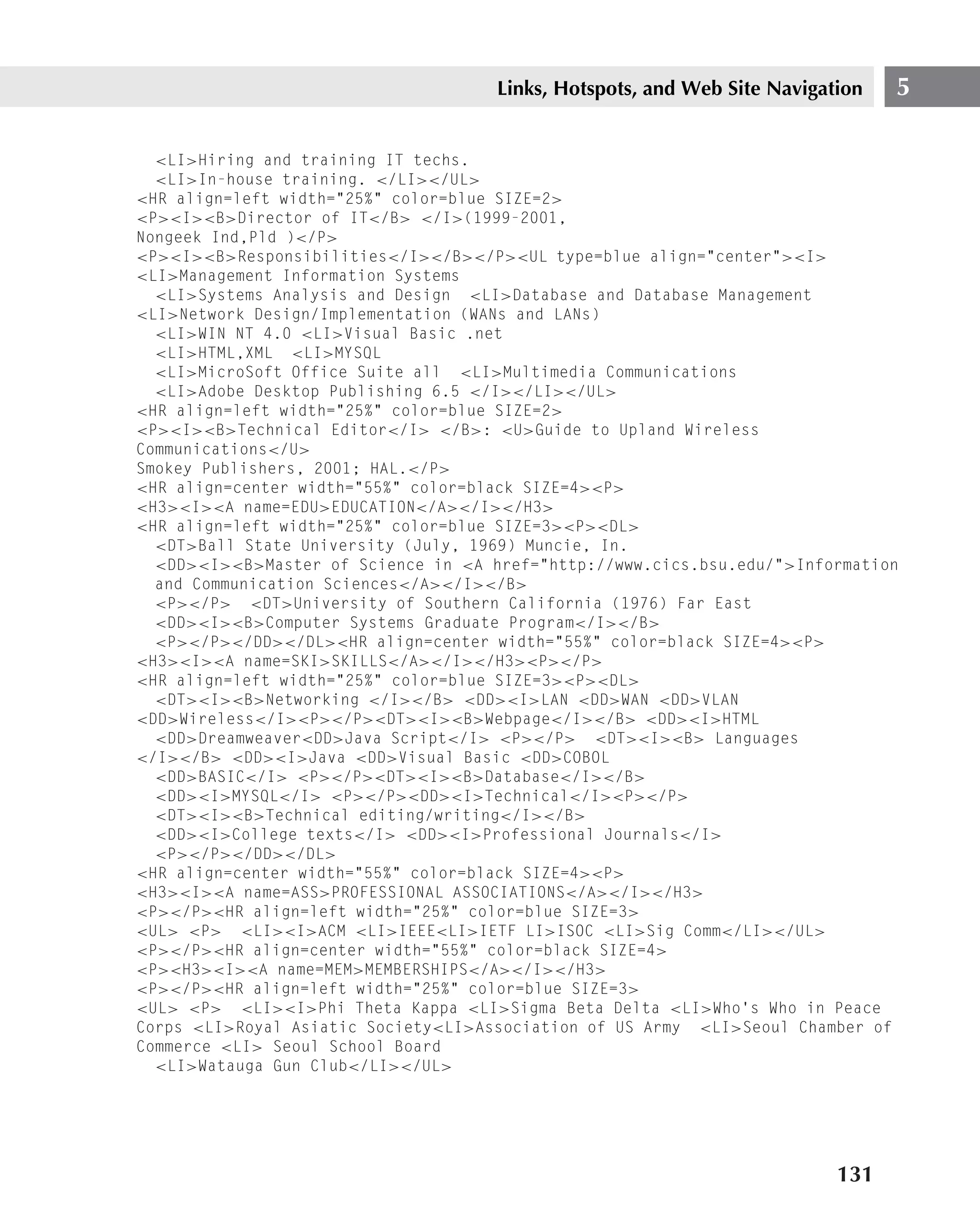

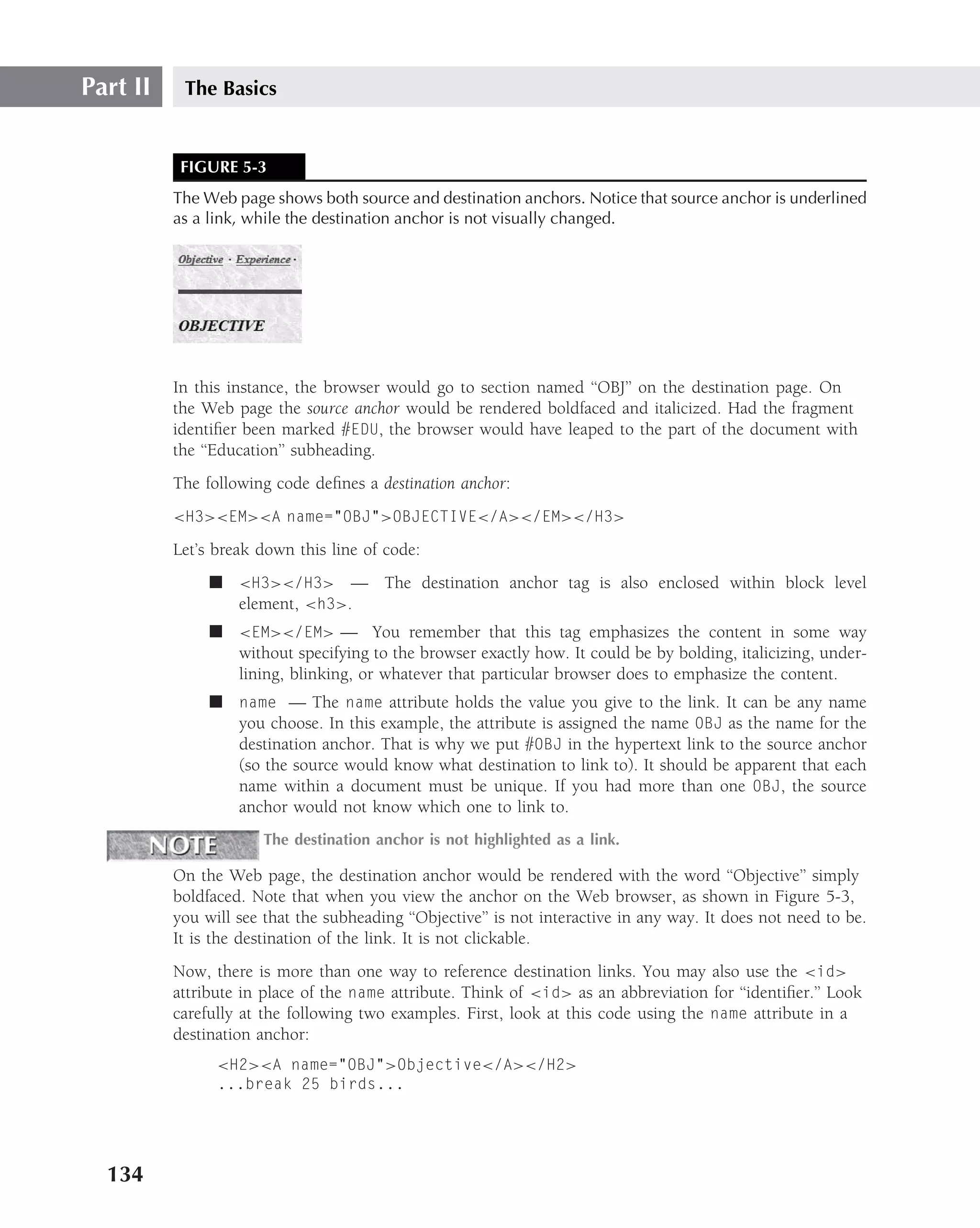

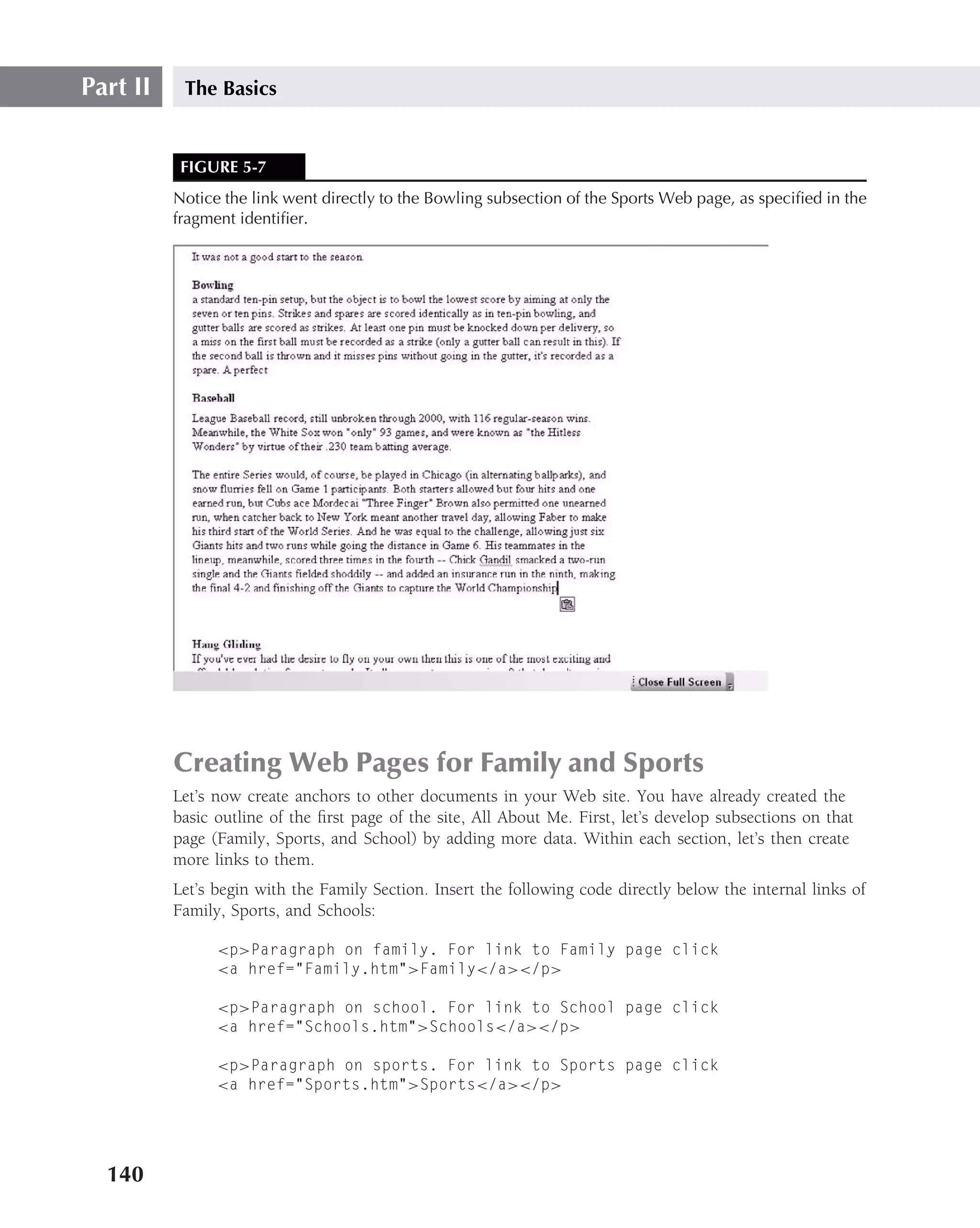

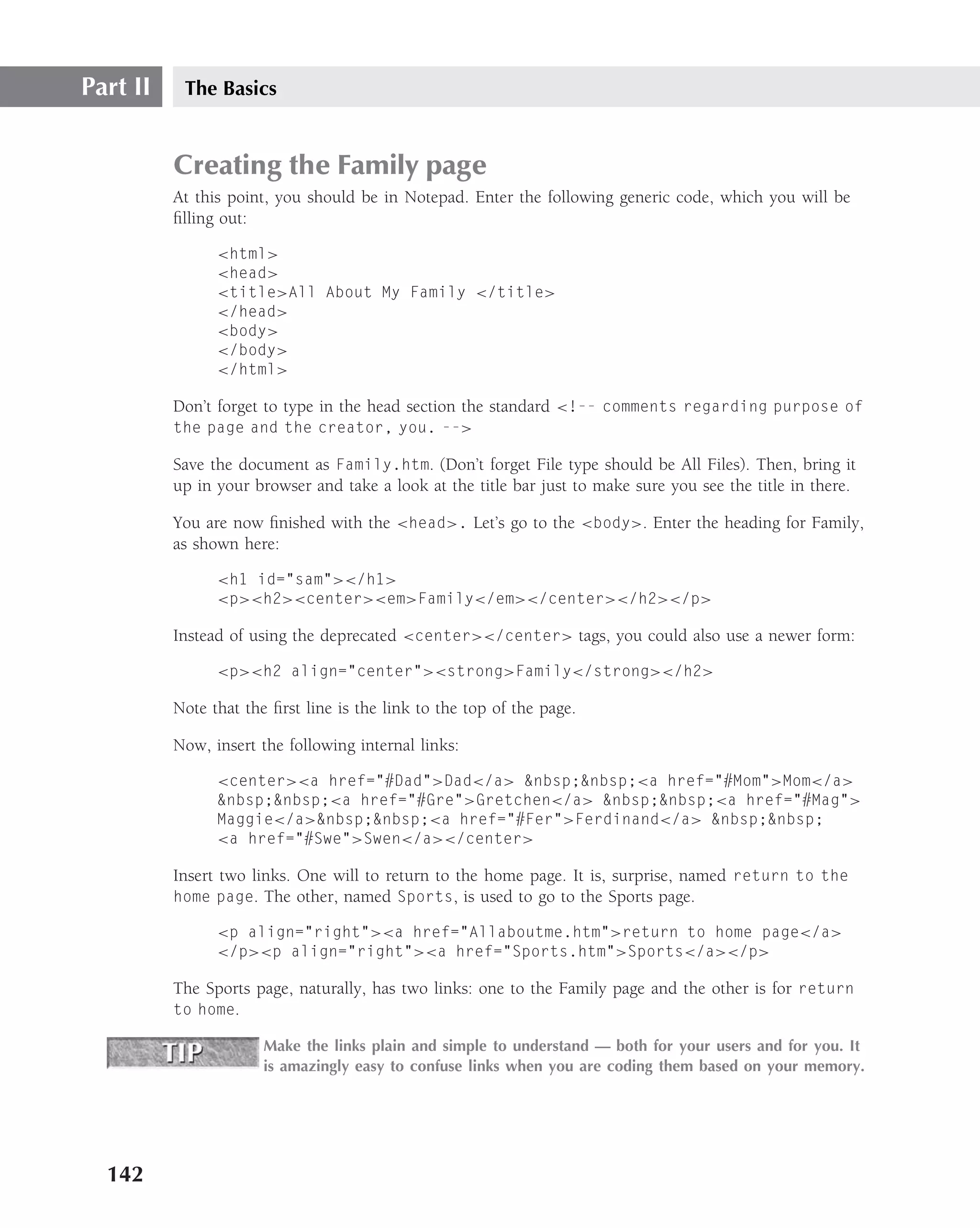

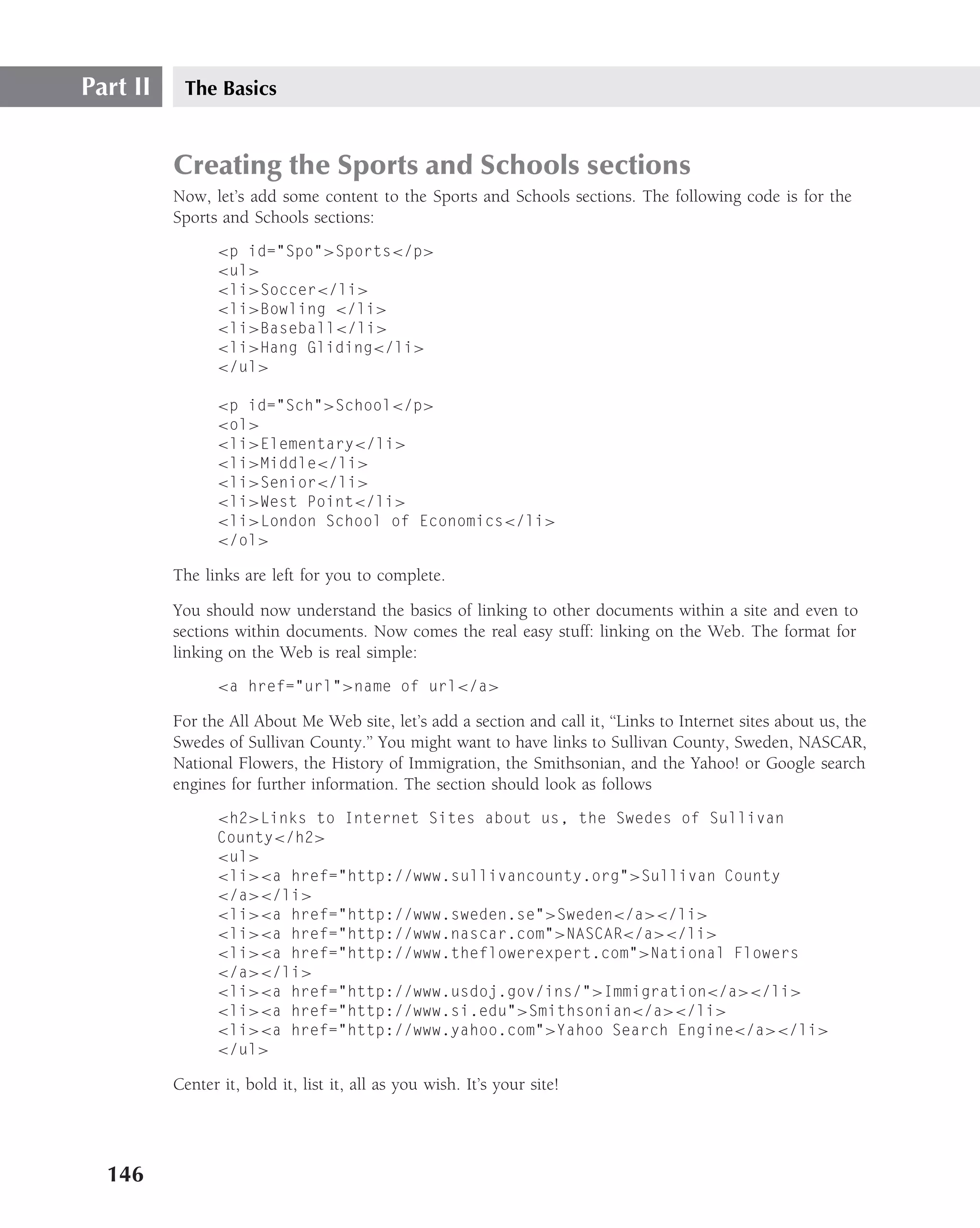

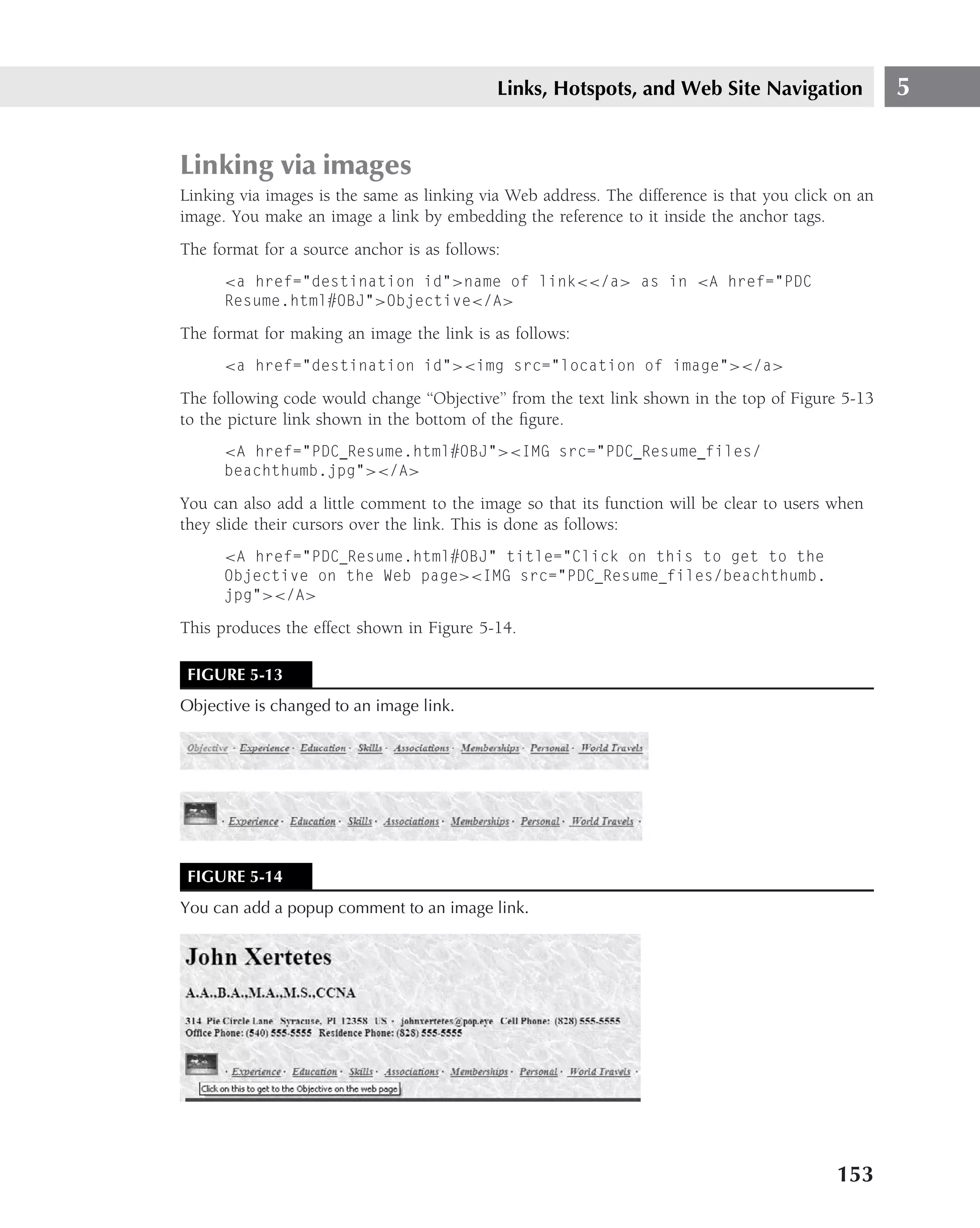

![Part II The Basics

2. Now, go to the File menu and select Save As. Save the file with the name AllAboutMe.

htm (do not forget the htm extension!). Ensure that the File Type is All Files. Save this

file in a folder called Chapter 5, for example, and save it either in your My Doucuments

folder or on your Desktop so that it’ll be easy to find.

Remember to save this file, and the other files you will be creating, in the same folder

3. Next, go to your Web browser, and open the site using the Browse button on the dialog

box.

4. Verify that the title bar shows ‘‘All About Me’’ in the title. There should be nothing on

the screen, of course. You haven’t input any content in the body, yet.

5. Close the page and open Notepad again, and add the following comments in the

<head> section.

<!-- This web page was constructed by [your name] on [insert

date]. Its purpose is to demonstrate the use of source and

destination anchors using, hash mark, and both id and Name

attributes. These will be demonstrated by the development of an

autobiographical web Page -->

6. Within the <body> section, center an h2 size of heading that will appear at the top of

your Web page. Emphasize it in some way.

7. Now, make three links three lines below the heading. Enter the following code exactly:

<p><center><a href="#Fam">Family</a>

<a href="#Spo">Sports</a> <a

href="#Sch">Schools</a></center></p>

8. Go down a line. Put in a blue horizontal line all the way across the page. Go down two

lines using the <br> tag.

9. Enter the following code, exactly as shown:

<h2><a href Name=Fam>Family</a> </h2></p>

<p>Paragraph on family.</p>

<p id="Spo">Sports</p>

<p>Paragraph on sports</p>

<p id="Sch">School</p>

<p> Paragraph on school</p>

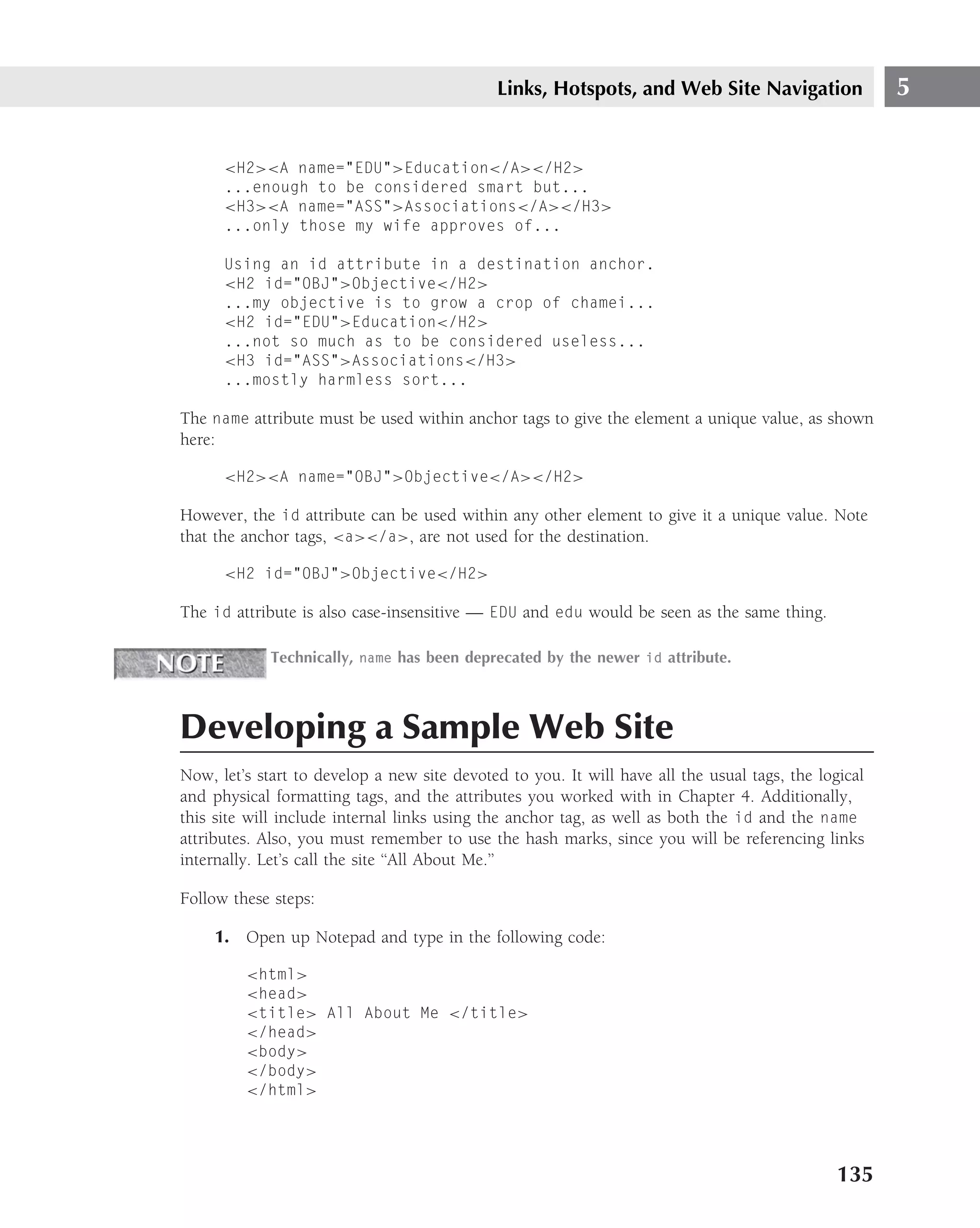

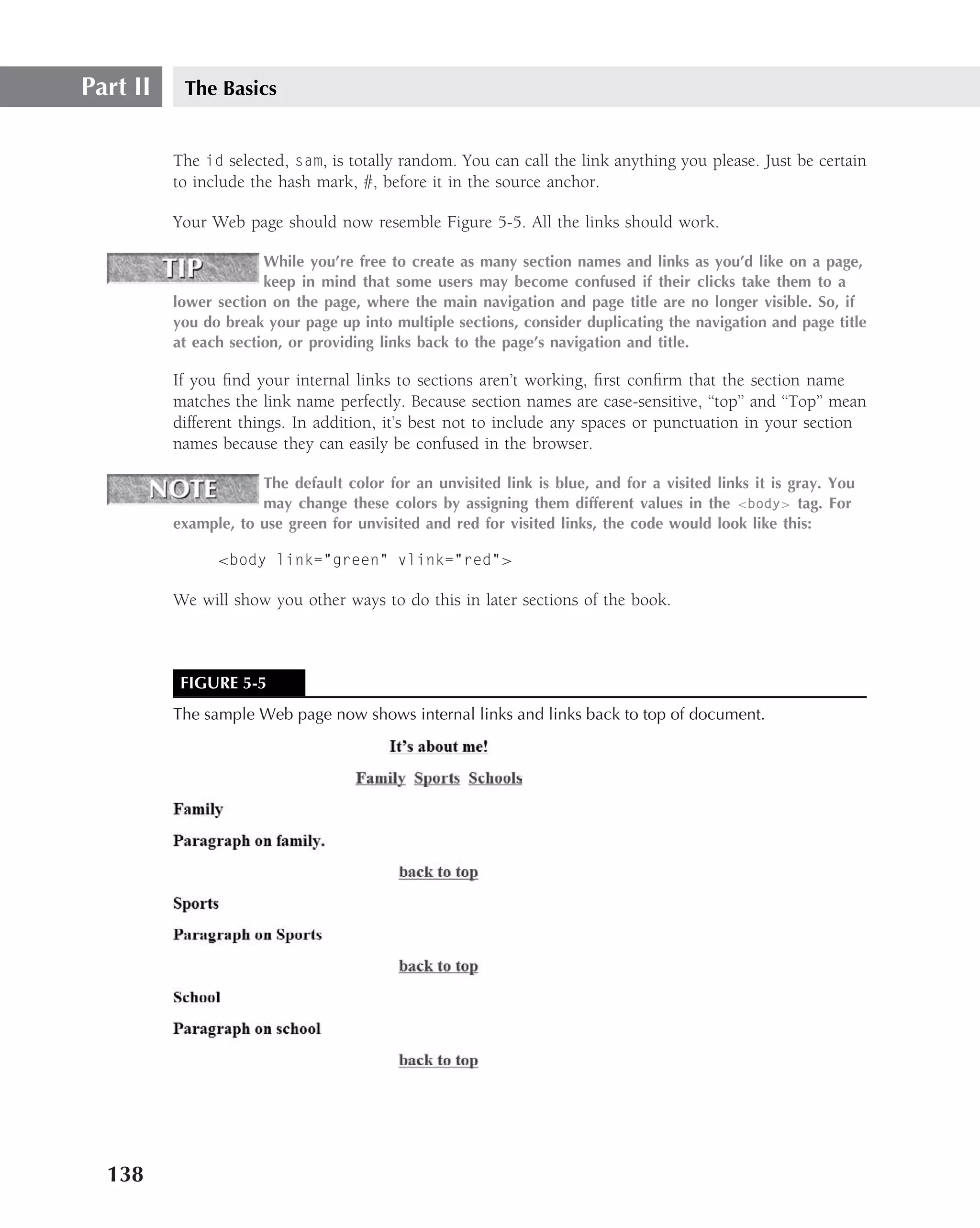

10. Save the file and bring it up in your browser. It should look something like Figure 5-4.

Test your links: They should work.

If your Web page doesn’t have working links, or if it looks substantially different from

Figure 5-4, go back and recheck your coding. You probably made an error in spelling or forgot

to close a tag. If you can’t find any errors, start over again.

136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-172-2048.jpg)

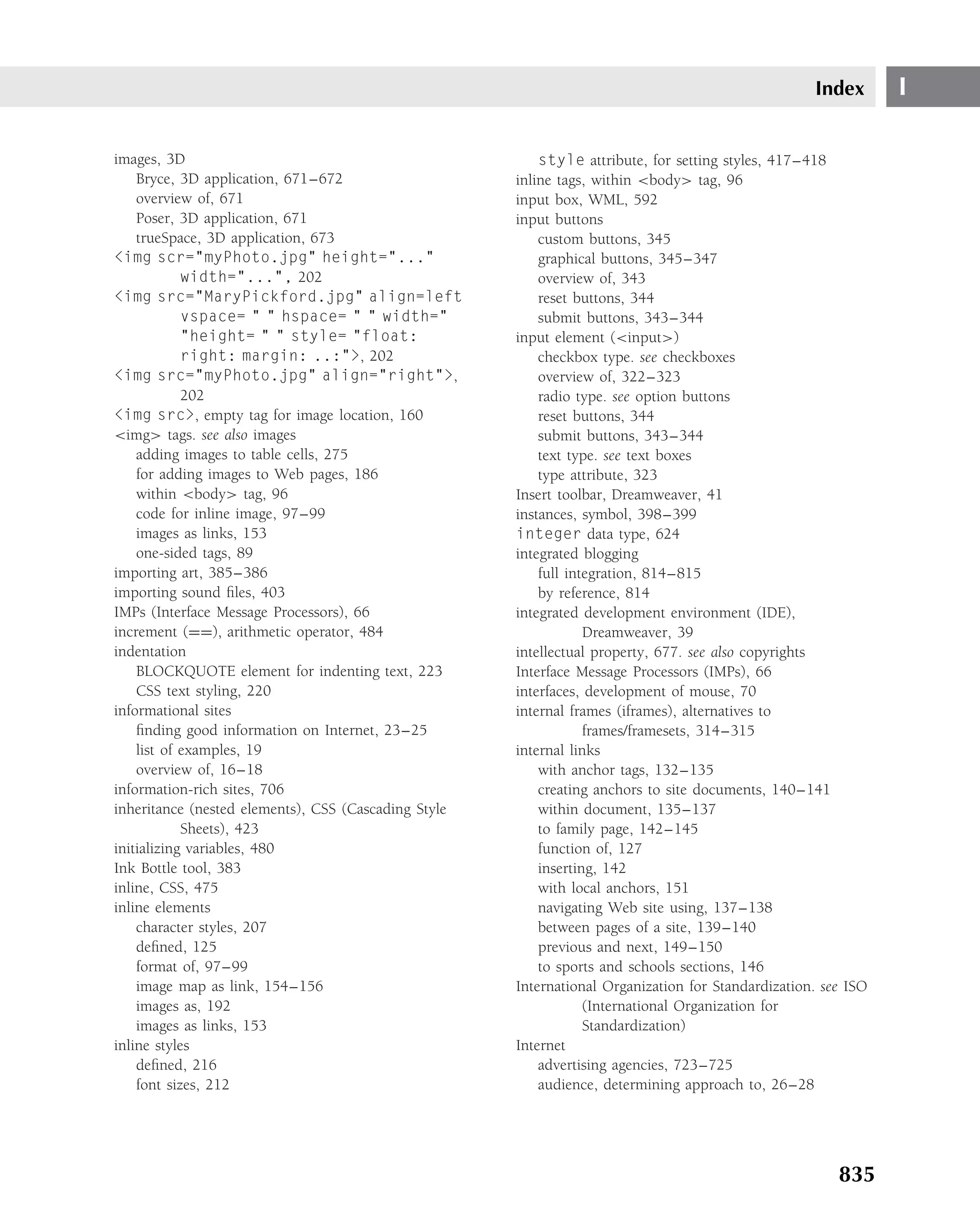

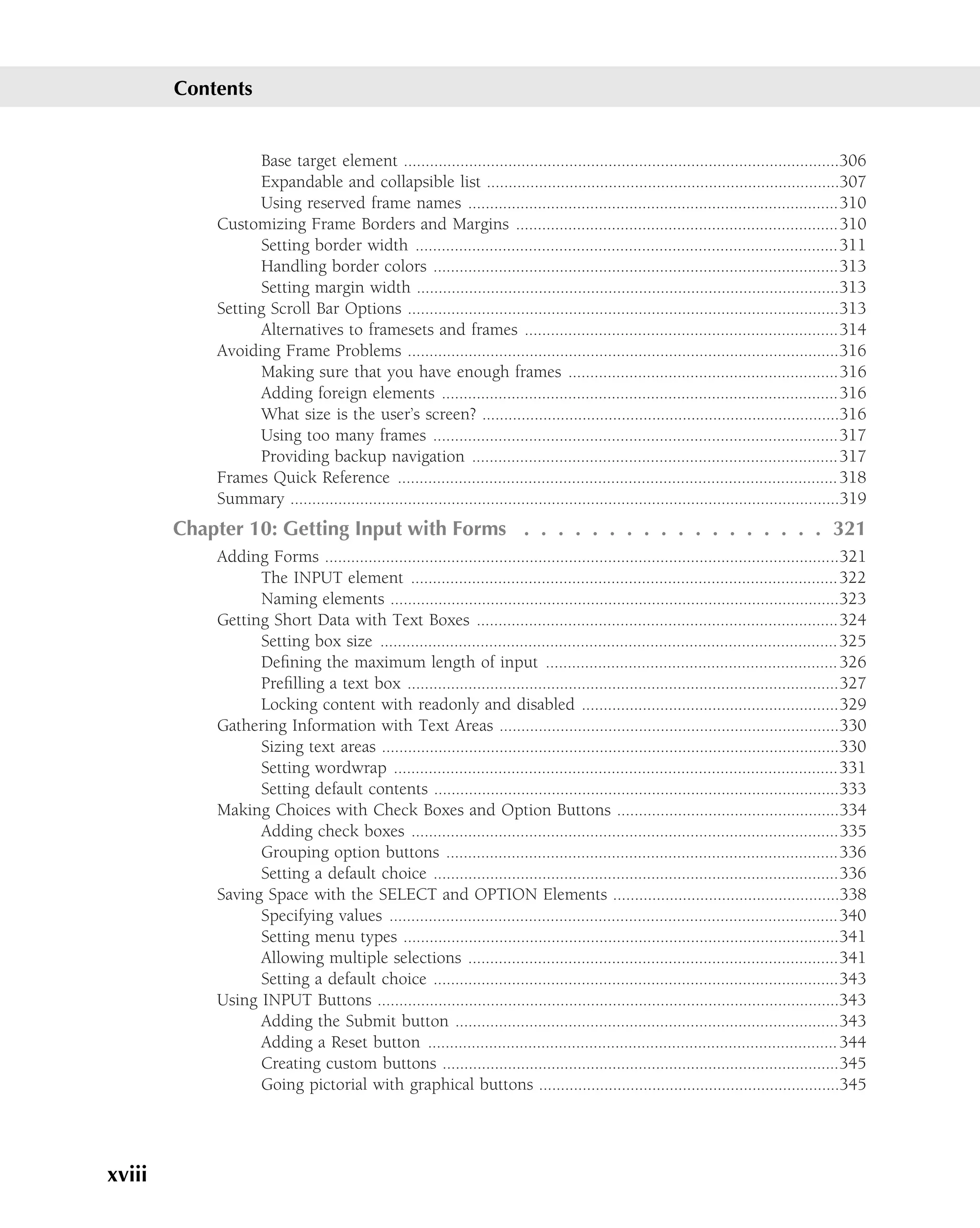

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

background-image

■ Value — ‹url› | none

■ Initial value — None

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

background-position

■ Value — [‹percentage› | ‹length›]{1,2} | [top | center | bottom] ||

[left | center | right]

■ Initial value — 0% 0%

■ Applies to — Block-level and replaced elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — Refer to the size of the element itself

background-repeat

■ Value — repeat | repeat-x | repeat-y | no-repeat

■ Initial value — repeat

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

border

■ Value — ‹border-width› || ‹border-style› || ‹color›

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

border-color

■ Value — ‹color›{1,4}

■ Initial value — The value of the color property

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

428](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-464-2048.jpg)

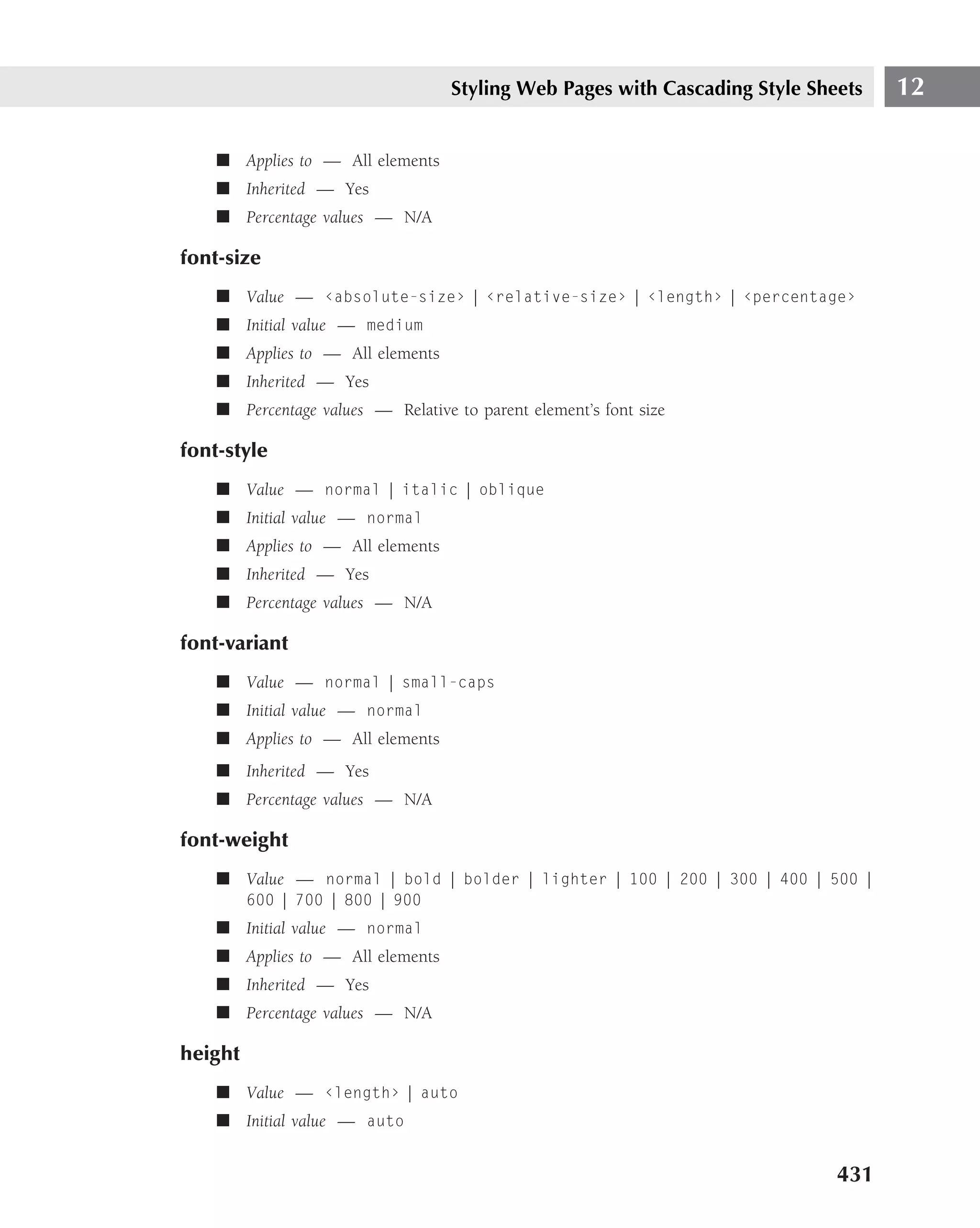

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

border-style

■ Value — None | dotted | dashed | solid | double | groove | ridge | inset

| outset

■ Initial value — None

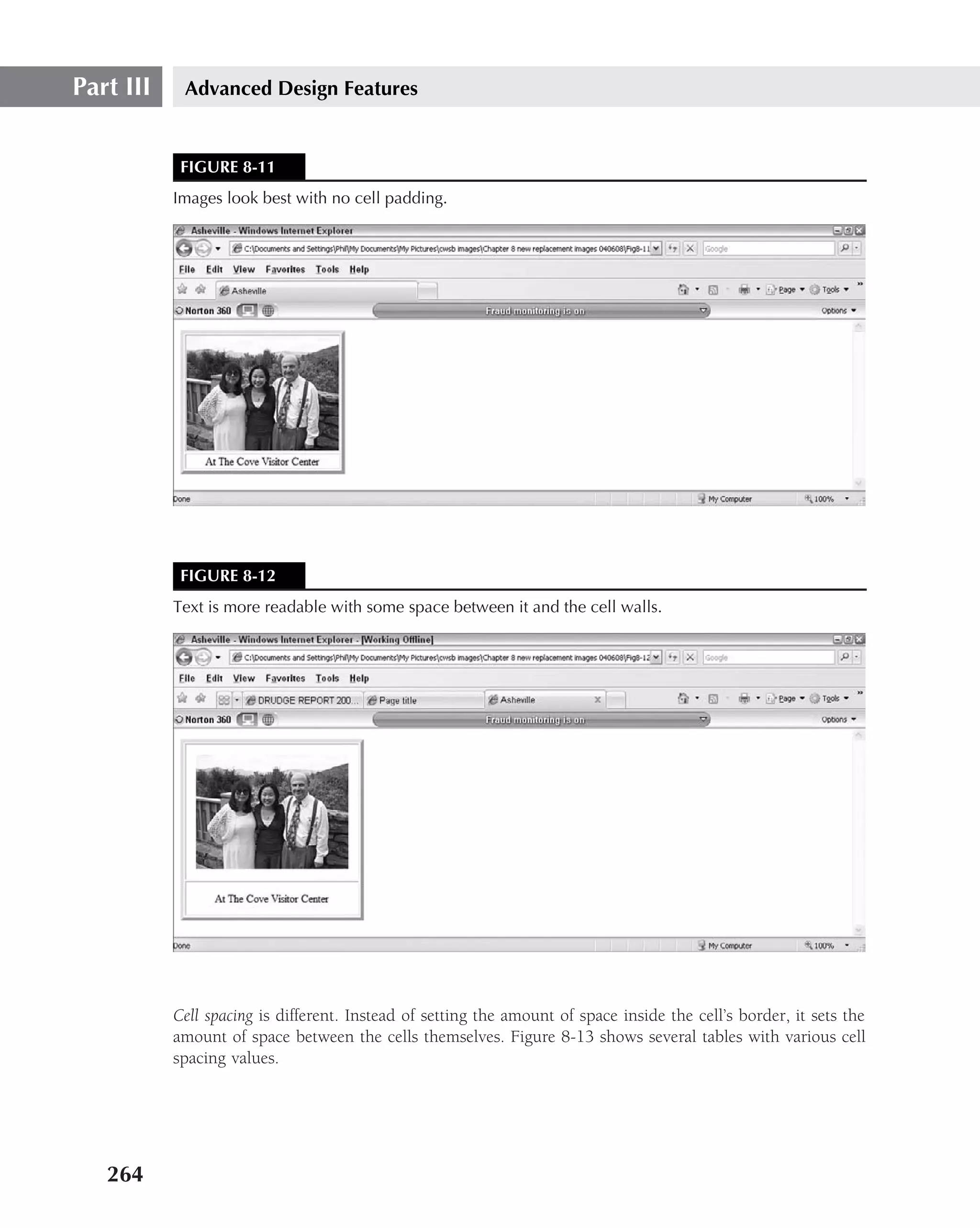

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

border-top, border-right, border-bottom, border-left

■ Value — ‹border-top-width› || ‹border-style› || ‹color›

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

border-width

■ Value — [thin | medium | thick | ‹length›]{1,4}

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

border-top-width, border-right-width, border-bottom-width,

border-left-width

■ Value — thin | medium | thick | ‹length›

■ Initial value — medium

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

clear

■ Value — none | left | right | both

■ Initial — None

■ Applies to — All elements

429](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-465-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

color

■ Value — ‹color›

■ Initial value — UA specific

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

display

■ Value — block | inline | list-item | none

■ Initial value — block

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

float

■ Value — left | right | none

■ Initial value — None

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

font

■ Value — [ ‹font-style› || ‹font-variant› || ‹font-weight› ]? ‹font-

size› [ / ‹line-height› ]? ‹font-family›

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — Allowed on ‹font-size› and ‹line-height›

font-family

■ Value — [[ ‹family-name› | ‹generic-family› ],]* [ ‹family-name› |

‹generic-family› ]

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

430](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-466-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

■ Applies to — Block-level and replaced elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — N/A

letter-spacing

■ Value — normal | ‹length›

■ Initial value — normal

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

line-height

■ Value — normal | ‹number› | ‹length› | ‹percentage›

■ Initial value — Normal

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — Relative to the font size of the element itself

list-style

■ Value — [disc | circle | square | decimal | lower-roman | upper-

roman | lower-alpha | upper-alpha | none] || [inside | outside]

|| [‹url› | none]

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — Elements with display value list-item

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

list-style-image

■ Value — ‹url› | none

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — Elements with display value list-item

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

432](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-468-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

list-style-position

■ Value — inside | outside

■ Initial value — outside

■ Applies to — Elements with display value list-item

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

list-style-type

■ Value — disc | circle | square | decimal | lower-roman | upper-roman |

lower-alpha | upper-alpha | none

■ Initial value — disc

■ Applies to — Elements with display value list-item

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

margin

■ Value — [ ‹length› | ‹percentage› | auto ] {1,4}

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — Refer to width of closest block-level ancestor

margin-top, margin-right, margin-bottom, margin-left

■ Value — ‹length› | ‹percentage› | auto

■ Initial value — 0

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — Refer to width of the closest block-level ancestor

padding

■ Value — [ ‹length› | ‹percentage› ] {1,4}

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

433](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-469-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — Refer to width of closest block-level ancestor

padding-top, padding-right, padding-bottom, padding-left

■ Value — ‹length› | ‹percentage›

■ Initial value — 0

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentage values — Refer to width of closest block-level ancestor

text-align

■ Value — left | right | center | justify

■ Initial value — UA specific

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited value — Yes

■ Percentage values — N/A

text-decoration

■ Value — none | [ underline || overline || line-through || blink ]

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All elements

■ Inherited — No, but elements should match their parent

■ Percentage values — N/A

text-indent

■ Value — ‹length› | ‹percentage›

■ Initial value — 0

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentage values — Refer to parent element’s width

text-transform

■ Value — capitalize | uppercase | lowercase | none

■ Initial value — none

434](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-470-2048.jpg)

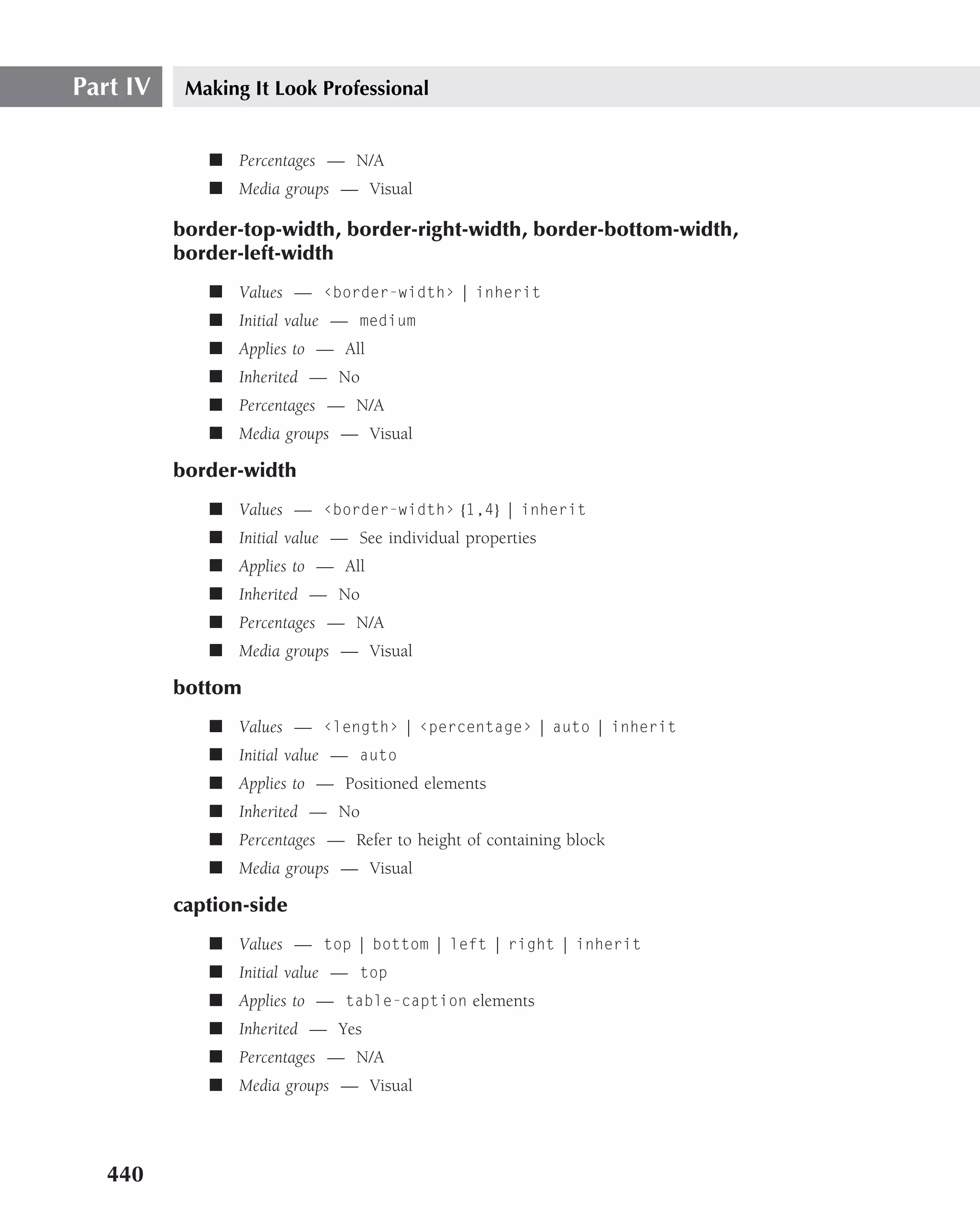

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

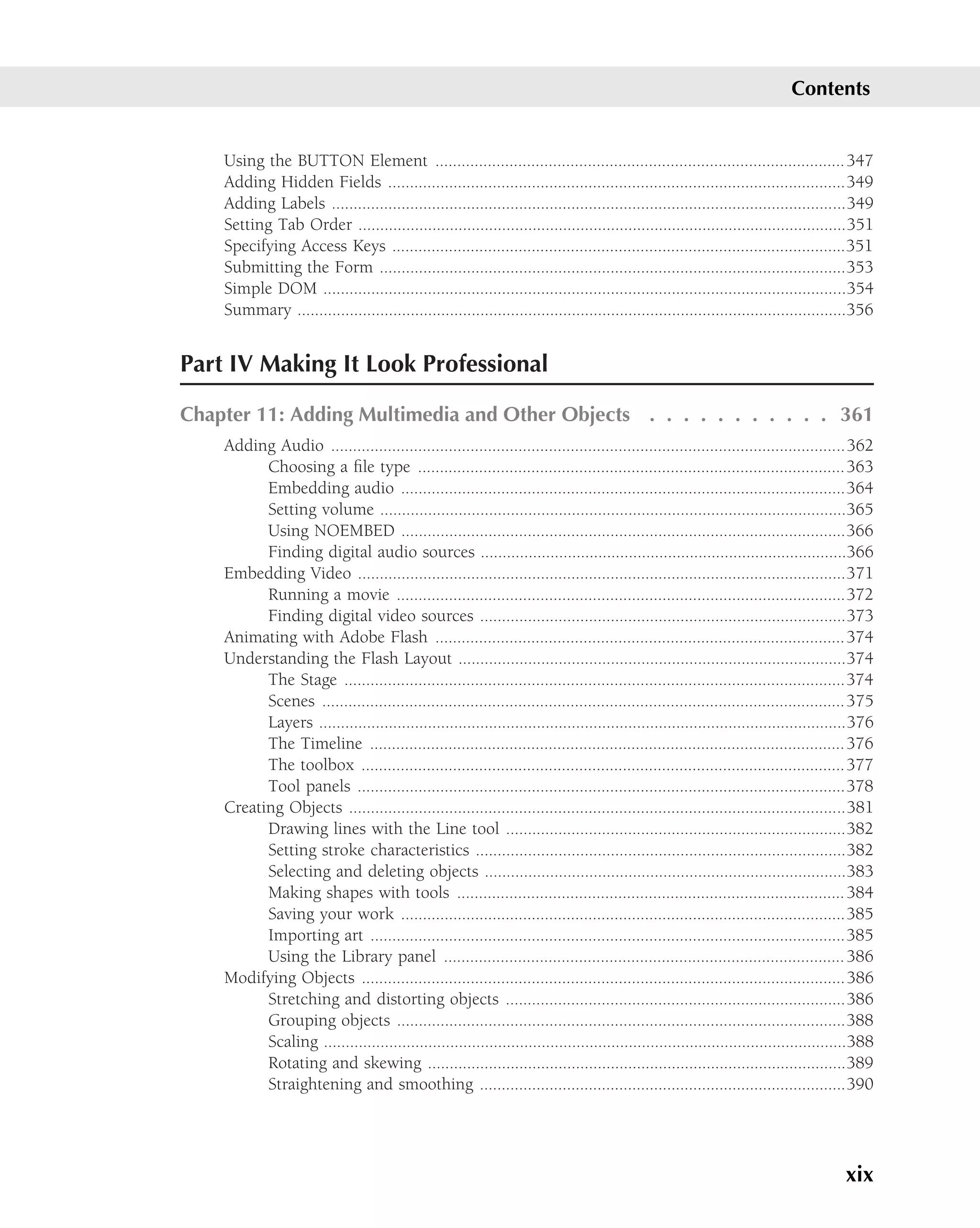

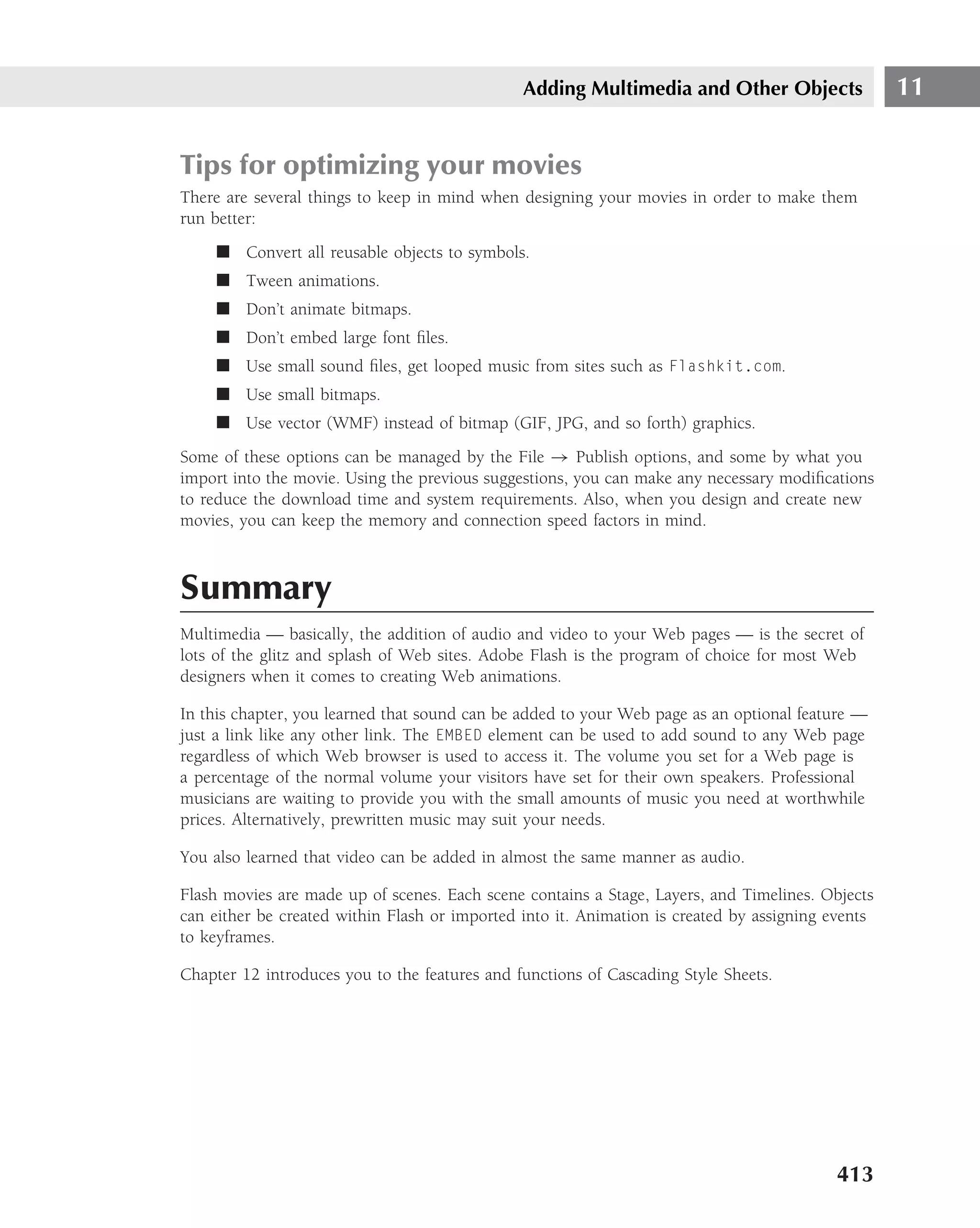

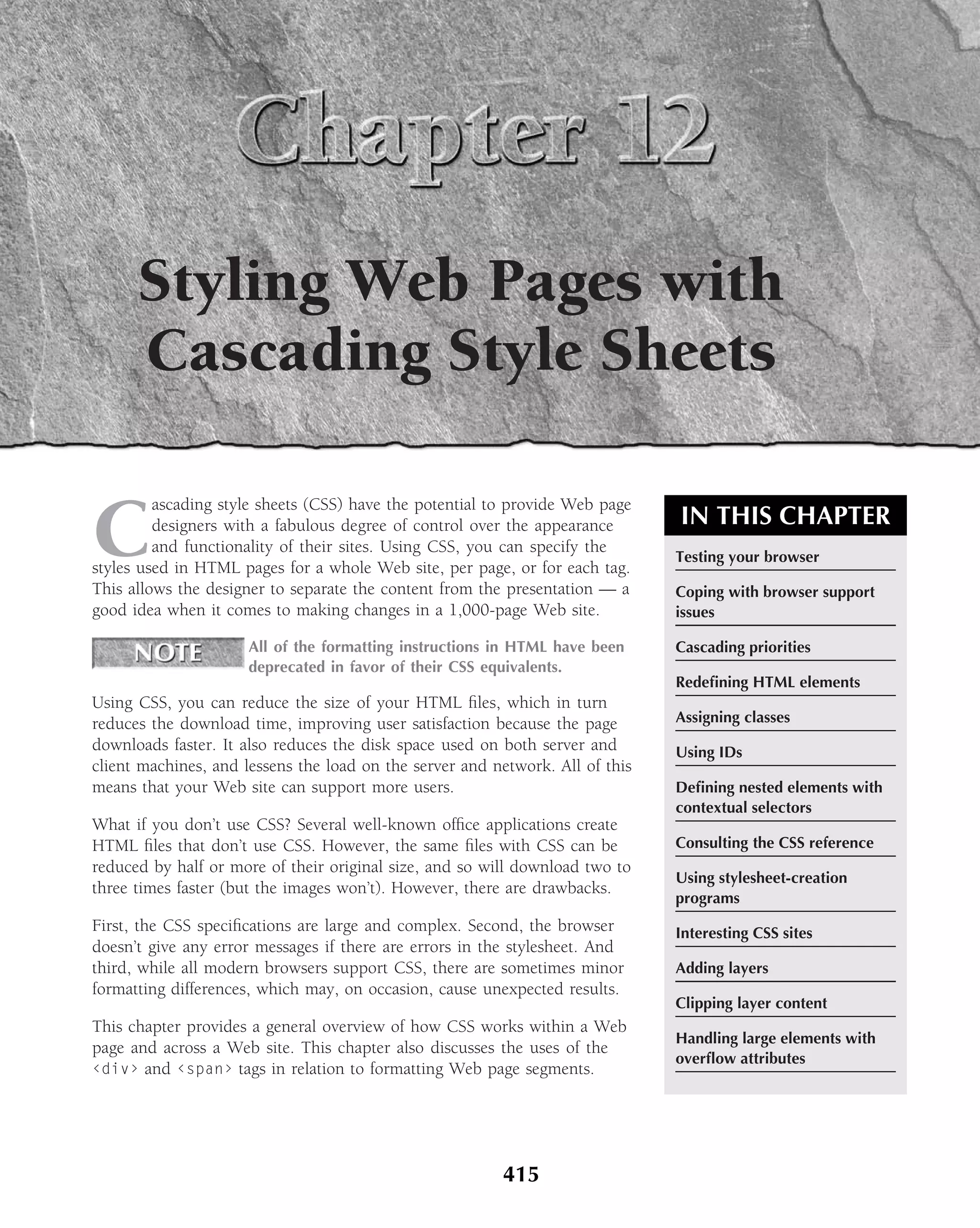

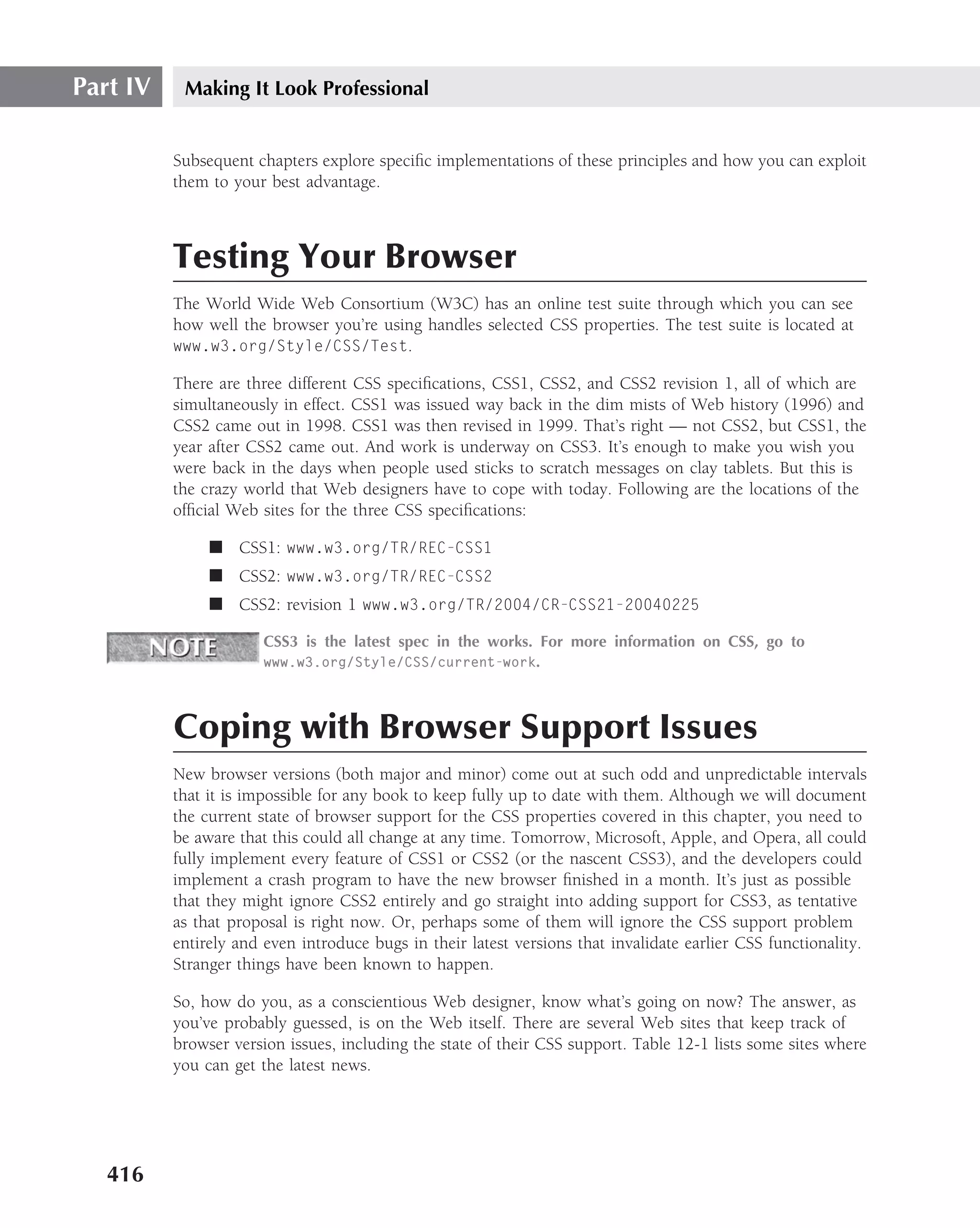

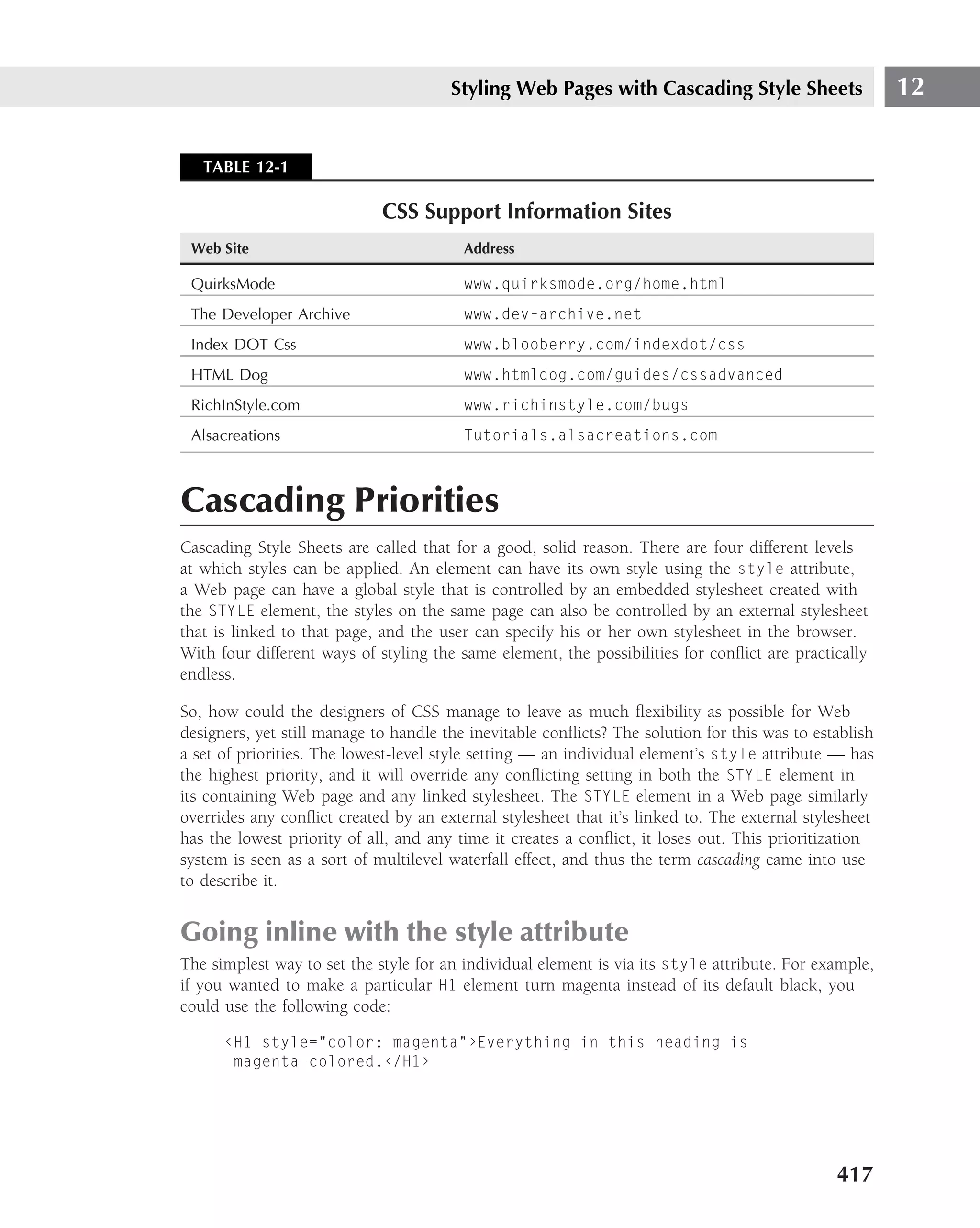

specification is www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2. Although the specification carries no specific copy-

right notice, we assume that the usual requirement of adding the following notice to information

taken from W3C documents still applies:

Copyright © World Wide Web Consortium, (Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et en Automatique, Keio University).

All Rights Reserved.

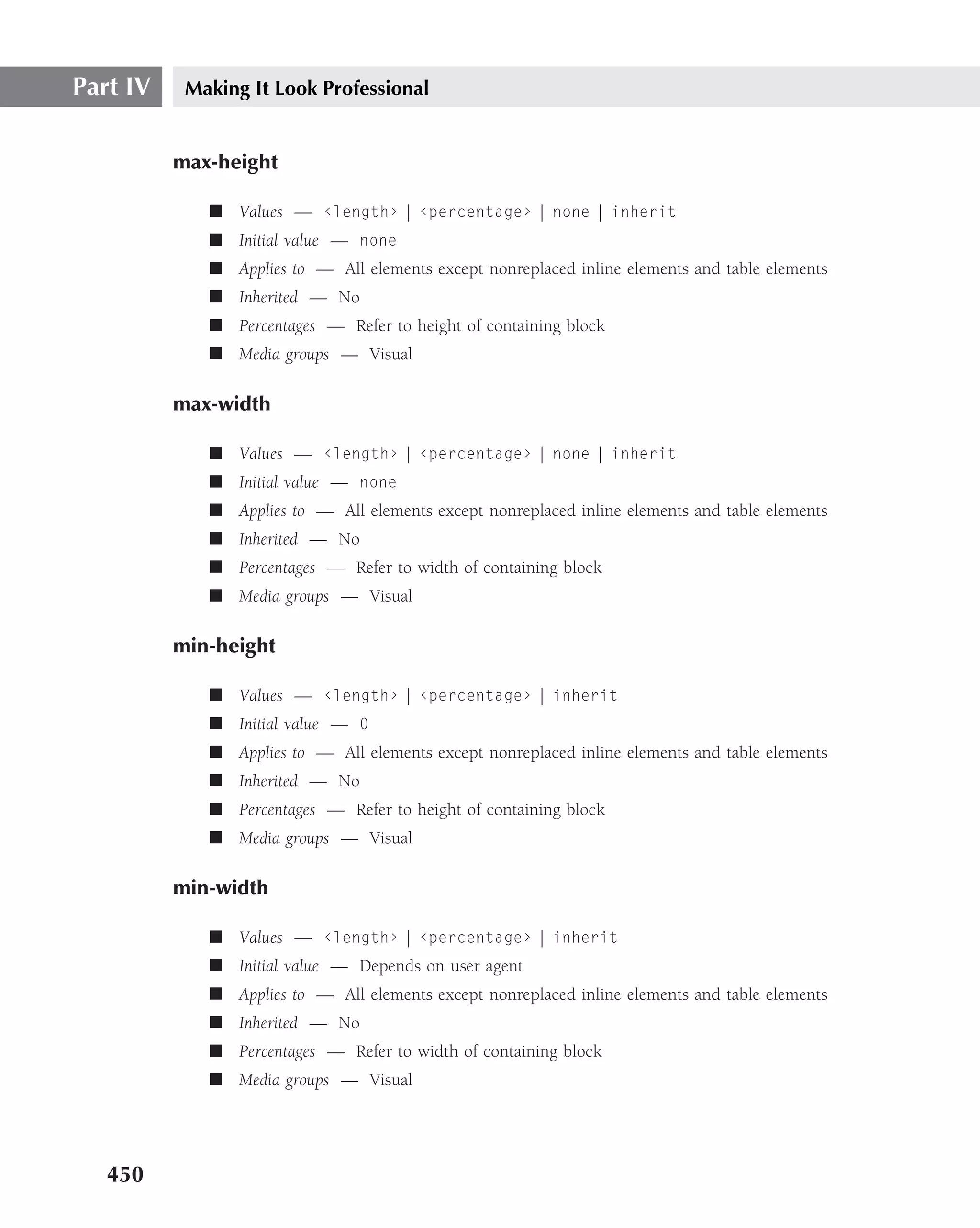

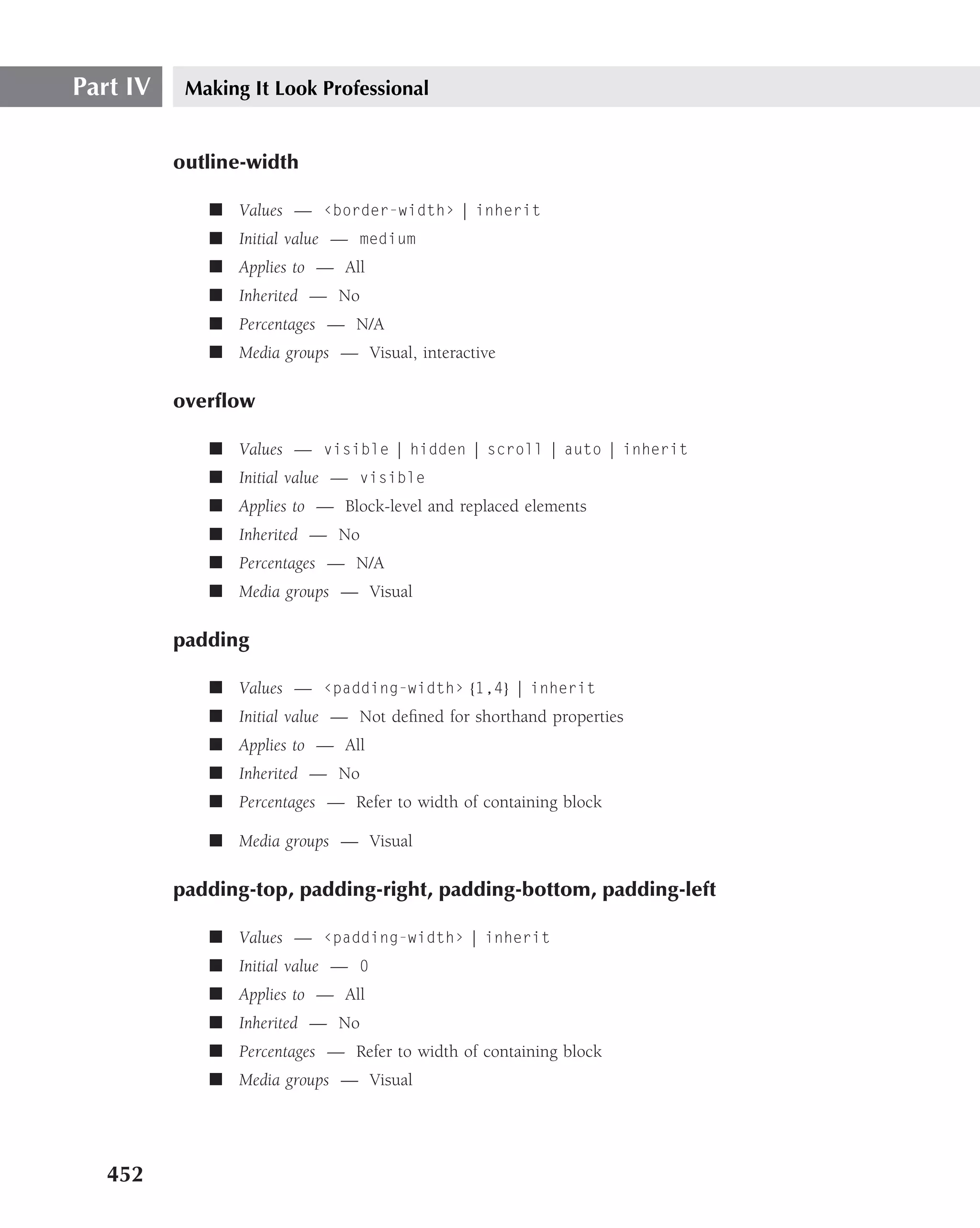

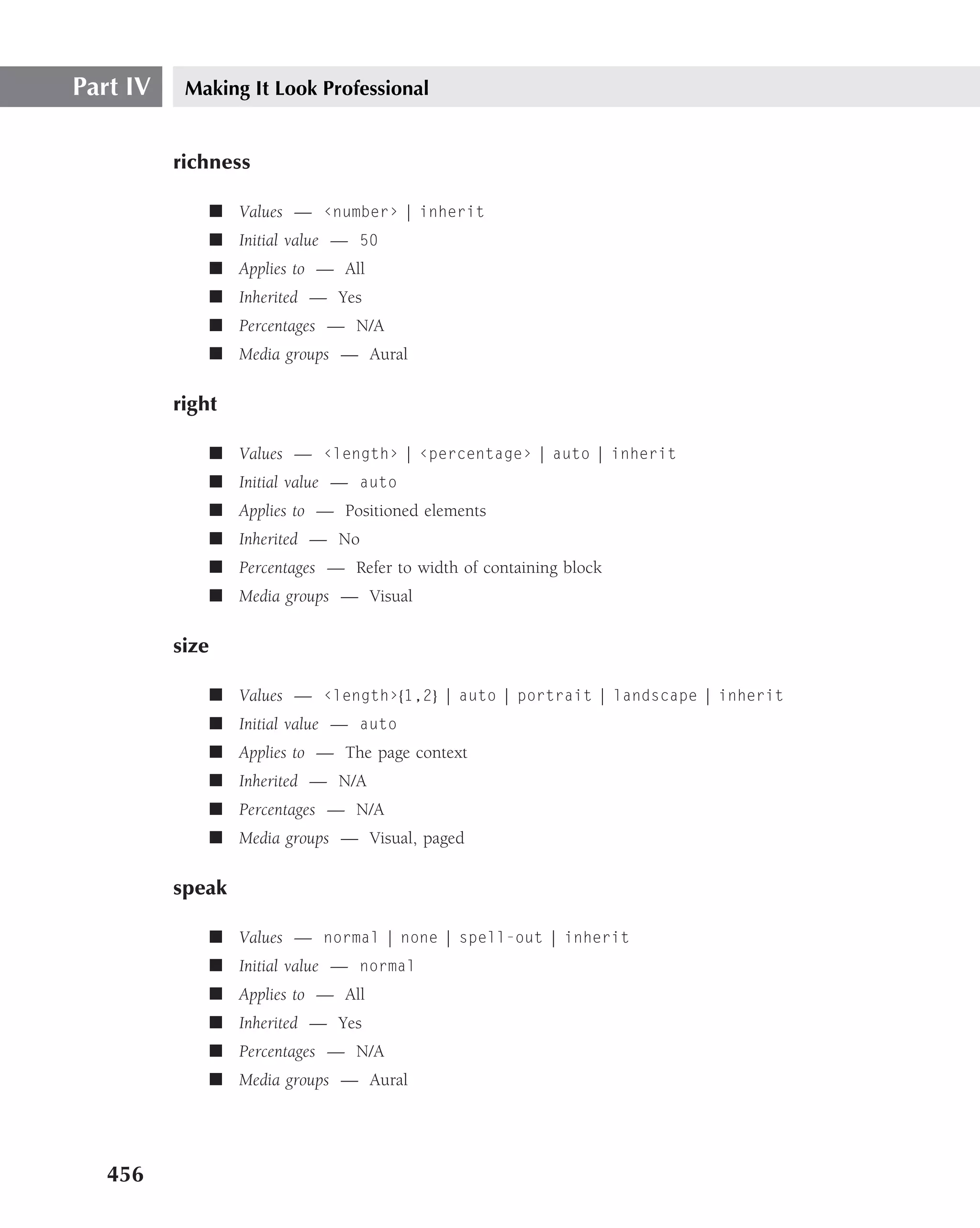

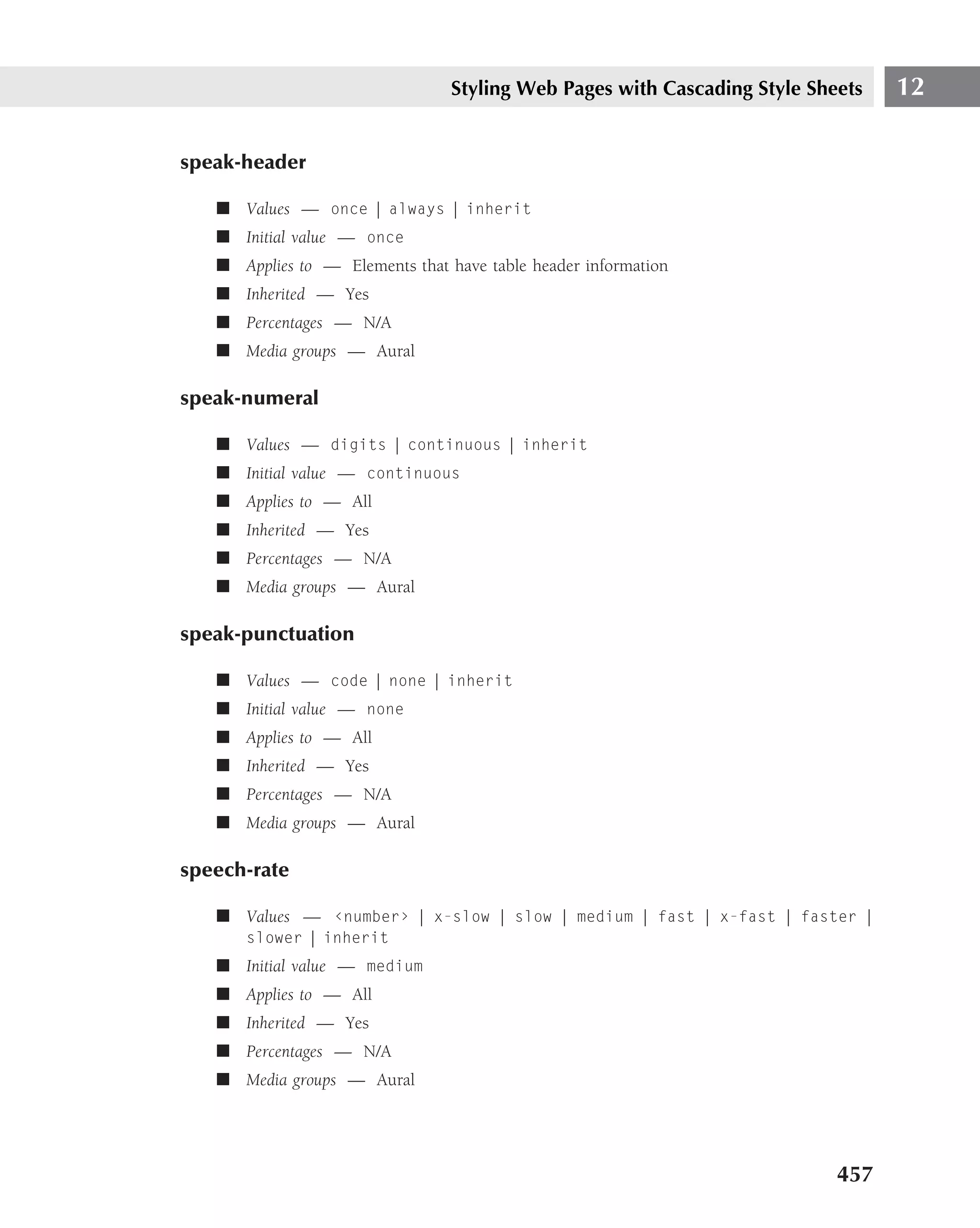

The properties in the following listing are specified by name (in alphabetical order), and then the

following information is presented:

■ Values — Shows all possible values that can be used with this property.

■ Initial value — Shows the default value if none is specified.

■ Applies to — Shows the elements the property can be applied to.

■ Inherited — Shows if the property can be inherited.

■ Percentages — Shows how percentages are handled.

■ Media groups — Shows which media group (visual, aural, print, and so on) the property

is intended for.

Following is a breakdown of CSS2 properties.

azimuth

■ Values — ‹angle› | [[ left-side | far-left | left | center-left | center

| center-right | right | far-right | right-side ] || behind ] | leftwards

| rightwards | inherit

■ Initial value — center

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

background

■ Values — [‘background-color’ || ‘background-image’ || ‘background-

repeat’ || ‘background-attachment’ || ‘background-position’] | inherit

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — Allowed on background-position

■ Media groups — Visual

436](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-472-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

background-attachment

■ Values — scroll | fixed | inherit

■ Initial value — scroll

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

background-color

■ Values — ‹color› | transparent | inherit

■ Initial value — transparent

■ Applies to — All

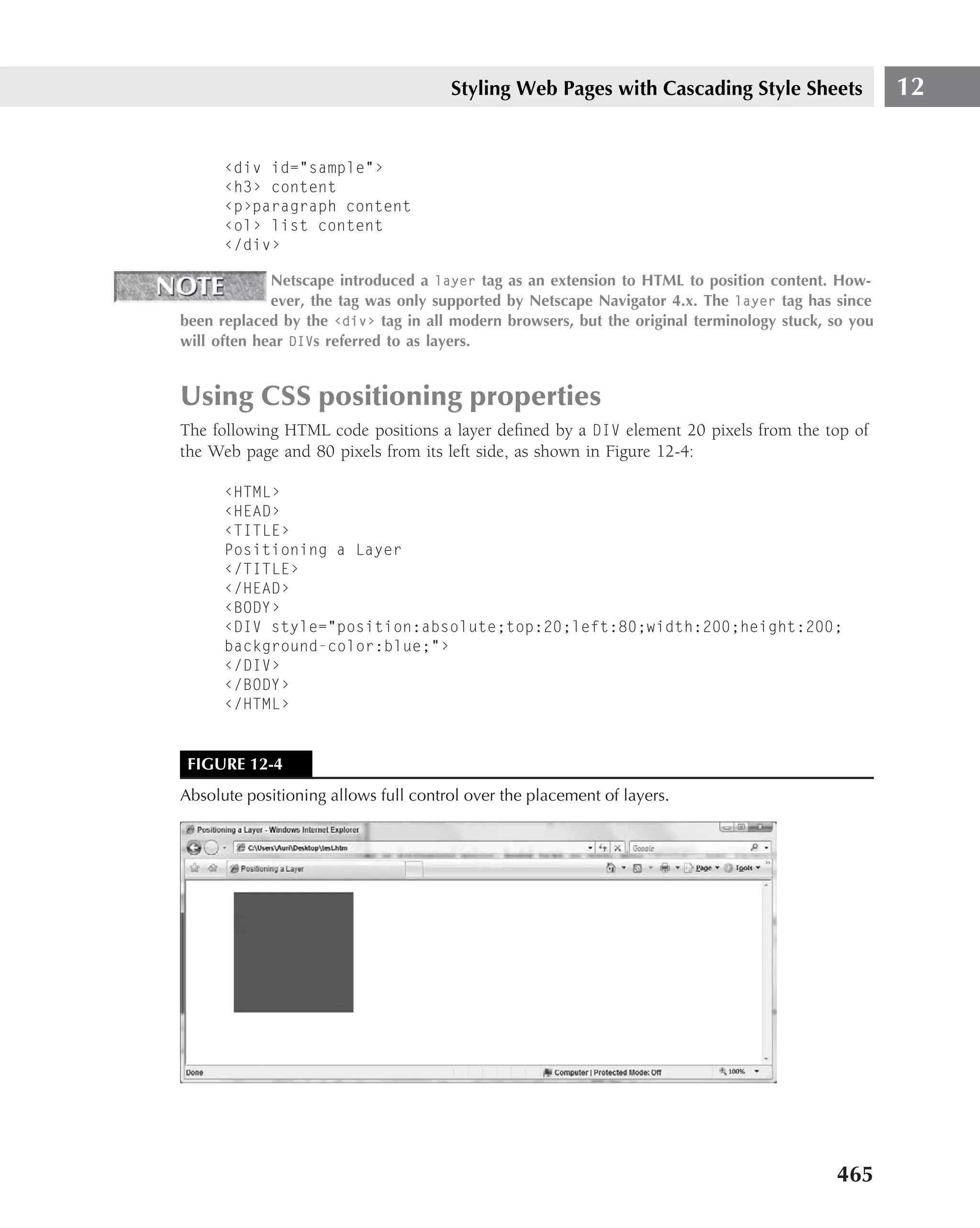

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

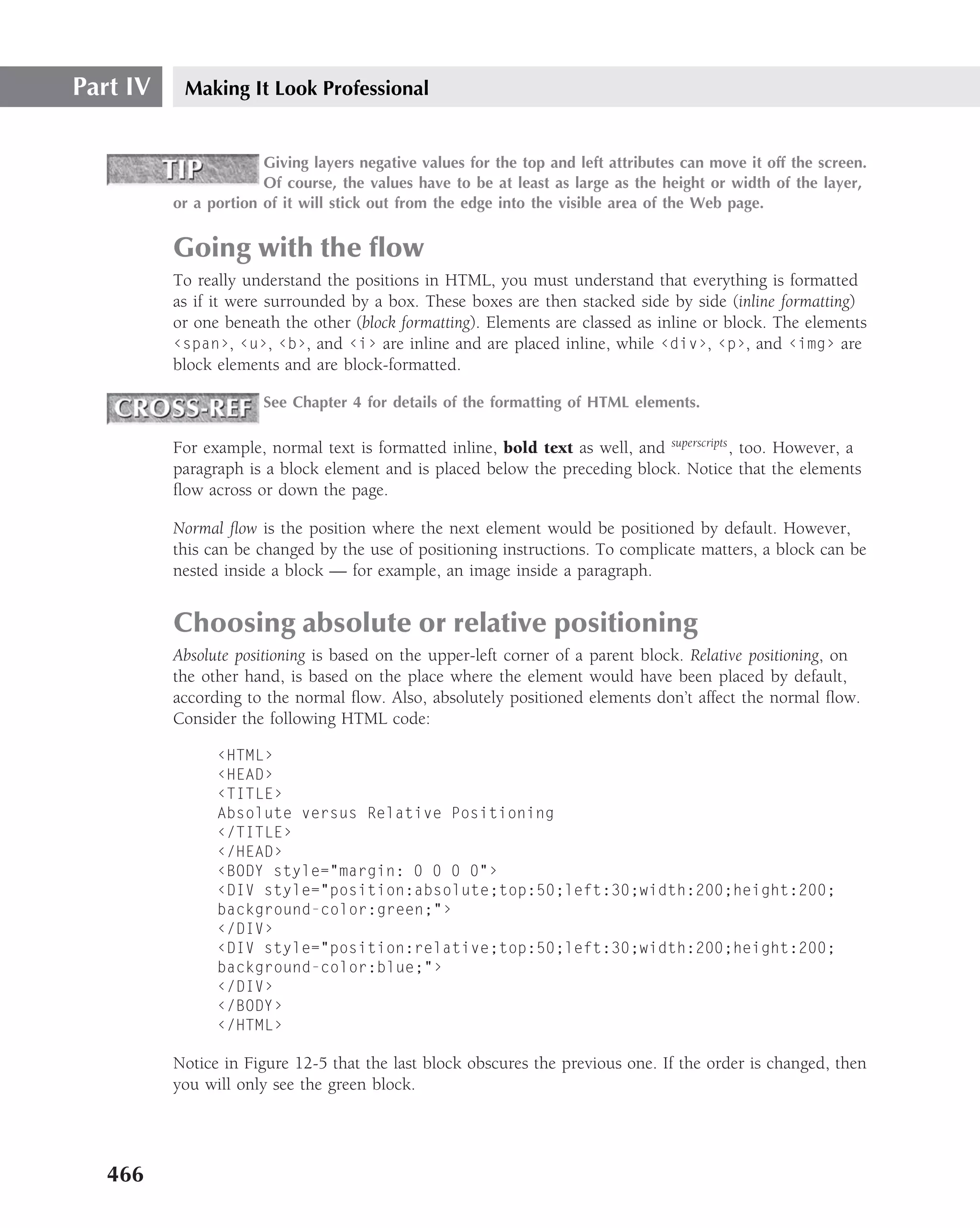

background-image

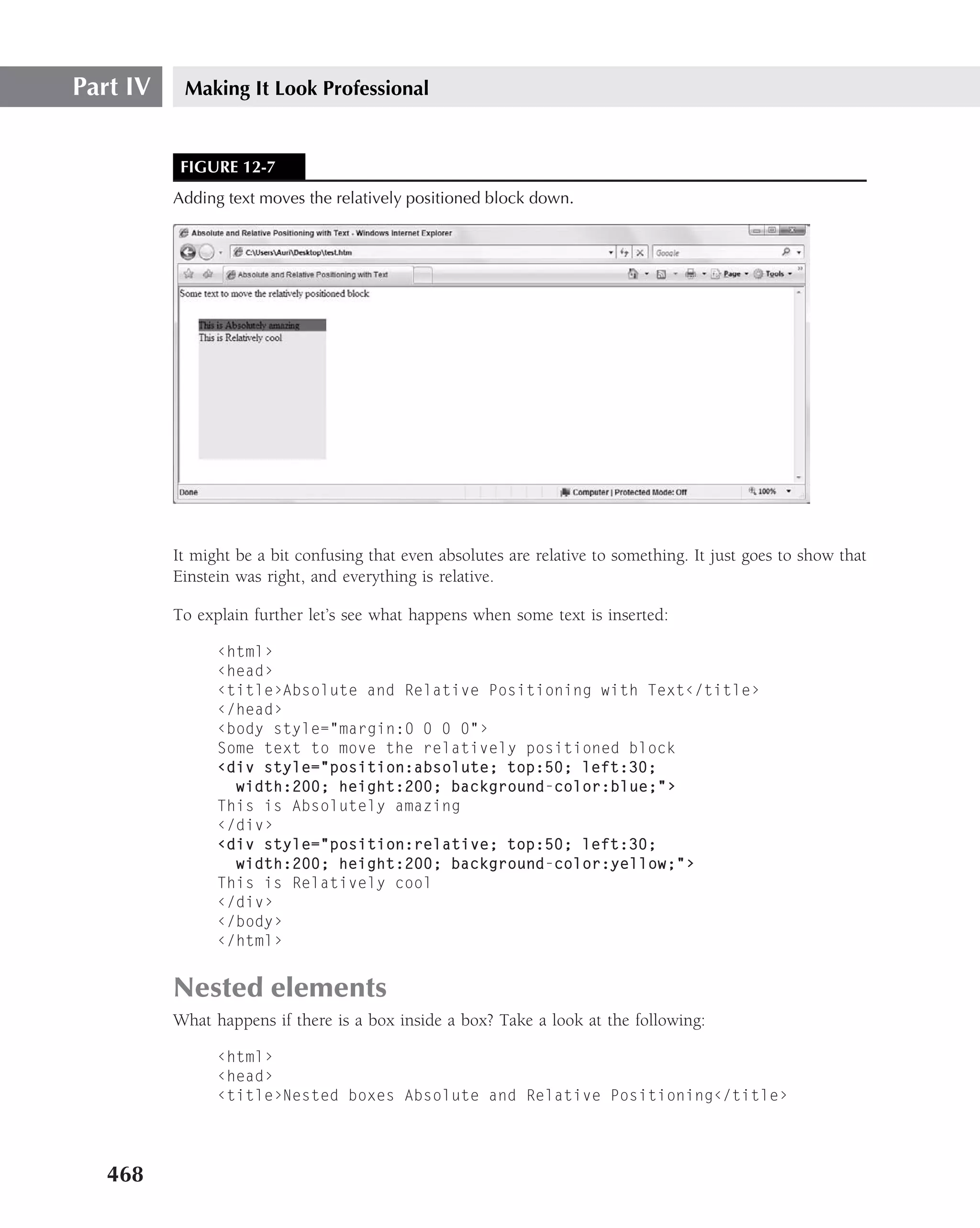

■ Values — ‹uri› | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

background-position

■ Values — [ [‹percentage› | ‹length› ] {1,2} | [ [top | center | bottom] ||

[left | center | right] ] ] | inherit

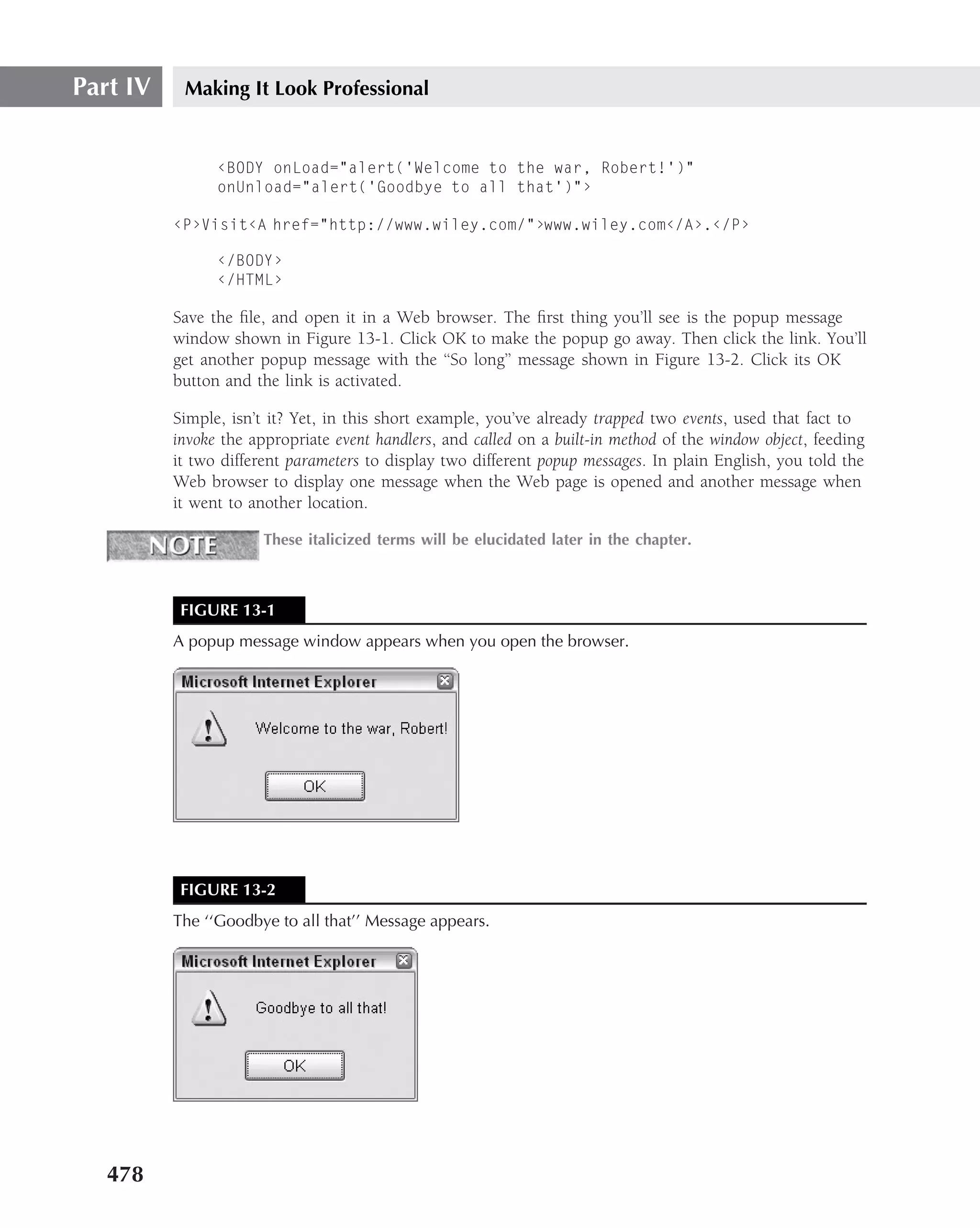

■ Initial value — 0% 0%

■ Applies to — Block-level and replaced elements

■ Inherited — No

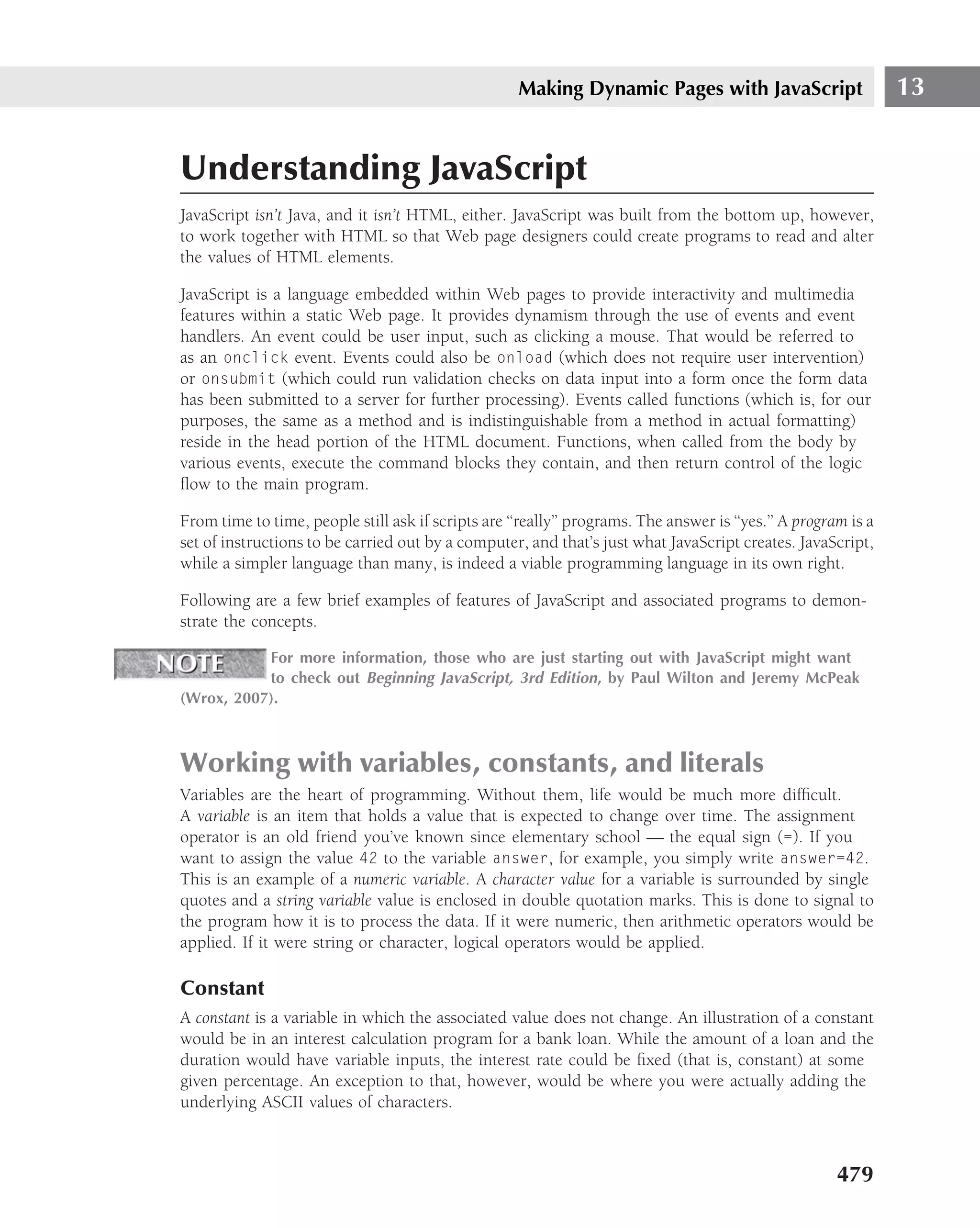

■ Percentages — Refer to the size of the box itself

■ Media groups — Visual

437](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-473-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

background-repeat

■ Values — repeat | repeat-x | repeat-y | no-repeat | inherit

■ Initial value — repeat

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border

■ Values — [ ‘border-width’ || ‘border-style’ || ‹color› ] | inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-collapse

■ Values — collapse | separate | inherit

■ Initial value — collapse

■ Applies to — table and inline-table elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-color

■ Values — ‹color›{1,4} | transparent | inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-spacing

■ Values — ‹length› ‹length›? | inherit

■ Initial value — 0

438](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-474-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

■ Applies to — table and inline-table elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-style

■ Values — ‹border-style› {1,4} | inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-top, border-right, border-bottom, border-left

■ Values — [ ‘border-top-width’ || ‘border-style’ || ‹color› ] | inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-top-color, border-right-color, border-bottom-color,

border-left-color

■ Values — ‹color› | inherit

■ Initial value — The value of the color property

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

border-top-style, border-right-style, border-bottom-style, border-left-style

■ Values — ‹border-style› | inherit

■ Initial value — None

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

439](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-475-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

clear

■ Values — none | left | right | both | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

clip

■ Values — ‹shape› | auto | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

■ Applies to — Block-level and replaced elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

color

■ Values — ‹color› | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

content

■ Values — [ ‹string› | ‹uri› | ‹counter› | attr(X) | open-quote | close-

quote | no-open-quote | no-close-quote ]+ | inherit

■ Initial value — Empty string

■ Applies to — :before and :after pseudo-elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — All

441](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-477-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

counter-increment

■ Values — [ ‹identifier› ‹integer›?]+ | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — All

counter-reset

■ Values — [ ‹identifier› ‹integer›?]+ | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — All

cue

■ Values — [ ‘cue-before’ || ‘cue-after’ ] | inherit

■ Initial value — XX

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

cue-after

■ Values — ‹uri› | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

442](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-478-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

cue-before

■ Values — ‹uri› | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

cursor

■ Values — [ [‹uri› ,]* [ auto | crosshair | default | pointer | move |

e-resize | ne-resize | nw-resize | n-resize | se-resize | sw-resize |

s-resize | w-resize| text | wait | help ] ] | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, interactive

direction

■ Values — ltr | rtl | inherit

■ Initial value — ltr

■ Applies to — All elements, but see prose

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

The cautionary message, ’’but see prose,’’ basically tells the author or user to ignore

the properties in author and user stylesheets.

display

■ Values — inline | block | list-item | run-in | compact | marker | table

| inline-table | table-row-group | table-header-group | table-footer-

group | table-row | table-column-group | table-column | table-cell |

table-caption | none | inherit

■ Initial value — inline

■ Applies to — All

443](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-479-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — All

elevation

■ Values — ‹angle› | below | level | above | higher | lower | inherit

■ Initial value — level

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

empty-cells

■ Values — show | hide | inherit

■ Initial value — show

■ Applies to — table-cell elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

float

■ Values — left | right | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All but positioned elements and generated content

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

font

■ Values — [ [ ‘font-style’ || ‘font-variant’ || ‘font-weight’ ]? ‘font-

size’ [ / ‘line-height’ ]? ‘font-family’ ] | caption | icon | menu |

message-box | small-caption | status-bar | inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

444](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-480-2048.jpg)

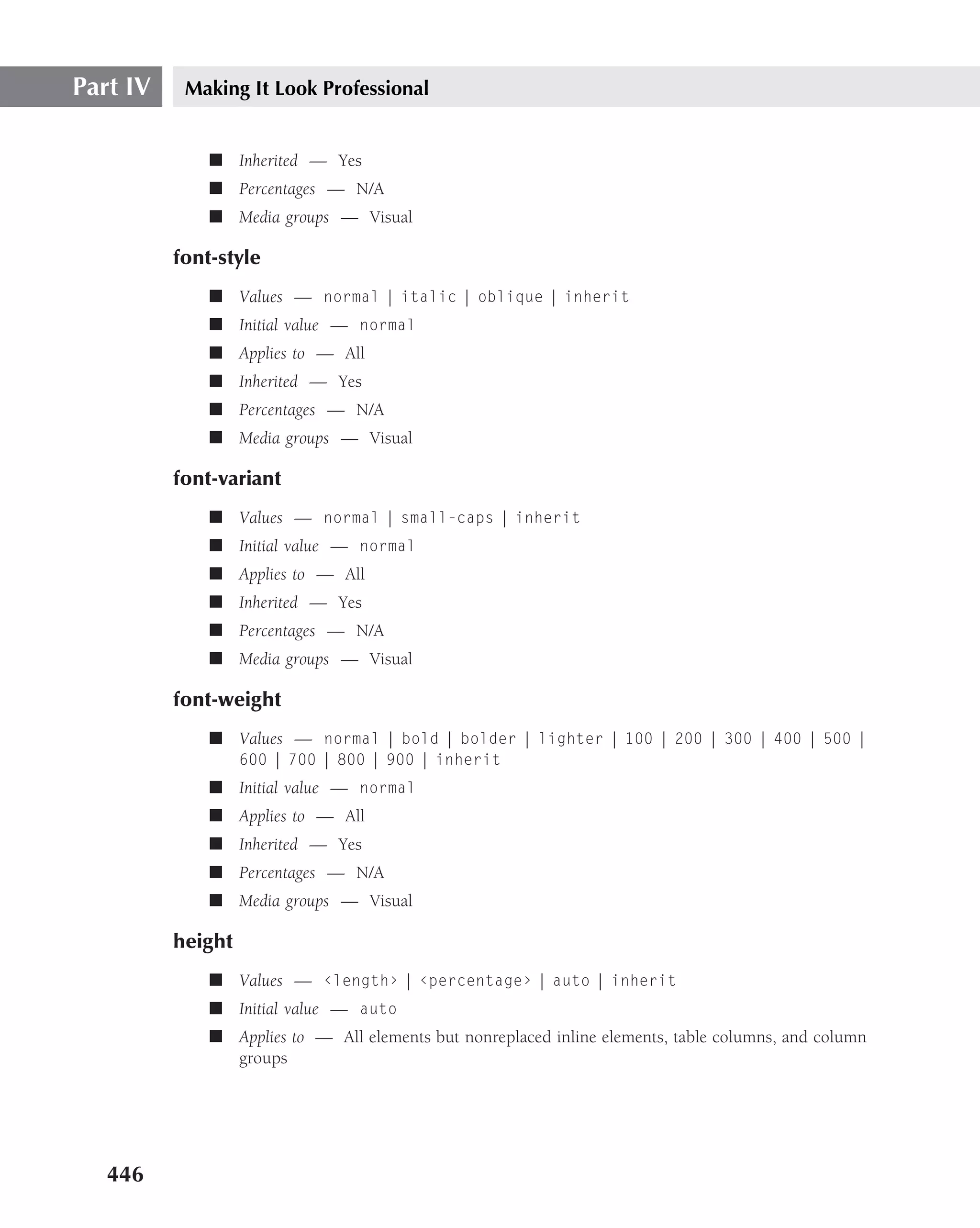

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — Allowed on font-size and line-height

■ Media groups — Visual

font-family

■ Values — [[ ‹family-name› | ‹generic-family› ],]* [ ‹family-name› |

‹generic-family› ] | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

font-size

■ Values — ‹absolute-size› | ‹relative-size› | ‹length› | ‹percentage› |

inherit

■ Initial value — medium

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes, the computed value is inherited

■ Percentages — Refer to parent element’s font size

■ Media groups — Visual

font-size-adjust

■ Values — ‹number› | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

font-stretch

■ Values — normal | wider | narrower | ultra-condensed | extra-condensed

| condensed | semi-condensed | semi-expanded | expanded | extra-

expanded | ultra-expanded | inherit

■ Initial value — normal

■ Applies to — All

445](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-481-2048.jpg)

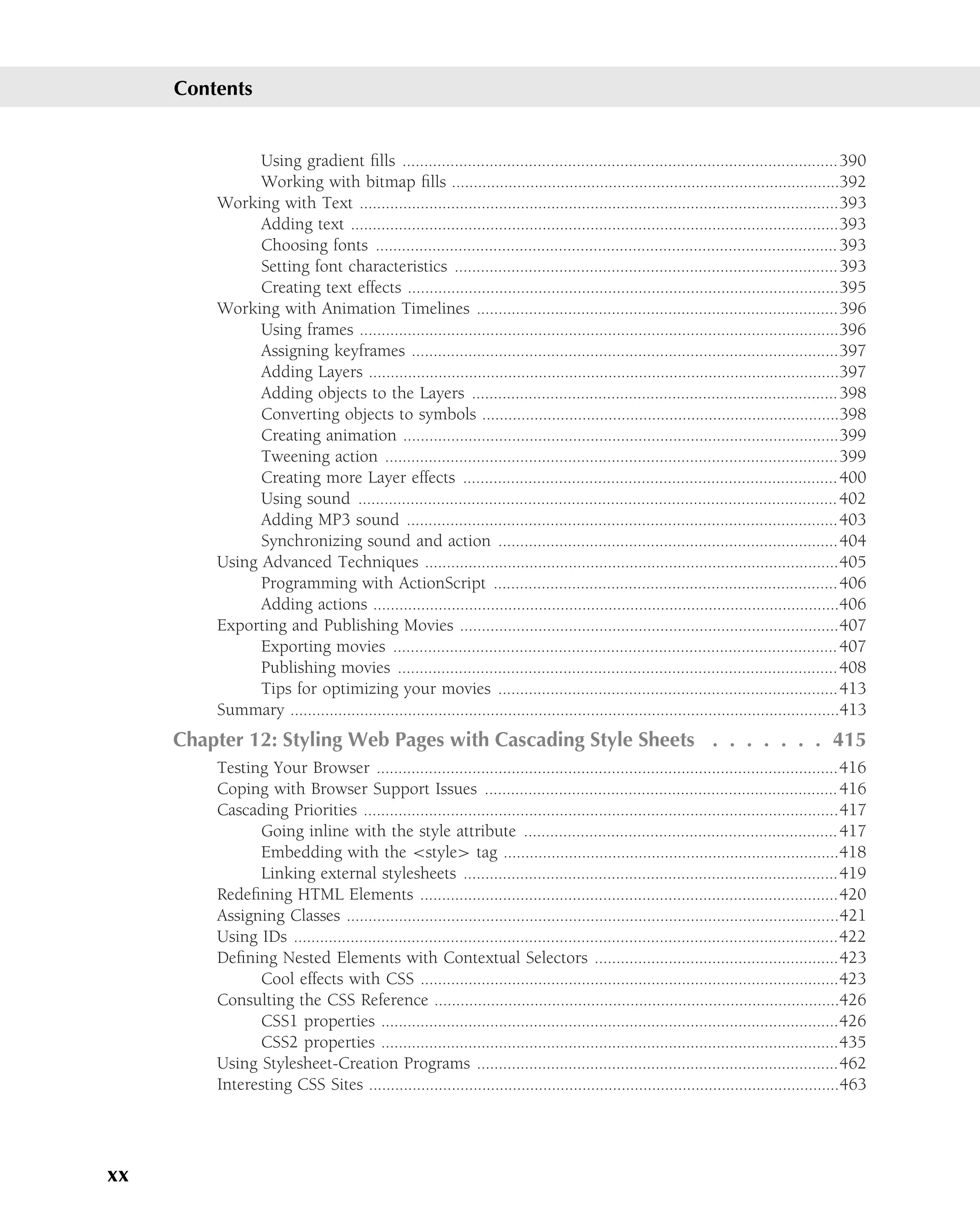

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — See prose

■ Media groups — Visual

The cautionary message, ’’but see prose,’’ basically tells the author or user to ignore

the properties in author and user stylesheets.

left

■ Values — ‹length› | ‹percentage› | auto | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

■ Applies to — Positioned elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — Refer to width of containing block

■ Media groups — Visual

letter-spacing

■ Values — normal | ‹length› | inherit

■ Initial value — normal

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

line-height

■ Values — normal | ‹number› | ‹length› | ‹percentage› | inherit

■ Initial value — normal

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — Refer to the font size of the element itself

■ Media groups — Visual

list-style

■ Values — [ ‘list-style-type’ || ‘list-style-position’ || ‘list-style-

image’ ] | inherit

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

447](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-483-2048.jpg)

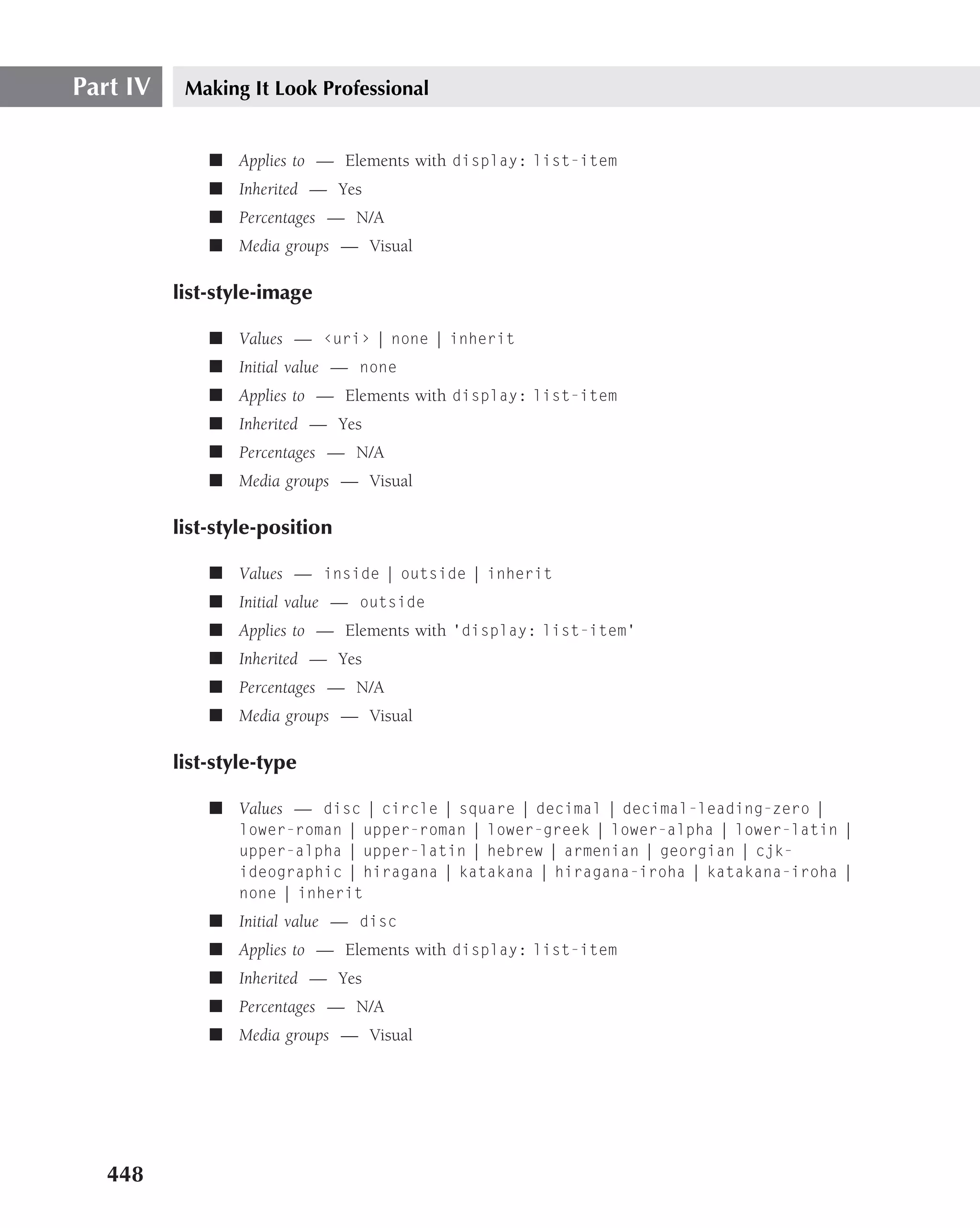

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

margin

■ Values — ‹margin-width› {1,4} | inherit

■ Initial value — Not defined for shorthand properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — Refer to width of containing block

■ Media groups — Visual

margin-top, margin-right, margin-bottom, margin-left

■ Values — ‹margin-width› | inherit

■ Initial value — 0

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — Refer to width of containing block

■ Media groups — Visual

marker-offset

■ Values — ‹length› | auto | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

■ Applies to — Elements with display: marker

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

marks

■ Values — [ crop || cross ] | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — Page context

■ Inherited — N/A

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, paged

449](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-485-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

orphans

■ Values — ‹integer› | inherit

■ Initial value — 2

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, paged

outline

■ Values — [ ‘outline-color’ || ‘outline-style’ || ‘outline-width’ ]

| inherit

■ Initial value — See individual properties

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, interactive

outline-color

■ Values — ‹color› | invert | inherit

■ Initial value — invert

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, interactive

outline-style

■ Values — ‹border-style› | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, interactive

451](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-487-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

pause

■ Values — [ [‹time› | ‹percentage›]{1,2} ] | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — See descriptions of pause-after and pause-before

■ Media groups — Aural

pause-after

■ Values — ‹time› | ‹percentage› | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — See prose

■ Media groups — Aural

The cautionary message, ’’but see prose,’’ basically tells the author or user to ignore

the properties in author and user stylesheets.

pause-before

■ Values — ‹time› | ‹percentage› | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — See prose

■ Media groups — Aural

pitch

■ Values — ‹frequency› | x-low | low | medium | high | x-high | inherit

■ Initial value — medium

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

454](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-490-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

pitch-range

■ Values — ‹number› | inherit

■ Initial value — 50

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

play-during

■ Values — ‹uri› mix? repeat? | auto | none | inherit

■ Initial value — Auto

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

position

■ Values — static | relative | absolute | fixed | inherit

■ Initial value — static

■ Applies to — All elements, but not to generated content

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

quotes

■ Values — [‹string› ‹string›]+ | none | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

455](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-491-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

stress

■ Values — ‹number› | inherit

■ Initial value — 50

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

table-layout

■ Values — auto | fixed | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

■ Applies to — table and inline-table elements

■ Inherited — No

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

text-align

■ Values — left | right | center | justify | ‹string› | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent and writing direction

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

text-decoration

■ Values — none | [ underline || overline || line-through || blink ]

| inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No (see prose)

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

458](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-494-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

The cautionary message, ‘‘see prose,’’ refers to the distinction between inline and

block level when using this feature. All descendants of element inherit specified

text feature.

text-indent

■ Values — ‹length› | ‹percentage› | inherit

■ Initial value — 0

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — Refer to width of containing block

■ Media groups — Visual

text-shadow

■ Values — none | [‹color› || ‹length› ‹length› ‹length›? ,]* [‹color› ||

‹length› ‹length› ‹length›?] | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — No (see prose)

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

The cautionary message, ‘‘see prose,’’ refers to the distinction between inline and

block level when using this feature. All descendants of element inherit specified

text feature.

text-transform

■ Values — capitalize | uppercase | lowercase | none | inherit

■ Initial value — none

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

top

■ Values — ‹length› | ‹percentage› | auto | inherit

■ Initial value — auto

459](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-495-2048.jpg)

![Styling Web Pages with Cascading Style Sheets 12

voice-family

■ Values — [[ ‹specific-voice› | ‹generic-voice› ],]* [ ‹specific-voice›

| ‹generic-voice› ] | inherit

■ Initial value — Depends on user agent

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Aural

volume

■ Values — ‹number› | ‹percentage› | silent | x-soft | soft | medium | loud

| x-loud | inherit

■ Initial value — medium

■ Applies to — All

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — Refer to inherited value

■ Media groups — Aural

white-space

■ Values — normal | pre | nowrap | inherit

■ Initial value — normal

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual

widows

■ Values — ‹integer› | inherit

■ Initial value — 2

■ Applies to — Block-level elements

■ Inherited — Yes

■ Percentages — N/A

■ Media groups — Visual, paged

461](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-497-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

document.write("Every mile is two in winter.");

}

}

}

You will note that it is easy to make a mistake in coding, especially with the curly braces ({ }),

so you may wish to simplify the coding by using a feature known as a switch (or case) structure.

A switch structure allows you to check for multiple values of a single variable. In the earlier

example, this variable was season.

Here is the same if. . .else structure rewritten as a case structure:

switch (season) {

case "spring":

document.write("The Earth is like a child that knows poems.");

break;

case "summer":

document.write("To see the summer sky is poetry.");

break;

case "autumn":

document.write("Autumn is a second spring, where every leaf is a

flower.");

break;

case "winter":

document.write("Every mile is two in winter.");

break;

}

You would really not necessarily deem this to be shorter than a selection structure, but you have

neatly reduced the number of curly braces from 12 to 2. In other words, you have eliminated 10

possible sources of error.

You may have noticed the use of the break statement. This drops the execution of the pro-

gram out of the case structure once the proper match has been made. If the break statement

were absent, the case structure would still work, but the output would be different. In the first

instance, let us say the value of season is summer. The output then would be: "To see the

summer sky is poetry."

If the break statements were omitted, however, and the variable were still to be summer, the

output would be:

To see the summer sky is poetry.

Autumn is a second spring where every leaf is a flower.

Every mile is two in winter.

Finally, you may, even more simply, put the multivalued variable, season, in an array.

var Season = new Array();

season[0] = "spring";

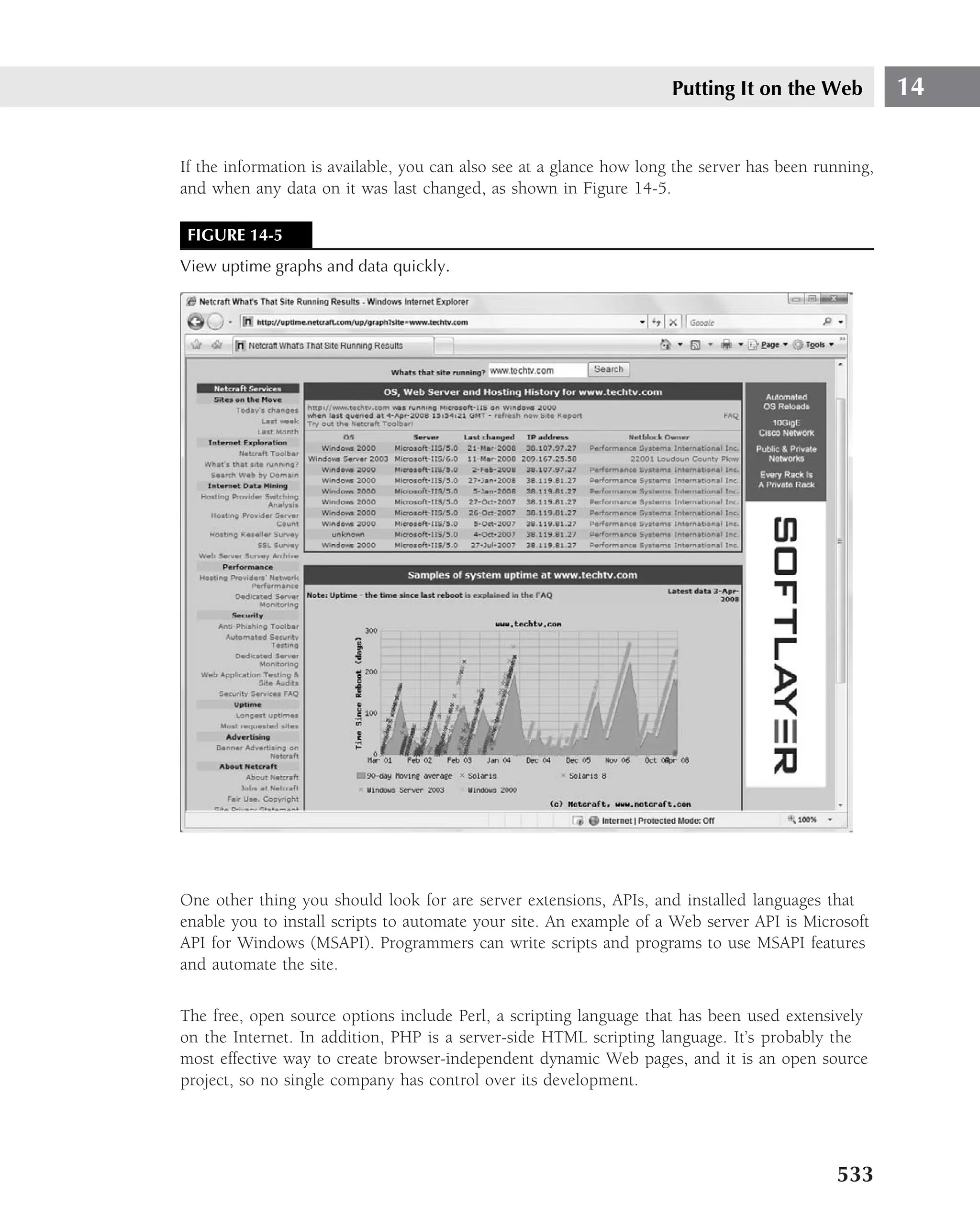

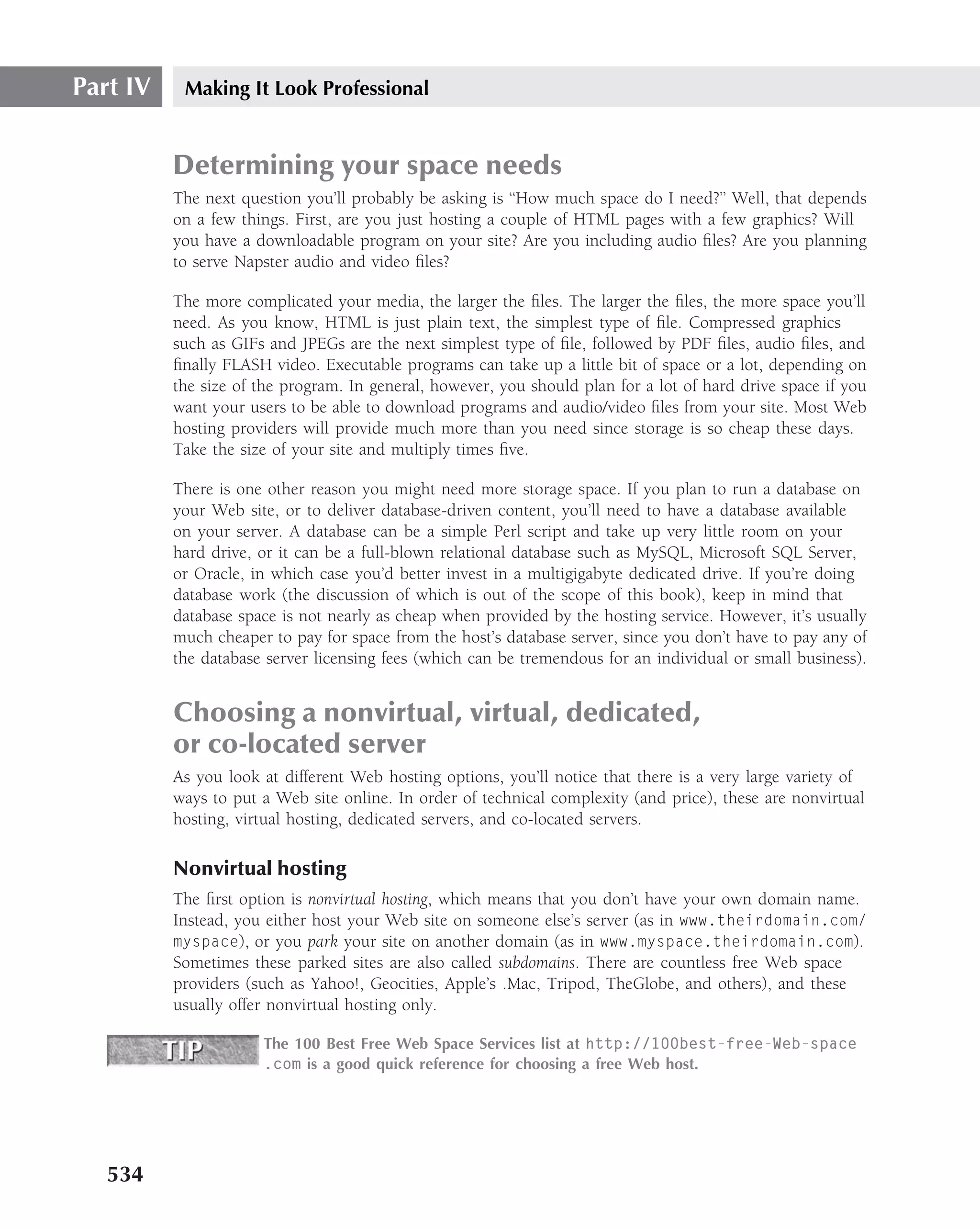

498](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-534-2048.jpg)

![Making Dynamic Pages with JavaScript 13

season[1] = "summer";

season[2] = "autumn";

season[3] = "winter";

However, the number of values is rather small for an array.

If you need to test for multiple conditions before deciding what action to take, if statements

can be nested so that one condition is tested after another one is passed. This says, ‘‘If the first

condition is true, then — and only then — check to see if the second condition is true. If the

second one is true, too, then take an action.’’ The following is the JavaScript version:

if (thisIsTrue) {

if (thatIsTrue) {

doThis;

}

}

The following example tests first to see if a credit card number is correct, and then checks to

see if the balance of available credit is enough to pay for the product. The credit limit is not

checked unless the card number is a valid one. Only if both of these comparisons are true will

the purchase be completed.

if (cardNumber == valid) {

if (limit == highEnough) {

completePurchase();

}

}

You can also nest an if statement within an if...else statement, an if... else statement

within an if statement, or an if...else statement within another if...else statement. The

levels of complexity you can reach are truly mind-blowing, allowing for a practically infinite

number of conditional decisions.

As with any other kind of power, it’s best to exercise this in moderation. If you have

37 different if...else statements nested within 24 different if statements that are

themselves nested within another dozen if...else statements, you’ll never be able to untangle

things if you need to modify the code later. When code appears to be too complex, rethink your

approach.

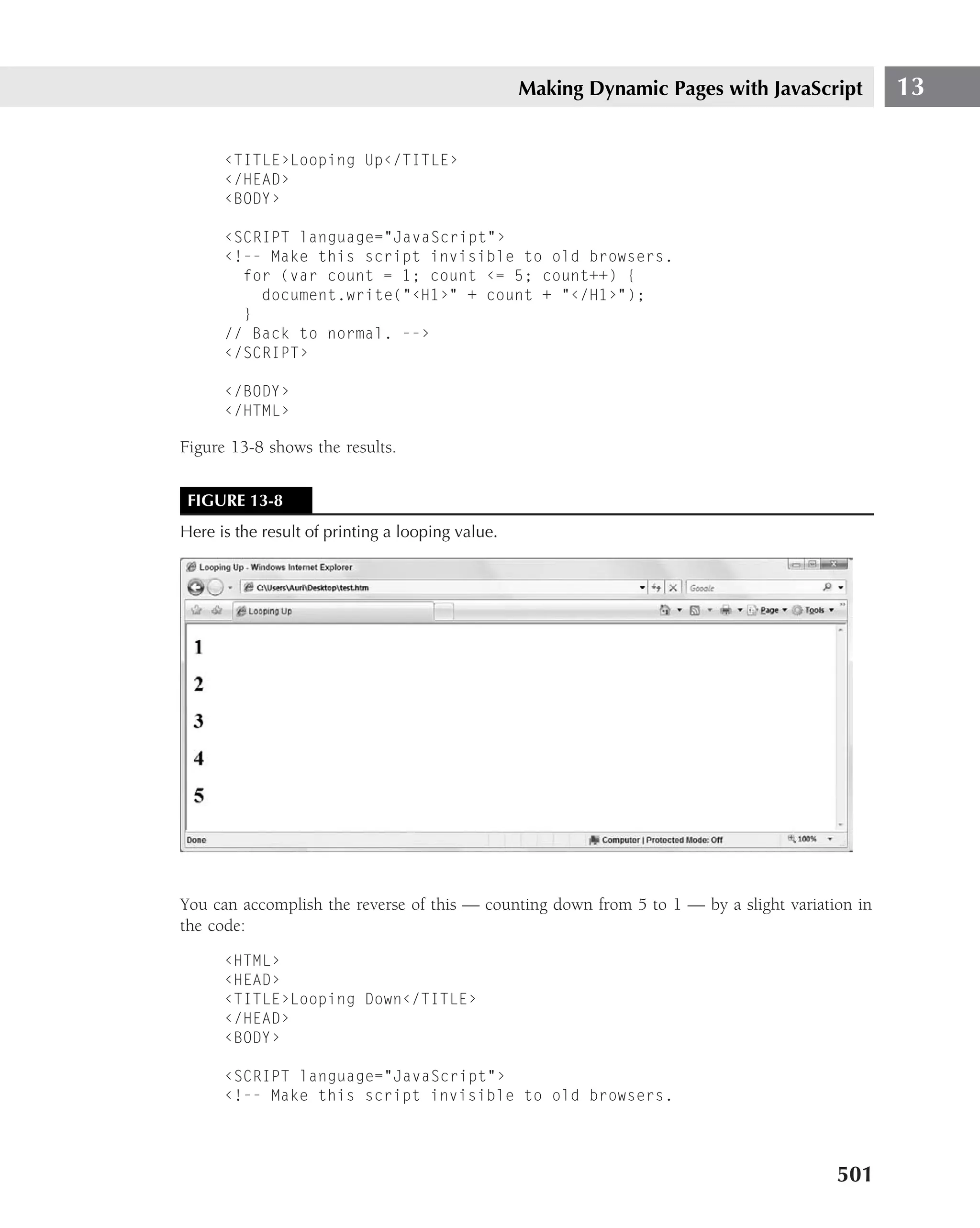

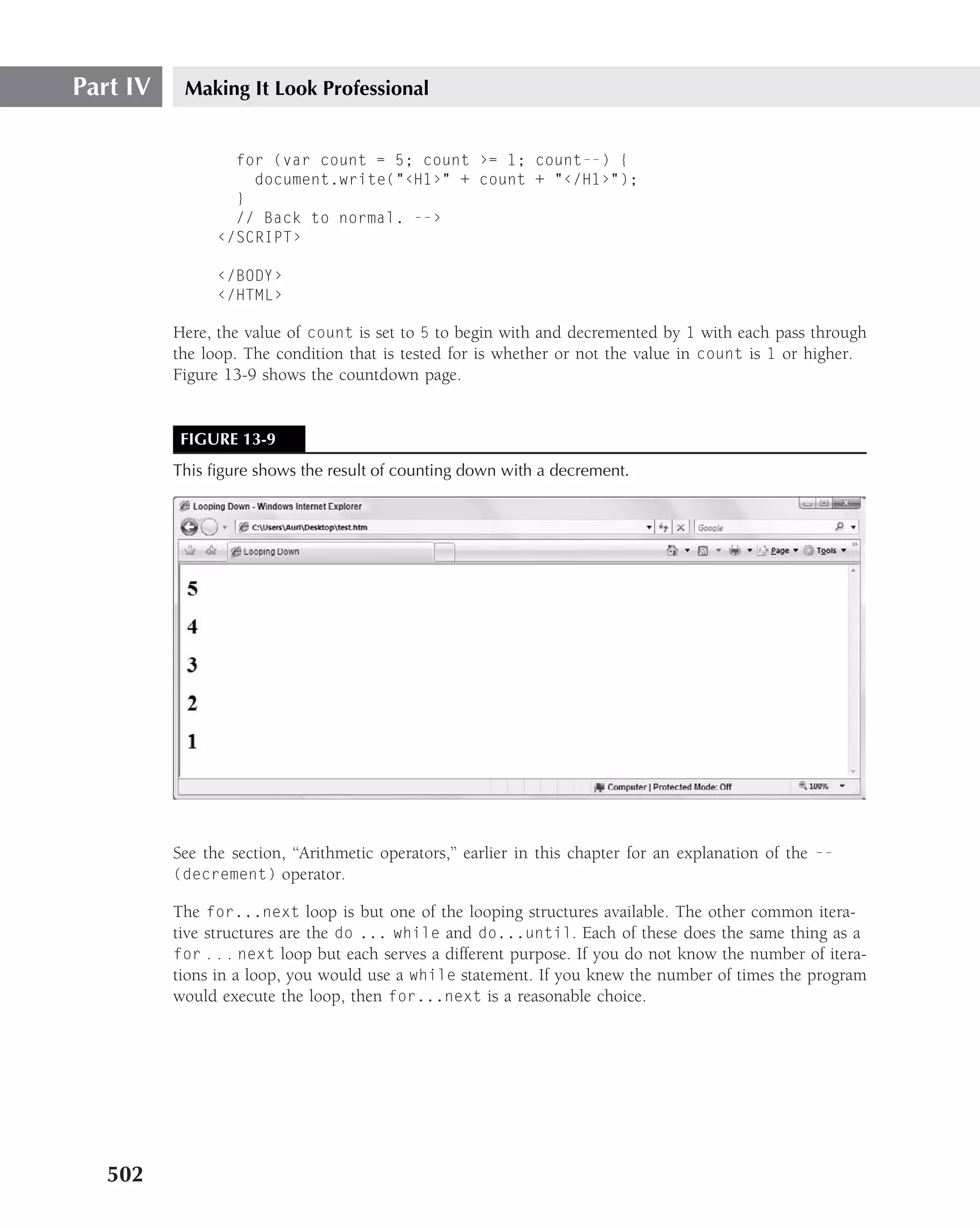

Going in loops

Most of us spend at least some time running around in circles. In JavaScript, you sometimes

want to do this deliberately — a loop, in programming terms. If you’ve ever cooked a turkey

on Thanksgiving, you already know all about loops. You open the oven and look at the meat

thermometer to see if it’s up to the ‘‘poultry’’ mark yet. If it isn’t, you wait a little while, and then

499](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-535-2048.jpg)

![Making Dynamic Pages with JavaScript 13

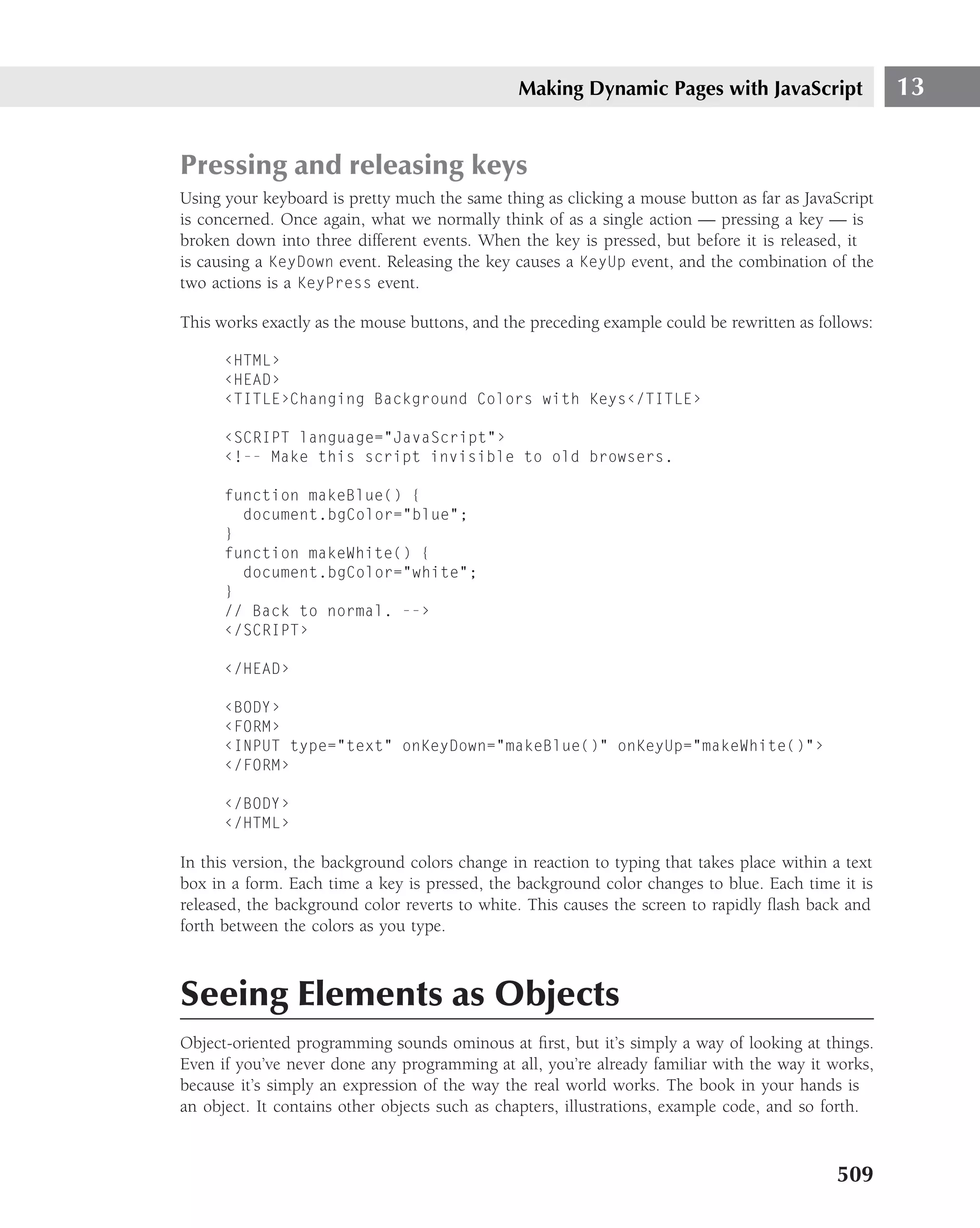

From that point on, all you have to do is to work with the variable. The following example shows

how this can be done in a form that allows a visitor to change the background color of the page:

‹HTML›

‹HEAD›

‹TITLE›Working with Properties‹/TITLE›

‹SCRIPT language="JavaScript"›

‹!-- Make this script invisible to old browsers.

function getColor(){

colorChoice = document.pickAColor.visitorColor.options[document

.pickAColor.visitorColor.selectedIndex].value;

document.bgColor = colorChoice;

}

// Back to normal. --›

‹/SCRIPT›

‹/HEAD›

‹BODY bgcolor="Green"›

‹H1›Pick a color, any color.‹/H1›

‹FORM id="pickAColor" name="pickAColor"›

‹SELECT id="visitorColor" name="visitorColor" onChange="getColor()"›

‹OPTION value="Aqua"›Aqua‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Black"›Black‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Blue"›Blue‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Fuschia"›Fuschia‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Gray"›Gray‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Green"›Green‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Lime"›Lime‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Maroon"›Maroon‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Navy"›Navy‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Olive"›Olive‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Purple"›Purple‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Red"›Red‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Silver"›Silver‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Teal"›Teal‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="White"›White‹/OPTION›

‹OPTION value="Yellow"›Yellow‹/OPTION›

‹/SELECT›

‹/FORM›

‹/BODY›

‹/HTML›

511](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-547-2048.jpg)

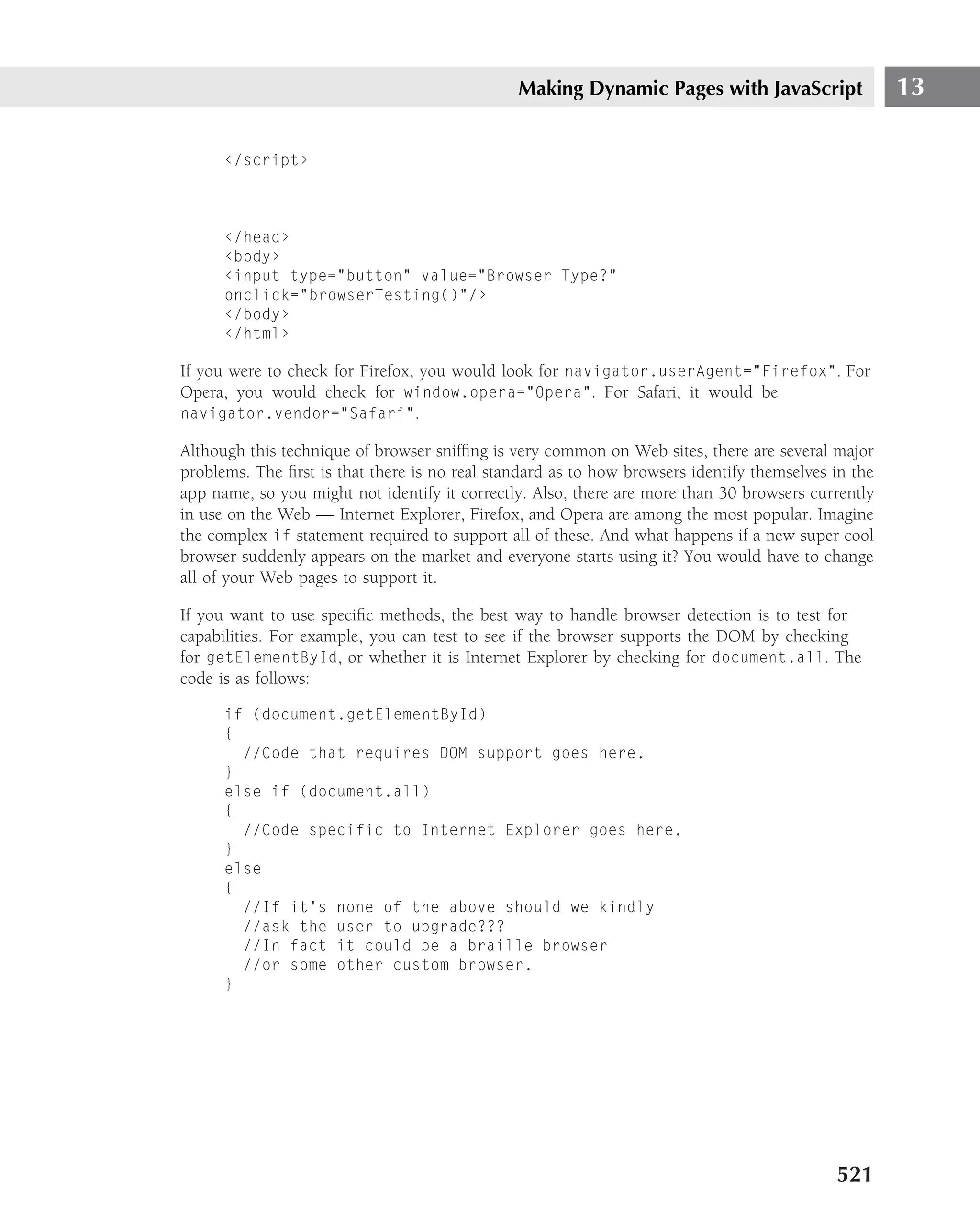

![Making Dynamic Pages with JavaScript 13

method are the text or HTML code to be placed onto the Web page. To add the sentence, ‘‘Hey,

I’m changing the page!’’ to the page, you would write the following:

document.write(Hey, I’m changing the page!);

Remember, you’re not limited to adding only plain text — you can use HTML code as well. The

following variation is just as valid as the original example:

document.write(Hey, I’m ‹I›changing‹/I› the page!);

Form Validation

One of the most common uses of JavaScript is to validate forms before they are submitted to the

Web server.

The following code shows how to verify that the data in a form contains a name and an e-mail

address. It uses regular expressions to perform the validation.

‹html›

‹head›

‹title›Validating Forms‹/title›

‹script language="JavaScript"›

‹!-- Make this script invisible to old browsers.

function check()

{

if (document.form.name.value.length==0 )

{

alert ("You must enter your name");

return false;

};

var nameRe=new RegExp("^[A-Za-z]+$");

if (!nameRe.test(document.form.name.value))

{

alert ("You must enter your name only alphabetic characters

are allowed no spaces");

return false;

}

var emailRe=new RegExp("^ [A-Za-z0-9]+@[A-Za-z0-9.]+$");

if (!emailRe.test(document.form.email.value))

{

alert ("You must enter a valid email address eg: user@host

.com");

return false;

}

return true;

513](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-549-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

};

// Back to normal. --›

‹/script›

‹/head›

‹body›

‹form id="form" name="form" onSubmit="return check();"›

First Name ‹INPUT type="text" id="name" name="name"›

Email ‹INPUT type="text" id="email" name="email"›

‹input type="submit" value="Send"›

‹/form›

‹/body›

‹/html›

In the form, we specify the onSubmit handler to call the function check before the form is

submitted. If the event handler returns false, then the form is not submitted, so we say return

check(). The check function validates the form and returns true if it is valid.

The following expression returns the number of characters in the string entered in the name text

box. If it is zero then we ask the user to enter something.

document.form.name.value.length

Now for the complicated part — regular expressions. Regular expressions (REs) are used to

search for matches of a particular character sequence in text. They are part of many program-

ming languages — the Unix operating system uses them extensively in tools from the command

line, and they have been included in JavaScript since version 1.1.

The following is brief (and simplified) explanation of REs.

You are probably familiar with wildcard characters such as ? (representing one character) and

* (representing any number of characters) in the DOS and Unix command line. The regular

expression for ? would be a period (.), followed by any character, or alternatively [A-Za-z0-9],

which means one character in the ranges of A to Z, a to z, and 0 to 9. If it is not in the given

ranges, then it doesn’t match. So, for *, it would be:

.*

or alternatively:

[A-Za-z0-9]*

The * at the end means zero or more of the preceding character or range of characters. It’s a bit

confusing that the RE for * has a * in it, but you have to bear in mind that they are different

514](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-550-2048.jpg)

![Making Dynamic Pages with JavaScript 13

syntaxes. If we wanted one or more, we could write:

[A-Za-z0-9][A-Za-z0-9]*

But there is a better way:

[A-Za-z0-9]+

Here, + means one or more of the previous expression. In the preceding code, we checked the

name with:

RegExp("^ [A-Za-z]+$")

This is because when the test method of the RE is called it returns true if the character sequence

is found anywhere in the text. However, we want it to only return true if the whole text given

corresponds to the RE. The ^ character specifies the start of the text and the $ specifies the end

of the text.

So, ^[A-Za-z]+$ translates into English as a match for text that, from start to end, is composed

of a sequence of one or more alphabetic characters. Now for the e-mail:

^ [A-Za-z0-9]+@[A-Za-z0-9.]+$

It starts with a sequence of one or more alphanumeric characters, has a @ in the middle, and

then ends with a sequence of one or more alphanumeric characters. However, this isn’t quite

specific enough for a real e-mail address. If you really want to graduate in REs, take a look at

the following:

^[A-Za-z0-9]+[-A-Za-z0-9._]*@([-A-Za-z0-9]+.)+[A-Za-z]{2,5}$

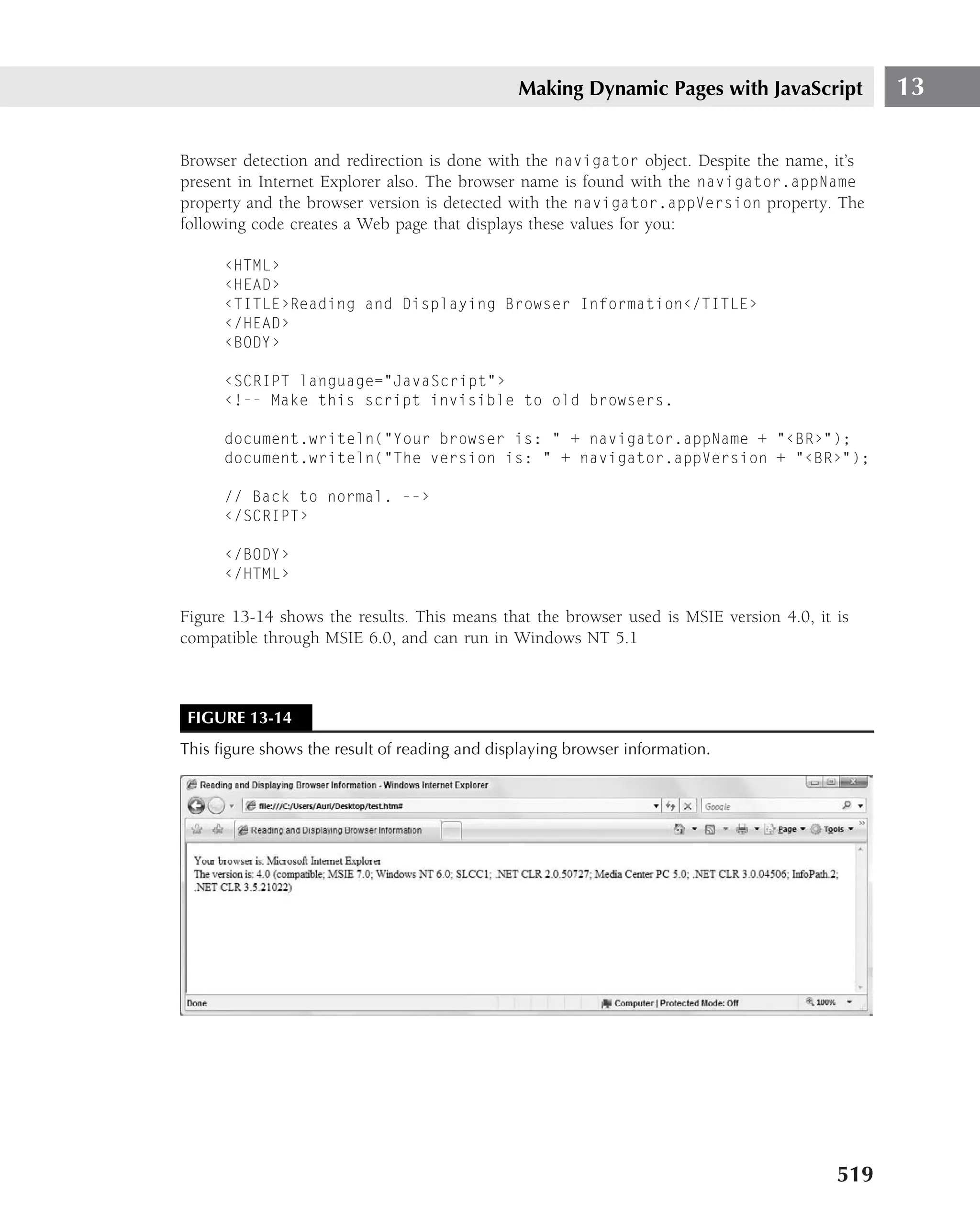

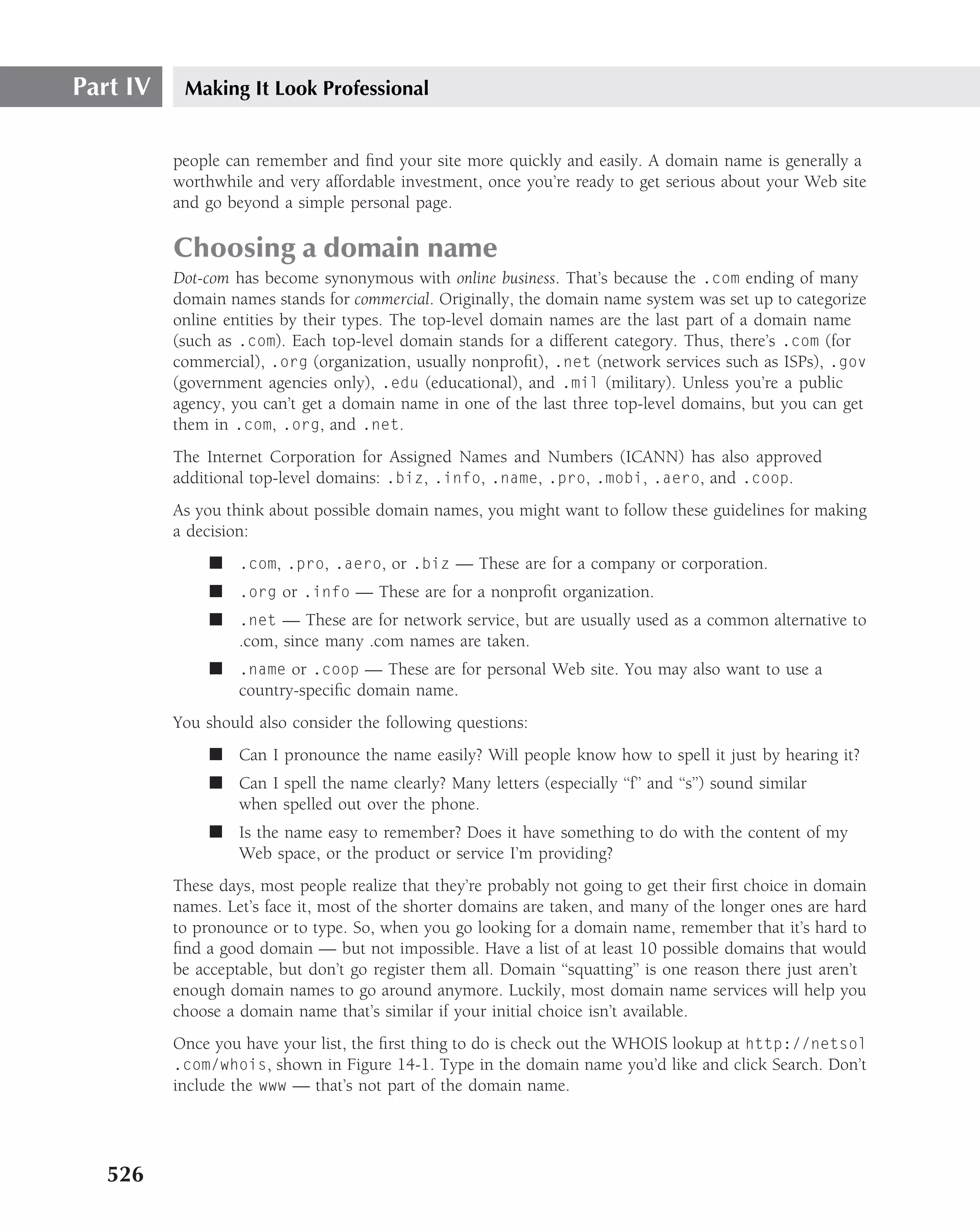

Table 13-5 takes you through this complex example of REs step by step.

TABLE 13-5

Complex Example of Regular Expressions

Part of the Regular Expression Explanation

ˆ Starts with.

[A-Za-z0-9] + A sequence of one or more alphanumeric characters.

[-A-Za-z0-9. ]* A sequence of zero or more alphanumeric characters or -, . or _.

The – is specified as the first character because in this position it

doesn’t signify a range just the character itself.

([-A-Za-z0-9] + .) + The brackets turn a list of expressions into one group expression,

so this really means one or more of the sequences alphanumeric

character or - followed by a ., so this matched abc.xyz.

515](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-551-2048.jpg)

![Part IV Making It Look Professional

You can also check to see if check boxes, option buttons, or menu options are being selected.

The following example shows how:

‹html›

‹head›

‹title›Validating Forms‹/title›

‹script language="JavaScript"›

‹!-- Make this script invisible to old browsers.

function check()

{

if(! (document.form.football.checked && document.form

.swimming.checked))

{

alert("We only accept members who play football and swim so

you might as well select them both");

return false;

}

if (document.form.gender[0].checked)

{

alert("You have to select your gender");

return false;

}

if (document.form.language.selectedIndex==0)

{

alert("Please select a language");

return false; }

return true;

};

// Back to normal. --›

‹/script›

‹/head›

‹body›

‹h2›Club Membership‹/h2›

‹form id="form" name="form" onSubmit="return check();"›

First Name ‹INPUT type="text" id="name" name="name"›

‹br›

Gender

‹input type="radio" name="gender" value="none" checked="checked"›

‹input type="radio" name="gender" value="male"›

‹input type="radio" name="gender" value="female"›

‹br›

Hobbies

‹input type="checkbox" name="football"›

‹input type="checkbox" name="swimming"›

516](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-552-2048.jpg)

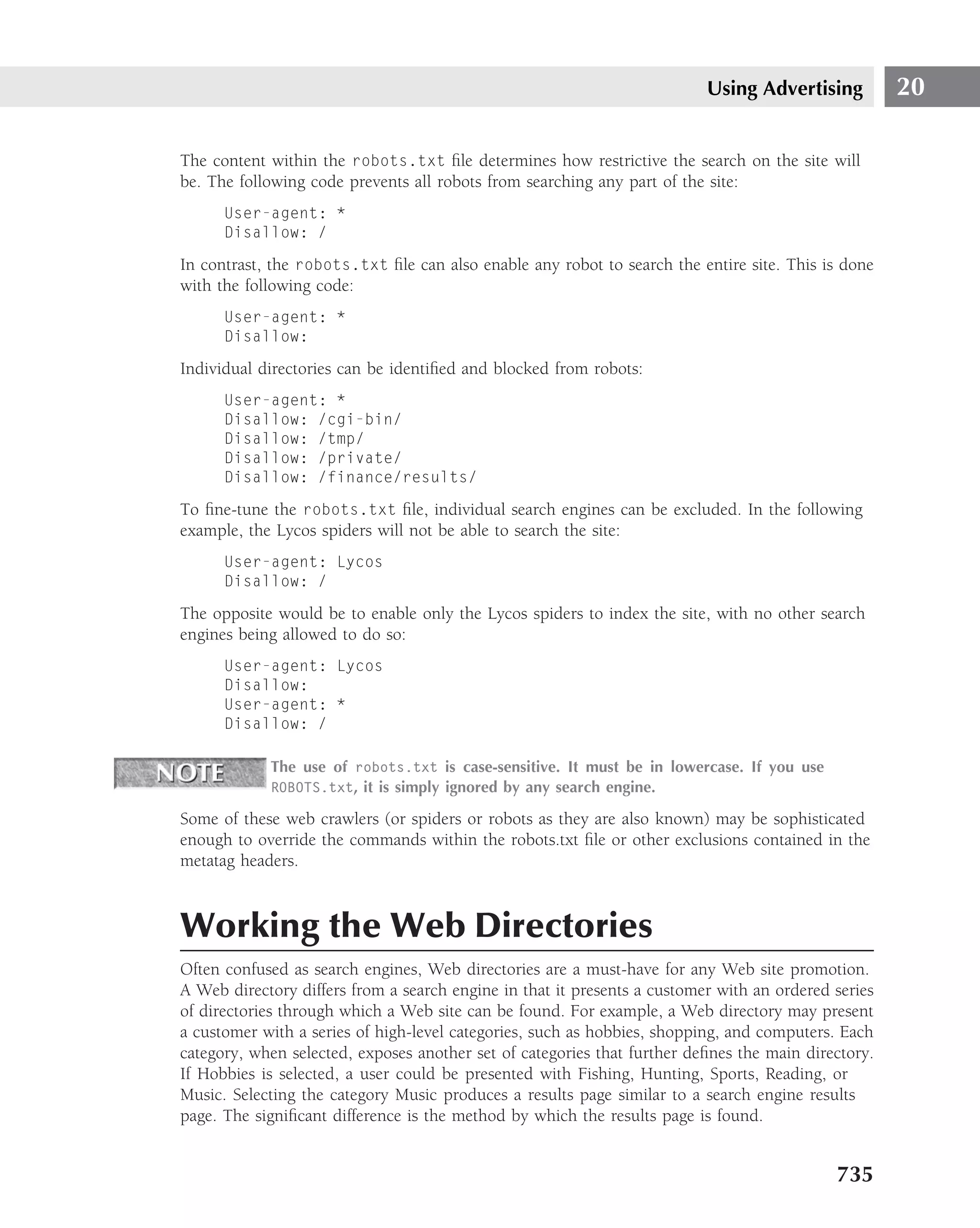

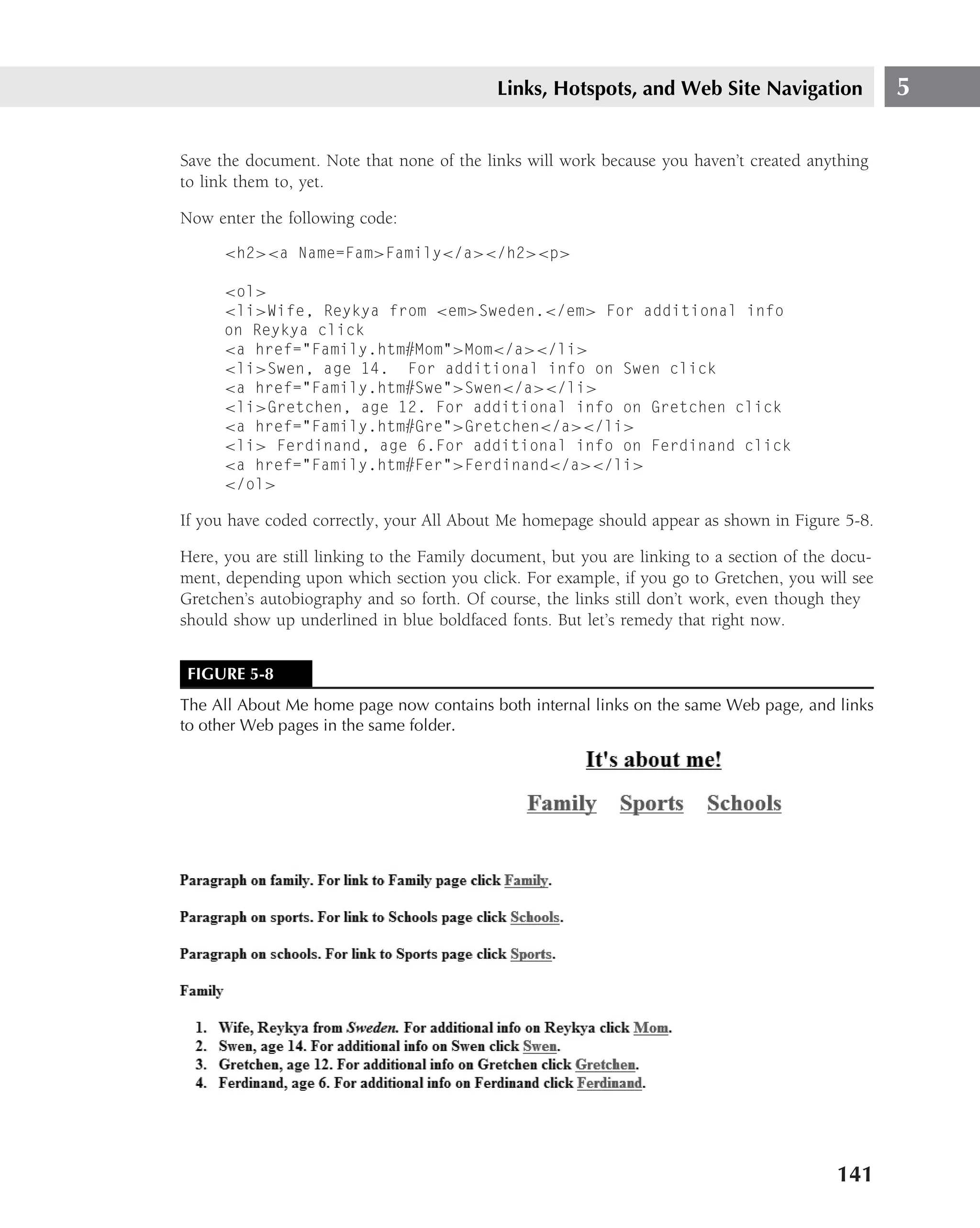

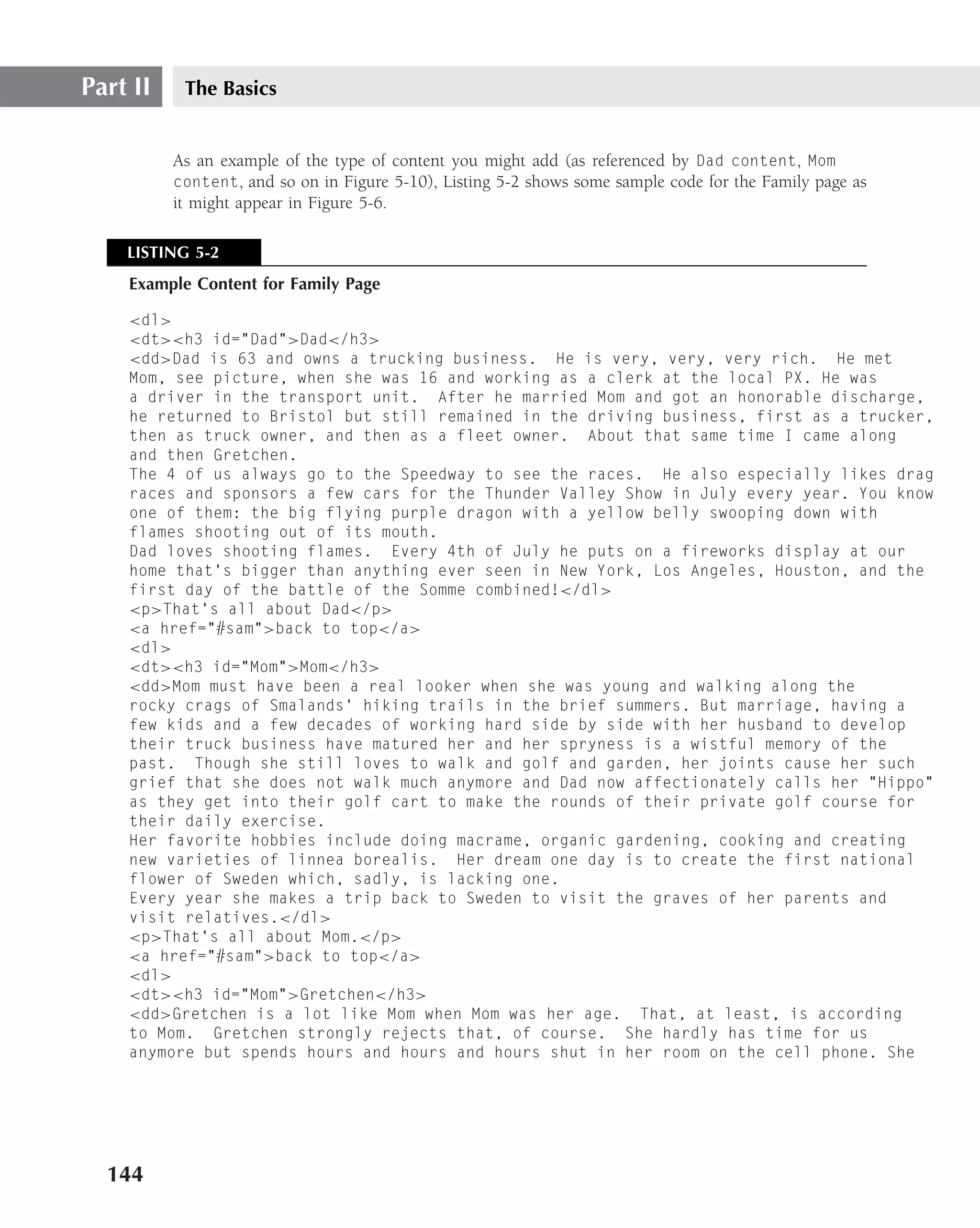

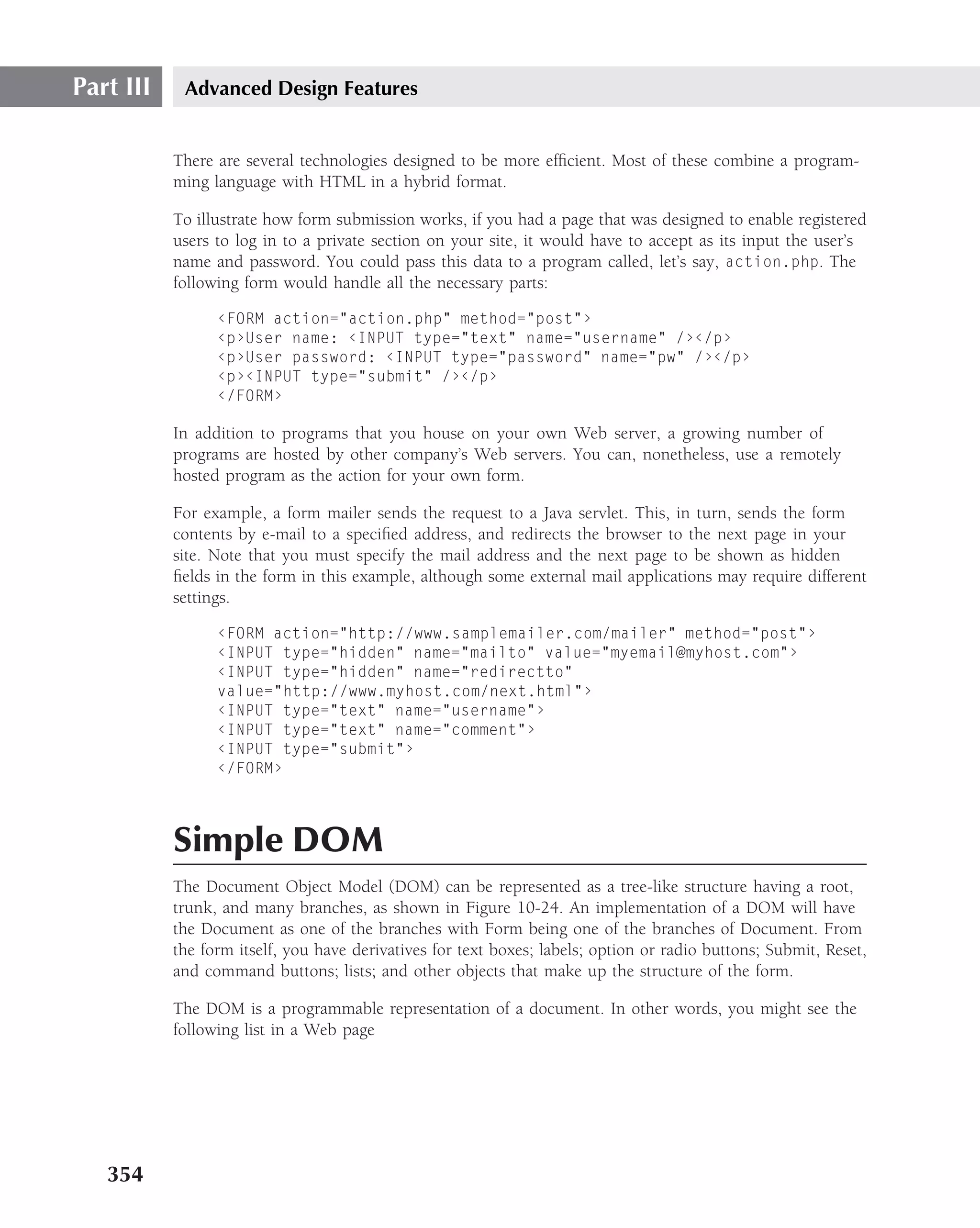

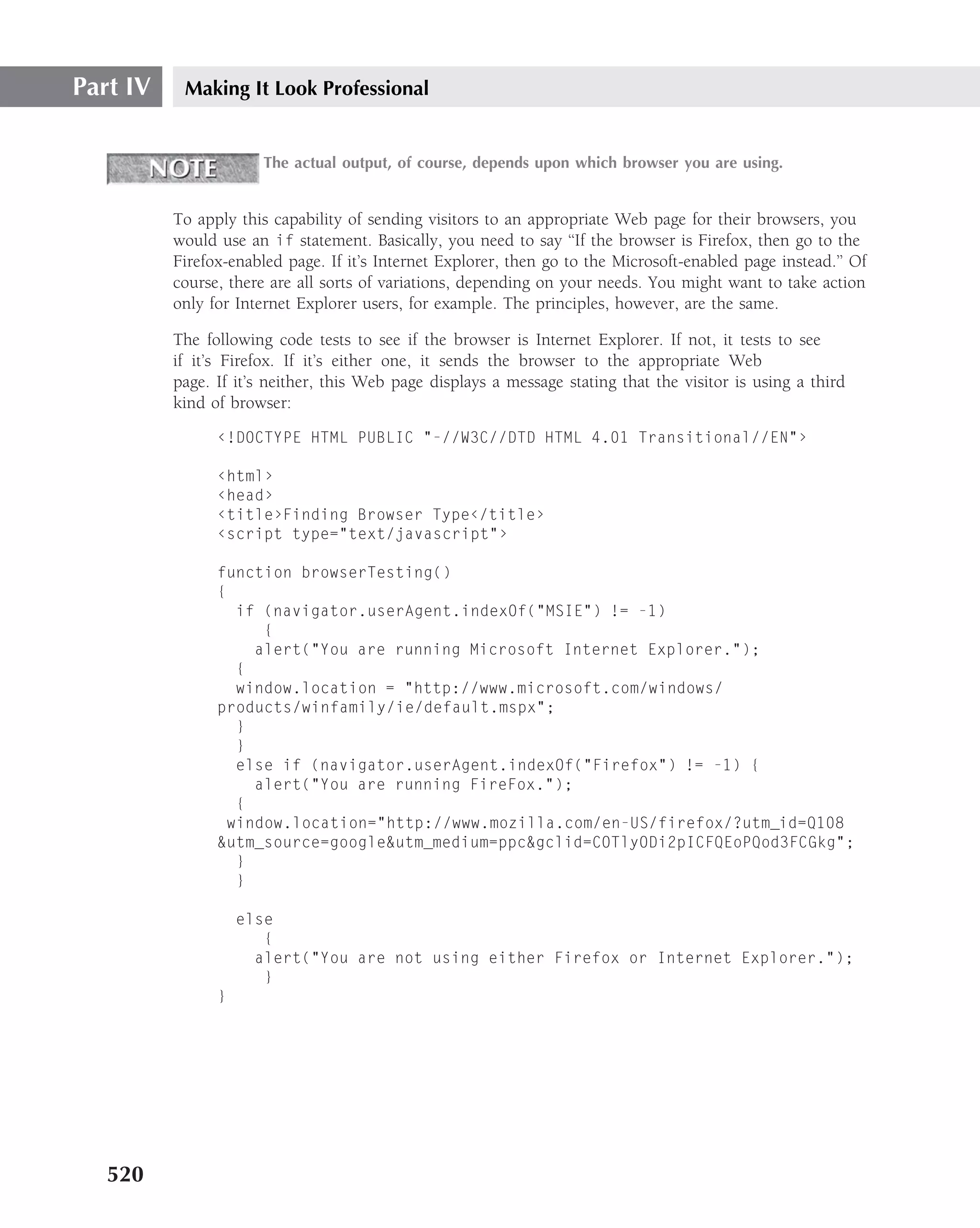

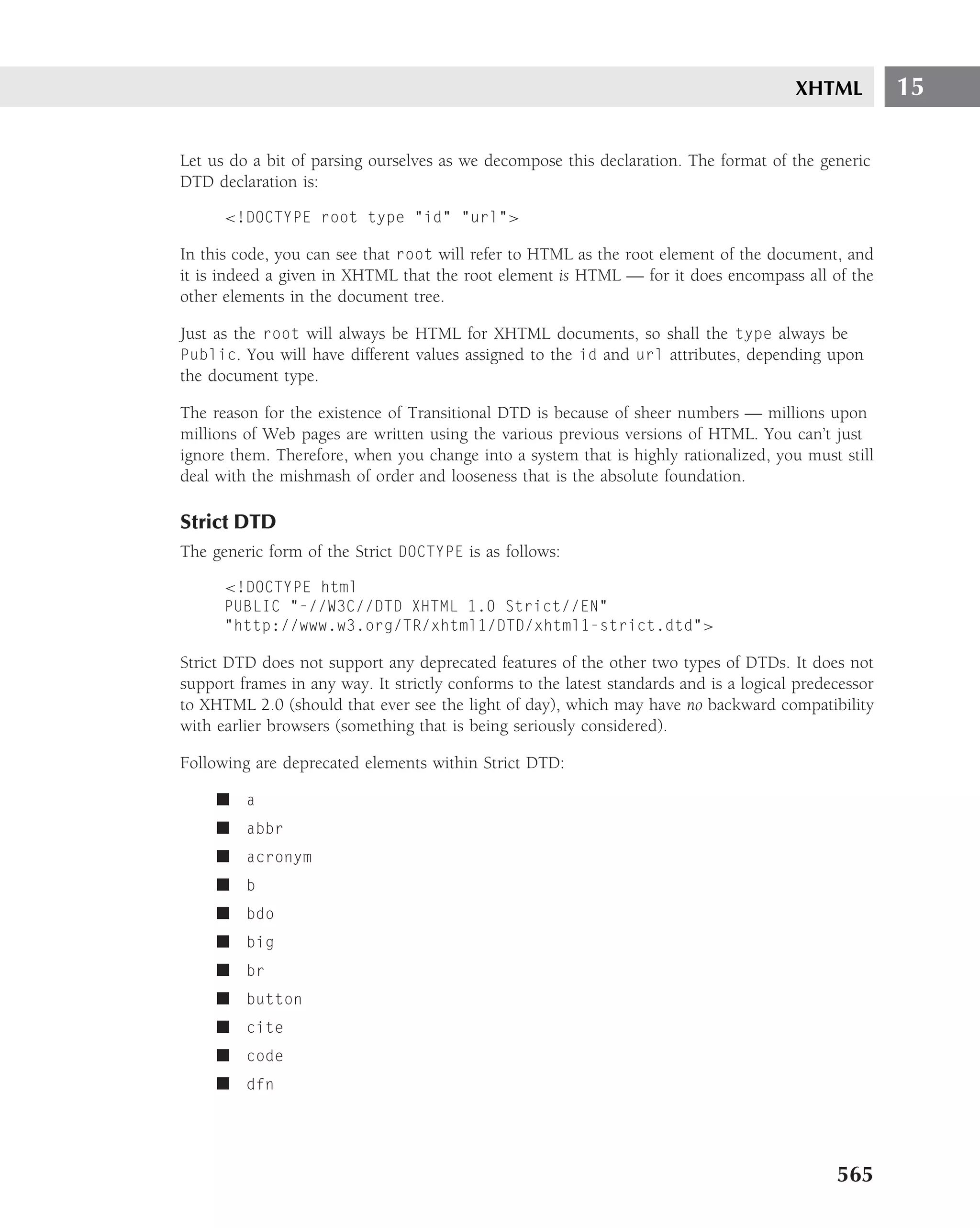

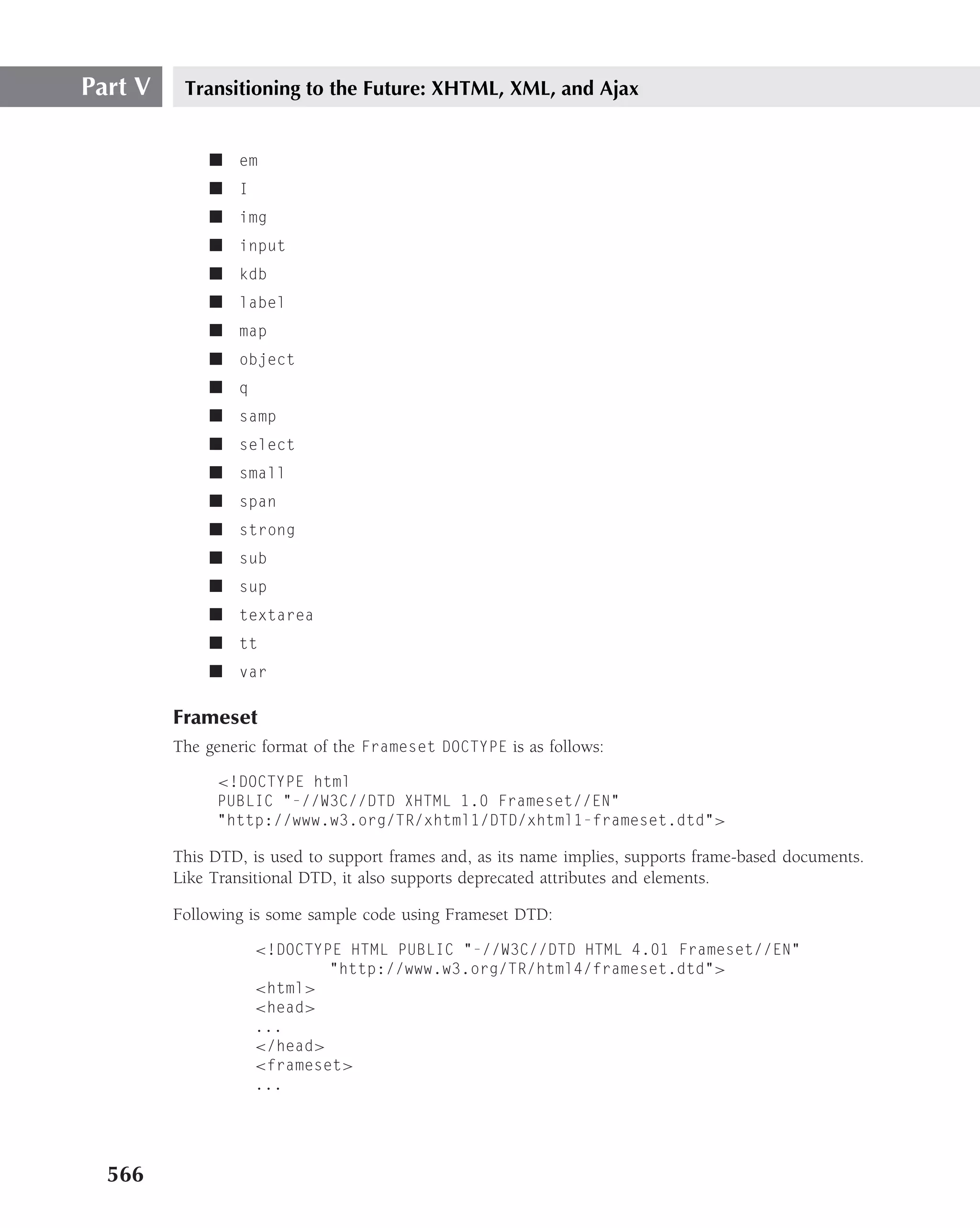

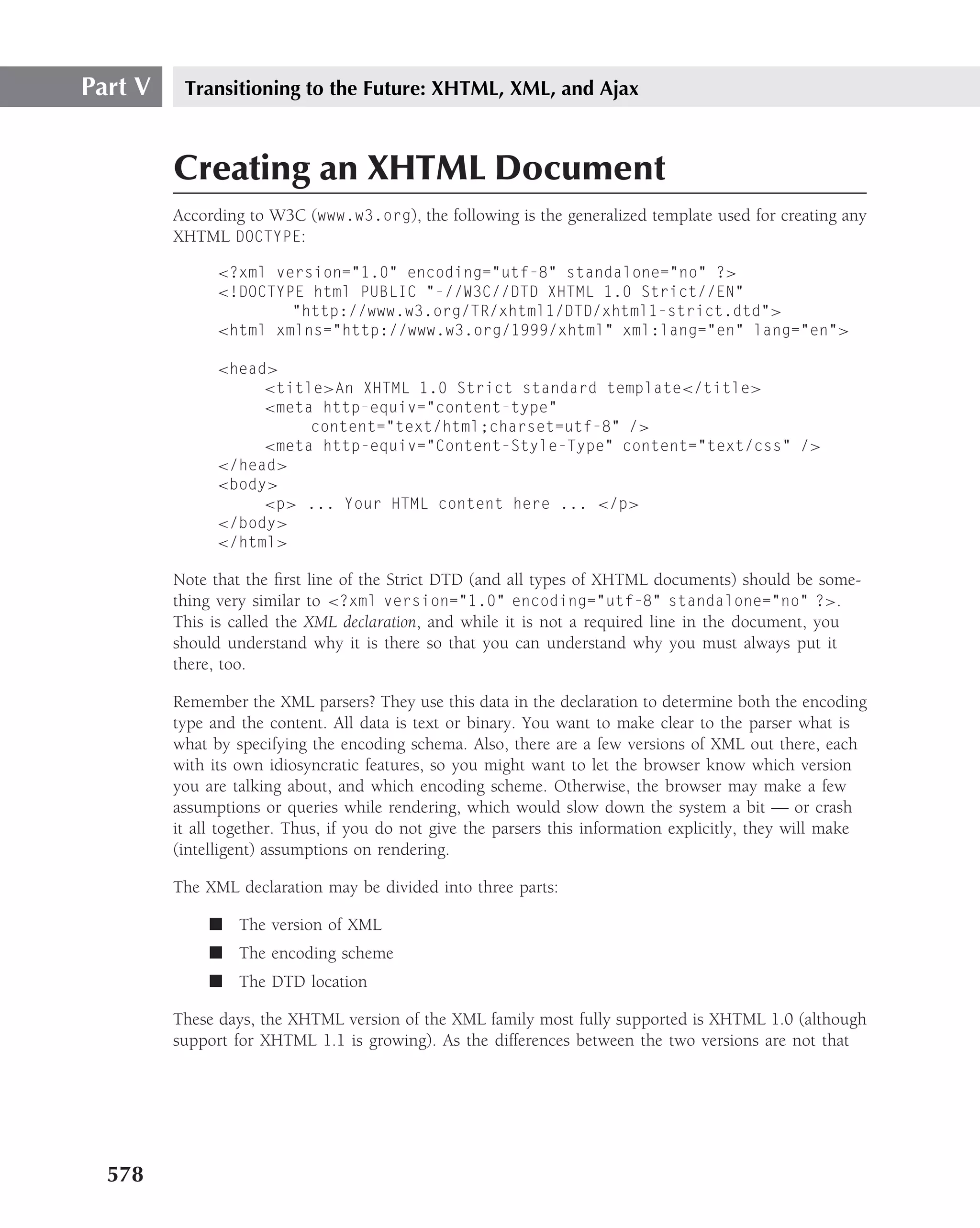

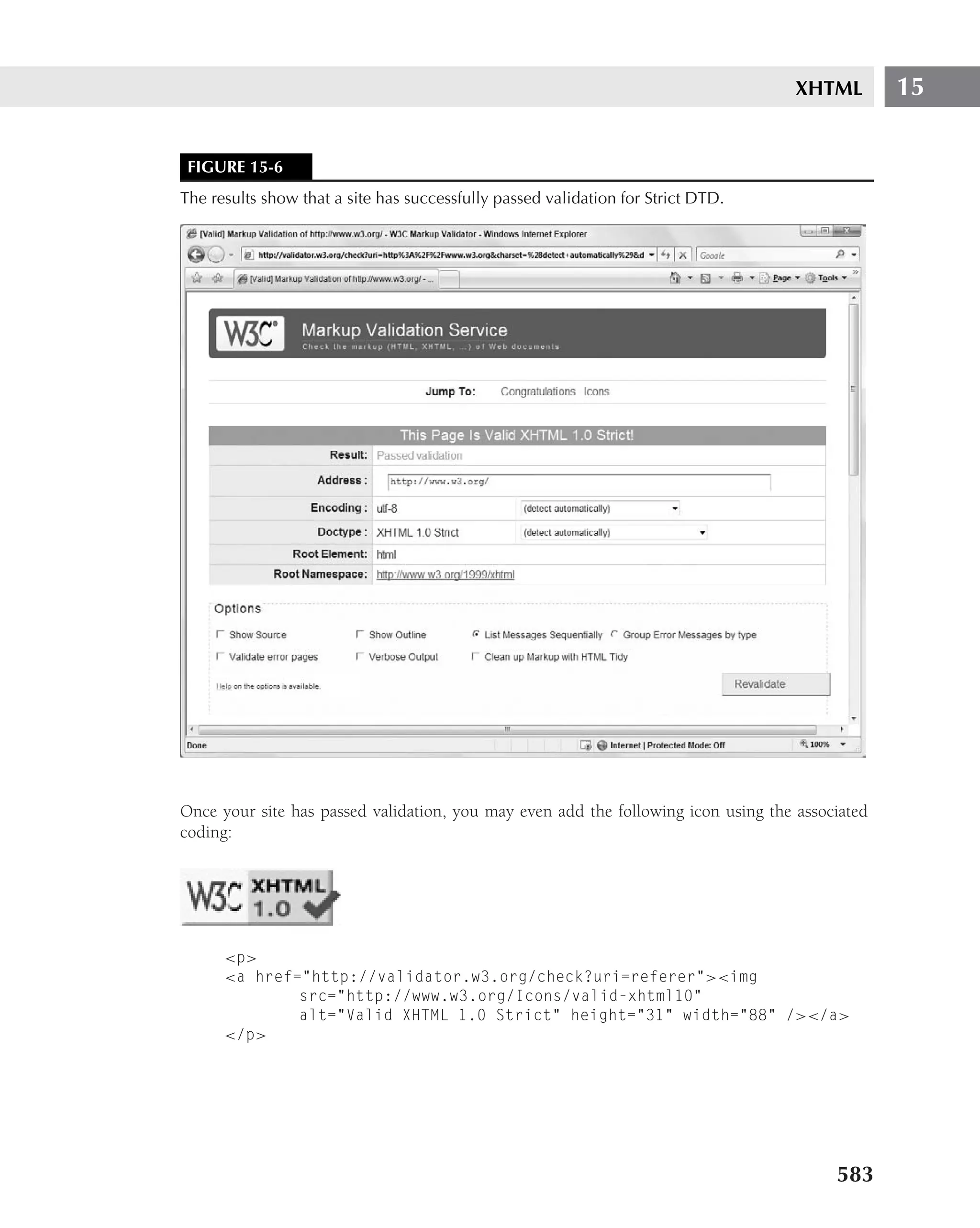

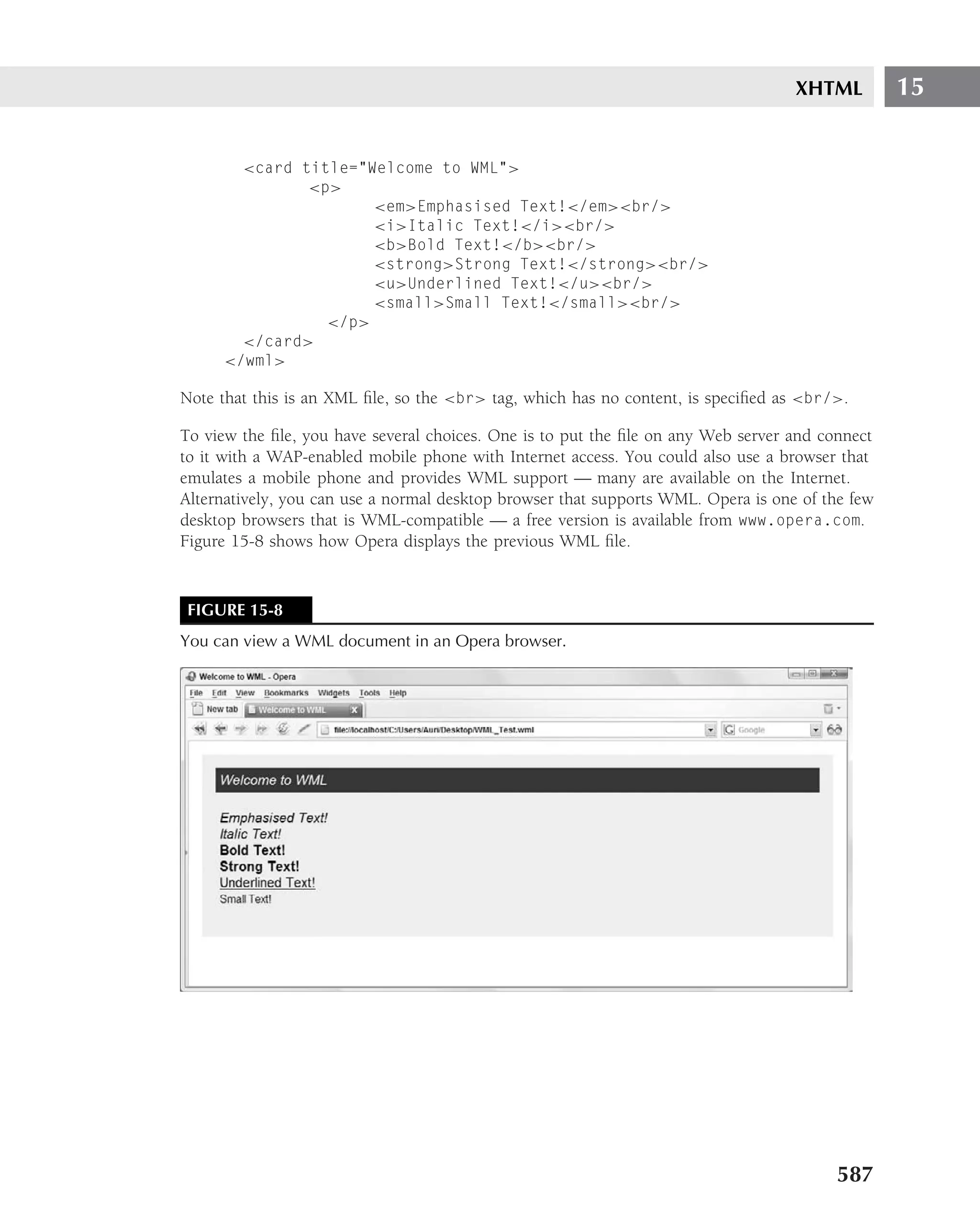

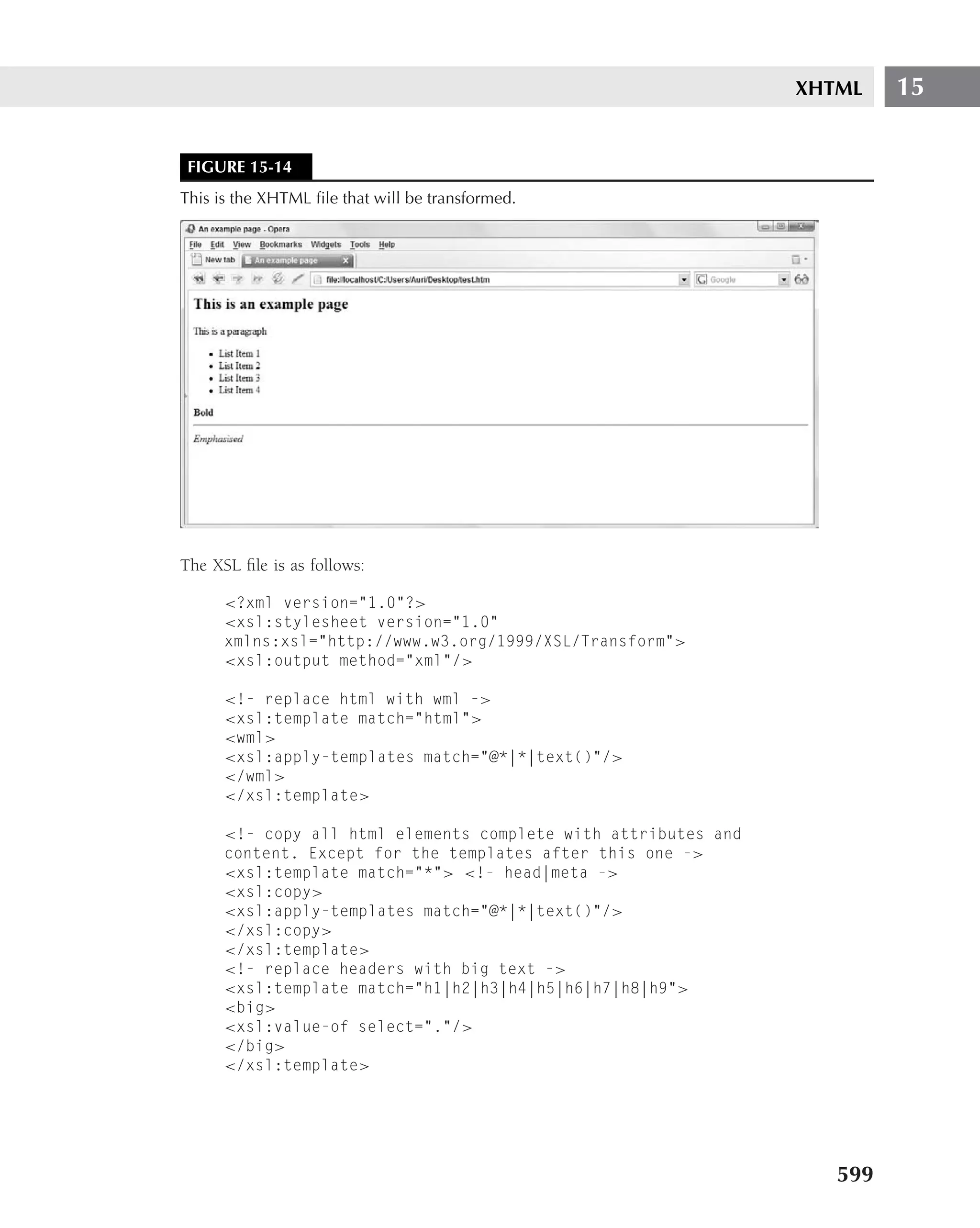

![XHTML 15

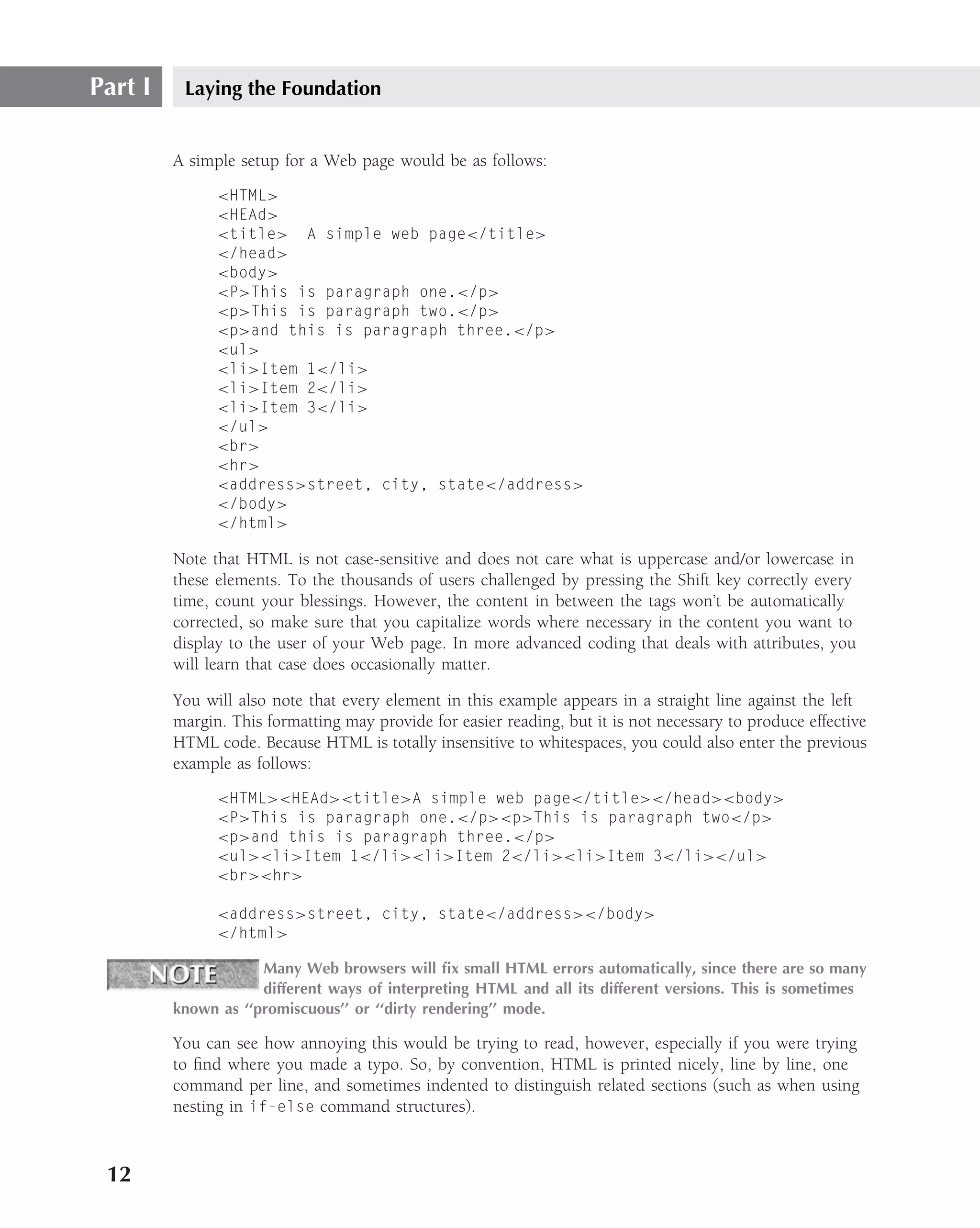

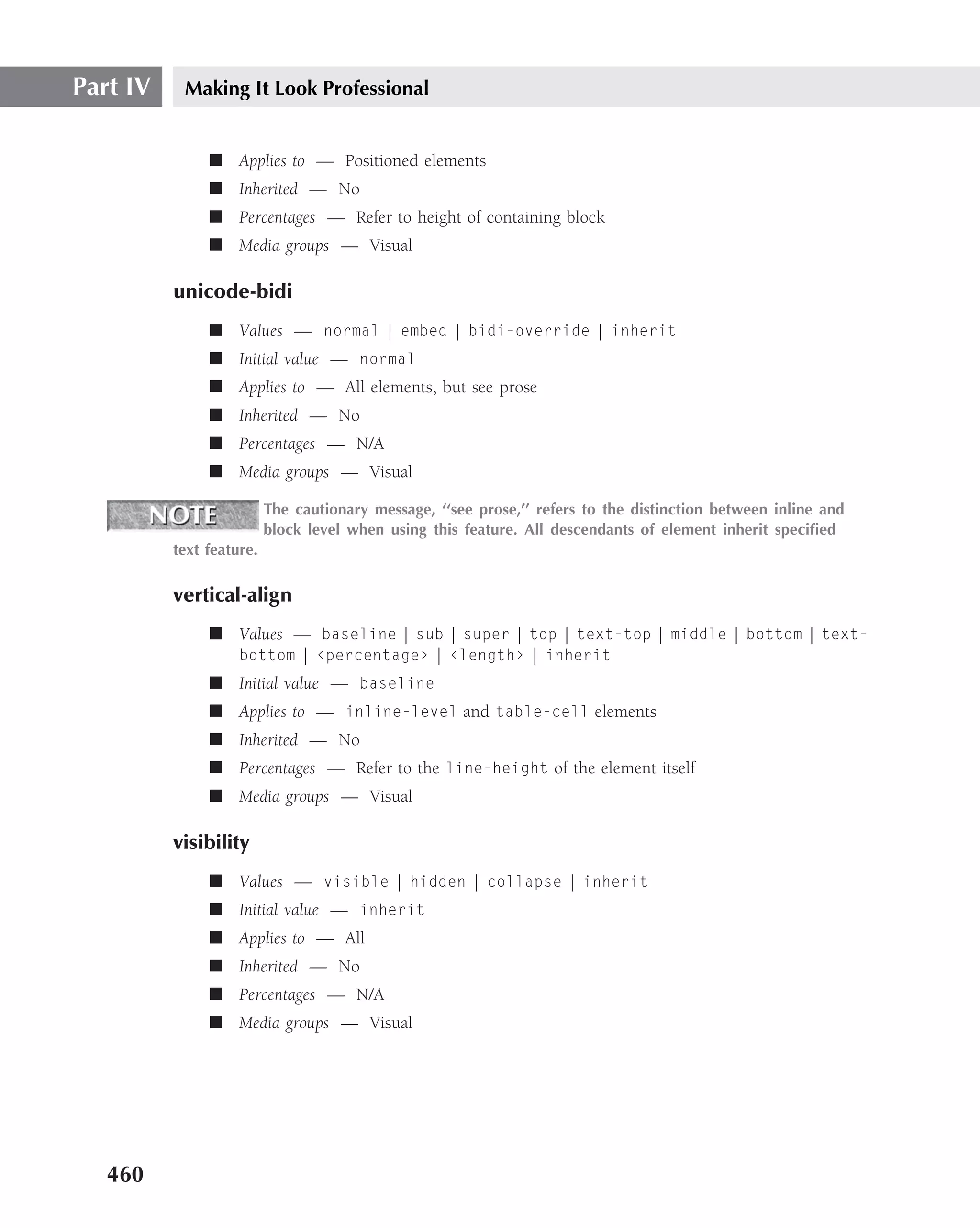

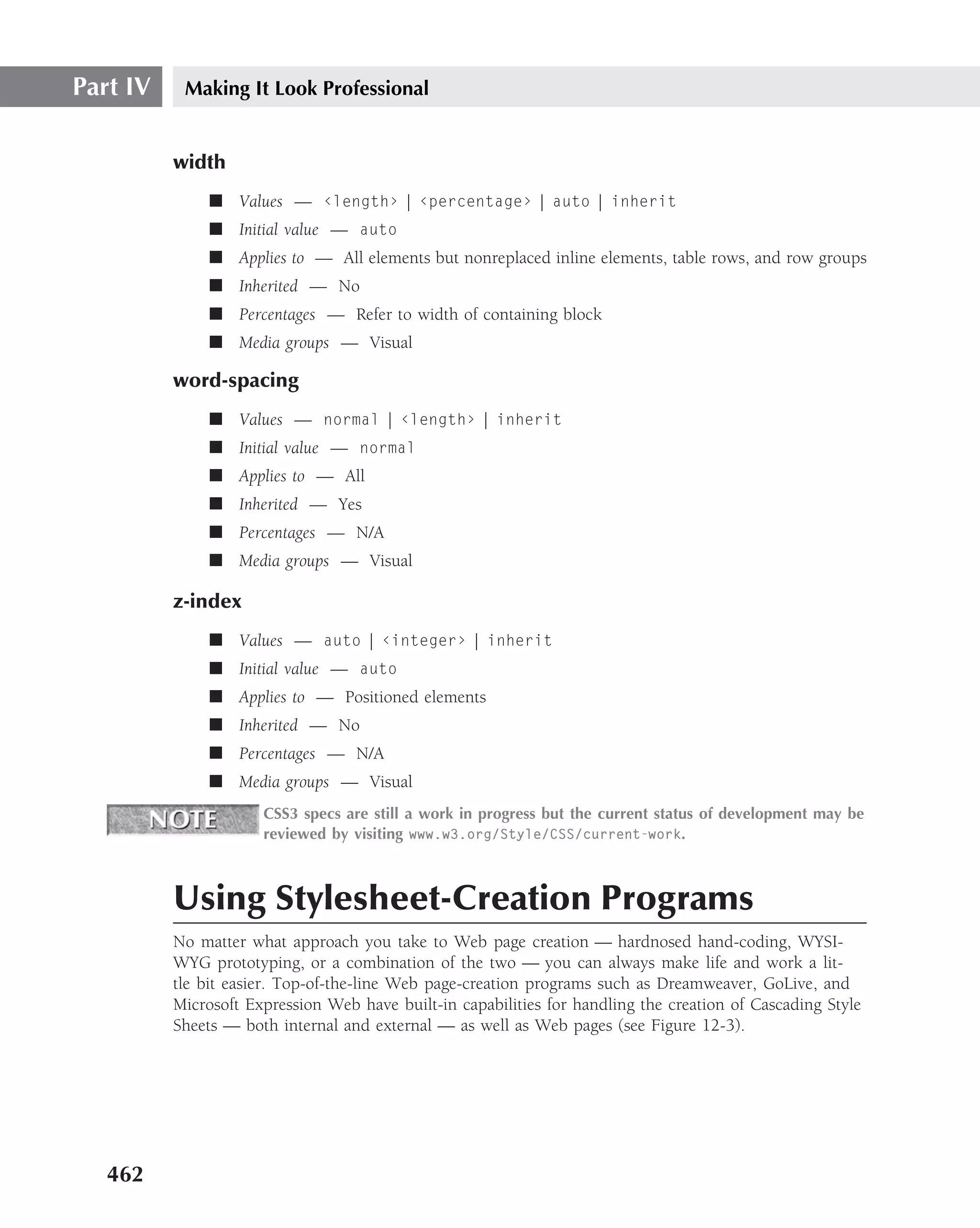

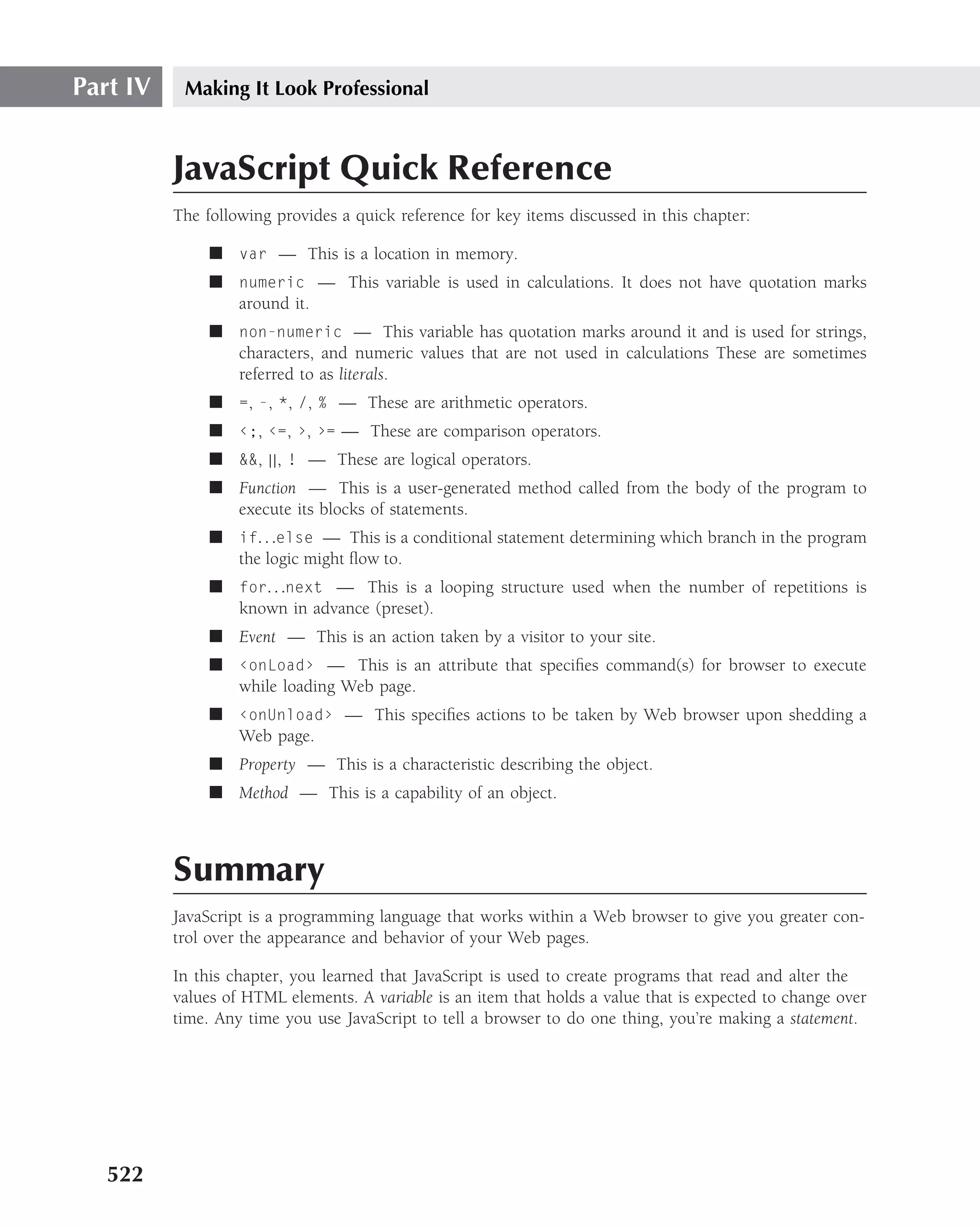

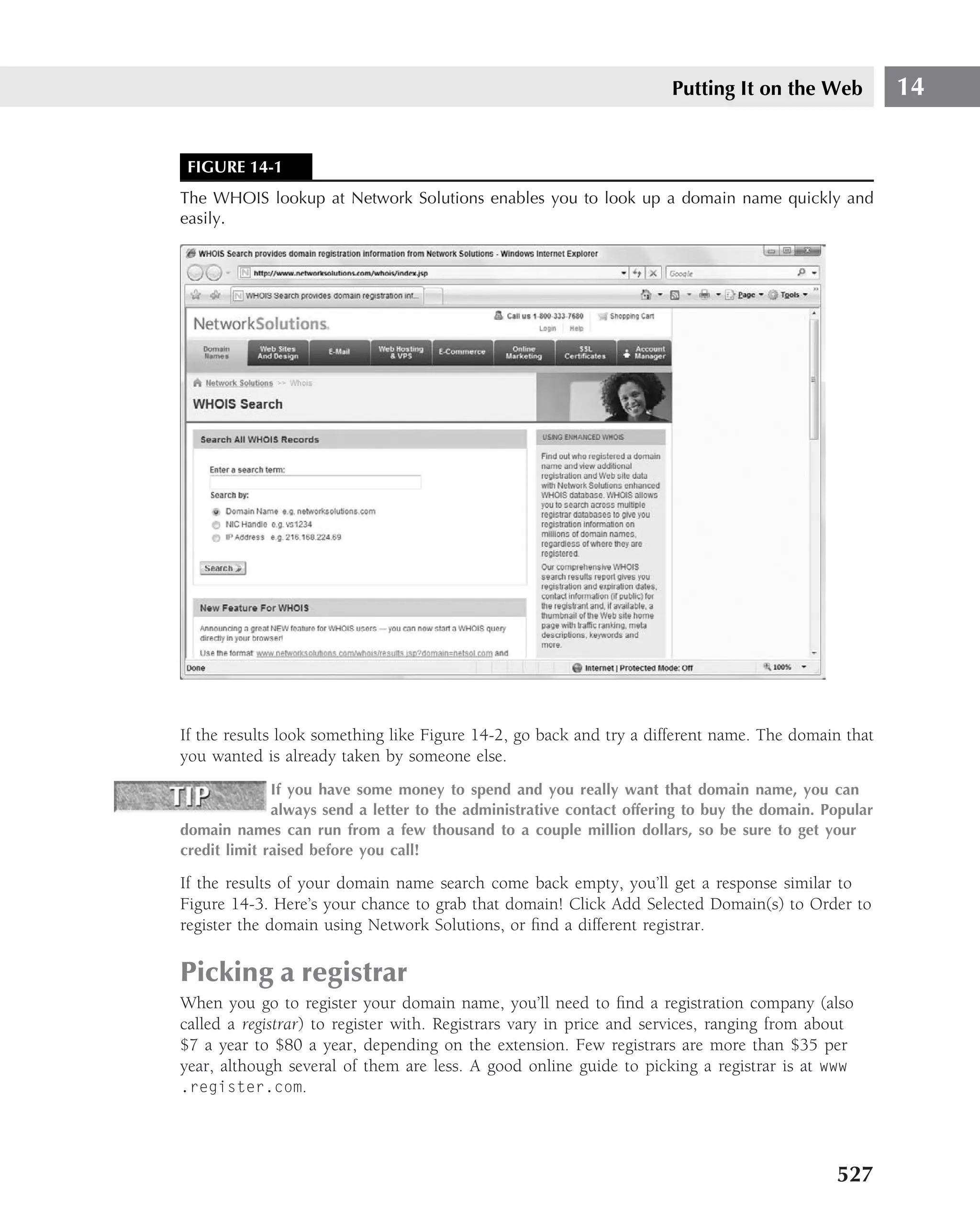

FIGURE 15-4

The extended ASCII code was implemented to provide a character set for numerous other symbols

that exceeded the limits of the original ASCII.

In the event that data had embedded in it multiple instances of characters that could be misread

by the browser as parsed rather than unparsed data (and cause a system crash), the data could

be enclosed within a set of brackets that indicated the parser should ignore the data within the

brackets. Occasionally, when using style commands, you may have data that would cause the

system to render the page incorrectly, and this would be a good candidate to enclose within

the brackets.

The formatting of a CDATA block is:

<![CDATA [

Enter the code you do not wish to be rendered here.

]]>

You will automatically note that the one piece of code you cannot use in a CDATA

block is the brackets because the parser, or Web browser, might read it.

White space

After the CDATA and the PCDATA have been dealt with, pretty much all that remains is the

white space. In HTML, the white space is automatically removed unless preserved by the use of

the <pre>structured content </pre> element.

581](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-617-2048.jpg)

![Part V Transitioning to the Future: XHTML, XML, and Ajax

{

case 1: System.out.println("Go to the Gym");

break;

case 2: System.out.println("Go to the Humanities Bldg.");

break;

case 3: System.out.println("Go to Harrison-Jones");

break;

case 4: System.out.println("Go to Science Hall");

break;

}

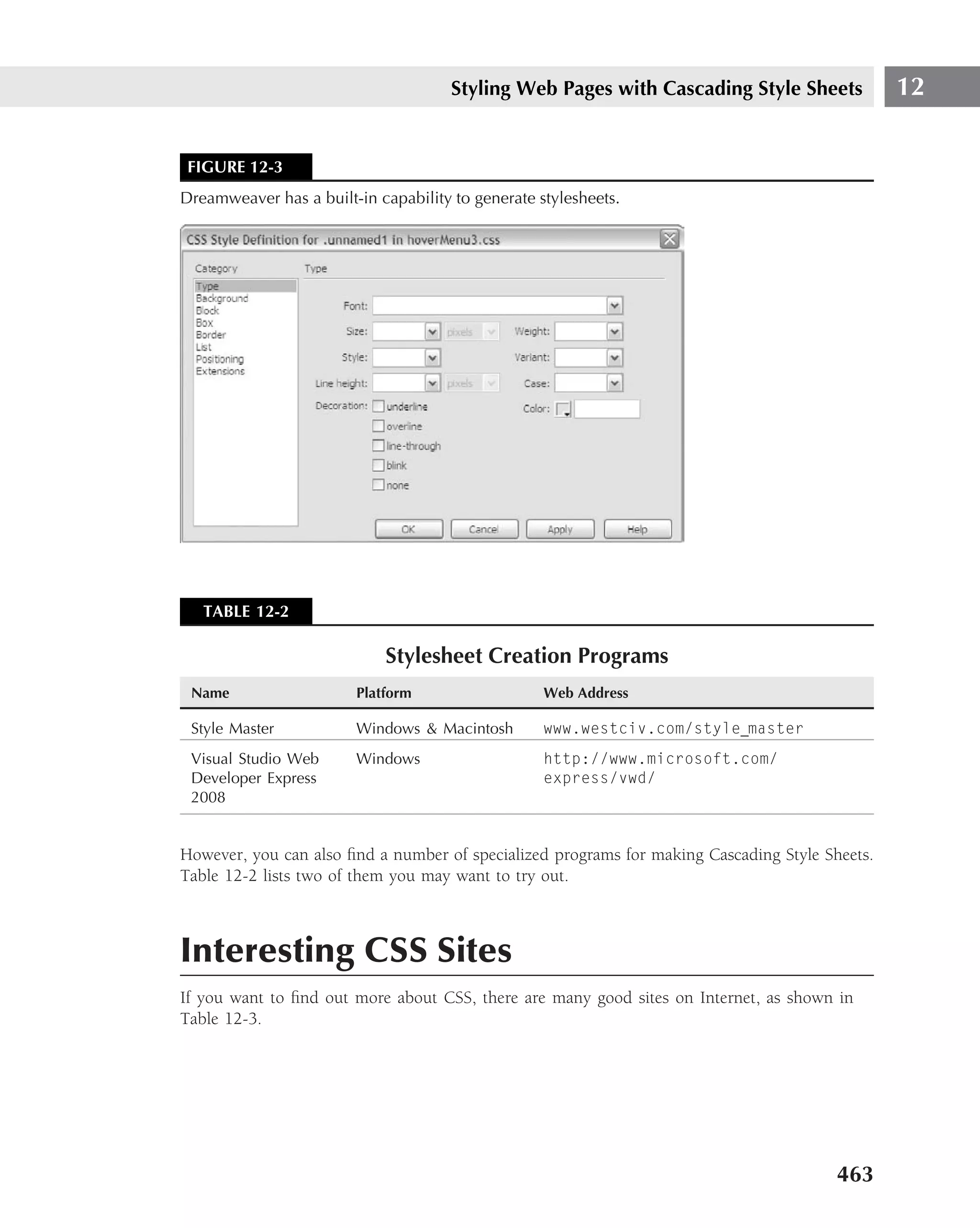

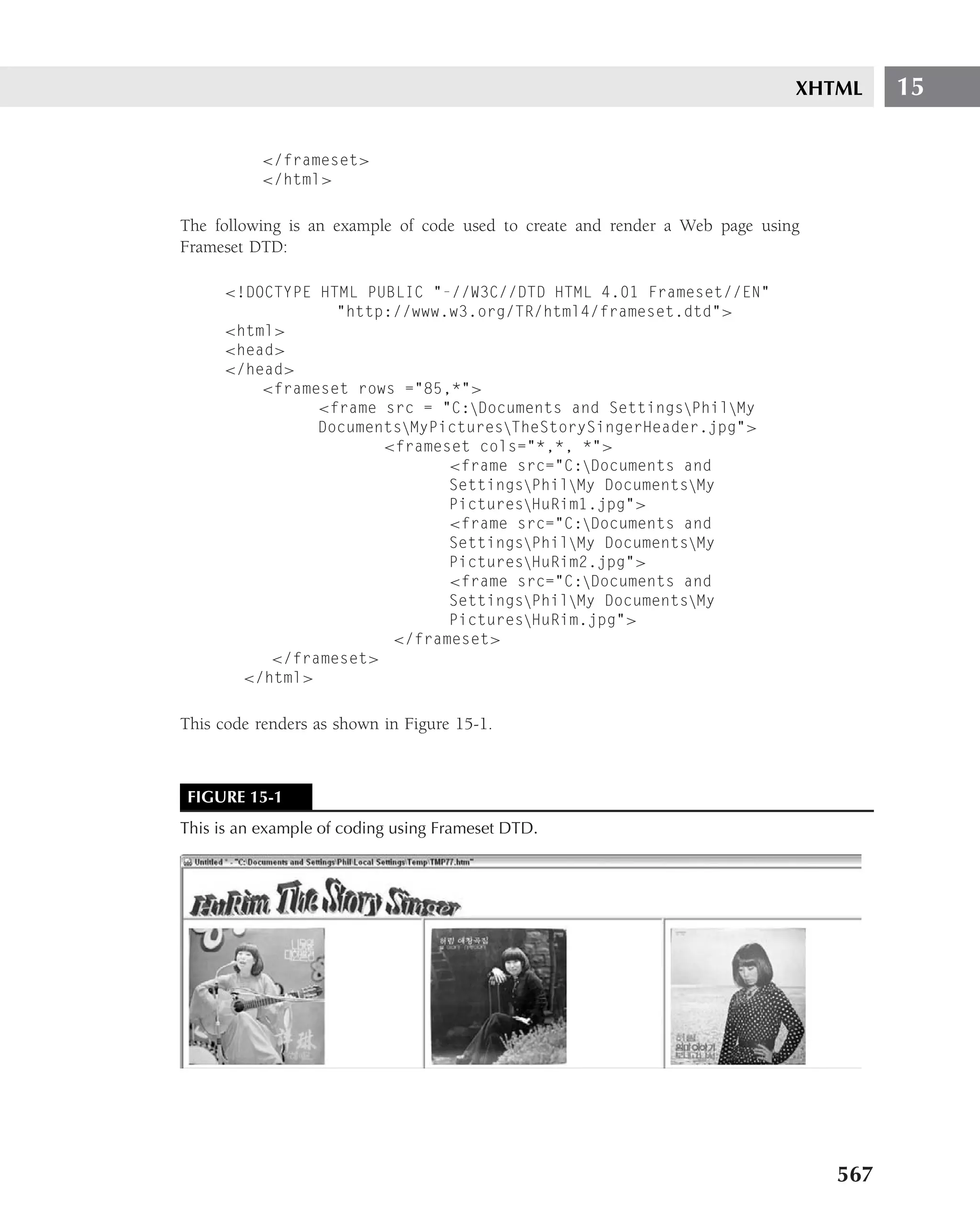

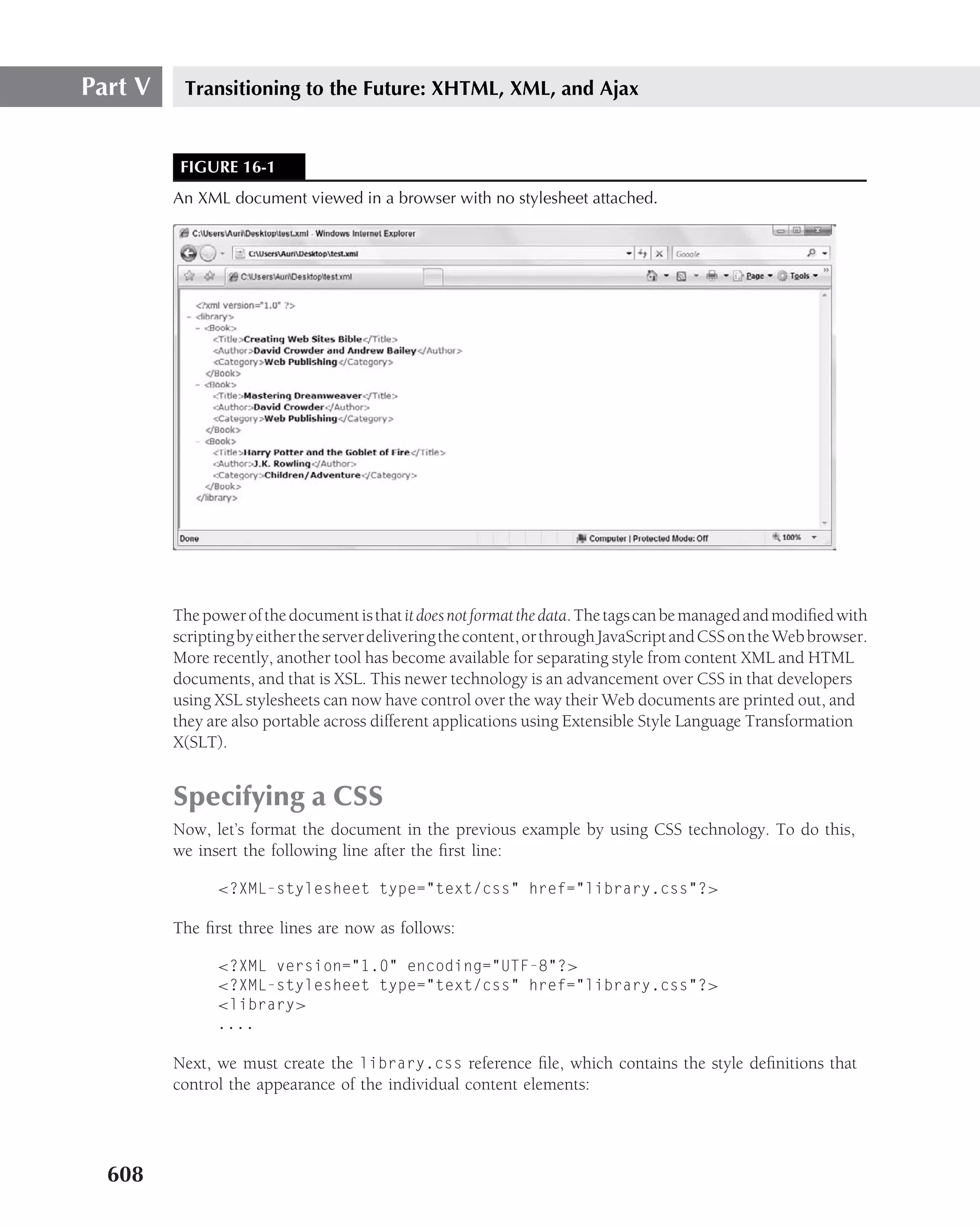

Following is the same document formatted in XML using Microsoft Word to create it and then

saving the document as an XML document type. We have omitted monumental parts of it, but

we just wanted to give you a better sense of the coding.

<html xmlns:v="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:vml"

xmlns:o="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office"

xmlns:w="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:word"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40">

<head>

<meta http-equiv=Content-Type content="text/html; charset=us-ascii">

<meta name=ProgId content=Word.Document>

<meta name=Generator content="Microsoft Word 11">

<meta name=Originator content="Microsoft Word 11">

<link rel=File-List href="DB5C578F files/filelist.xml">

<link rel=Edit-Time-Data href="DB5C578F files/editdata.mso">

<!--[if !mso]>

<style>

v:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

o:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

w:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

.shape {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

</style>

<![endif]-->

<title>Sample case or switch structure</title>

<!--[if gte mso 9]><xml>

</o:shapelayout></xml><![endif]-->

</head>

Note that the preceding code completes the <head> structure. The <body> has several divisions

<div> in it to distinguish the sections, and, of course, each section has the standard HTML block

elements of <p> and other tag identifiers (such as span and class). In the following code, the

<table> structure with multiple <tr> and <td> is also used:

<body lang=EN-US style=’tab-interval:.5in’>

<div class=Section1>

<p class=MsoTitle>Sample case or switch structure</p>

<p class=MsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p>

<p class=MsoNormal>Int gradeLevel;</p>

614](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-650-2048.jpg)

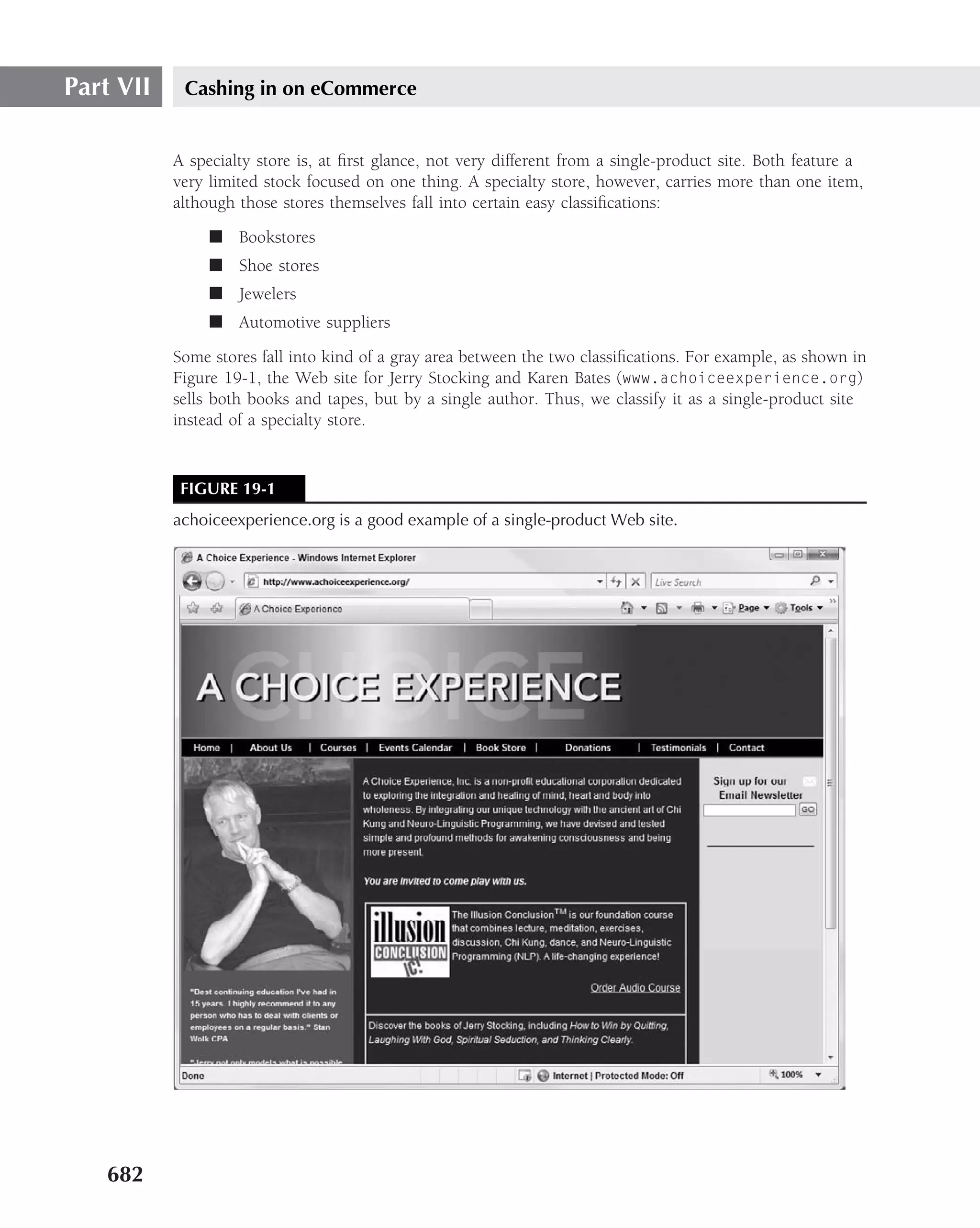

![Designing with XML 16

style=’position:absolute;

z-index:2’ from="1in,1.85pt" to="1in,19.85pt">

<v:stroke endarrow="block"/>

</v:line><![endif]--><![if !vml]><span style=’mso-ignore:vglayout’>

<table cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 align=left>

<tr>

<td width=90 height=1></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td><img width=12 height=27 src="DB5C578F files/image002.gif"

v:shapes=" x0000 s1028"></td>

</tr>

</table>

</span><![endif]><o:p> </o:p></p>

<br style=’mso-ignore:vglayout’ clear=ALL>

</div>

</body>

</html>

You might remember that a big advantage of a case structure over a nested if

structure is efficiency.

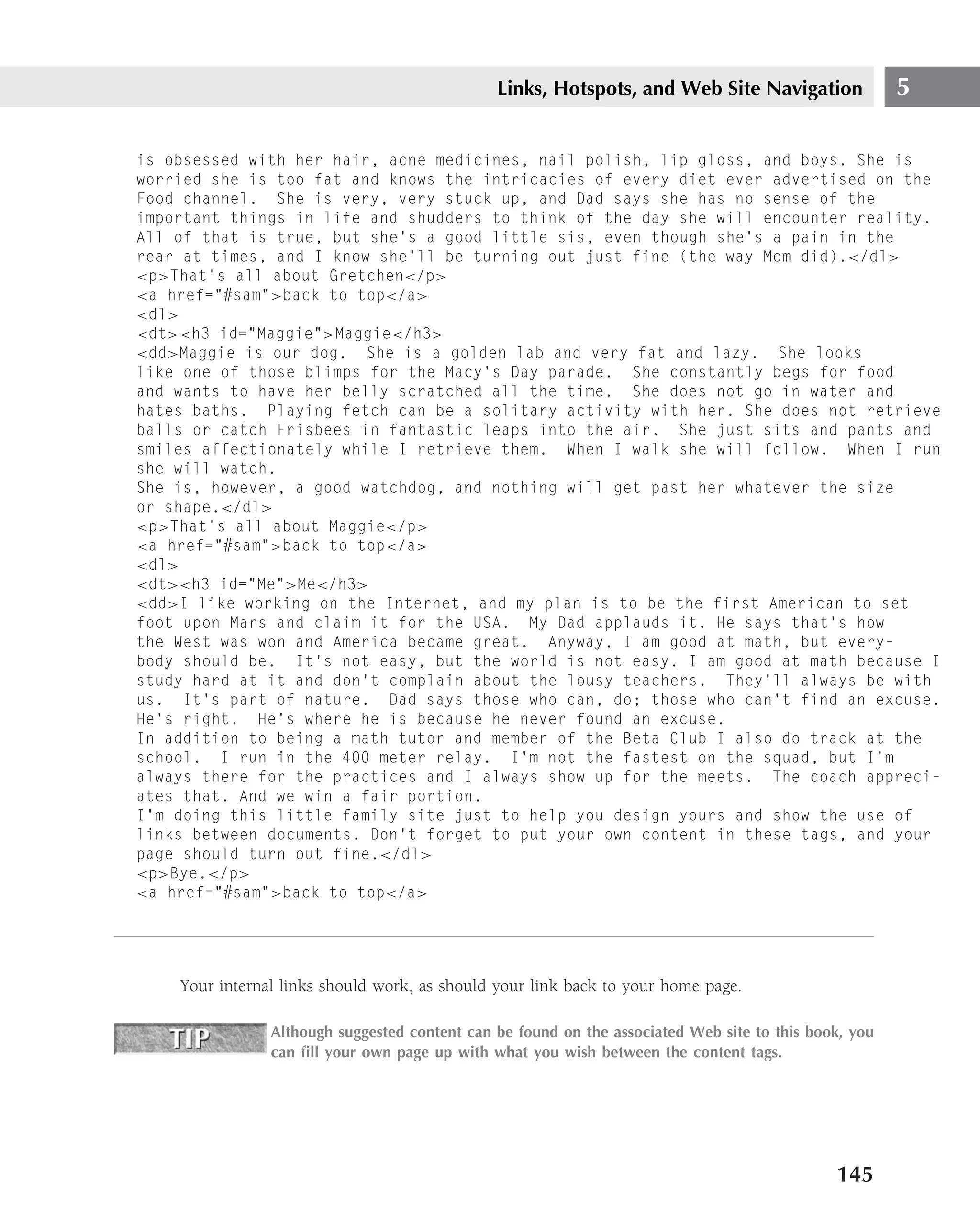

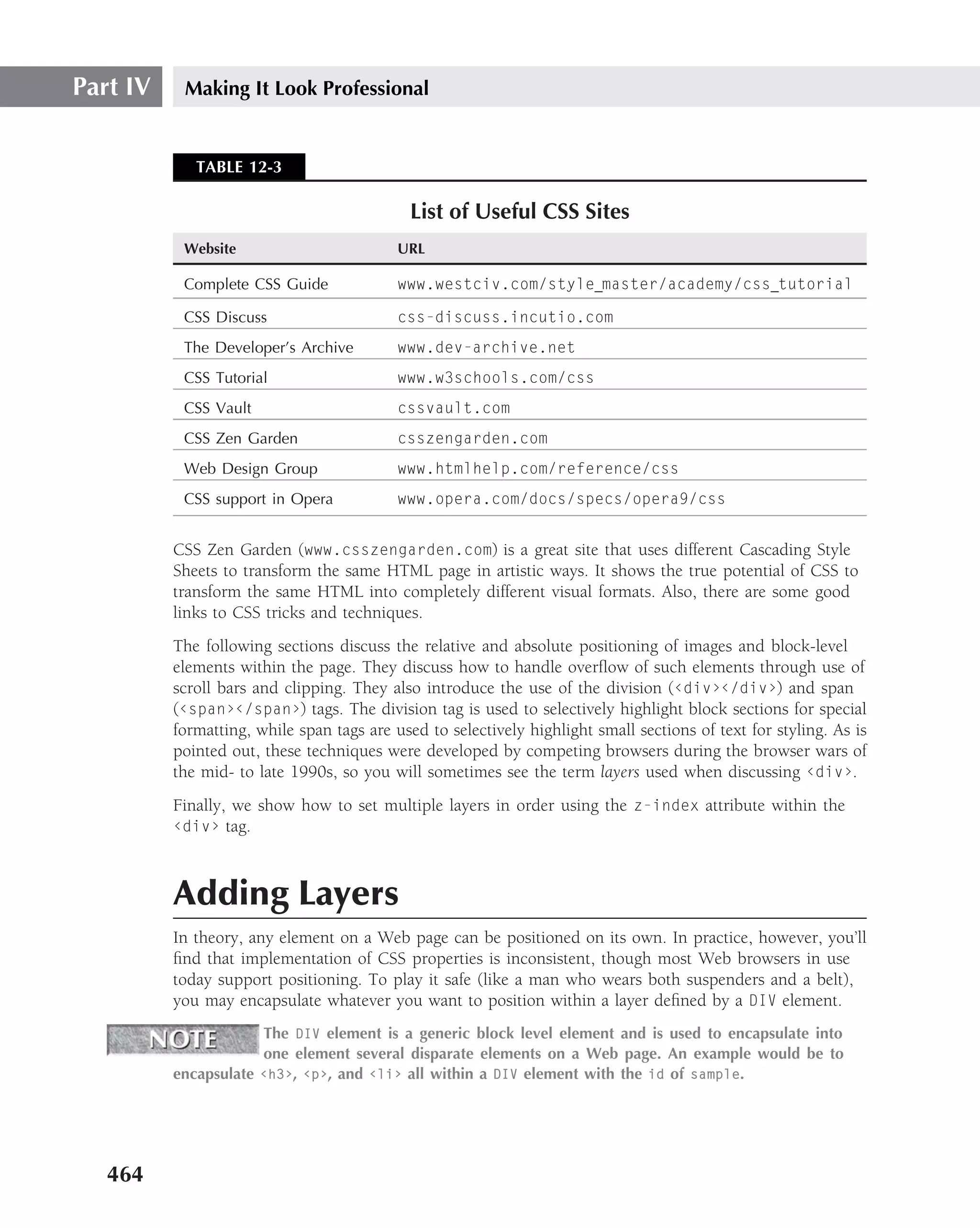

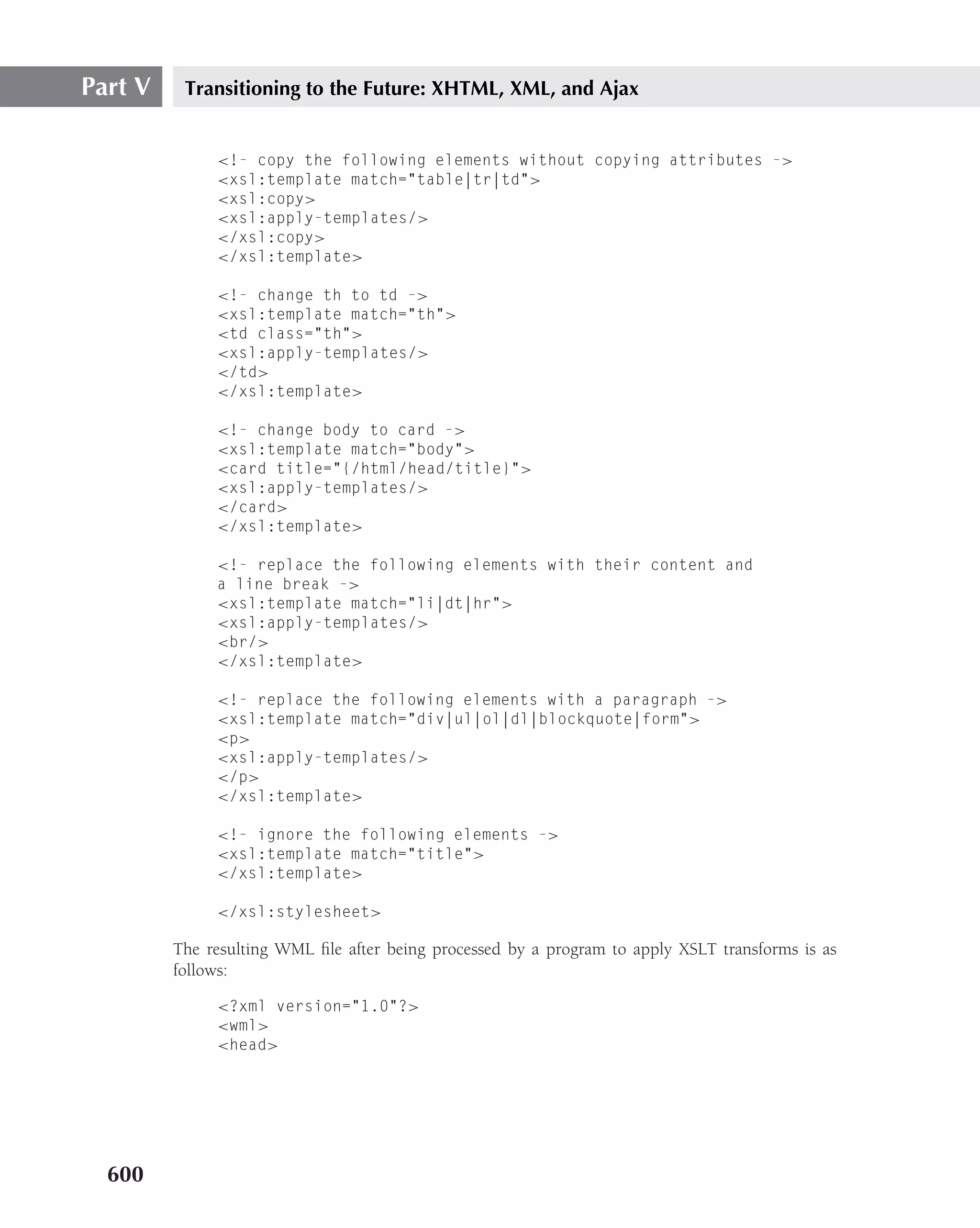

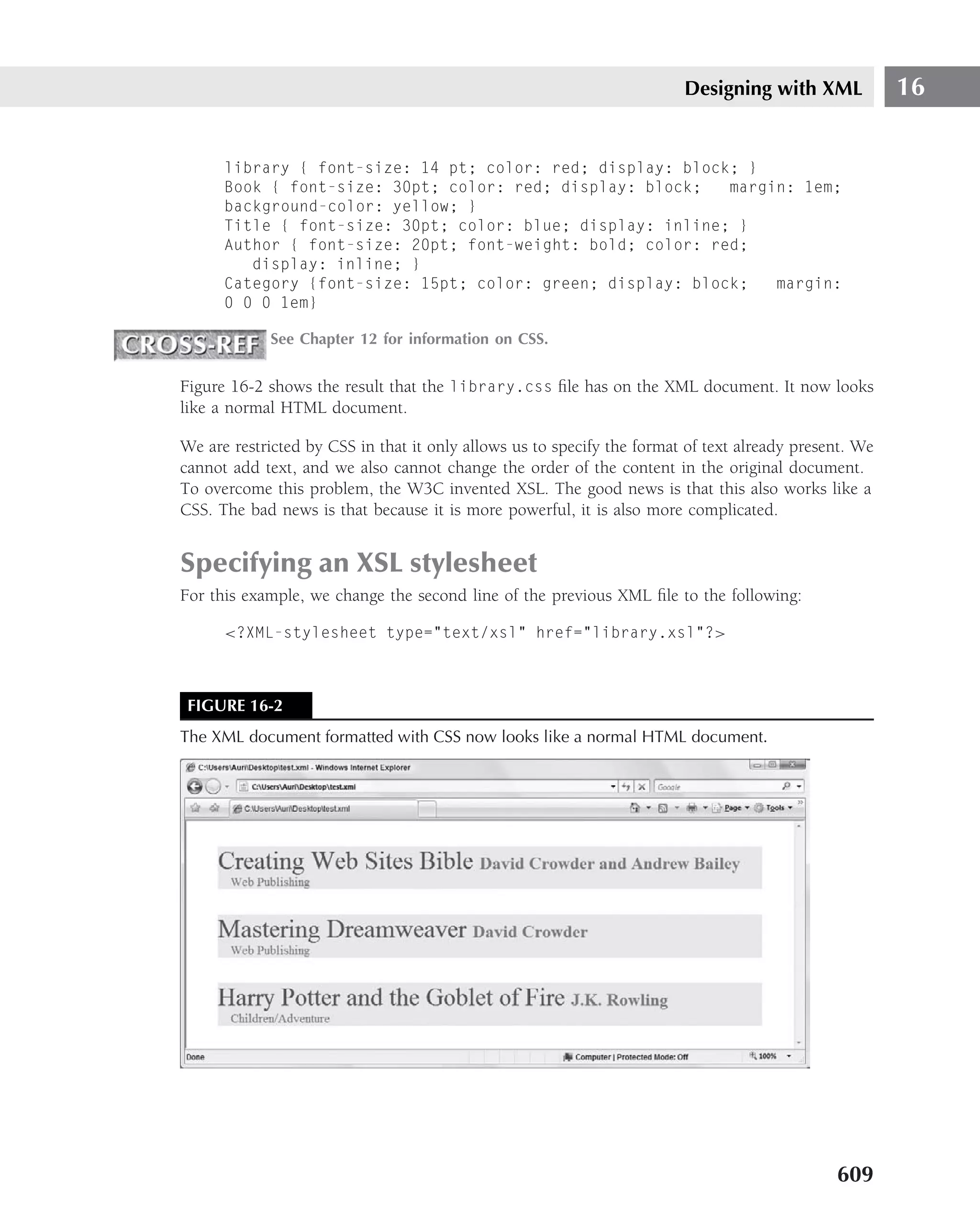

XSL is very complicated at first sight, because it uses a different concept of programming. Tak-

ing a page from object-oriented programming (OOP), you might call this type of programming

template-oriented programming.

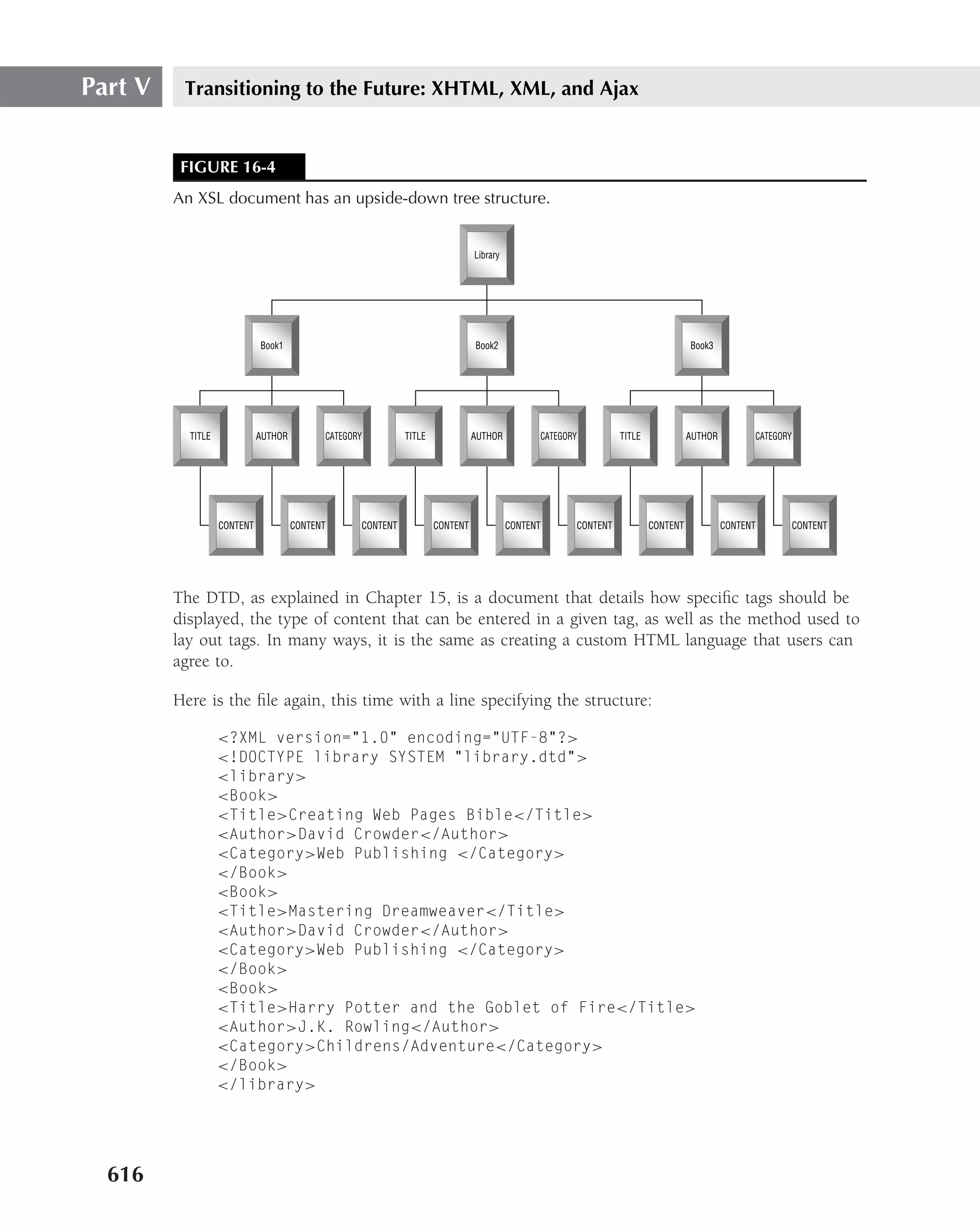

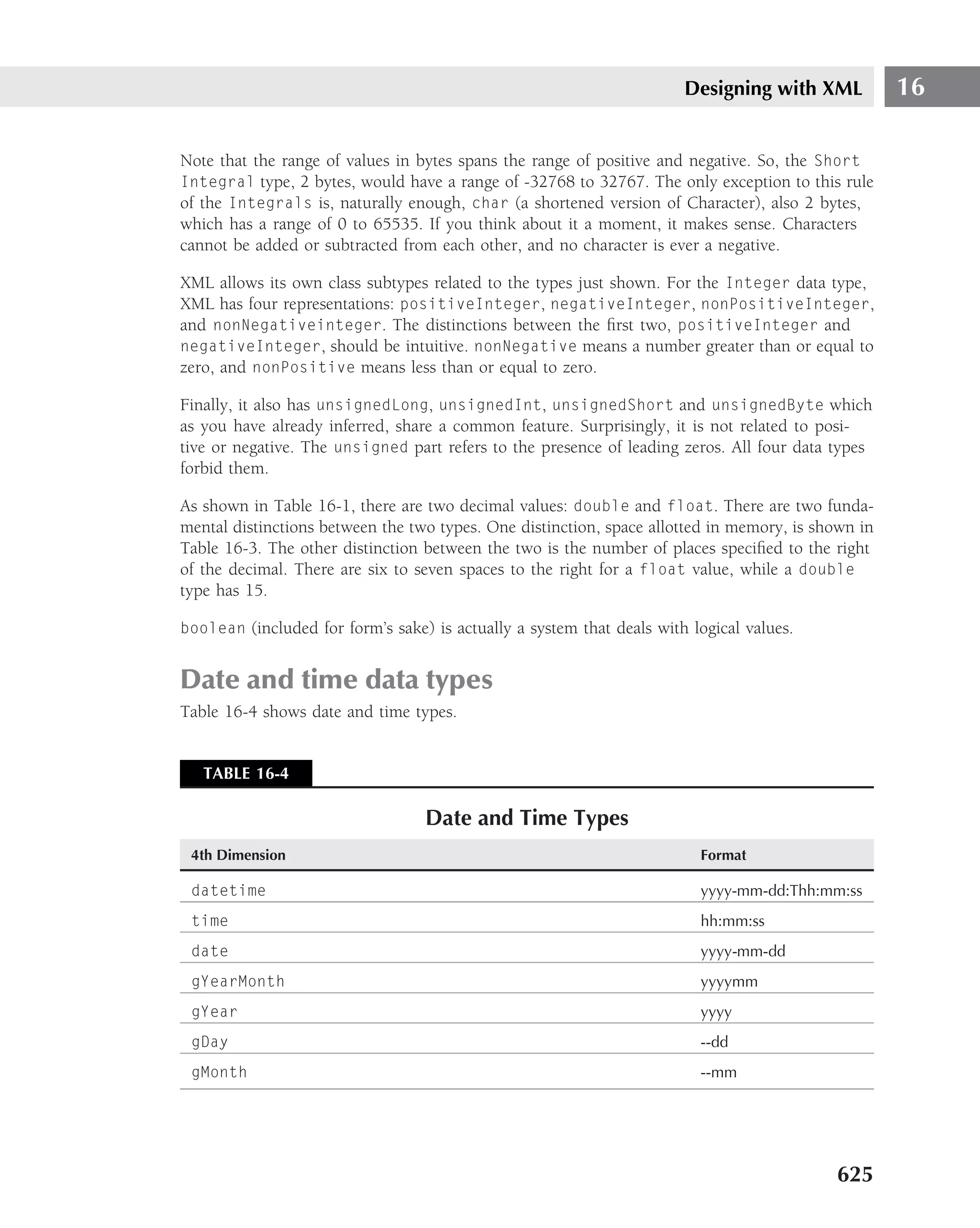

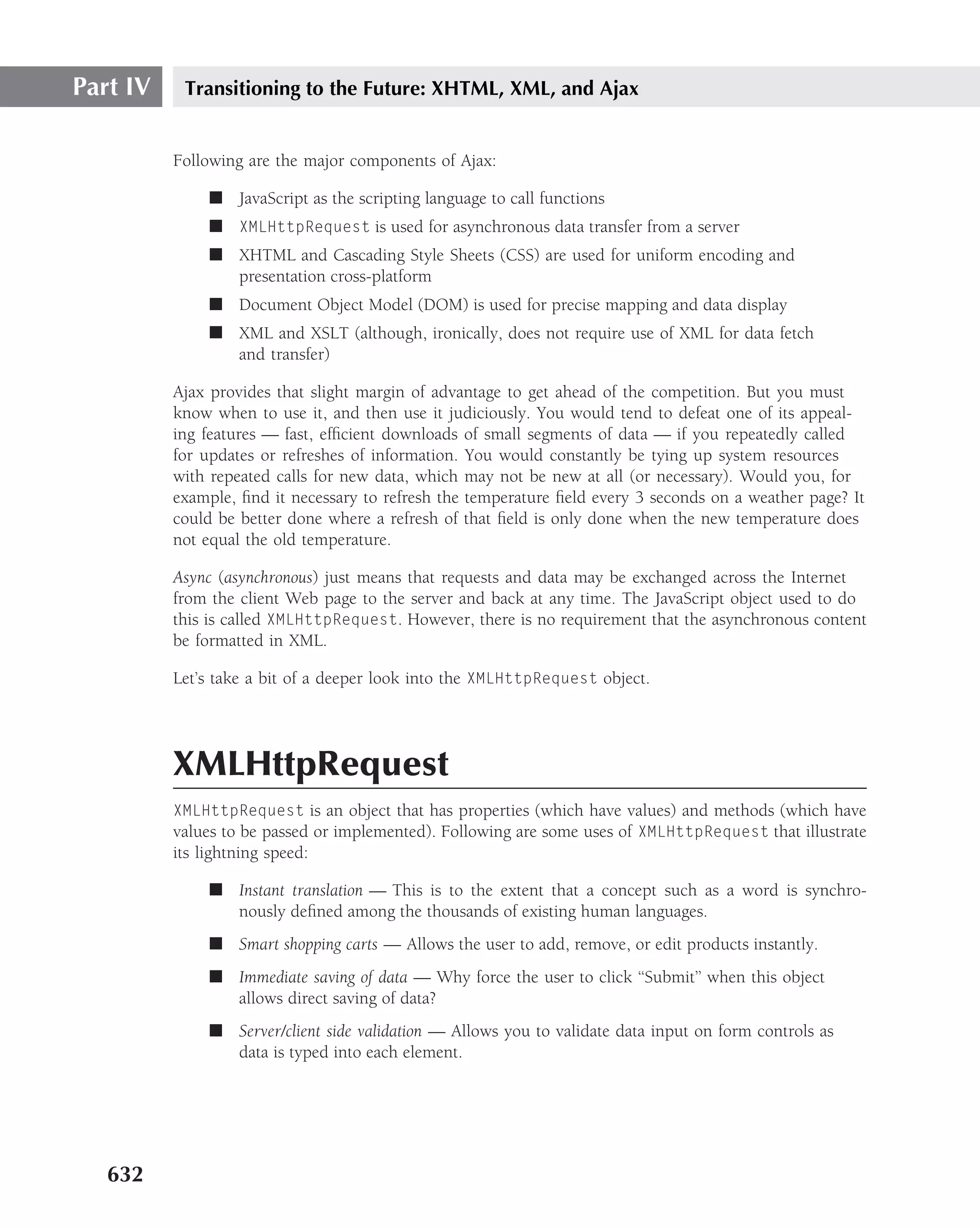

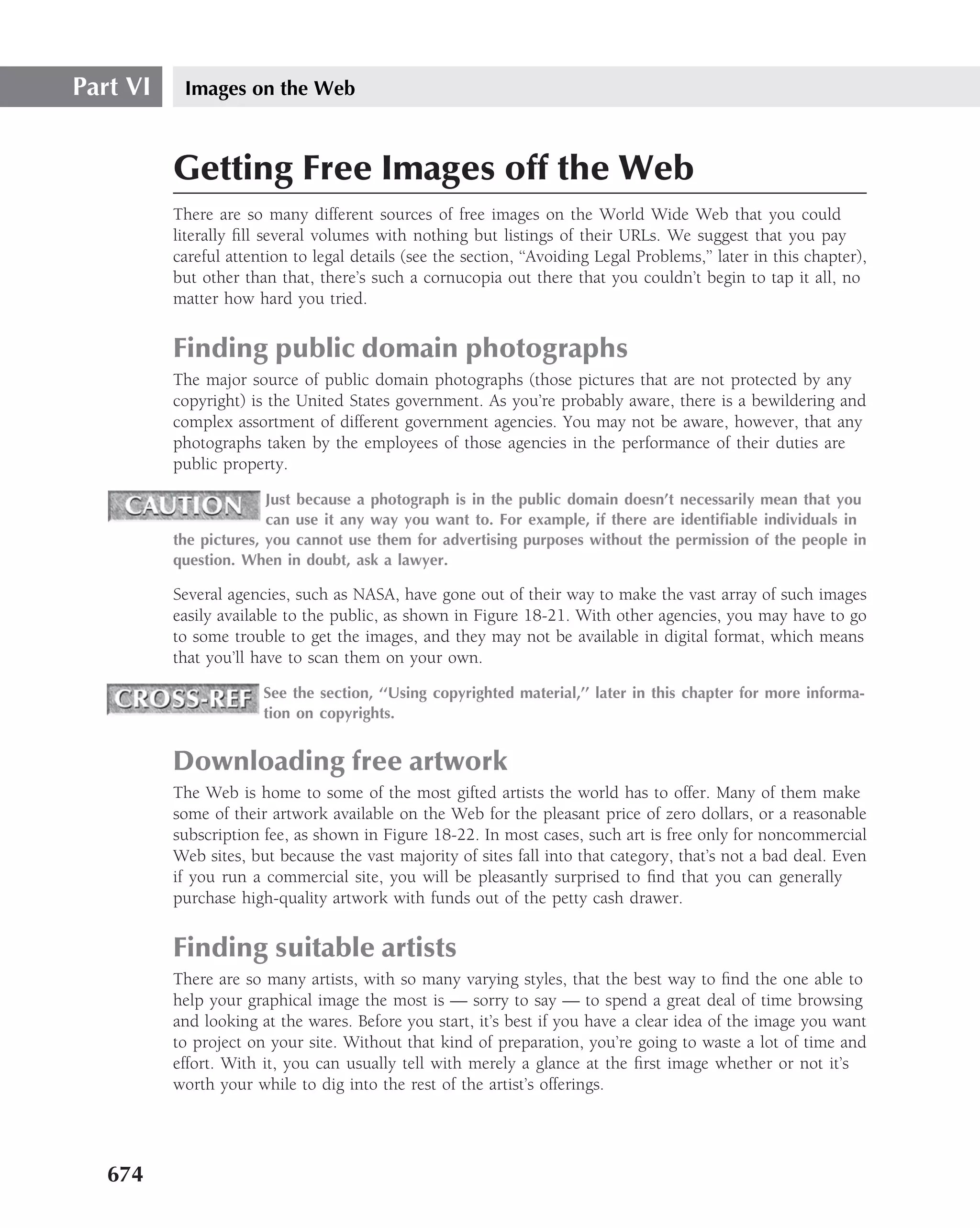

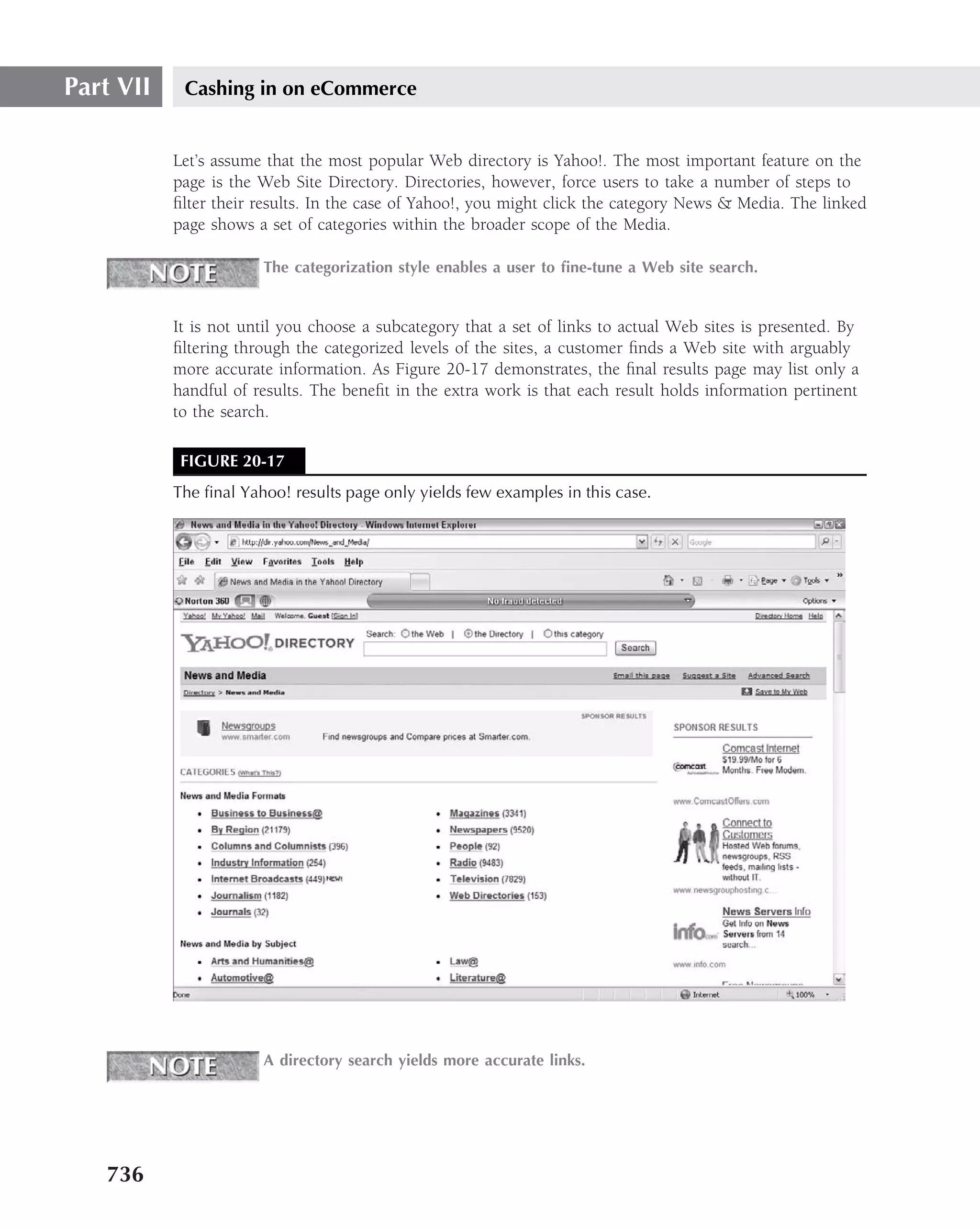

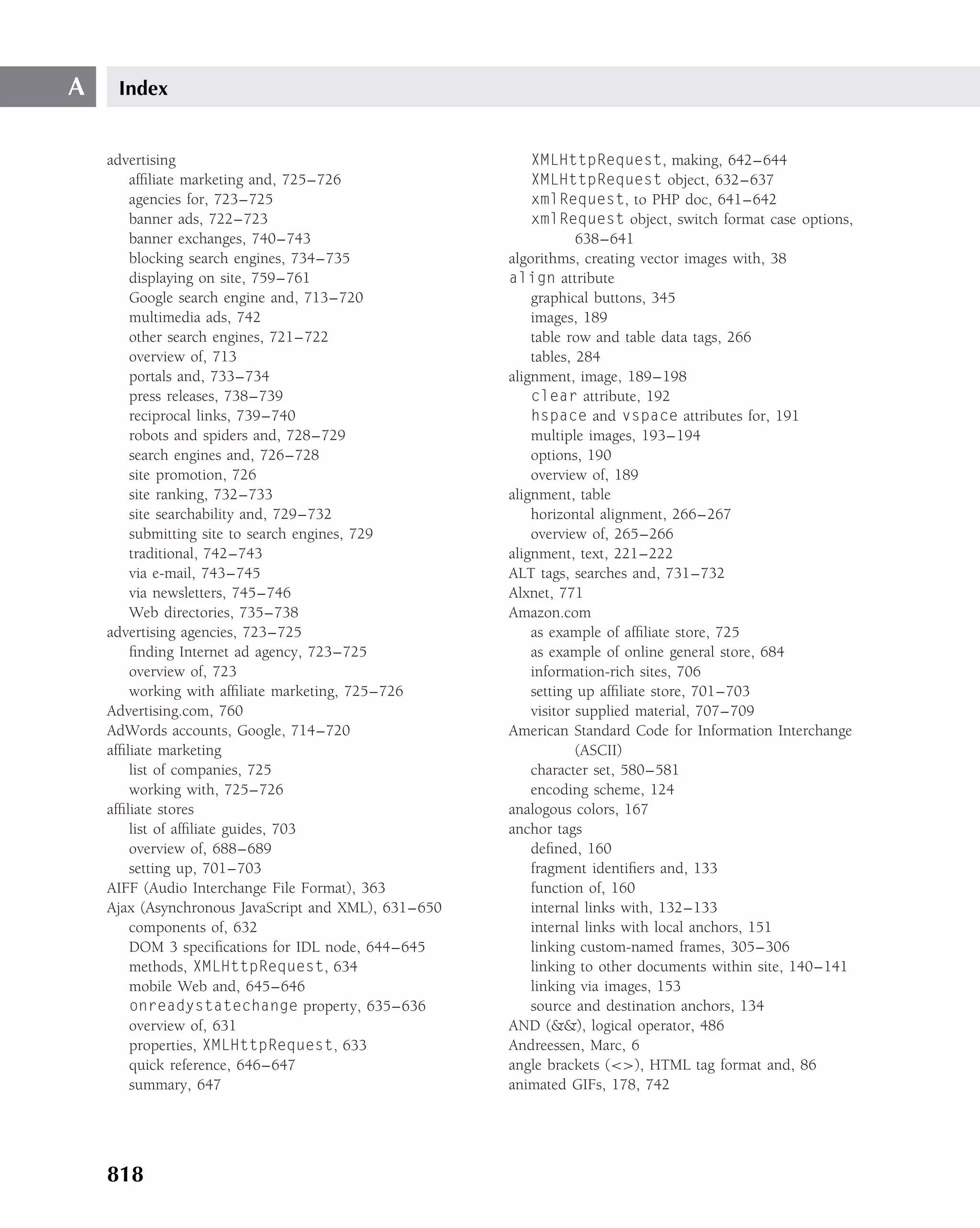

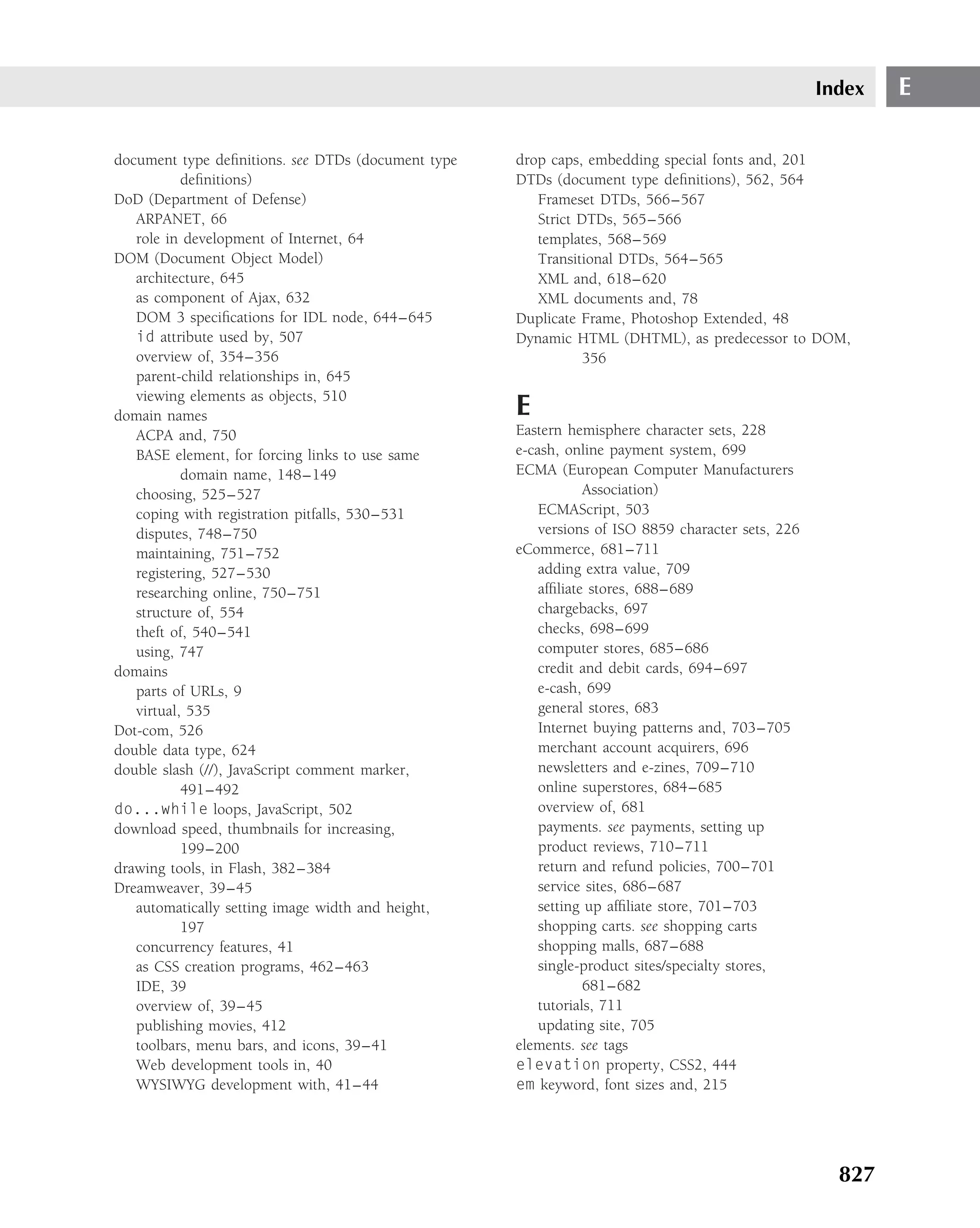

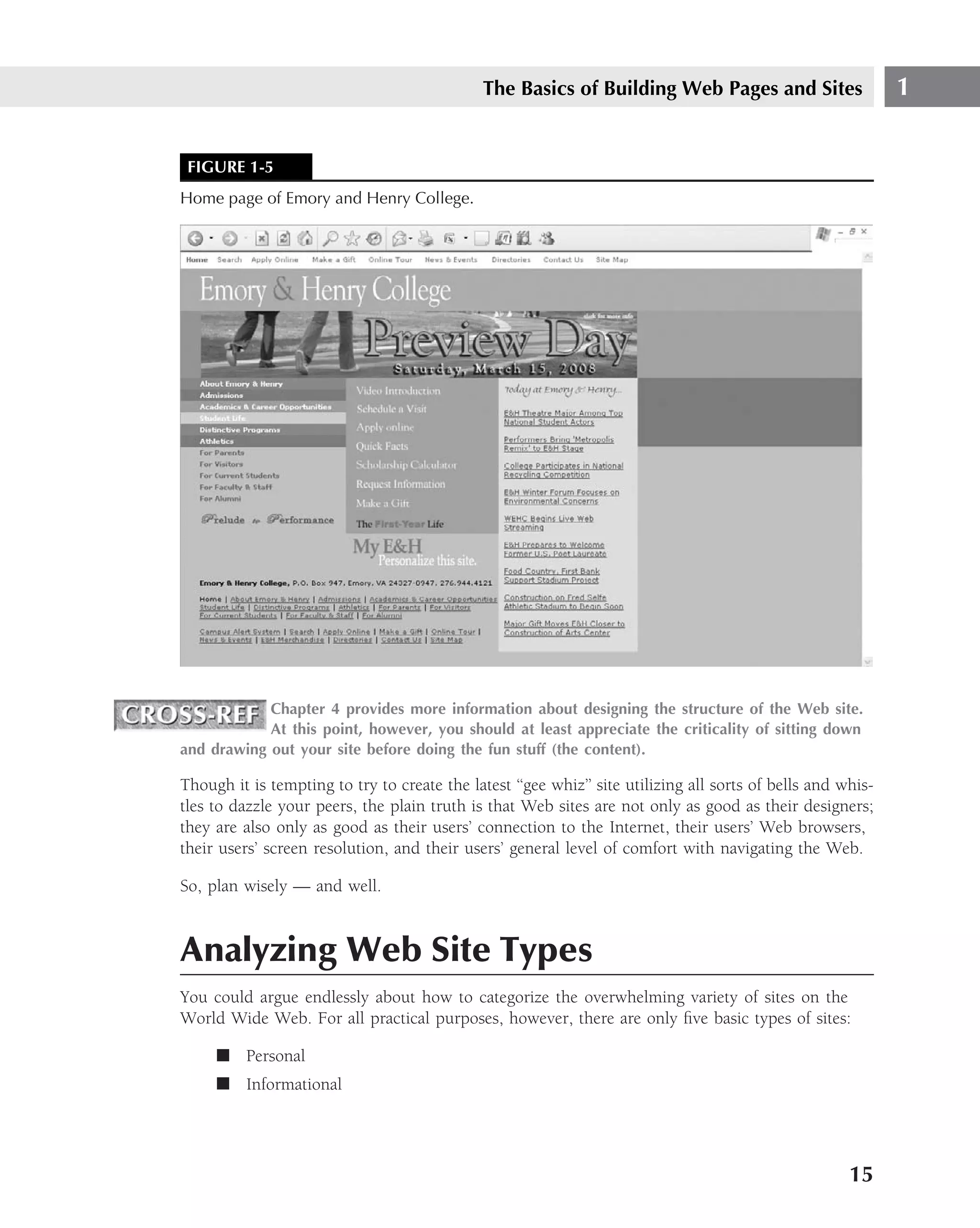

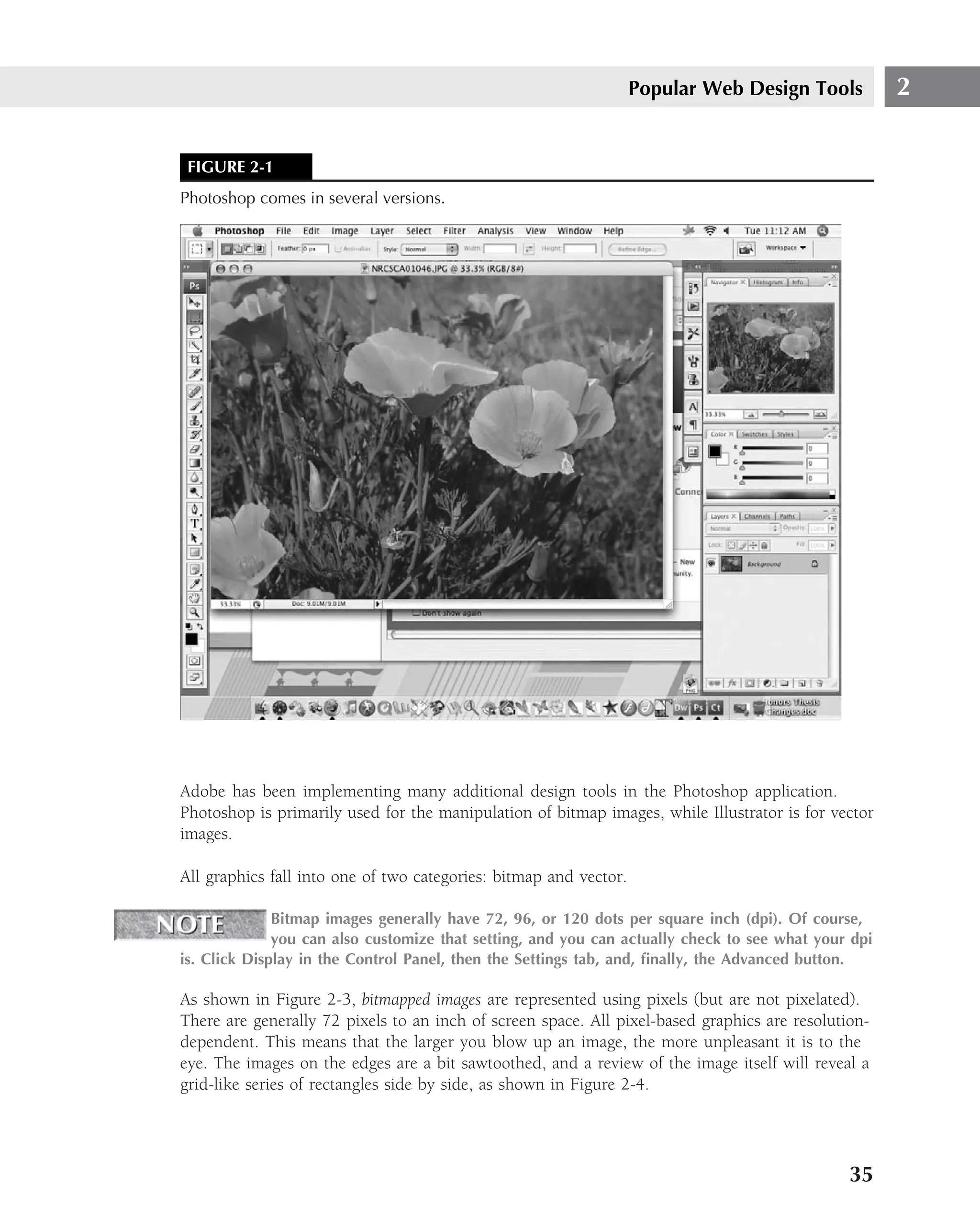

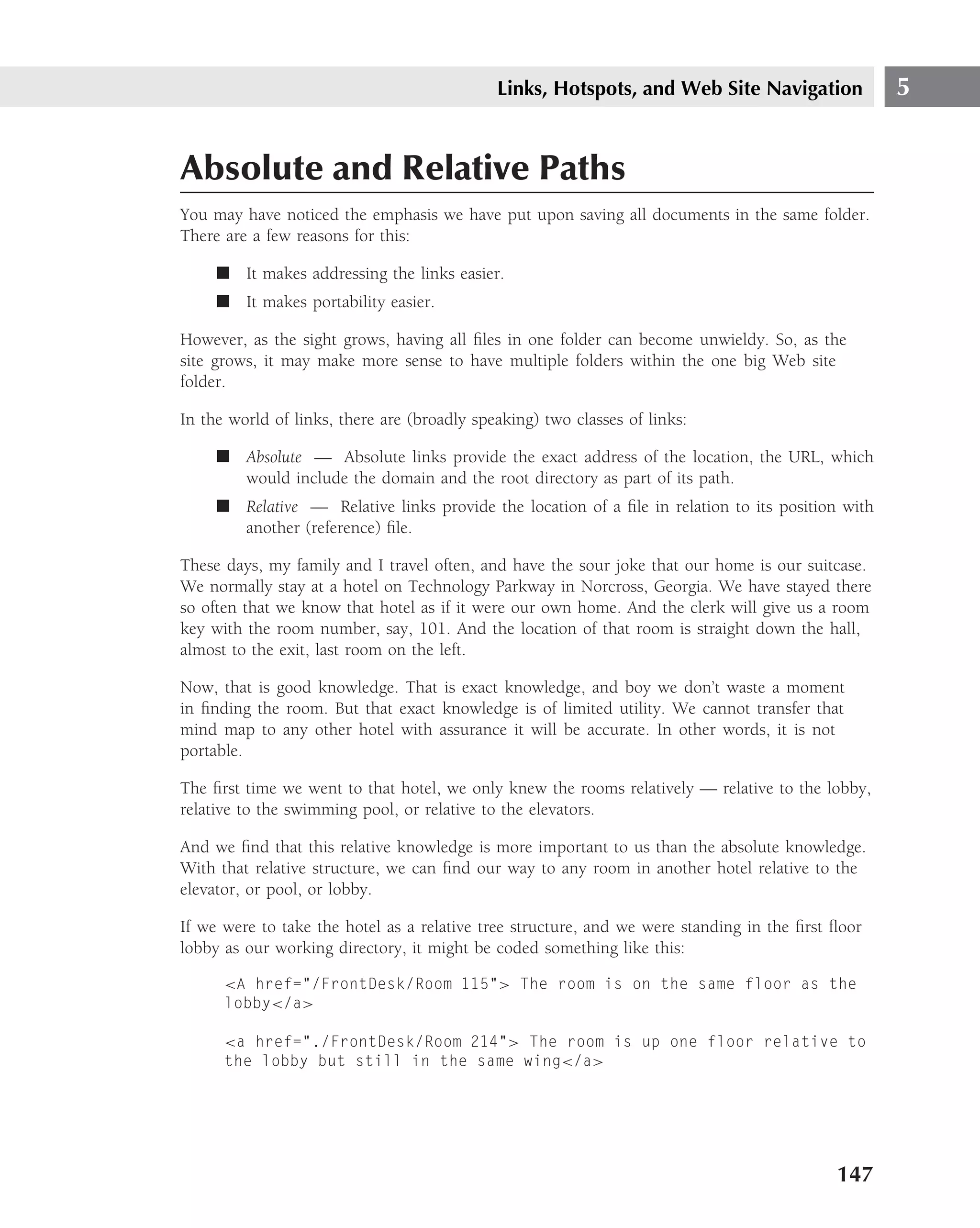

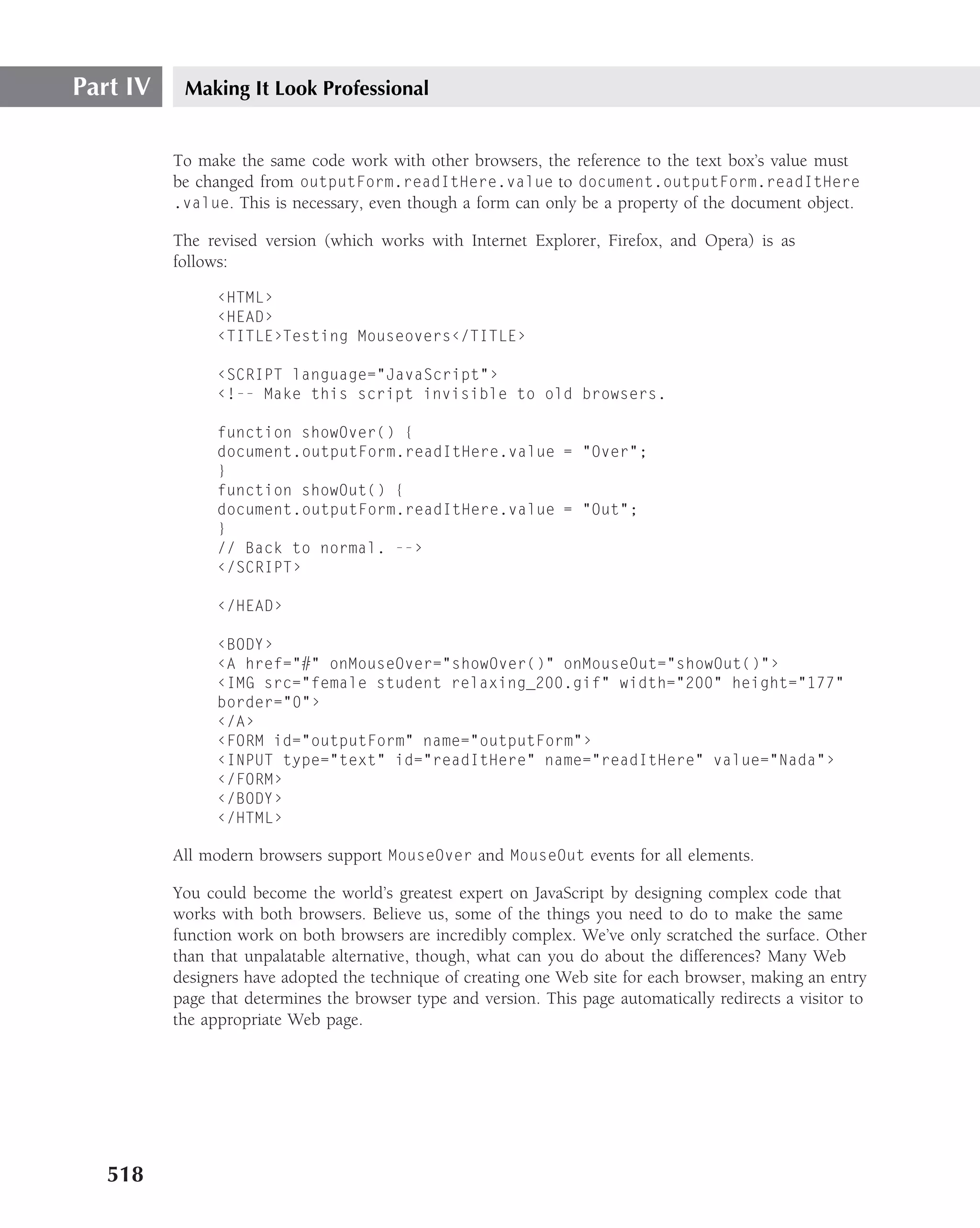

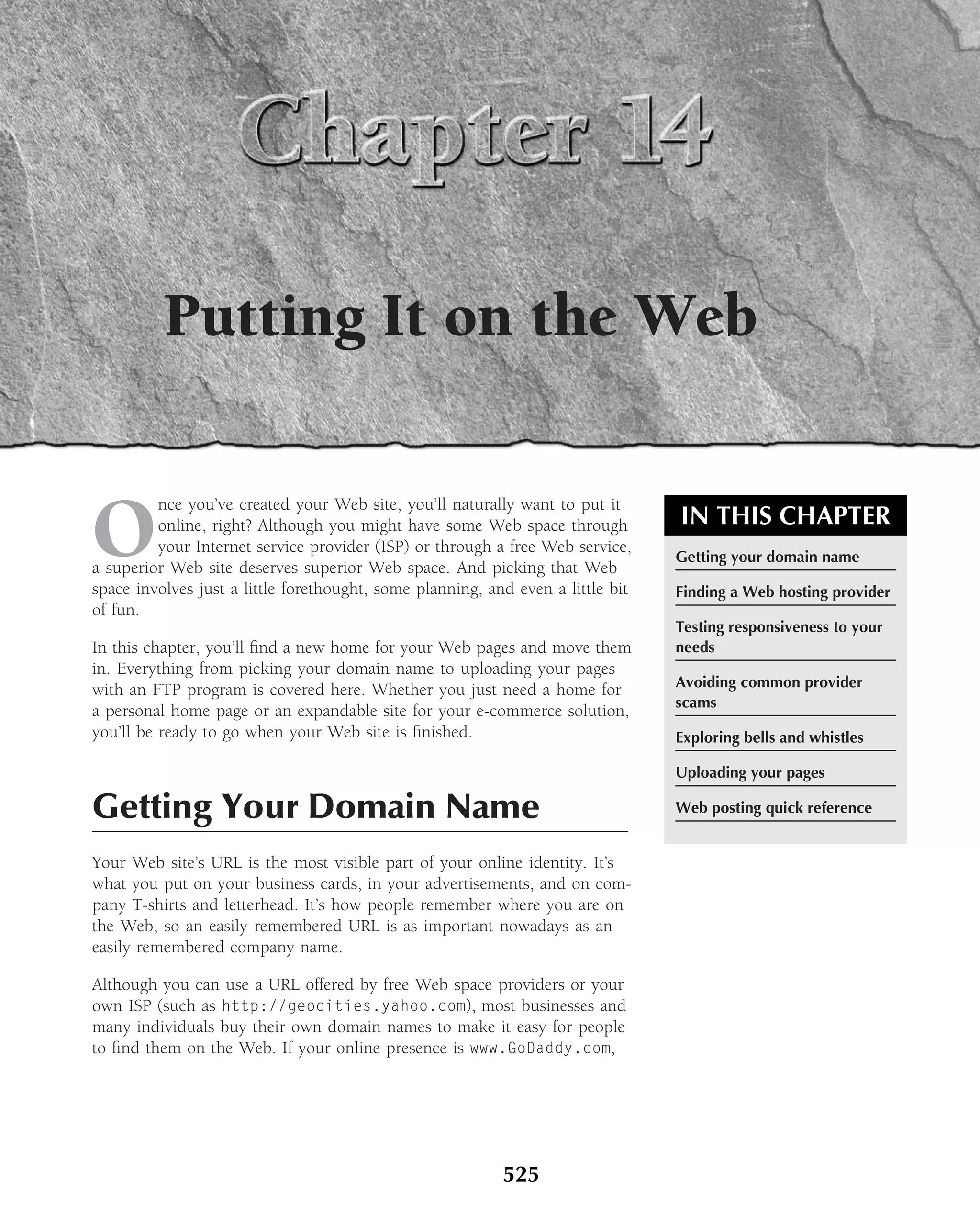

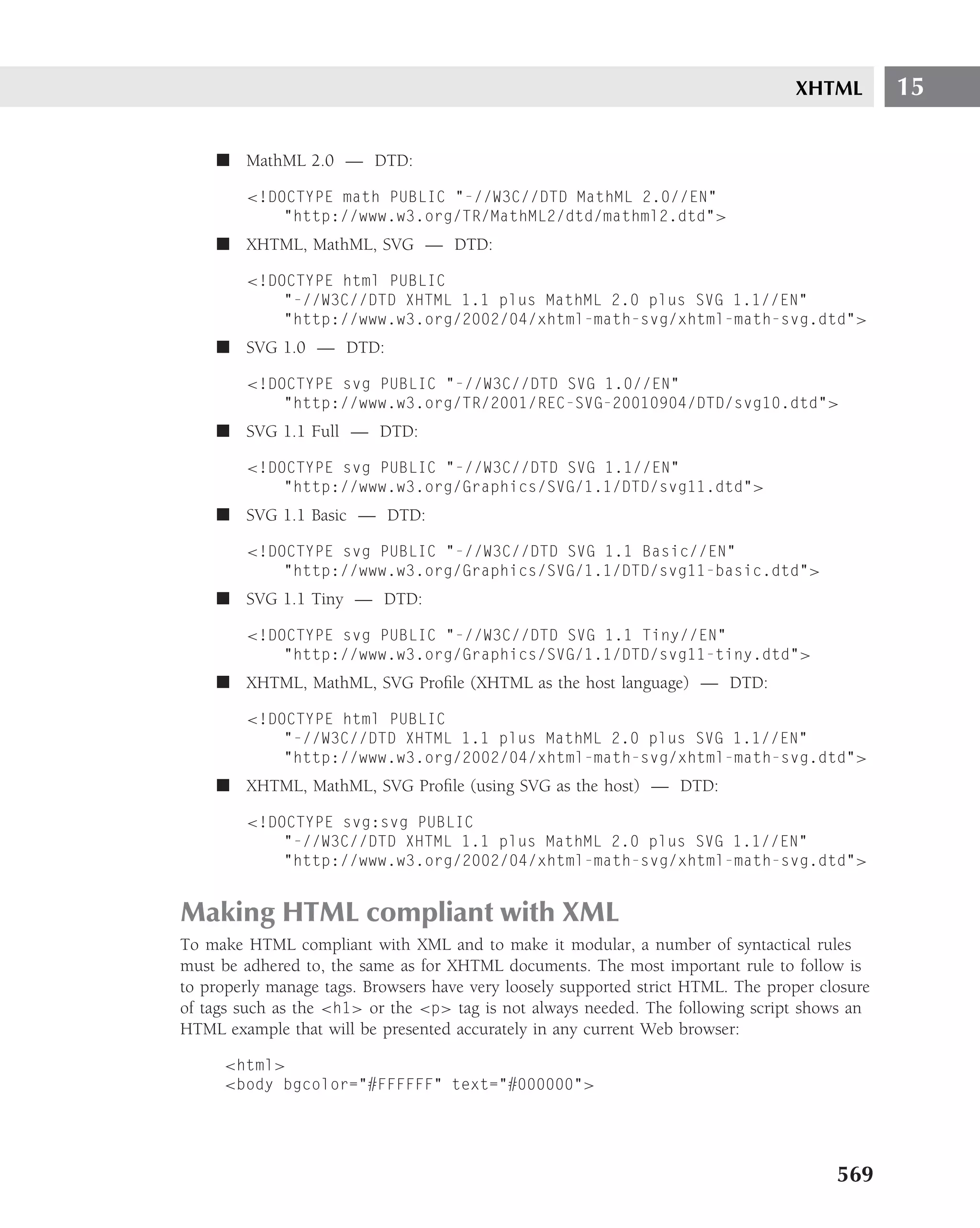

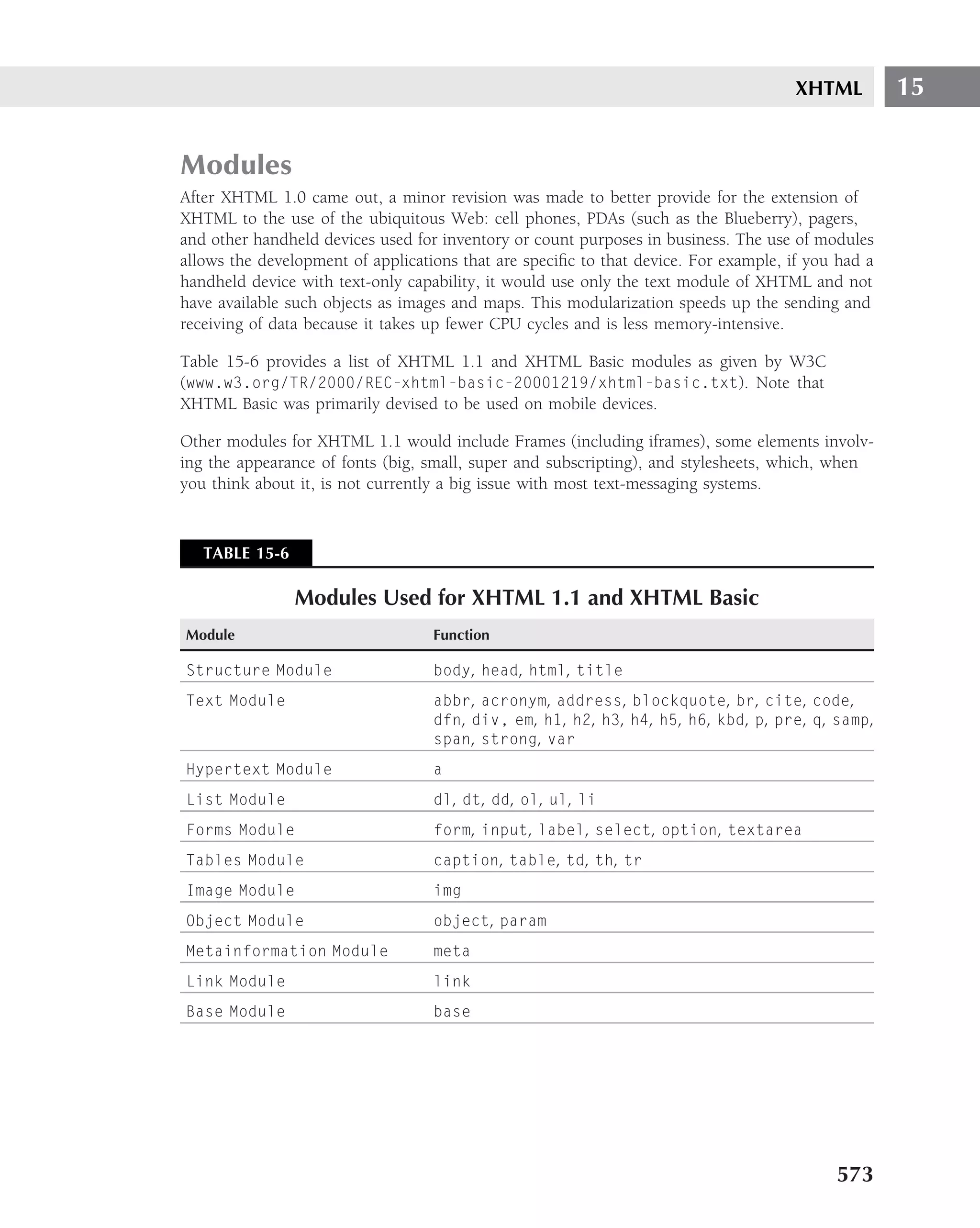

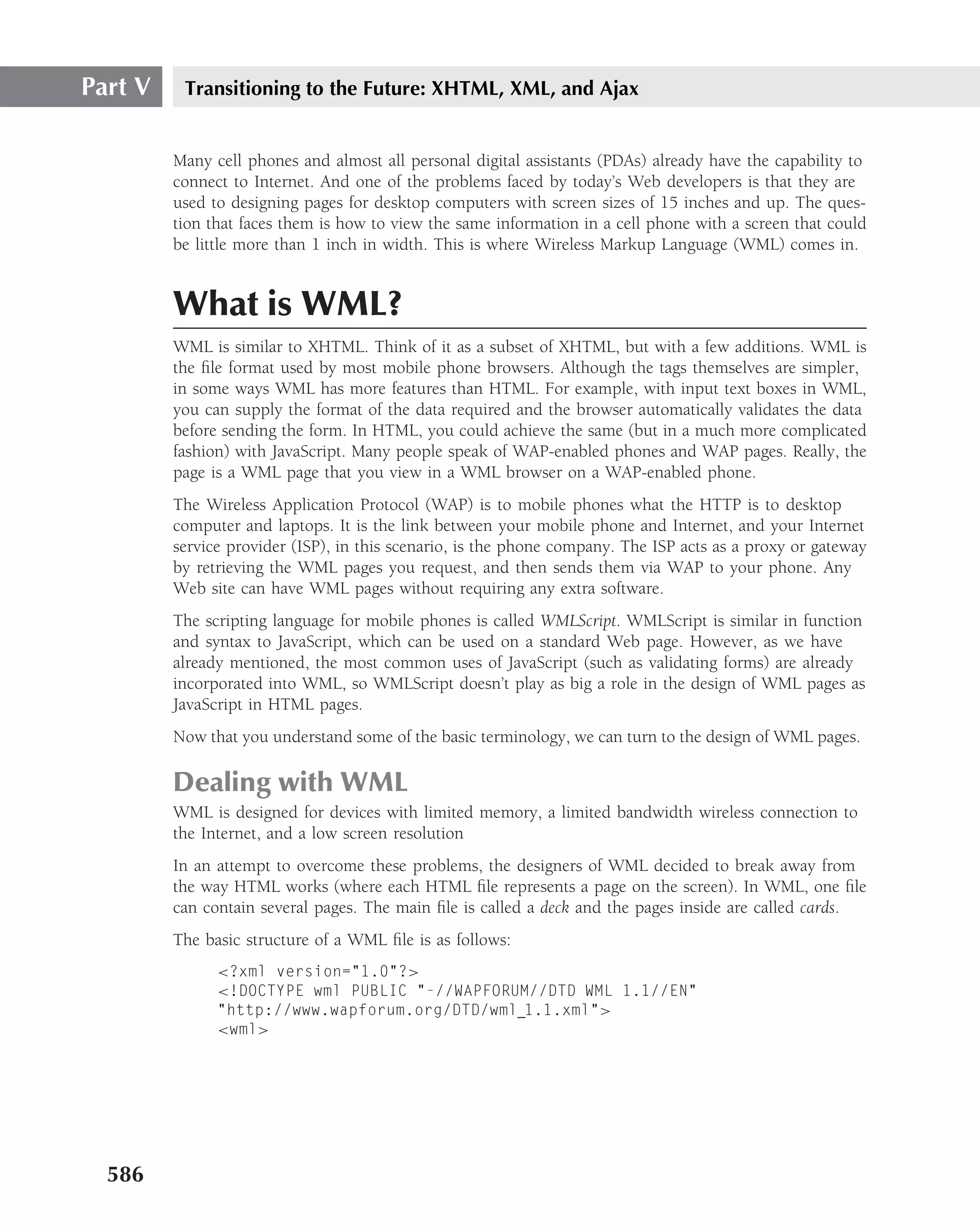

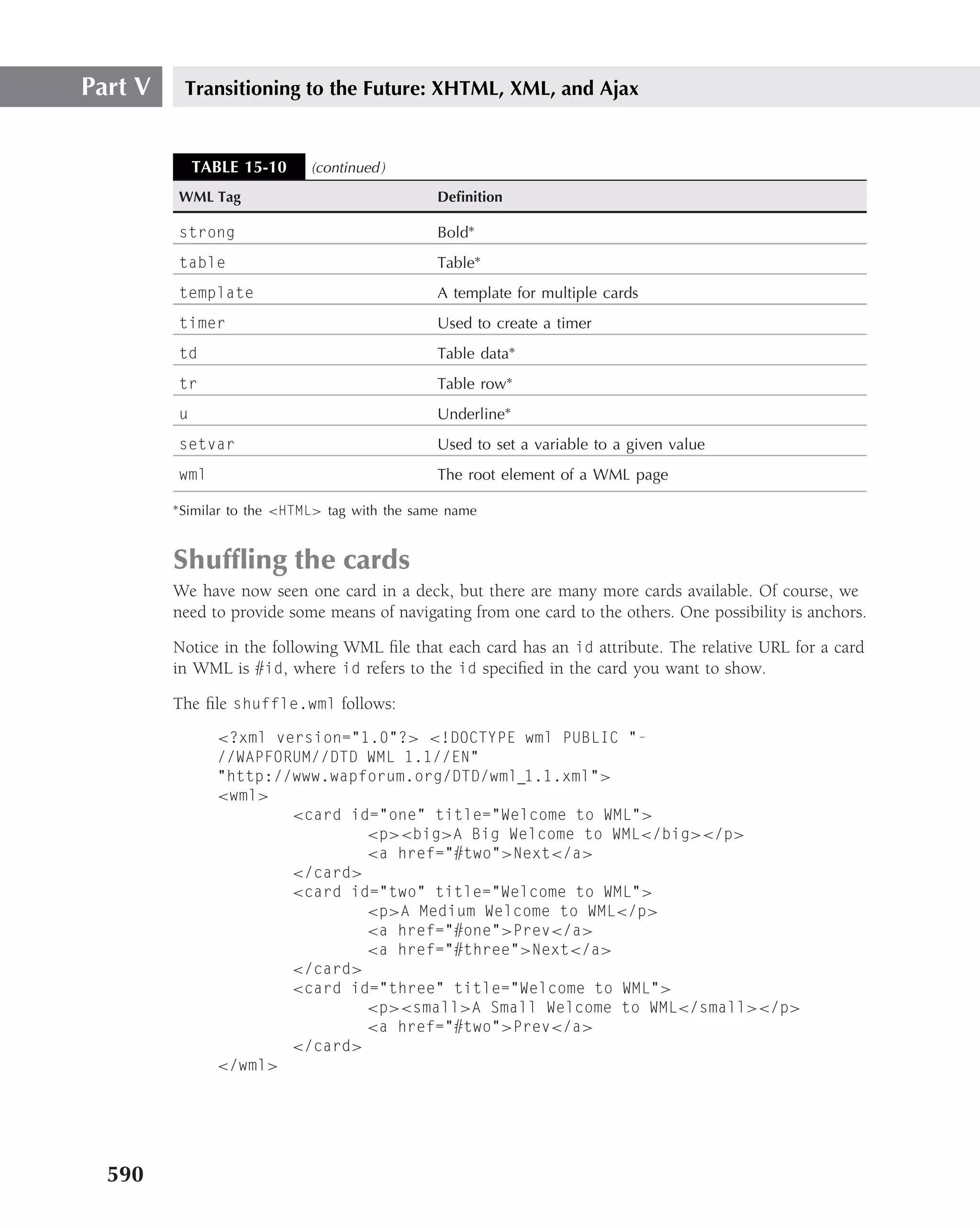

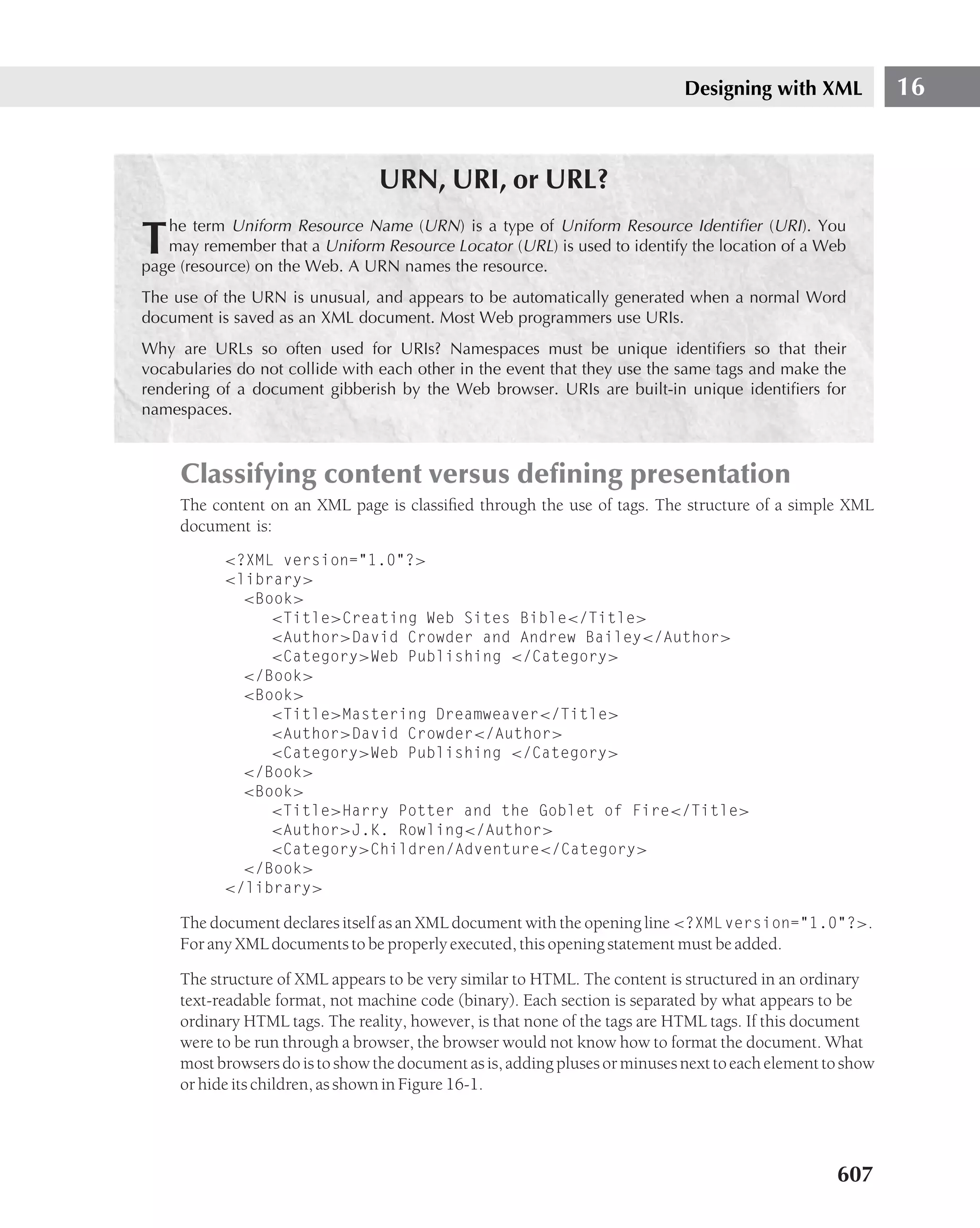

To understand XSL, you must think of an XML document as an upside-down tree with the root

at the top, as shown in Figure 16-4. The tree shown in Figure 16-4 represents the document

structure and, although you cannot see the labels, the color coding represents the top-down

document structure, showing the flow from root: library to the three branches of each book

name (the second row). Derived from each of the three book names are the Title, Author, and

Category of each book (the third row). Subordinate to those (the last row) is the content for

each of the above document nodes.

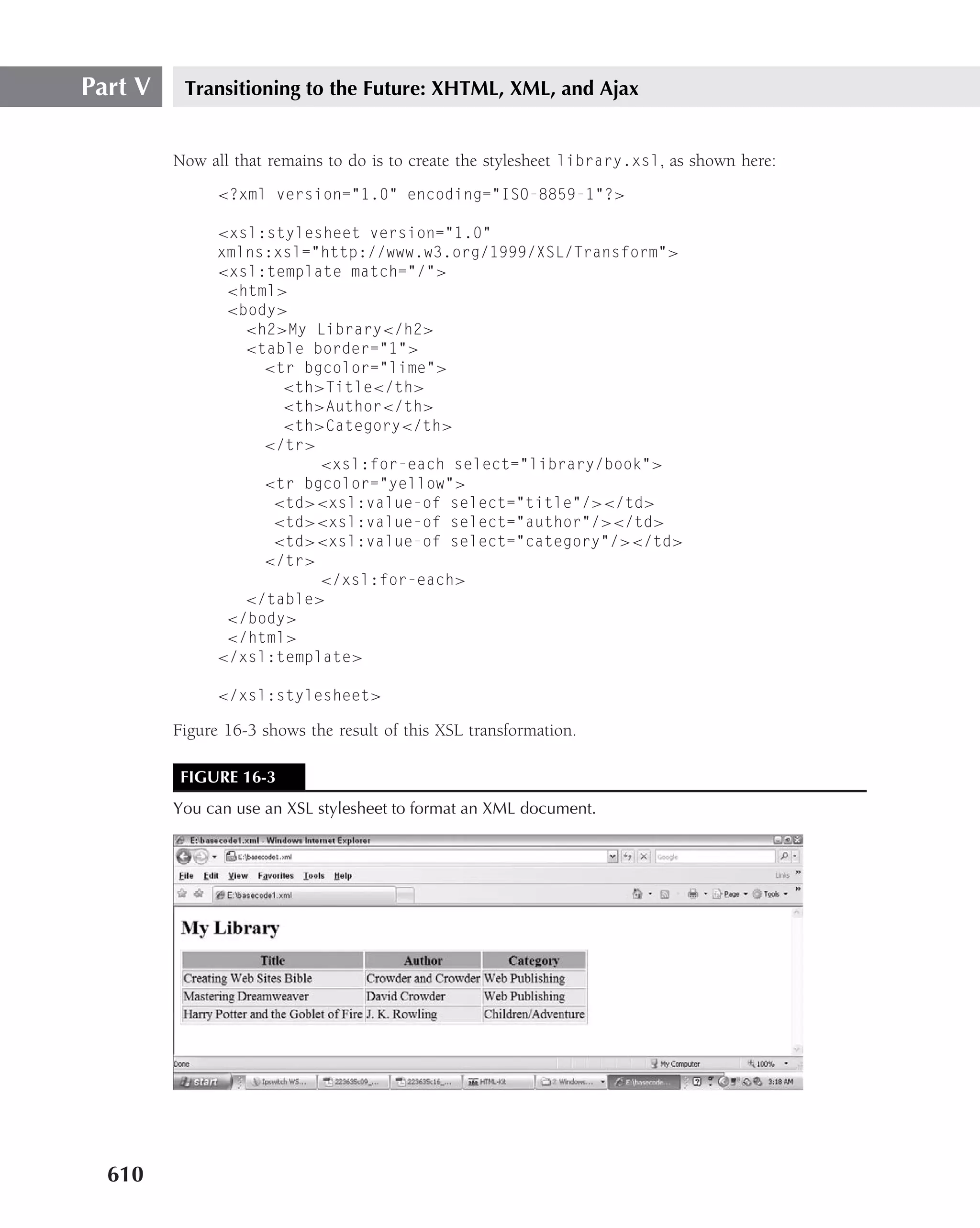

Defining the structure of an XML document

For the stylesheet, library.css, we assumed that the library had books as child elements and

that each book had Title, Author, and Category child elements. If this isn’t the case, then

the stylesheet won’t produce an error — it will just do what it’s instructed to do. For example,

if the library has children that are shelves, which, in turn, contain the book elements, the previous

stylesheet would not show any books, because we instructed it to match only books that are

children of the library element.

How can we define the structure of the document to make sure it is valid? There are two solu-

tions: a DTD or XML Schema. A DTD is much simpler but not as powerful as the XML Schema.

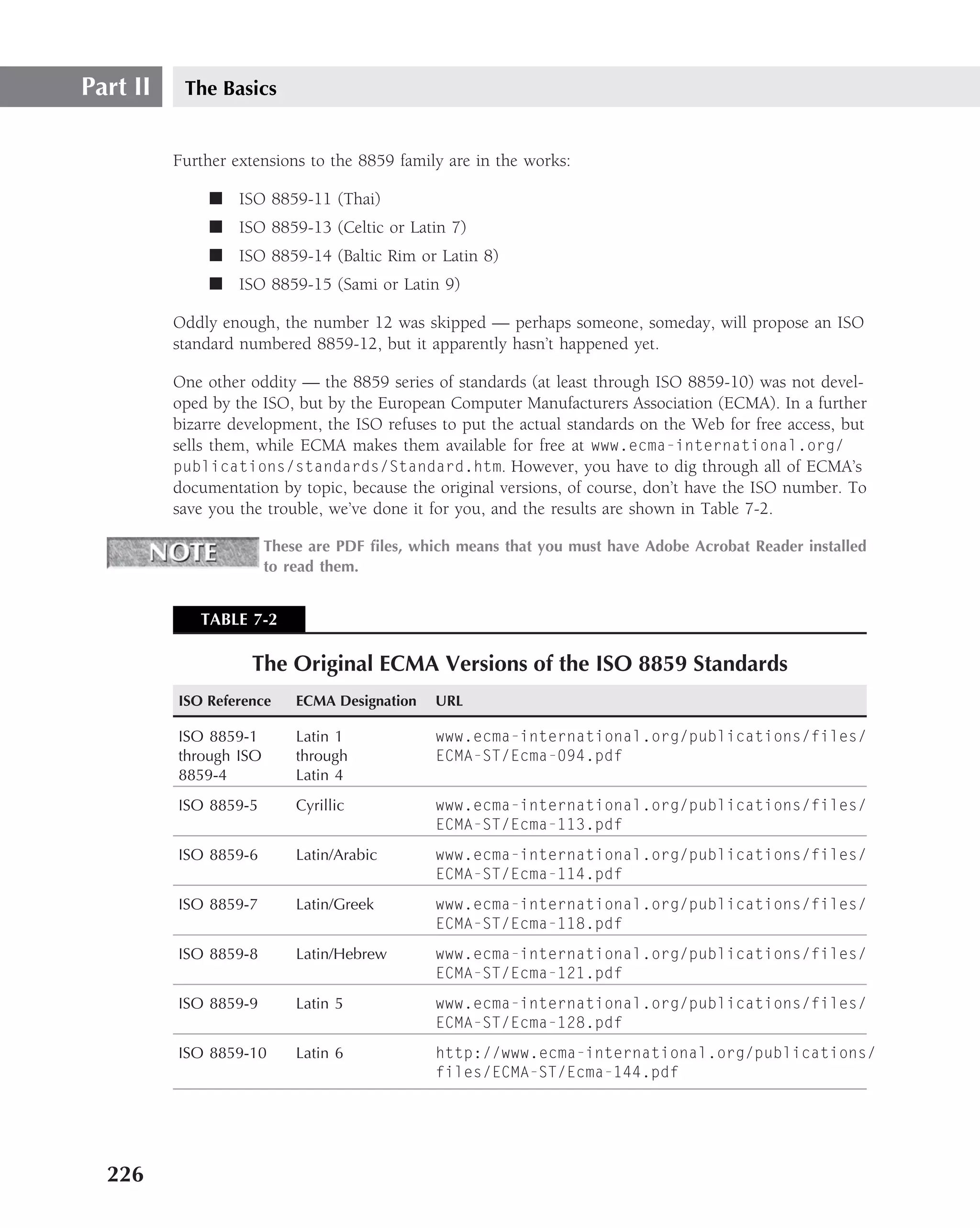

615](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creating-web-sites-bible-jun-2008-100327061205-phpapp01/75/Creating-Web-Sites-Bible-Jun-2008-651-2048.jpg)