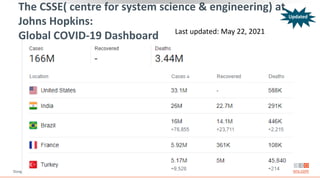

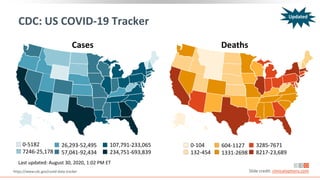

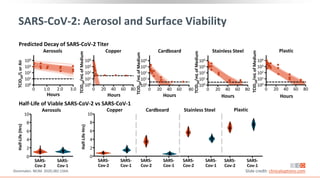

This document provides information on the global epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19. It discusses trends in cases and deaths globally and in the US. It reviews proposed routes of transmission, including via aerosols, droplets, fomites, and the environment. The viability of SARS-CoV-2 on different surfaces is summarized. Prevention strategies like hand washing, social distancing and face coverings are also covered.

![Key Considerations on Modes of SARS-CoV-2

Transmission

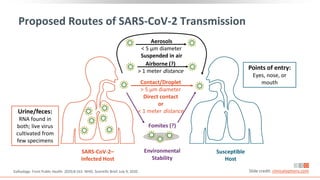

Person-to-person considered predominant mode of transmission, likely via

respiratory droplets from coughing, sneezing, or talking[1,2]

‒ High-level viral shedding evident in upper respiratory tract[3,4]

‒ Airborne transmission suggested by multiple studies, but frequency unclear in

absence of aerosol-generating procedures in healthcare settings[2]

Virus rarely cultured in respiratory samples > 9 days after symptom onset,

especially in patients with mild disease[5]

Multiple studies describe a correlation between reduced infectivity with decreases

in viral loads and rises in neutralizing antibodies[5]

ACOG: “Data are reassuring that vertical transmission appears to be uncommon”[6]

1. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html 2. WHO. Scientific Brief. July 9, 2020.

3. Wölfel. Nature. 2020;581:465. 4. Zou. NEJM. 2020;382:1177.

5. WHO. Scientific Brief. June 17, 2020. 6. ACOG. Practice Advisory: Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Last updated July 1, 2020. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Updated

Updated](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-9-320.jpg)

![Timing of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission

Based on Symptoms

Prospective study of lab-confirmed

COVID-19 cases (n = 100) and their close

contacts (n = 2761) in Taiwan[1]

‒ Paired index-secondary cases (n = 22)

occurred more frequently with exposure

just before or within 5 days of symptom

onset vs later

Pre-symptomatic infections

‒ Accounted for 6.4% of locally acquired

infections in a study in Singapore (N =

157)[2]

‒ Modelling study of transmission in China

(n = 154) estimated that 44% of

transmissions may have occurred just

before symptoms appeared[3]

A recent systematic review and meta-

analysis estimated that the proportion of

total infections that are truly

asymptomatic range from 6% to 41%

(pooled estimate of 15%)[4]

‒ Asymptomatic transmission rates ranged

from 0% to 2.2% vs symptomatic

transmission rates of 0.8% to 15.4%

‒ 3 studies reported that the cycle

threshold from RT-PCR assays did not

differ between symptomatic and

asymptomatic individuals

1. Cheng. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;[Epub]. 2. Wei. MMWR. 2020;69:411.

3. He. Nature Medicine. 2020;26:672. 4. Byambasuren. MedRxiv. 2020;[Preprint]. Note: this study has not been peer reviewed. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![Nonpharmacologic Preventative Interventions

Inactivation of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV,

and other endemic human

coronaviruses readily accomplished

with 62% to 71% ethanol, 0.5%

hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1% sodium

hypochlorite (in 1 min)[5]

‒ 0.05% to 0.2% benzalkonium

chloride, 0.02% chlorhexidine

digluconate less effective

1. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html 2. WHO. Scientific Brief. July 9, 2020.

3. Leung. Nat Med. 2020;26:676. 4. Chu. Lancet. 2020;395:1973. 5. Kampf. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:246. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Recommended Prevention Strategies[1,2]

Identify and quickly test suspect cases with

subsequent isolation of infected individuals

Quarantine close contacts of infected individuals

Wash hands often with soap and water

Maintain social distance (~ 6 feet)

Wear cloth face cover in public[3,4]

Practice respiratory etiquette

Disinfect frequent-touch surfaces regularly

Avoid crowds, close-contact settings, and poorly

ventilated spaces](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-13-320.jpg)

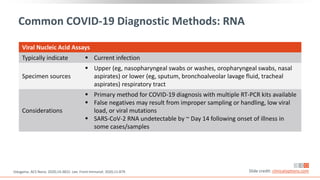

![CDC: Testing Recommendations for SARS-CoV-2

“Viral [nucleic acid or antigen] tests are recommended to diagnose acute

infection.”

Overview of Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Updated August 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-

ncov/hcp/testing-overview.html Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Considerations for Who Should Get Tested

Persons with COVID-19 symptoms: test or self-isolate for ≥ 10 days after symptom onset and ≥ 24 hrs after

symptom resolution

Close contacts (within 6 ft) of known case for ≥ 15 mins: test if vulnerable individual or recommended by state

or local public health officials

No COVID-19 symptoms and no close contact with known case: no test needed

Persons in high transmission area who attended a gathering of ≥ 10 people without widespread mask wearing

or physical distancing: test if vulnerable individual or recommended by state or local public health officials

Work in a nursing home or long-term care facility: test regularly (frequency depends on incidence rate of area)

Live in or receive care in a nursing home or long-term care facility: test if symptomatic, if an outbreak occurs, or

routinely for persons who leave the facility on a regular basis

Critical infrastructure worker, health care worker, or first responder: may be tested according to employer’s

guidelines

Updated](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-22-320.jpg)

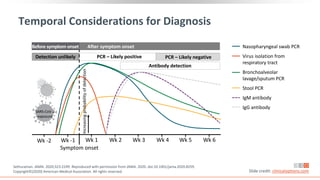

![Temporal Profile of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load

Serial viral loads assessed via

RT-PCR of posterior

oropharyngeal saliva or

endotracheal aspirate* collected

from hospitalized patients in

Hong Kong with laboratory

confirmed COVID-19 (N = 23)[1]

Viral loads highest during first

wk following symptom onset[1]

Pneumonia may develop late

and when URT PCR is negative[2]

*Intubated patients.

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Mean

Viral

Load,

log

10

copies/mL

(SD)

Days After Symptom Onset

Temporal Viral Load in Patients With COVID-19[1]

10

8

6

4

2

0

0 10 20 30

Saliva

Endotracheal aspirate*

Day

Saliva

Endotracheal

0

1

0

1

1

0

2

3

0

3

3

0

4

5

0

5

5

0

6

5

0

7

4

0

8

7

1

9

10

0

10

5

1

11

8

2

12

7

2

13

7

2

14

6

2

15

7

2

16

8

2

17

5

2

18

6

2

19

5

2

20

6

2

21

6

1

22

5

1

23

6

1

24

4

1

25

3

1

26

3

0

27

2

0

28

2

0

29

1

0

1. To. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565. 2. Ai. Radiology. 2020;296:E32.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-24-320.jpg)

![P = .02

P < .001 P < .001

P < .001

Figure 3. A, Viral load of different tissue samples. B, Analysis of viral load in different clinical stages of ...

Viral load assessed via digital droplet PCR of samples collected from patients in

Beijing with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 (N = 76)

Viral Load Varies by Sample Type and Disease Stage

*Early stage: multifocal bilateral or isolated round ground-glass opacity with or without patchy consolidations and prominent peripherally

subpleural distribution on chest CT. Progressive stage: Increasing number, range, or density of lung lesions on chest CT. †Recovery phase:

lesions gradually absorbed. ‡Clinical cure: temperature recovery for > 3 days, improvement in respiratory symptoms, absorption of lung lesions,

and 2 consecutive negative RT-PCR results from respiratory samples tested at least 1 day apart.

Early and progressive stages*

(n = 15)

Recovery stage† (n = 49)

Clinical cure‡ (n = 5)

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Mean

Viral

Load

(copies/test)

Mean

Viral

Load

(copies/test)

Type of Specimens

106

Nasal swabs

Throat swabs

Sputum

Blood

Urine

104

102

100

P < .001

Clinical Disease Stage

106

104

102

100

P < .001

Sputum Viral Load By Disease Stage

Viral Load By Sample Type

Yu. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;[Epub].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-25-320.jpg)

![Chest CT Abnormalities

Most common hallmark features on chest CT images include bilateral peripheral ground-

glass opacities and consolidations of the lungs with peak lung involvement between 6 days

and 11 days post-symptom onset[1-3]

In a study in Wuhan, China, chest CT imaging demonstrated a sensitivity of 97% and

specificity of 25% with RT-PCR as the reference (N = 1014)[4]

‒ 60% to 93% of patients had initial positive lung CT consistent with COVID-19 before the initial

positive RT-PCR result

1. Bernheim. Radiology. 2020;295:685. 2. Pan. Radiology. 2020;295:715. 3. Wang. Radiology. 2020;296:E55. 4. Ai. Radiology. 2020;296:E32. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

29-Yr-Old Man Presenting With Fever for 6 Days[4]

Ground-glass

opacities

Day 6 Day 9 Day 11 Day 17 Day 23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-27-320.jpg)

![SARS-CoV-2 in Stool

Reports of negative pharyngeal and sputum viral tests but fecal samples

testing positive for SARS-CoV-2[1]

Similar viral load but significantly longer duration of viral detection in stool

vs respiratory samples[2]

1. Chen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:790. 2. Zheng. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

10

8

6

4

2

0

Respiratory Stool Serum

Viral

Load

(log

10

copies/mL)

P = .04 P < .001

P < .001

40

50

30

20

10

0

Respiratory Stool Serum

Days

After

Symptom

Onset

P = .02 P < .001

P = .07

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-28-320.jpg)

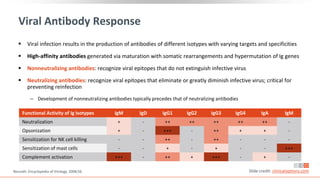

![Neutralizing Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2

Plasma collected from recovered

patients with COVID-19 who had

mild symptoms (N = 175)

Neutralizing antibody titers* varied

Neutralizing and spike-binding

antibodies emerged concurrently

between 10-15 days following

disease onset

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Wu. medRxiv. 2020;[Preprint]. Note: This study has not been peer reviewed.

SARS-CoV-2

NAb

Titers

(ID50)

Disease Duration (Days)

*Assessed via pseudotyped, lentiviral vector-based assay.

NAb Titers Value (N = 175)

Titer range, ID50 < 40 to 21,567

Patients with undetectable level, % 6

Patients with detectable level, %

ID50: < 500 (very low)

ID50: 500-999 (medium low)

ID50: 1000-2500 (medium high)

ID50: > 2500 (high)

30

17

39

14

4096

2048

1024

512

256

128

64

32

16

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 161820 2224

Patient 1

Patient 2

Patient 3

Patient 4

Patient 5

Patient 6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-32-320.jpg)

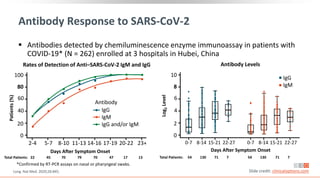

![SARS-CoV-2 Serology for Diagnosis:

Current Recommendations

CDC: Given that it can take 1-3 wks to develop antibodies following infection, antibody test

results should not be used to diagnose someone with an active SARS-CoV-2 infection[1,2]

Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia[3]:

‒ “Molecular testing on a single throat with deep nasal swab is the current test of choice for the

diagnosis of acute COVID-19 infection”

‒ “COVID-19 IgG/IgM rapid tests have no role to play in the acute diagnosis of COVID-19 virus

infection . . . ”

‒ “COVID-19 IgG/IgM rapid tests will miss patients in early stages of disease when they are

infectious to other people”

WHO: “At present, based on current evidence, WHO recommends the use of these new

point-of-care immunodiagnostic tests only in research settings”[4]

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-professional.html.

2. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/serology-overview.html.

3. https://www.rcpa.edu.au/getattachment/bf9c7996-6467-44e6-81f2-e2e0cd71a4c7/COVID19-IgG-IgM-RAPID-POCT-TESTS.aspx.

4. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/advice-on-the-use-of-point-of-care-immunodiagnostic-tests-for-covid-19.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-33-320.jpg)

![COVID-19 Incubation: Infection to Illness Onset

Among 10 confirmed NCIP cases in

Wuhan, Hubei province, China[1]

‒ Mean incubation: 5.2 days

(95% CI: 4.1-7.0)

Among 181 confirmed SARS-CoV-2

infections occurring outside of Hubei

province[2]

‒ Median incubation: 5.1 days

(95% CI: 4.5-5.8)

‒ Symptom onset by Day 11.5 of

infection in 97.5% of persons

1. Li. NEJM. 2020;382:1199. 2. Lauer. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Estimated Incubation Period Distribution[1]

0.25

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0

Relative

Frequency

Days From Infection to Symptom Onset

21

0 7 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-35-320.jpg)

![COVID-19 Clinical Presentation May Vary by Age, Sex

Observational study of Europeans with mild-to-moderate

COVID-19 (ie, no ICU admission) via standardized

questionnaire during March 22-April 10, 2020 (N = 1420)[1]

‒ Mean duration of symptoms (n = 264): 11.5 ± 5.7 days

‒ Ear, nose, throat complaints more common in young patients;

fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, diarrhea in elderly patients

(P < .01)

‒ Loss of smell, headache, nasal obstruction, throat pain, fatigue

more common in women; cough, fever in men (P < .001)

Among 17 fatal COVID-19 cases detailed by the China

National Health Commission, median time from first

symptom to death: 14 days (range: 6-41)[2]

‒ Numerically faster in older patients: 11.5 days if ≥ 70 yrs vs 20

days if < 70 yrs (P = .033)

1. Lechien. J Intern Med. 2020;[Epub]. 2. Wang. J Med Virol. 2020;92:441. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Symptom,[1] % N = 1420

Headache 70.3

Loss of smell 70.2

Nasal obstruction 67.8

Asthenia 63.3

Cough 63.2

Myalgia 62.5

Rhinorrhea 60.1

Taste dysfunction 54.2

Sore throat 52.9

Fever (> 38°C) 45.4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-37-320.jpg)

![Vaccine Development Pathway

Traditional vaccine development pathway[1]

‒ Target discovery/validation, preclinical stage, manufacturing development, clinical

assay optimization: 3-8 yrs

‒ Phase I (safety), phase II (safety/immunogenicity), phase III (safety/efficacy) clinical

trials: 2-10 yrs

‒ Regulatory review: 1-2 yrs

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. Heaton. NEJM. 2020;[Epub].

2. The New York Times. Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html

SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidates in Development[2]

Preclinical Phase I Phase II Phase III Approval

Vaccines not

yet in human trials

Vaccines testing

safety and dosage

Vaccines in expanded

safety trials

Vaccines in large-

scale efficacy

tests

Vaccine approved

for limited use

140+ 19 12 5 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-44-320.jpg)

![Virus genes

(some inactive)

Vaccine Candidates in Development for SARS-Cov-2

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Funk. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2020;[Epub].

Vaccine Platforms Vaccine Candidates

44

16

14

10 12

20

3

8

Other DNA

RNA

SARS-CoV-2

inactivated

SARS-CoV-2

live

attenuated

Viral vector

(nonreplicating)

Viral vector

(replicating)

Protein based

Viral vector

(nonreplicating)

Viral vector

(replicating)

Virus

(inactivated)

Virus

(attenuated)

DNA

RNA (+ LNPs)

Protein based

(eg, spike)

Coronavirus

spike gene

Virus genes

(some inactive)

Coronavirus

spike gene](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-45-320.jpg)

![mRNA Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2:

Preliminary Safety Report

No serious adverse events reported

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Jackson. NEJM. 2020;[Epub].

0

Symptom Dose Group Vaccination 1 Vaccination 2

Mild Moderate Severe

Any systemic

symptom

Arthralgia

Fatigue

Fever

Chills

Headache

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

Participants (%)

0

Symptom Dose Group Vaccination 1 Vaccination 2

Myalgia

Nausea

Any local

symptom

Size of erythema

or redness

Size of induration

or swelling

Pain

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

25 μg

100 μg

250 μg

Participants (%)

100

40 60 80

20 100

40 60 80

20 100

40 60 80

20

100

40 60 80

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-46-320.jpg)

![Dose and Age Considerations

Many phase III vaccine studies fail because the dose chosen did not

best balance safety and efficacy[1]

Immune function declines with age and this decline is likely partially

responsible for the greater risk of severe COVID-19 in older adults

may lead to poor vaccine responses and the need for higher vaccine

doses in older adults[2,3]

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. Musuamba. CPT Pharmacometrix Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6:418. 2. Heaton. NEJM. 2020;[Epub]. 3. Zhu. Lancet. 2020;[Epub].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-47-320.jpg)

![Medical Management of Mild COVID-19

1. WHO Interim Guidance. Clinical management of COVID-19. May 27, 2020.

2. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Management of persons with COVID-19. Last updated June 11, 2020.

3. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with COVID-19. Last updated May 12, 2020. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

WHO[1]

Isolate suspected/confirmed cases to contain

SARS-CoV-2 transmission; isolation can occur

at home, in a designated COVID-19 health or

community facility

Treat symptoms (eg, antipyretics for fever,

adequate nutrition, appropriate rehydration)

Educate patients on signs/symptoms of

complications that, if developed, should

prompt pursuit of urgent care

NIH[2,3]

Majority of cases managed in ambulatory

setting or at home (eg, by telemedicine)

Close monitoring advised for symptomatic

patients with risk factors for severe disease;

rapid progression possible

No specific lab tests indicated if otherwise

healthy

In non-hospitalized patients, do not initiate

anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapy to

prevent VTE or arterial thrombosis unless

other indications exist](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-49-320.jpg)

![Management[1]

Monitor closely, as pulmonary disease can

rapidly progress

Administer empiric antibiotics if bacterial

pneumonia/sepsis strongly suspected; re-

evaluate daily and de-escalate/stop treatment

if no evidence of infection

Use hospital infection prevention and control

measures; limit number of

individuals/providers entering patient room

Use AIIRs for aerosol-generating procedures;

staff should wear N95 respirators or PAPRs vs

surgical masks

Medical Management of Moderate COVID-19

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Initial Evaluation[1]

May include chest x-ray, ultrasound, or CT

Perform ECG if indicated

Obtain CBC with differential and metabolic

profile including liver/renal function

Inflammatory markers (eg, CRP, D-dimer,

ferritin) may be prognostically valuable

Isolation (Home vs Healthcare Facility)[2]

Dependent on clinical presentation,

requirement for supportive care, presence of

vulnerable household contacts; if high risk of

deterioration, hospitalization preferred

1. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Management of persons with COVID-19. Last updated June 11, 2020.

2. WHO Interim Guidance. Clinical management of COVID-19. May 27, 2020.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-50-320.jpg)

![Acute Coinfection Treatment[1]

Administer empiric antimicrobials within 1 hr of

initial assessment based on clinical judgment,

patient host factors, and local epidemiology;

knowledge of blood cultures before antimicrobial

administration ideal

Assess daily for antimicrobial de-escalation

Severe Pneumonia Treatment[1]

Equip patient care areas with pulse oximeters,

functioning oxygen systems, and disposable, single-

use, oxygen-delivering interfaces

Provide immediate supplemental oxygen to

patients with emergency signs (eg,

obstructed/absent breathing, severe respiratory

distress, central cyanosis, shock, coma, or

convulsions) and anyone with SpO2 < 90%

Monitor for clinical deterioration (eg, rapidly

progressive respiratory failure, shock); provide

immediate supportive care

Practice cautious fluid management in patients

without tissue hypoperfusion and fluid

responsiveness

Medical Management of Severe COVID-19

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. WHO Interim Guidance. Clinical management of COVID-19. May 27, 2020.

2. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Management of persons with COVID-19. Last updated June 11, 2020.

Evaluation[2]

Perform evaluations outlined for moderate disease](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-51-320.jpg)

![≥ 24 hrs since resolution

of fever, last antipyretics

CDC: Discontinuation of Transmission-Based

Precautions in Symptomatic COVID-19 Patients

“A test-based strategy is no

longer recommended [except

for rare situations] because, in

the majority of cases, it results

in prolonged isolation of

patients who continue to shed

detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA but

are no longer infectious.”

Symptom-Based Strategy

And

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/disposition-hospitalized-patients.html Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

Improvement in symptoms

(eg, cough, shortness of breath)

And

≥ 10 days since symptom onset

for mild to moderate illness,

≥ 20 days for severe to critical illness

or those severely immunocompromised](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-55-320.jpg)

![Burden of Thrombosis in Patients With COVID-19

Study Country Design Population N Thromboprophylaxis Screening VTE Rate, %

China[1] Retrospective ICU 81 No No 25.0

France[2] Prospective ICU 150 Yes No 11.7*

France[3] Retrospective ICU 26 Yes Yes 69.0

France[4] Retrospective ICU 107 Yes No 20.6†

The

Netherlands[5] Retrospective ICU 184 Yes No 27.0

Italy[6] Retrospective Inpatient 388 Yes No 21.0

United

Kingdom[7] Retrospective ICU 63 Yes No 27.0

*Pulmonary embolisms in COVID-19 ARDS vs 2.1% in matched non-COVID-19 ARDS.†Pulmonary embolism vs 6.1% in non–COVID-19 ICU patients.

1. Cui. J Throm Maemost. 2020;[Epub]. 2. Helms. Intesive Care Med. 2020;46:1089. 3. Llitjos. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1743. 4. Poissy.

Circulation. 2020;142:184. 5. Klok. Throm Res. 2020;191:145. 6. Lodigiani. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9. 7. Thomas. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

New](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-56-320.jpg)

![Autopsy Evidence of Lung Damage in COVID-19

Prospective study to compare

clinical findings with data from

autopsy (N = 12)[1]

‒ 7/12 patients had unsuspected

bilateral DVT

‒ 4/7 died from PE

Alveolar Damage[2]

Organizing Microthrombus[2]

1. Wichmann. Ann Int Med. 2020;[Epub]. 2. Carsana. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30434-5. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

New](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-57-320.jpg)

![Guidance on Thromboprophylaxis

NIH[1] ASH[2]

Hospitalized adults with COVID-19 should receive VTE

prophylaxis per the SoC for other hospitalized adults

Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy should not be

used to prevent arterial thrombosis outside of the usual

SoC for patients without COVID-19

Currently insufficient data to recommend for or against

the use of thrombolytics or increasing anticoagulant

doses for VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized COVID-19

patients outside of clinical trial

Hospitalized patients should not be routinely discharged

on VTE prophylaxis (extended VTE prophylaxis can be

considered in patients with low bleeding risk and high

VTE risk)

All hospitalized adults with COVID-19 should receive

thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight

heparin over unfractionated heparin, unless bleeding

risk outweighs thrombosis risk

Fondaparinux is recommended in the setting of

heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

In patients in whom anticoagulants are contraindicated

or unavailable, use mechanical thromboprophylaxis

(eg, pneumatic compression devices)

Encourage participation on clinical trials rather than

empiric use of therapeutic-dose heparin in COVID-19

patients with no other indication for therapeutic dose

anticoagulation

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. NIH. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Updated: May 12, 2020. 2. American Society of Hematology. COVID-19 and VTE/

Anticoagulation: Frequently Asked Questions. 3. Spyropoulos. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;[Epub]. 4. Moores. CHEST. 2020;[Epub].

*Additional recommendations available from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis[3], and CHEST.[4]

Recommending Organization*

New](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-59-320.jpg)

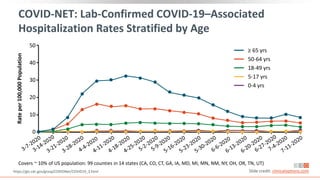

![COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization and

Death Rates Increase With Age in US

1. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covid-net/purpose-methods.html.

2. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html#demographics. Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

*Lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases; covers ~ 10% of US population: 99 counties in 14 states (CA, CO, CT, GA, IA, MD, MI, MN, NM, NY, OH, OR, TN, UT).

†Data from 109,622 deaths in confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases as reported by US states and territories; age group data available for 109,602

deaths (99%).

COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations*[1] COVID-19–Associated Deaths†[2]

%

of

Total

Deaths

Age Group (Yrs)

Rates

per

100,000

Population

Wk

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

0-4 yrs

5-17 yrs

18-49 yrs

50-64 yrs

65+ yrs

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

0-4: < 0.1%

5-17: < 0.1%

18-29: 0.5%

30-39: 1.3%

40-49: 3.1%

50-64: 15.4%

65-74: 20.9%

75-84: 26.4%

85+: 32.4%

New](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![Key RCT Data For Other Investigational Agents

Agent N Population Comparator Primary Outcome

Lopinavir/ritonavir[1] 199 Adults, severe SOC alone No difference in time to clinical improvement

Lopinavir/ritonavir[2] 86

Adults, mild-to-

moderate

Umifenovir or

no antiviral

No difference in rate of positive-to-negative

conversion of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid

Lopinavir/ritonavir +

ribavirin + IFNβ1b[3] 86 Adults, hospitalized LPV/RTV

Significantly shorter median time from start

of study treatment to negative

nasopharyngeal swab for combination

treatment

Lopinavir/ritonavir*[4] 1596 Hospitalized SOC alone No difference in 28-day mortality

Favipiravir*[5] 240 Adults, pneumonia Umifenovir No difference in clinical recovery rate of Day 7

Hydroxychloroquine*[6] 150

Adults, mild-to-

moderate

SOC alone

No difference in negative conversion of SARS-

CoV-2 by Day 28

Hydroxychloroquine*[7] 1542 Hospitalized SOC alone No difference in 28-day mortality

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. Cao. NEJM. 2020;382:1787. 2. Li. Med. 2020;[Epub]. 3. Hung. Lancet. 2020;395:1695.

4. https://www.recoverytrial.net/files/lopinavir-ritonavir-recovery-statement-29062020_final.pdf

5. Chen. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.17.20037432 6. Tang. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.10.20060558

7. https://www.recoverytrial.net/files/hcq-recovery-statement-050620-final-002.pdf

*Published as a preprint or by press release only; not yet peer-reviewed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-67-320.jpg)

![Key RCT Data For Other Investigational Agents (Cont.)

Agent N Population Comparator Primary Outcome

Tocilizumab[1,2] 129

Moderate or

severe

pneumonia

Standard care

alone

Improvement in composite

endpoint of death or need for

ventilation at Day 14 with

tocilizumab vs standard care

Sarilumab

(200 or 400 mg)[3,4] 457 Severe or critical Placebo

CRP decline: 77% and 79% vs 21%

IDMC recommended continuing

phase III only in critical subgroup

with 400 mg sarilumab vs placebo

Slide credit: clinicaloptions.com

1. https://www.aphp.fr/contenu/tocilizumab-improves-significantly-clinical-outcomes-patients-moderate-or-severe-covid-19

2. NCT04331808. 3. NCT04315298. 4. https://newsroom.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regeneron-and-

sanofi-provide-update-us-phase-23-adaptive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covid-19-230320060249-76fed1bc/85/Covid-19-pdf-68-320.jpg)