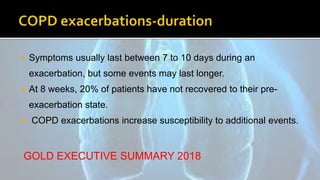

This document discusses the management of COPD exacerbations. It begins by defining a COPD exacerbation and classifying exacerbations by severity. It then outlines the goals of exacerbation treatment and recommends short-acting bronchodilators as the initial treatment. It advocates for systemic corticosteroids to improve outcomes and antibiotics when indicated. The document also recommends non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Finally, it stresses implementing prevention strategies after an exacerbation.