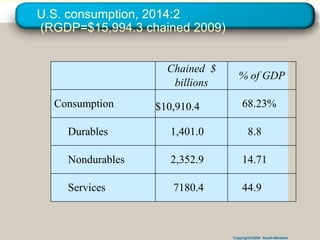

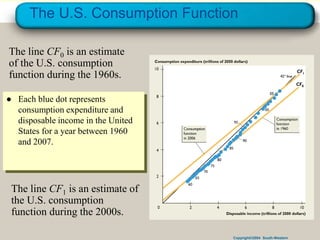

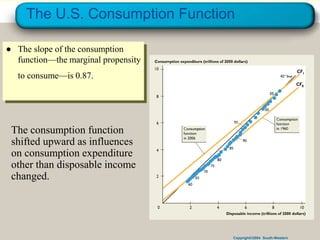

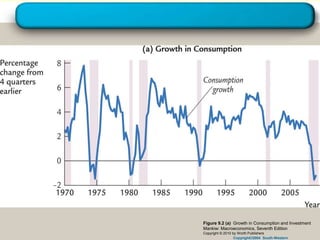

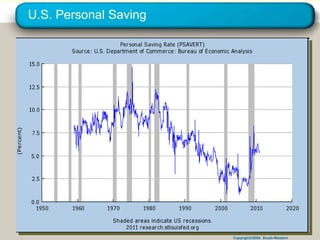

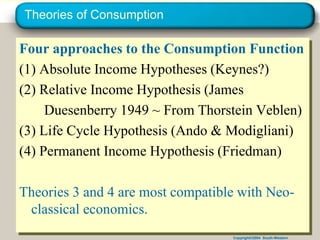

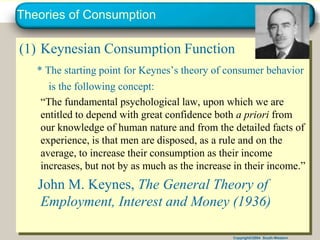

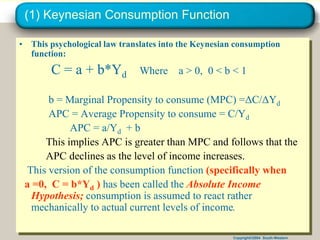

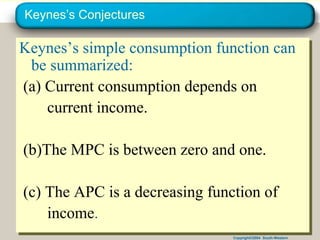

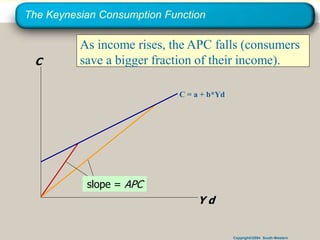

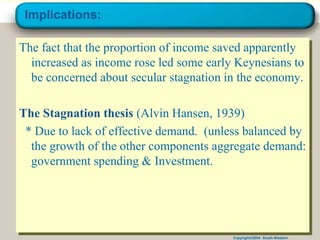

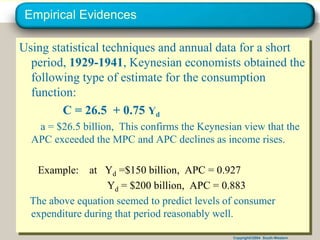

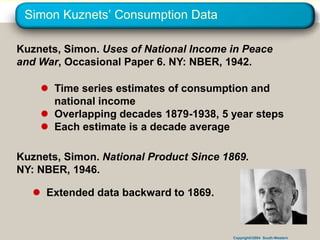

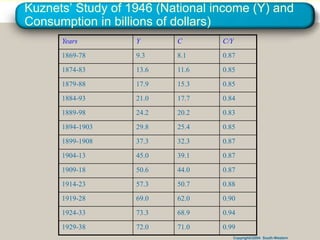

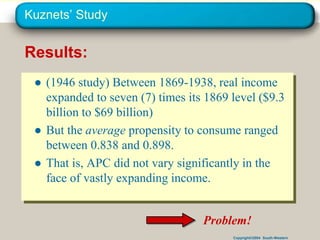

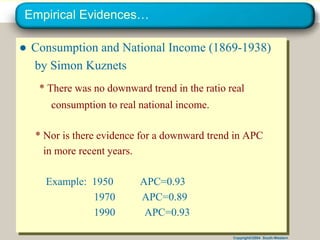

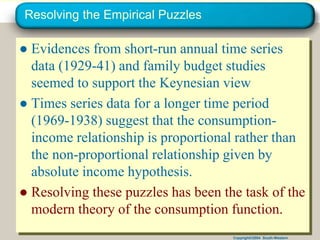

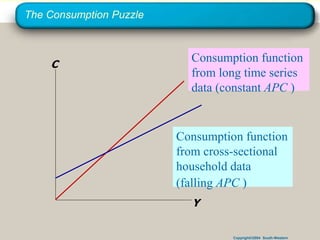

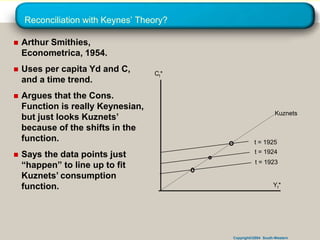

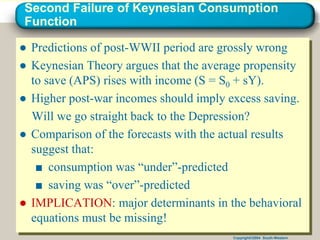

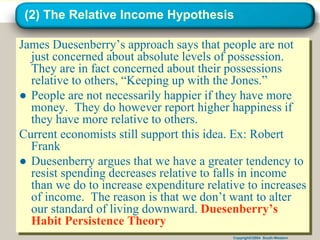

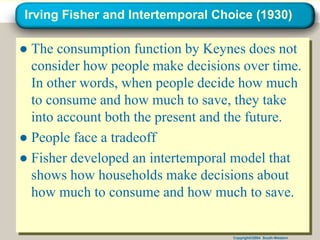

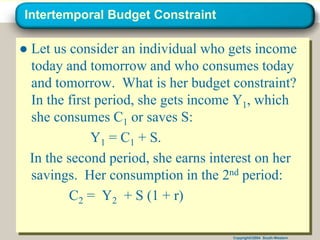

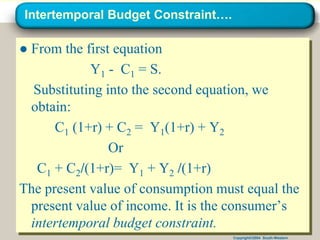

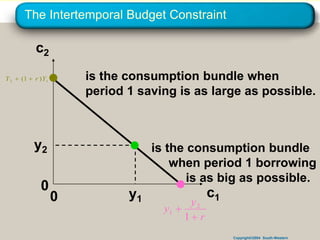

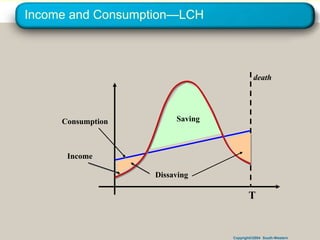

This document summarizes theories of consumption, including Keynes' absolute income hypothesis and the puzzles it posed for empirical data. It discusses alternatives like Duesenberry's relative income hypothesis and Fisher's intertemporal choice theory. It also reviews studies by Kuznets, Smithies, and others analyzing consumption-income data and attempts to reconcile findings with Keynesian theory.