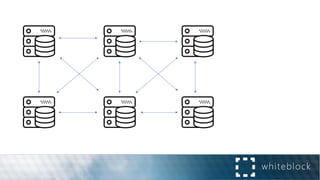

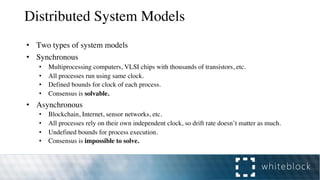

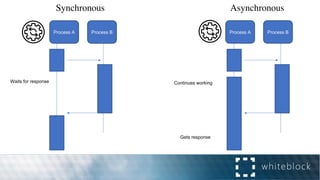

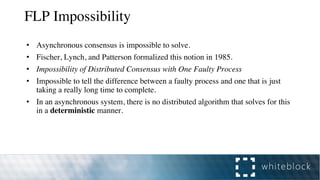

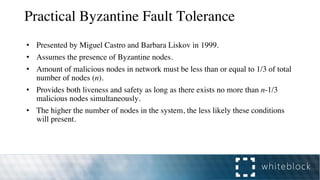

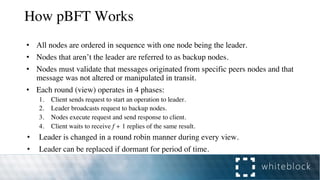

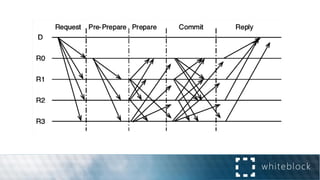

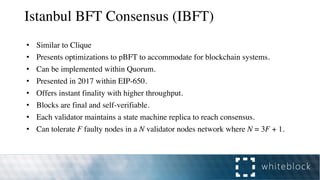

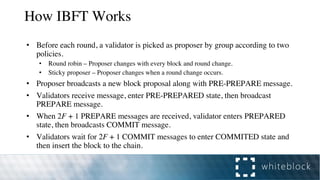

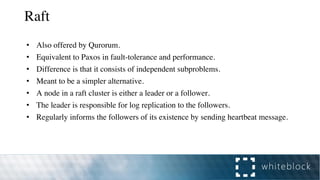

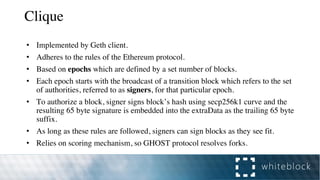

The document provides a comprehensive overview of consensus algorithms used in distributed systems, detailing their necessity for enabling agreement among independent nodes despite potential faults. It covers various models, including synchronous and asynchronous systems, and explains key algorithms such as Paxos, Byzantine Fault Tolerance, and Proof of Work, along with their application in blockchain networks. Additionally, it highlights specific implementations like Raft and Proof of Authority within permissioned and public networks, discussing their scalability, efficiency, and security considerations.