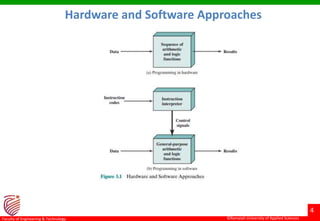

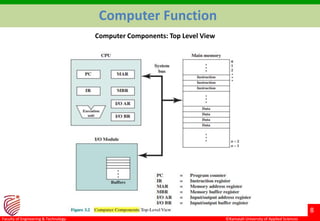

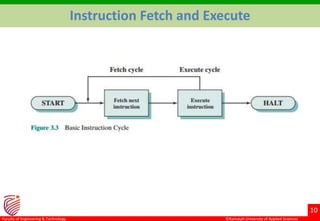

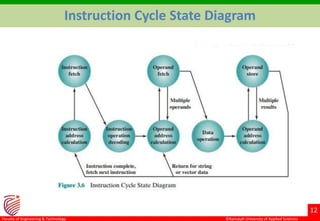

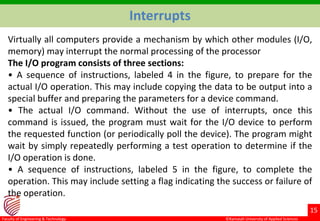

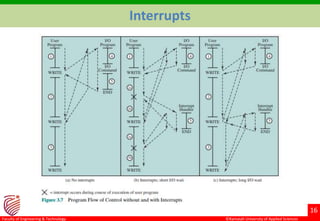

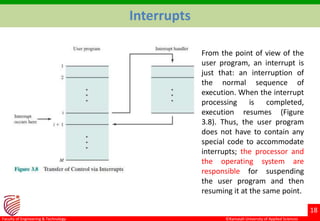

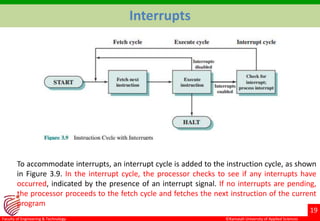

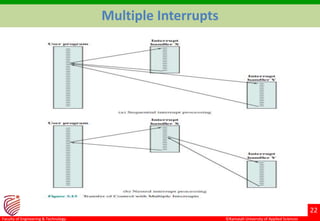

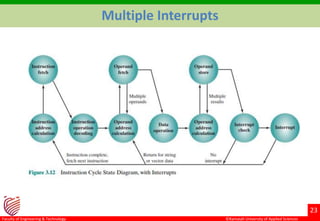

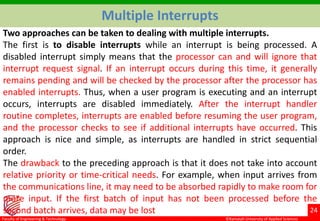

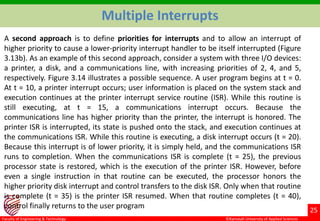

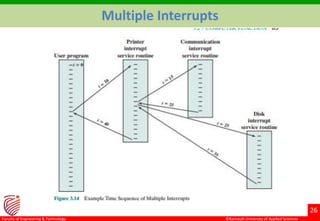

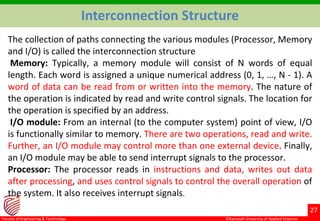

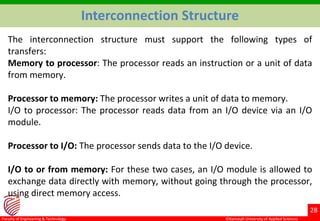

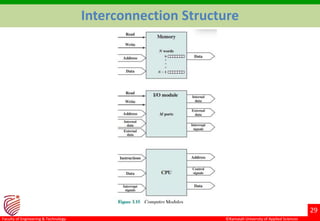

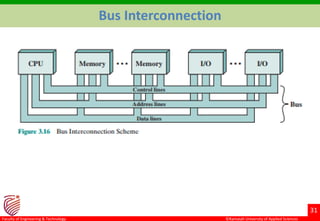

The document discusses the fundamental concepts of computer architecture based on the von Neumann model, which includes the storage of data and instructions in a single memory and the sequential execution of instructions. It describes the structure and functions of the CPU, memory, input/output (I/O) components, and the interconnection structure among these elements, highlighting the roles of interrupts in managing concurrent operations and data transfers. Additionally, it explains the bus interconnection system facilitating communication between various computer modules using control, data, and address lines.