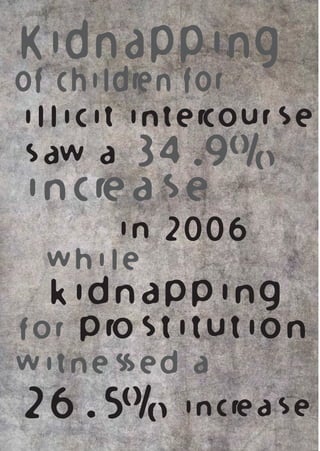

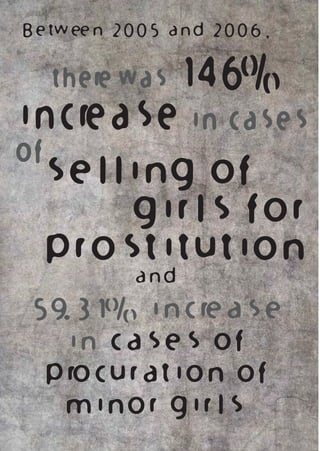

The document is a handbook aimed at combating child trafficking, highlighting its prevalence and legal frameworks. It underscores the need for specialized legal definitions and protective measures for trafficked children, emphasizing the roles of various stakeholders in addressing this organized crime. The handbook provides guidance on interventions, legal procedures, and victim protection, drawing on both national and international laws.

![26

Information for Citizens

If for some reason reporting to the police seems difficult, Child Line or the nearest NGO in the area/city

working in this field should be contacted.

Child Line is a helpline for children in difficult circumstances. For Child Line we can dial 1098 from

anywhere in the country.

Once the matter is before the authorities, the child may need support in filing the complaint and

throughout the legal process. We may choose to opt out of it. But as responsible citizens we must then

ensure the involvement of Child Line or the nearest NGO or a crisis intervention centre that can provide

such support to the victim child.

Giving shelter to a distressed child is indeed a good deed. But laws relating to care and protection of

children in difficult circumstances clearly require that a child may only be kept by ‘a fit person’, or in a

“fit institution” recognised so by the juvenile justice legislation.

What is a ‘fit person’ / ‘fit institution’

Under the Juvenile Justice Act as amended in 2006

“fit institution” means a government or a registered non-governmental organization or a voluntary

organization prepared to own the responsibility of a child and found fit by the State Government on

the recommandation of the competent authority [Section 2 (h)]

“fit person” means a person, being a social worker or any other person who is prepared to own the

responsibility of a child and is found fit by the competent authority to receive and take care of the

child [Section 2 (i)]

Only a competent authority (CWC in this case) or the State Government on the recommendation

of a competent authority can declare a person or an institution ‘fit’ under the juvenile justice law.

In most States it is the Department ofWomen & Child Development that acts as the competent

authority. However, in a Federal Republic like India, the States may follow different nomenclatures

for the department responsible for child protection, justice and welfare. Some States may include

juvenile justice under social welfare, while some others may see it as part of child welfare and hence

a subject of the Department ofWomen and Child Development.

Requirements for NGOs

NGOs receiving information of child trafficking may take action or may choose to refer the matter to any

other appropriate agency dealing with such issues, including Child Line. It is not necessary for all NGOs

to directly intervene and act on such cases, especially if the issue does not fall within the mandate of the

organisation and there is no expertise to handle such cases.

An NGO and/or ‘a fit institution’ under the juvenile justice legislation working on child protection

issues may choose to investigate into an incident of child trafficking in order to confirm the facts before

reporting the matter to the police or before carrying out a rescue operation. It must be remembered

that carrying out a preliminary enquiry can alert the traffickers. Also, the decision to carry out some

preliminary enquiry must be guided by the urgency of the situation as a delay may cause harm to the

child.

A good practice is that of working with the official structures rather than acting as a parallel structure for

law enforcement and social security. Lets not forget that an NGO or persons employed in an NGO have

no more rights than any other ordinary citizen has in a legal action.

It is important to always seek police assistance in any rescue operation. To reiterate, once a child is

rescued, all ‘fit persons’/ ‘fit institutions’ including the Police, the Child Line, NGOs, social workers and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combat-child-trafficking-151014101424-lva1-app6892/85/Combating-Child-Trafficking-A-User-s-Handbook-32-320.jpg)

![34

What is a FIR?

The first information received by the police of the commission of a cognizable offence becomes the First

Information Report. It is the basis for further investigation by the Police. According to Section 154 of the

Criminal Procedure Code (Cr.P.C.) a criminal complaint made to the police is reduced in writing and

recorded by the officer in charge of a police station [station house officer (SHO)]. This section stipulates that

whenever a citizen informs the police, or the police learn about the occurrence of a cognizable crime the

SHO shall institute a First Information Report [FIR], which initiates the criminal investigation.1

A FIR is lodged only in cognizable offences. It is the first step for processing the case.

1 Verma Arvind, Reporting a Crime, January 2004, http://www.indiatogether.org/2004/jan/gov-policefir.htm

Sec. 154 of the CrPC: Information in cognizable cases

(1) Every information relating to the commission of a cognizable if given orally to an officer in charge

of a police station, shall be reduced to writing by him or under his direction, and be read over to the

informant; and every such information, whether given in writing or reduced to writing as aforesaid, shall

be signed by the person giving it, and the substance thereof shall be entered in a book to be kept by such

officer in such form as the State Government may prescribe in this behalf.

(2) A copy of the information as recorded under sub-section (1) shall be given free of cost to the

informant.

(3) Any person aggrieved by a refusal on the part of an officer in charge of a police station to record the

information referred to in sub-section (1) may send the substance of such information, in writing and

by post, to the Superintendent of Police concerned who, if satisfied that such information discloses the

commission of a cognizable offence, shall either investigate the case himself or direct an investigation to

be made by any police officer subordinate to him, in the manner provided by this code and such officer

shall have all the powers of an officer of a police station in relation to that offence.

Daily Diary is basically a diary of daily proceedings in the police station.The officer-in-charge records all

the cases brought before its notice in the diary and each case is given a registration number for future

reference.

The police officer on duty is required to mention the brief facts about the case in the daily diary entry,

including for instance, the name of the assailant, names of the witnesses and the weapon used.

There could be a host of daily registers within a police station as per the categories of crimes viz, IPC

crimes, crimes under other statutory laws, crimes under certain local and special laws.Within the IPC

crimes, there could be separate diaries and entries for more prevalent forms of crimes viz, kidnapping,

hurt, rape, murder etc.

Relationship between a Complaint made to the Police and FIR

By itself, a complaint made to the police is not enough as a documentary proof of a charge of an offence,

as there is no reference to cognizable charges in it.

Therefore, a complaint involving a cognizable and bailable or non-bailable offence must be converted

into a FIR.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combat-child-trafficking-151014101424-lva1-app6892/85/Combating-Child-Trafficking-A-User-s-Handbook-40-320.jpg)

![52

A list of other labour laws that prohibit child labour and/or regulate working conditions for child labourers

and can be used to book the employers is as follows:

The Factories Act, 1948

The Plantation Labour Act, 1951

The Mines Act, 1952

The Merchant Shipping Act, 1958

The Apprentices Act, 1961

The Motor Transport Workers Act, 1961

The Beedi and Cigar Workers (Conditions of Employment) Act, 1966

The W.B. Shops & Establishment Act, 1963

In M.C. Mehta v. State of Tamil Nadu and others10

, the Supreme Court held that the manufacturing process

of matches and fireworks is hazardous and even fatal at times.Therefore, the Court gave following

directions to eradicate child labour in the country: an adult (whose name would be suggested by the

parent guardian of the concerned child) should get a job in lieu of the child, or deposit of a sum of

Rs. 25,000/- in the Child Labour Rehabilitation-cum-Welfare Fund. In case of getting employment for an

adult, the parents/guardian shall have to withdraw his child from the job. Even if no employment would

be provided, the parent / guardian shall have to see that his child is spared form the requirement to do the

job, as an alternative source of income would have become available to him.The employment so given

could as well be the industry where the child is employed, a public undertaking and would be manual in

nature as much as the child in question must be engaged in doing manual work.The understanding chosen

for employment shall be one, which is nearest to the place of residence of the family. The employment

given or payment made would cease to be operative if the child would not be sent by the parent / guardian

for education. On discontinuation of the employment of the child, his education would be assured in

suitable institution with a view to make it a better citizen. Further, in view of the magnitude of the task,

a separate cell in the Labour Department of the appropriate Government would be created. Monitoring

of the scheme would also be necessary and the Secretary of the Department could perhaps do this work.

Over all monitoring by the Ministry of Labour Government of India, would be beneficial and worthwhile.

Insofar as the non-hazardous jobs are concerned, the inspector shall have to see that the working hours

of the child are not more than four to six hours a day and it receives education at least for two hours each

day. It would also be seen that the entire cost of education is borne by the employer.

Trafficking for Begging

Children are trafficked within the country and also across borders for begging. The following legal provisions

can be used to punish those who traffic children or use them for purposes of begging:

Relevant provisions in the IPC

Kidnapping or maiming a minor for begging (Section 363A)

10 [(1991) 1 SCC 283], [(1996) 6 SCC 756]; AIR 1997 SC 699

‘Begging’ is a subject in the Concurrent and the State lists in the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution

of India. Accordingly, ‘anti-beggary’ laws have been put in place in 16 States and 2 UnionTerritories.The

term ‘anti-beggary’ clearly suggests that these laws are about prohibiting begging, declaring it as an

offence and treating all beggars as criminals.They do not contain any provisions to deal with trafficking

of children for begging and the inherent exploitation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combat-child-trafficking-151014101424-lva1-app6892/85/Combating-Child-Trafficking-A-User-s-Handbook-58-320.jpg)