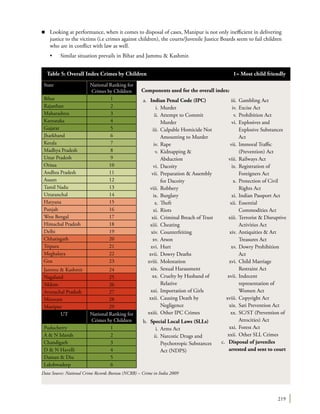

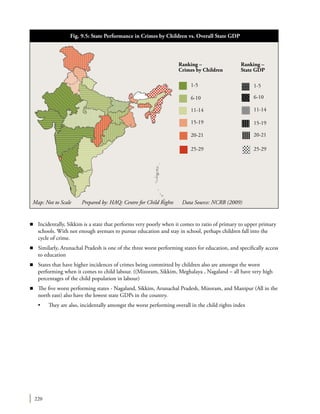

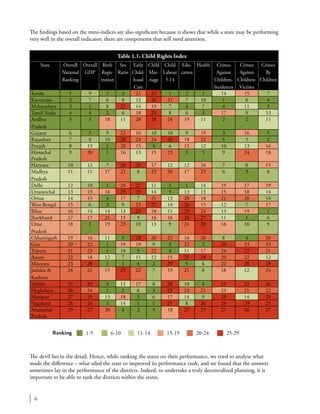

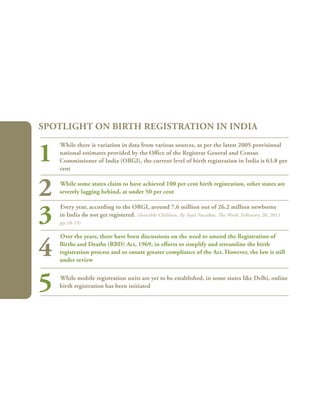

The document presents the India Child Rights Index, developed by Haq: Centre for Child Rights, aimed at assessing and ranking the performance of states and union territories in fulfilling children's rights across various sectors. It highlights the methodology used, including indicators related to birth registration, health, education, and child labor, while emphasizing the need for credible and comprehensive data. The index aims to identify areas requiring attention to promote inclusive development for children in India.

![35

What is even more disconcerting is that because the laws dealing with child

labour are weak – a bailable offence with a minimum of three months

and a maximum of a year’s imprisonment OR/AND a fine of Rs. 10,000

extending to Rs. 20,000 – the implementation of the law remains tardy.

Taking recourse to the choice given, in almost all cases the employers are let

off with a fine.

The Government is yet to implement the CRC Committee’s

recommendation that the 1986 Child Labour Act be amended so that

government schools and training centres are no longer exempt from

prohibitions on employing children; and coverage is expanded to

include agriculture and other informal sectors or that the Factories Act

be amended to cover all factories or workshops employing child labour

and the Beedi Act be amended so that exemptions for household–based

production are eliminated.

CRC Committee’s recommendation to India to withdraw its declaration on Article 32

of the Convention seems to be falling on deaf ears. In fact, in the light of enactment of the law guaranteeing

free and compulsory education to all children aged 6–14 years, the child labour law, policy and schemes are left

with no meaning and should not be required at all. As the current child labour law allows regulation of child

labour in some sectors, it is violative of the fundamental right to education guaranteed under Article 21A of the

Constitution of India.

State Rules under Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act

In 2007 the Ministry of Women and Child Development notified the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection

of Children) Rules, 2007 as the central model rules on juvenile justice. Under Rule 96 of these central model

rules, the states are required to frame their own rules conforming to the 2007 central model rules or else the

central model rules apply mutatis mutandis. The exact status of formulation of juvenile justice rules in the states

Committee recommends withdrawal of declaration on Article 32

The Committee encourages the State party to withdraw its declaration with respect to article 32 of the

Convention, as it is unnecessary in light of the efforts the State party is making to address child labour.

28 January 2000

CRC/C/15/Add.115

In light of the State party’s numerous measures to implement progressively article 32 of the

Convention, the Committee has serious doubt at the necessity of this declaration....In line with

its previous recommendations [Ibid., para. 66], and in light of the 1993 Vienna Declaration and

Programme of Action, the Committee urges the State party to withdraw the declaration made to article

32 of the Convention.

CRC/C/15/Add.228

30 January 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/india-child-rights-index-151015094255-lva1-app6891/85/India-Child-Rights-Index-43-320.jpg)

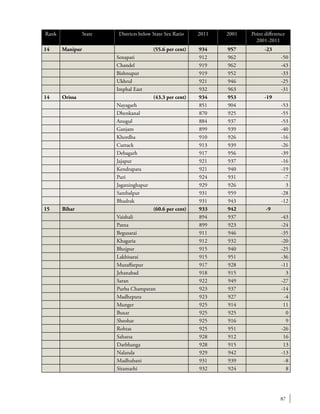

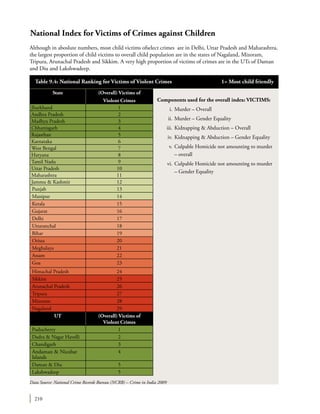

![212

When Protectors Turn Abusers

Our experience at HAQ: Centre for Child Rights

shows us every day that protectors have turned abusers

themselves. Children face violence in families, in schools

and in the institutions set up to give refuge to street

children. Children with disabilities, girl children and

orphans are often exposed as perpetrating violence against

their wards.

Besides incest, some of the most unfortunate

manifestations of

child abuse that one

finds in the country

today are the ones

where children suffer

at the hands their

own protectors. This

includes:

• Female foeticide

and infanticide

• Child marriage

• Domestic

violence

• Custodial rape

• Institutional

Violence

As we know, many of these do not get recorded and enumerated as the perpetrators are invariably those meant

to protect children. Traditionally, the Indian society is a fairly conservative society, where children continue

to be treated as extensions of their parents. Thus, what the parents or caregivers do for them or to them is

often perceived as beyond any questioning. Only in recent times, studies have thrown light on the need

to protect children from abuse even at home, breaking the myth of home as the safest haven. As professor

Savitri Goonesekere states, “the child’s right to family privacy and the focus on parental responsibility in

the Convention [UNCRC] means that in some senses the family is beyond scrutiny. The child’s right to

survival, development, protection and participation are identified with the family’s interest in the child on the

assumption that the family will fulfill its responsibilities to the children. Nevertheless, the Convention’s concept

of ‘protection’ permits state intervention to safeguard a child in circumstances where the family is dysfunctional

or is not fulfilling its responsibilities…This concept of state intervention is the very source of the child’s

protection rights.”8

(Goonesekere. 1998. 252)

Child Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse in the NCRB can be found under rape and

incest, but it is only in the context of girls. The NCRB

unfortunately does not provide data on sexual abuse of

boys. It is frequently assumed that sexual abuse occurs

While all forms of child abuse cut across

caste and class barriers, discrimination on

grounds of gender and caste undoubtedly

rule the crime and abuse roster.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/india-child-rights-index-151015094255-lva1-app6891/85/India-Child-Rights-Index-220-320.jpg)