This document describes the development of a diagnostic scoring system for myxedema coma (MC), a life-threatening complication of severe hypothyroidism. The authors retrospectively analyzed patients with suspected MC and derived clinical criteria to distinguish MC from uncomplicated hypothyroidism or other causes of coma. They assigned weighted points based on alterations in temperature, consciousness, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and metabolic systems. When applied to their patients, a score of ≥60 had 100% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity for diagnosing MC. Validation in literature cases supported discriminating MC from non-MC with this scoring system.

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

1.22.The area under the ROC curve was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.65-1.00), and the score of 60 had

100% sensitivity, and 85.71% specificity.

Conclusions: The scoring system proposed indicates a score of ≥ 60 potentially diagnosing

MC, whereas scores between 45-59 could classify patients at risk for MC.

Abbreviations:

MC = myxedema coma; ROC = receiver operating characteristic; TSH = thyroid stimulating

hormone; T4 = thyroxine; T3 = triiodothyronine; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale

APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA = Sequential Organ

Failure Assessment; SD = standard deviation; MWHC = Medstar Washington Hospital

Center; VAMC = Veterans Affair Medical Center.

Introduction

Myxedema coma is a rare form of extreme hypothyroidism with a mortality rate that may

approach 60% [1]. The condition represents a state of decompensated hypothyroidism that

usually occurs after a period of longstanding, unrecognized or poorly controlled thyroid

hypofunction and is often precipitated by a superimposed systemic illness. Such precipitating

or exacerbating factors include infection, trauma, certain medications, hypothermia,

cerebrovascular accident, congestive heart failure, metabolic disturbances, and electrolyte

abnormalities [1-3]. If left untreated, the clinical course is one of multi-organ dysfunction with

characteristic lethargy progressing to altered sensorium (stupor, delirium, and coma).

Hypothermia is a key early manifestation in most patients and may be quite profound (less

than 26° C). Respiratory depression leading to hypoventilation and hypercapnia may](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-3-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

necessitate intubation and mechanical ventilation. Decreased cardiac contractility,

bradycardia, cardiomegaly, and arrhythmias may lead to hypoperfusion and cardiogenic

shock. Other common abnormalities seen in patients with myxedema coma include

gastrointestinal dysfunction, renal impairment, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, hypoxemia and

anemia [1].

The diagnosis of myxedema coma is usually based on clinical manifestations, a history of

moderate to severe hypothyroidism, and is confirmed by laboratory testing, with elevated

serum thyrotropin (TSH), and decreased total and free thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine

(T3). Early diagnosis, supportive care, and treatment with intravenous thyroxine have been

shown to improve outcomes [4]. Recent reports including prospective studies [2, 3, 5] have

focused on establishing predictors of poor outcome in patients with myxedema coma.

Coma on admission, lower GCS (Glasgow Coma Scale) score and an APACHE II (Acute

Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) score of < 20 were demonstrated to be reliable

predictors of higher mortality in the prospective study of Rodriquez et al. [2] of 11 patients

with myxedema coma. They also noted that the mean age of survivors was lower than that of

non-survivors, albeit not statistically significantly. Heart rate, body temperature, mean free

T4, and mean TSH did not differ between survivors and non-survivors. Dutta et al [3], in a

report of 23 patients with myxedema coma, found hypotension and bradycardia on admission,

need for mechanical ventilation, hypothermia unresponsive to treatment, sepsis, intake of

sedative drugs, lower GCS score, and high APACHE II and SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure

Assessment) scores highly predictive of a poor outcome. Results from a Medline search of 82](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-4-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

cases of myxedema coma [5] revealed that older age, cardiac complications, such as

hypotension and sinus bradycardia with low voltage QRS, and high dose thyroid hormone

replacement during treatment for myxedema coma were associated with a fatal outcome after

1 month of therapy. There was no significant difference in mortality based upon the APACHE

II score and the presence of pulmonary complications.

The diagnosis of myxedema coma is mainly clinical, with no clear cut criteria that might

distinguish either hypothyroidism alone or coma of other etiologies from true myxedema

coma. In view of the high morbidity and mortality of myxedema coma [2], the development

and application of criteria for its identification could allow earlier diagnosis and treatment that

may have a salutary effect on prognosis for recovery and outcome. [4]

Materials and Methods

Study population

Our study population was based on all patients age 18 years and older who presented to

MedStar Washington Hospital Center (MWHC), Washington DC and Veterans Affair (VA)

Medical Center, Washington DC from 1989 to 2009, with an admitting or discharge diagnosis

of myxedema coma.

Definitions

The following definitions and grading systems were employed: hypothermia was defined as a

temperature lower than 35°C. Bradycardia was defined as heart rate less or equal to 60 beats

per minute and hypotension as blood pressure less than 90/60 mmHg, or a mean arterial](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-5-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

pressure less than 70. Neurological findings were graded based on the severity of mental

status changes, from somnolence to obtundation, stupor and coma. Obtundation was defined

as less than full mental capacity, but still easy arousable with persistence of alertness for brief

periods of time [1]. Stupor was applied to the state of lack of critical cognitive function and

level of consciousness, responsiveness only to painful stimuli, while coma was considered to

be the state of complete lack of responsiveness. Hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose

level < 60 mg/dL and hyponatremia was classified as a serum sodium < 135 mEq/L . To

define hypoxemia we used a threshold for oxygen saturation at room temperature of less than

88% or pO2 less than 55 mmHg, while hypercapnia was indicated by a pCO2 level of 50

mmHg or greater. The diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism was based on levels of total or

free thyroxine (T4) below the reference range together with an elevated serum TSH.

Reference ranges were as follows: total T3 71-180 ng/dL, total T4 4.5 -12 ug/dL, free T4 0.8 -

1.7 ng/dL, and TSH 0.45 – 4.5 mIU/L.

Methodology

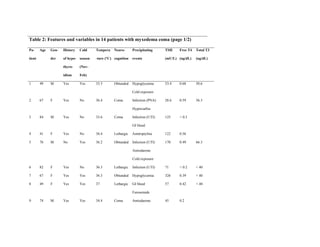

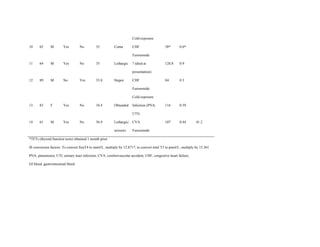

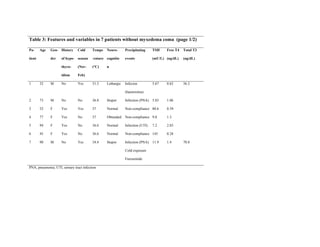

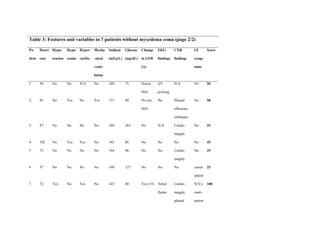

Each chart was retrospectively reviewed (by GP and TC) to note patient demographics and the

clinical manifestations of myxedema coma in each patient on presentation. The following

characteristics were recorded for each patient: demographics (gender, age, race, past medical

history, to include history of hypothyroidism, or thyroid surgery, medications, medication

non-compliance), vital signs at the time of MC diagnosis (temperature, heart rate, respiratory

rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation), respiratory status (supplemental oxygen, mechanical

ventilation), neurological status (somnolence, lethargy, obtundation, stupor, coma, seizures),

gastrointestinal manifestations (anorexia, abdominal pain, constipation, decreased/absent

intestinal motility), laboratory findings (complete metabolic panel, TSH, free T4 and total T3,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-6-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

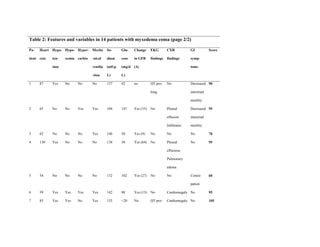

whereas a score of 60 had a predictive probability of 0.55, with an odds ratio of 1.22. The

model overall was significant (Chi-square test p-value = 0.0006).

The area under the ROC curve of the prediction score was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.65 – 1.00) (Fig 1).

The cutoff point on ROC curve corresponded to the score of 60, which had the highest

sensitivity (100%) and specificity (85.71%), with a positive likelihood ratio of 7.0 and

negative likelihood ratio of 0.0. The score of 45 had 100% sensitivity, but a lower specificity

of 42.86%, whereas a score of less than 25 had 0% specificity (Fig 1).

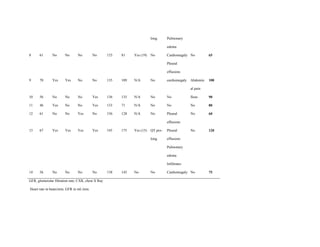

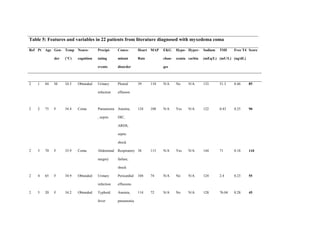

When applied to patients in the literature for whom enough clinical data were available, the

diagnostic scoring system identified 16 out of 22 patients as having myxedema coma (score ≥

60) (Table 5). The remaining six patients would have been classified as being at risk for

myxedema coma (scores ranged between 45 - 55), but did not quite meet the criteria for a

diagnosis of myxedema coma. None of the twenty two patients had scores at presentation that

qualified them as unlikely to have myxedema coma.

Discussion

Although it is generally accepted that the diagnosis of myxedema coma should rely on some

degree of mental status alteration, impaired thermoregulatory response and the presence of a

precipitating event [6], clear cut diagnostic criteria to define myxedema coma have not been

established. Moreover, uncertainty of diagnosis is suggested by the numerous hypothyroid

patients with presumed myxedema coma reported in the literature in whom at least one of

these features was minor or absent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-10-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

Although altered mental status was a prominent aspect of the presenting clinical picture in all

our patients, it would be tenuous to base a diagnosis on this alone. There may be innumerable

etiologies for mental status change, but it is through combination with other signs and

symptoms of our scoring system, along with thyroid function test results, that the mental

status changes allow a more precise focus on the diagnosis of myxedema coma.

To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports of clinical algorithms to define

diagnostic criteria for myxedema coma, likely due to the paucity of cases and consequent

lack of studies to address this issue. Accordingly, we have developed a diagnostic scoring

system for myxedema coma, and assessed its potential utility in a cohort of patients from our

two institutions, as well as applying it to selected patients identified in the literature [2, 13-

23]. Our hope is that this scoring system will enable earlier diagnosis and treatment of

patients with myxedema coma.

Importantly, most of the patients whom we evaluated from the literature were likely

“underscored” due to limited clinical data availability. Thus, an assigned score of 60 could

easily have been achieved with one or two more variables being present, such as the lacking

details of metabolic abnormalities, EKG changes, and/or gastrointestinal manifestations.

Patient 14 [Table 5] [15] was of particular interest, as she initially presented to the hospital

with biochemical evidence of subclinical hypothyroidism, and clinical features that would not

have diagnosed her with myxedema coma, given a score of 40. Shortly after admission, her

clinical status deteriorated and she was diagnosed with myxedema coma, achieving a score of

80, based on our diagnostic scale. Of note, the patient’s biochemical markers continued to

reflect a state of subclinical hypothyroidism throughout her hospitalization, showing that a

reliance on thyroid function tests alone could have potentially missed the development of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-11-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

and lethargy to slow mentation, confusion, cognitive dysfunction, minimal responsiveness, or

coma. The decompensated neurologic state may be primary, such as from a cerebrovascular

event or due to a drug overdose with sedatives or hypnotics; whereas sepsis, hyponatremia, or

other metabolic disturbances are secondary events, which may worsen the cognitive function.

Homeostatic dysfunction resulting from thyroid hormone deficiency is generally insufficient

to cause myxedema coma, as the body can compensate through neurovascular mechanisms. A

triggering event is usually required to overcome the compensatory mechanisms in a

hypothyroid patient. [7] Infection, cerebrovascular or cardiovascular events, cold temperature

exposure, medications such as amiodarone, beta blockers, lithium, narcotics, sedatives,

diuretics, and metabolic derangements are several examples of such insults. [2, 3] Each

patient had at least one identifiable precipitating event and the frequency of these events was

in concordance with the findings reported in other studies. [3]

Prolonged untreated hypothyroidism coupled with a triggering event may lead to

cardiovascular collapse and shock which may not be responsive to vasopressor therapy alone,

until thyroid hormone also is administered [8]. Electrocardiographic abnormalities such as

bradycardia, low voltage, nonspecific ST wave inversion, QT prolongation, as well as rhythm

abormalities may be seen [9]. Hypotension was commonly seen in our myxedema coma cases,

and the frequency of electrocardiographic abnormalities was similar to that reported in the

literature [3].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-13-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

An impaired ventilatory response and a need for mechanical ventilation are common

manifestations in patients with myxedema coma. Decreased respiratory center sensitivity to

hypercarbia and hypoxemia may lead to hypoventilation, which may be aggravated further by

impaired respiratory muscle function, obesity, and other obstructive processes of the airway

such as macroglossia, myxedema of the larynx and nasopharynx, intrinsic processes such as

pneumonia, reduced lung volumes, or extrinsic compressive processes such as pleural

effusions [1, 10, 11].

Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in hypothyroid patients is a result of decreased renal

plasma flow withwater retention and hyponatremia usually being concomitant findings in

these patients [12]. Fluid extravasation, resulting from altered vascular permeability, may

present as effusions, nonpitting edema and anasarca. Effects of profound thyroid hormone

deficiency on the gastrointestinal system may include decreased intestinal motility with

constipation and may progress to paralytic ileus with a quiet and distended abdomen,

anorexia, nausea and abdominal pain [23]. In our patients, the metabolic abnormalities

occurred with relative equal frequencies but independent of each other, suggesting the

importance of appreciation of the multisystemic basis for development of myxedema coma.

The ultimate diagnosis of myxedema coma should be made with biochemical evidence of low

levels of serum free T4 and T3, and elevated TSH in patients with primary hypothyroidism,

whereas in secondary hypothyroidism the biochemical diagnosis should rely on low, or

normal TSH, and low free T4 and total T3 hormone levels and evidence of pituitary

dysfunction. None of our patients had biochemical evidence of secondary hypothyroidism.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-14-320.jpg)

![DOI:10.4158/EP13460.OR

© 2013 AACE.

Particular attention should be given to patients with biochemical evidence of secondary

hypothyroidism that could be difficult to distinguish from the “sick euthyroid” state. The latter

entity represents a physiologic adaptive response of the thyrotropic feedback control to severe

illness, and is reflected by biochemical evidence of normal, low, or slightly elevated TSH,

depending of the severity of the illness, and low free T4 and T3. Therefore, in order to avoid

misclassifying patients with “sick euthyroid” syndrome as having myxedema coma in the

setting of commonly present multiorgan dysfunction, we suggest that appropriate diagnosis of

secondary hypothyroidism should be done first, either from history of hypothalamic-pituitary

dysfunction, or through imaging studies reflecting organic hypothalamic, or pituitary disease.

This study is limited by virtue of its retrospective design and relatively small sample size,

which precluded accurate comparison between groups due to lack of statistical power. Also,

due to insufficient published data in all the case reports of myxedema coma assessed from

literature, it was not possible to fully validate the scoring system. However, the score

demonstrated to have positive predictive value and a high discriminative power.

In conclusion, considering the complex, multisystemic manifestations of hypothyroidism in

patients with myxedema coma and the high mortality associated with delays in therapy, a

practical guide to earlier diagnosis could be of value. We propose a diagnostic scoring system

for myxedema coma based upon data from restrospective cases diagnosed at our institutions,

as well as from selected case reports culled from the literature. This scoring system assessed

an array of the diagnostic features associated with myxedema coma and found a similar

frequency of findings in our cohort of patients as in those assessed from the literature [2, 3, 5].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comamixedematososcore-160515205126/85/Coma-mixedematoso-score-15-320.jpg)