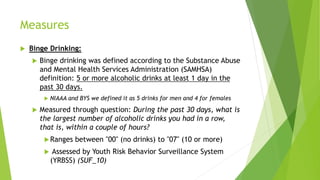

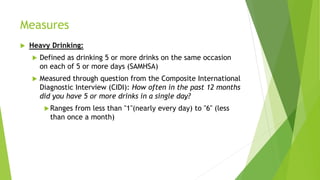

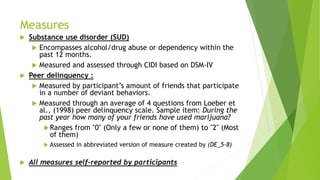

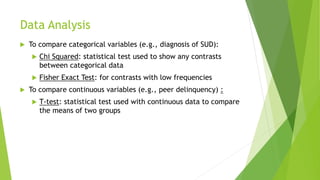

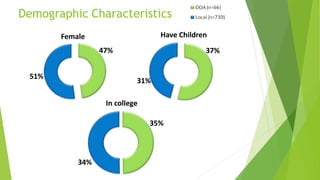

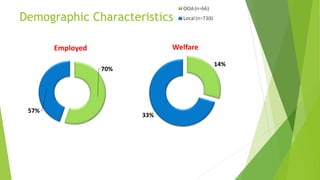

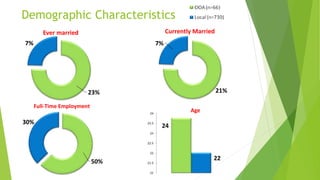

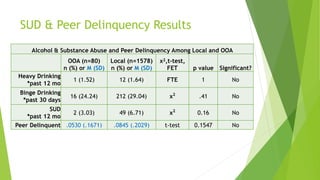

This document summarizes a study examining substance use differences between Puerto Rican youth who remained in the New York City area versus those who moved out of the area. The study found significant demographic differences between the two groups, with those who moved out of the area more likely to be older, married, employed, and less reliant on welfare. However, the study found no statistically significant differences in substance use, binge drinking, substance use disorders, or number of delinquent peers between the two groups. Limitations of the study included a small sample size of those who moved out of the area.