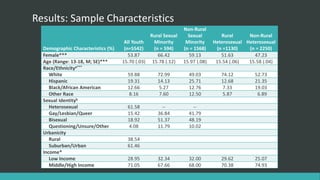

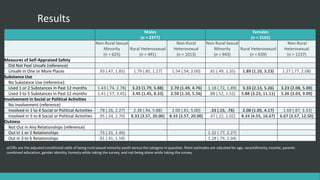

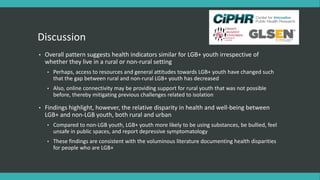

Rural and non-rural sexual minority youth showed similar health indicators, with a few exceptions. Rural sexual minority youth reported poorer mental health, lower safety, and higher substance use than both rural and non-rural heterosexual youth. Compared to heterosexual youth, sexual minority youth were more likely to be involved in social or political activities, perhaps to connect with a supportive community. While urbanicity may no longer confer differences for sexual minority youth, their sexual identity remains associated with greater health risks regardless of rural or non-rural location.