The document includes an assignment on absorption and marginal costing for a manufacturing company, detailing questions related to production costs and inventory. Additionally, it presents an overview of the book 'Working Through Conflict' which explores conflict theory and management strategies, covering various settings and providing real-life case studies. The authors emphasize an interdisciplinary approach to understanding conflict as a communication phenomenon, with new research and resources included in the eighth edition.

![identity and rigidly differentiate

themselves from other groups, while those with an inclusive

identity orientation do not see

the world in terms of groupings as much. Kim further argues

that individuals differ in terms

of their identity security,—the overall feelings of self-

confidence and self-efficacy that they

have. Individuals with exclusive identity orientations and low

identity security are more likely

to engage in dissociative behavior, based on the presumption of

tension between social groups

“which contribute[s] to a temporary state of conflict, or

‘coming-apart’ ” of relationships.

Individuals with inclusive identity orientations and high

identity security are more likely to

engage in associative behavior, those which foster

understanding, cooperation, and intimacy,

“’the coming-together’ of the involved parties” (p. 648).

Case 3.5 considers how social identity processes could have

figured in the Parking Lot

120

Scuffle if they were triggered.

Case Study 3.5 Intergroup Conflict Dynamics and the

Parking Lot Scuffle

Jay and Tim are from the same cultural group, so intergroup

dynamics do not explain the

Parking Lot Scuffle very well. Suppose, however, that Jay and

Tim had been from

different groups—for example, they were of different genders,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-264-320.jpg)

![together, for instance, will

enable members of each group to see members of the other

group as individual human

beings like themselves, hence undermining engrained attitudes

and stereotypes.

The “contact hypothesis” was originally advanced by the

eminent social psychologist

Gordon Allport (1954). His research indicated that contact will

reduce intergroup

prejudice most effectively if (a) it is handled so that it fosters

“social norms that favor

intergroup acceptance, (b) the situation has high ‘acquaintance

potential,’ promoting

intimate contact among members of both groups, (c) the contact

situation promotes equal

status interactions among members of the social groups, and (d)

the situation creates

conditions of cooperative interdependence[what Deutsch called

promotive

interdependence] among members of both groups” (Brewer &

Gaertner, 2003; italics

added).

Research has generally shown that contact under the conditions

defined by Allport

does create more positive attitudes toward members of the out-

group (Brewer &

Gaertner, 2003). However, these attitudes do not necessarily

translate to less prejudice or

undermine stereotypes about other social groups as a whole. In

some cases, positive

attitudes created by intergroup contact only attach to the

specific people involved. They

are regarded as exceptions, and the positive attitudes are not

generalized to their entire](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-268-320.jpg)

![else. This is common in conflicts

in organizations: by handing off the conflict to a superior or to

another unit in the

organization, the party tries to make it someone else’s problem.

Withdrawing is more subtle

and flexible than protecting.

A third variation of avoiding is smoothing, in which the party

plays down differences and

emphasizes issues on which there is common ground. Issues that

might cause hurt feelings or

arouse anger are avoided, if possible, and the party attempts to

soothe these negative

emotions. Smoothers accentuate the positive and emphasize

maintaining good relationships.

Roloff and Ifert (2000) marshal evidence that the positive affect

associated with smoothing is

likely to diminish the negative impacts of avoiding.

Avoiding styles may be useful if chances of success with

collaborating or compromising are

slight and if parties’ needs can be met without surfacing the

conflict. For example, avoidance

has been shown to improve team effectiveness by eliminating a

distraction that would

otherwise derail progress on an issue (De Dreu & Van Vianen,

2001). Sillars and Weisberg

(1987) reported that some satisfied couples engaged in avoiding

through “topic shifts, jokes,

denial of conflict [and] abstract, ambivalent, or irrelevant

comments” (p. 86). These couples

used avoiding in order to fulfill their needs for autonomy and

discretion. In a similar vein,

Zhao et al. (2012) found that some users avoided conflict by

adjusting the privacy settings on

their social media accounts so that their partners could not see](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-305-320.jpg)

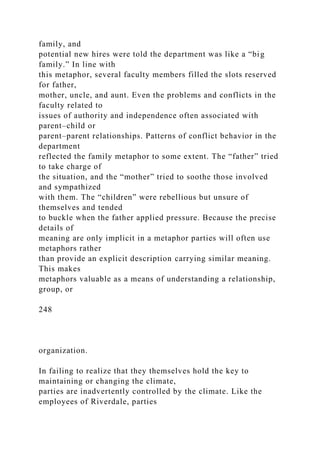

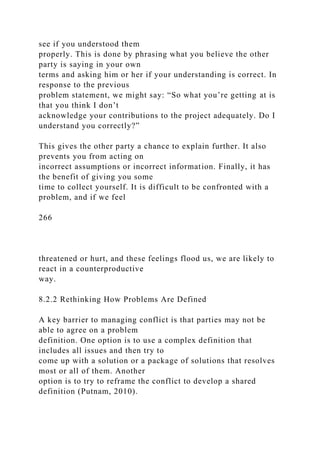

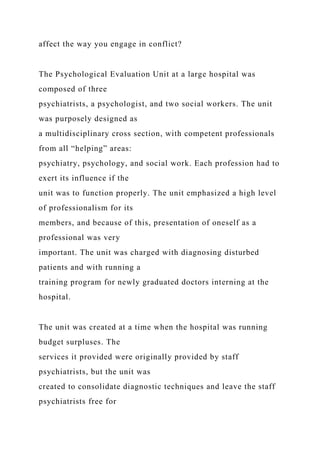

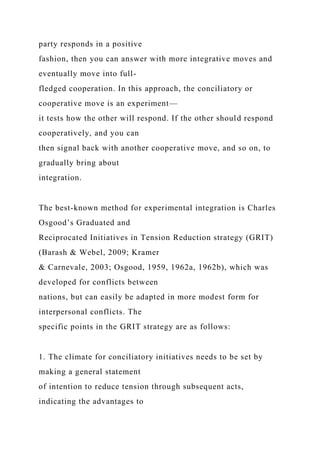

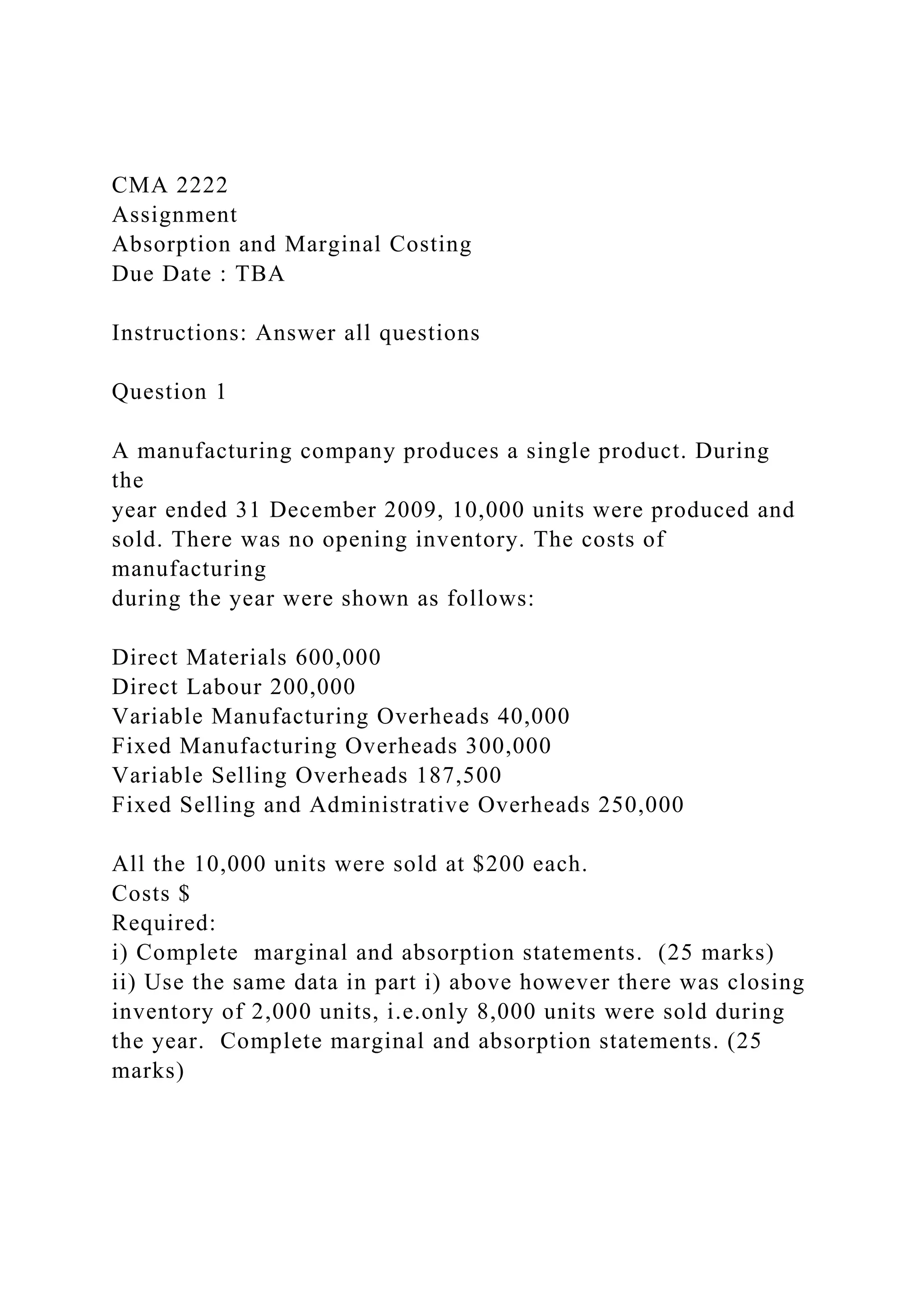

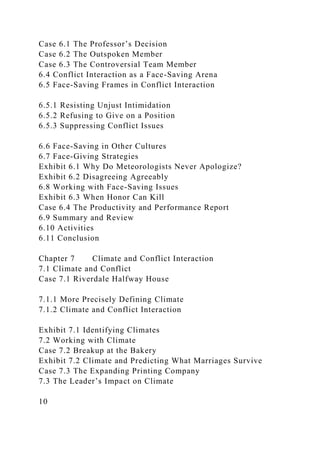

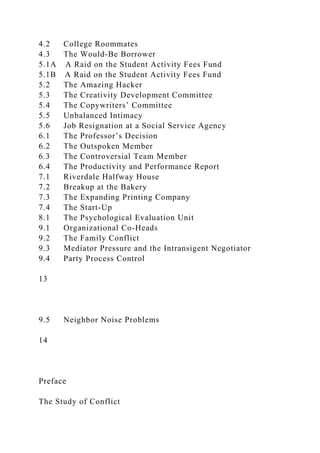

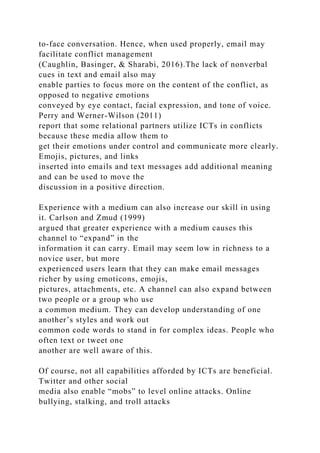

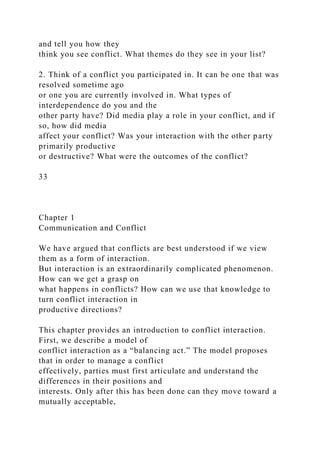

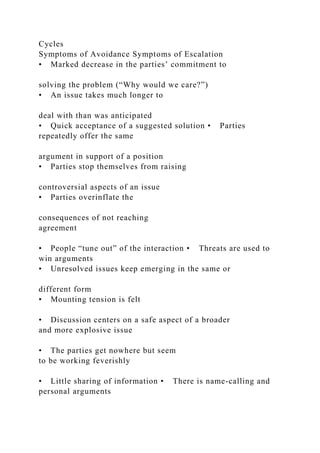

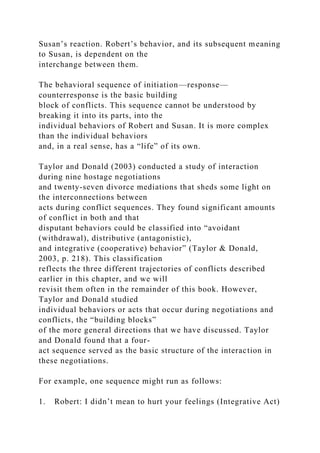

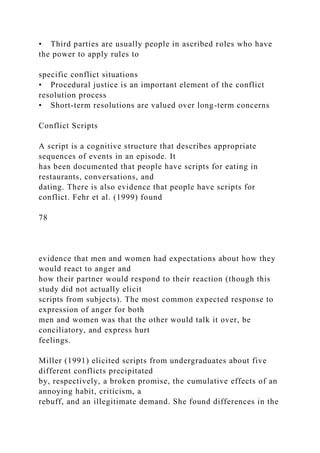

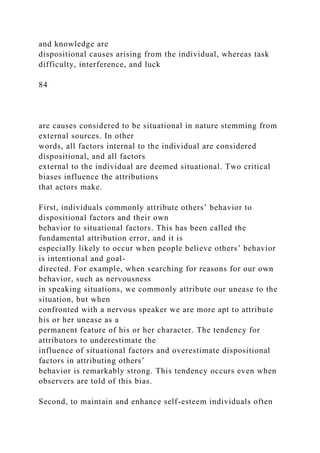

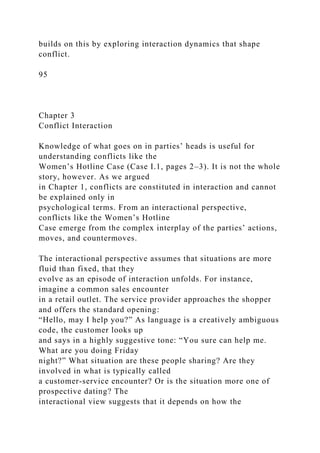

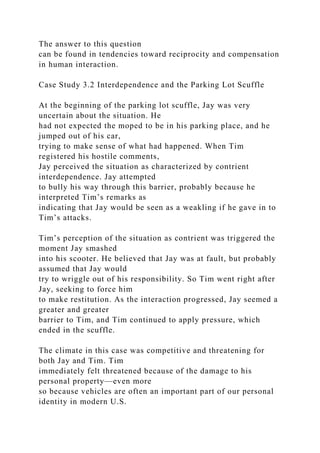

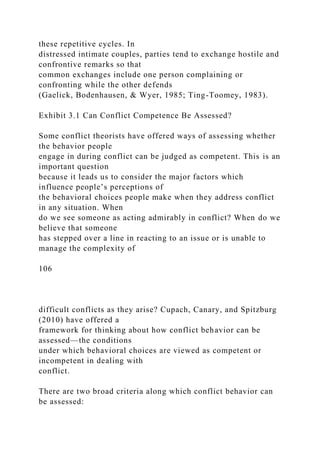

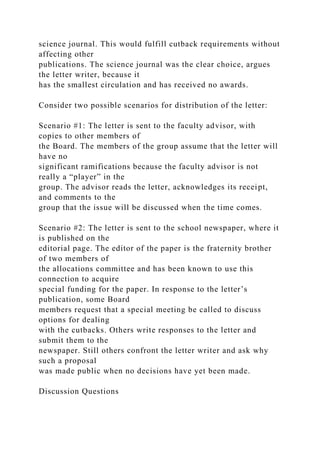

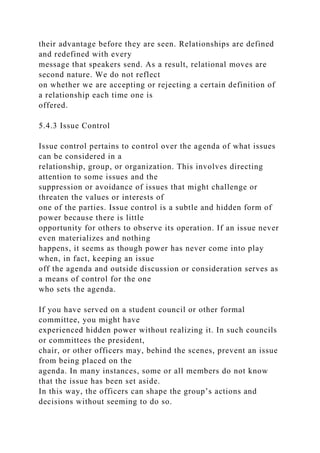

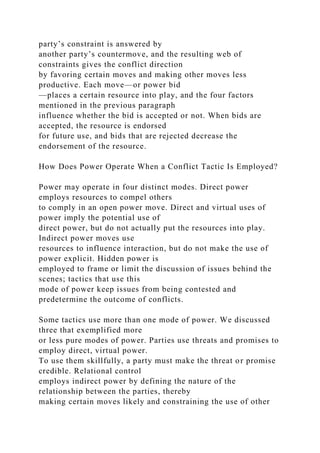

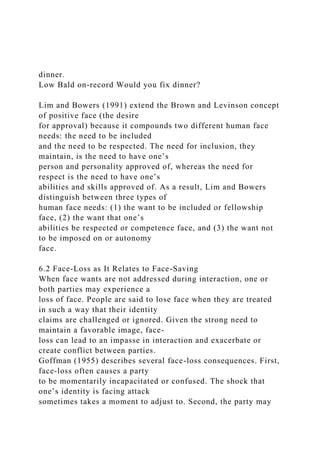

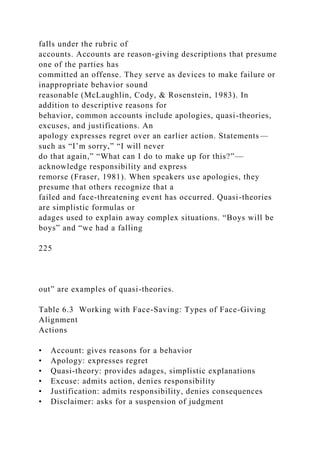

![withholding endorsement of the

resources it’s based on? In principle, weaker parties always

have this option, but it is not an

easy option to exercise for two reasons. First, resistance often

entails real costs and harm—

physical, financial, and/or psychological—to the weaker party.

Second, the tendency to

endorse power is deep seated and based in powerful and

pervasive social processes, as we will

see when we consider the other “deeper” form of power.

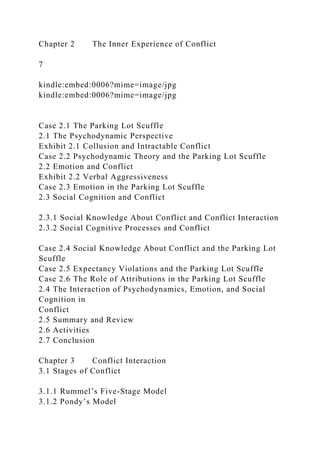

At the most superficial level, we endorse power because others’

resources enable them to

grant or deny things that are valuable. As Richard Emerson

(1962) stated in a classic analysis

of power: “[The] power to control or influence the other resides

in control over the things he

values, which may range all the way from oil resources to ego-

support” (p. 11). This is an

important, if obvious point, and it leads to a more fundamental

issue: control is exerted during

interaction. One party makes a control bid based on real or

potential use of resources, and the

other party accepts or rejects it.

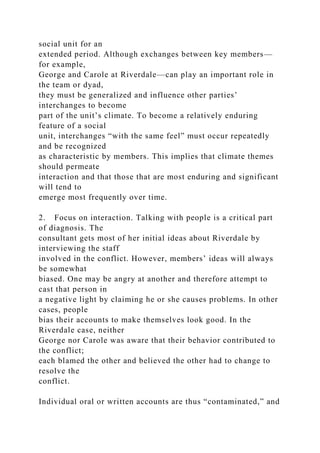

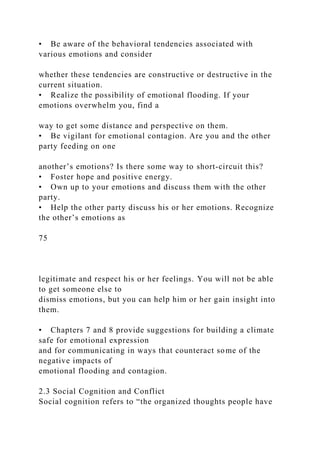

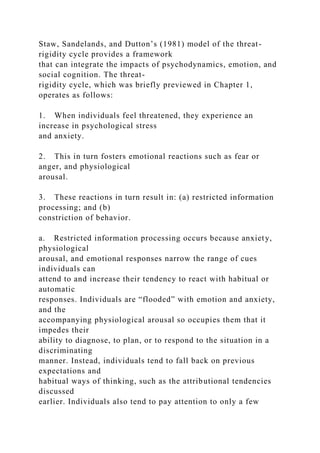

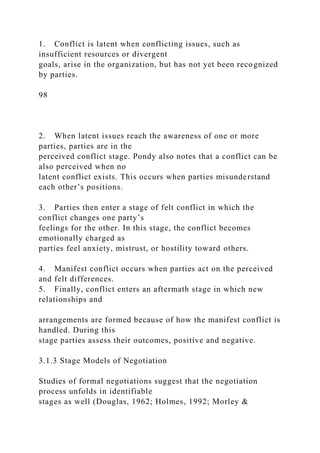

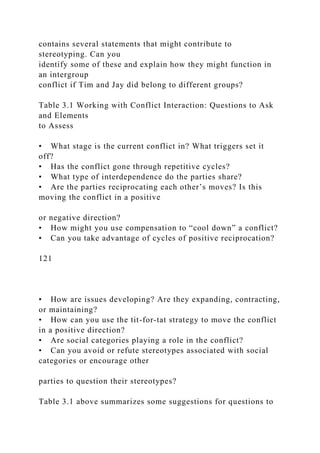

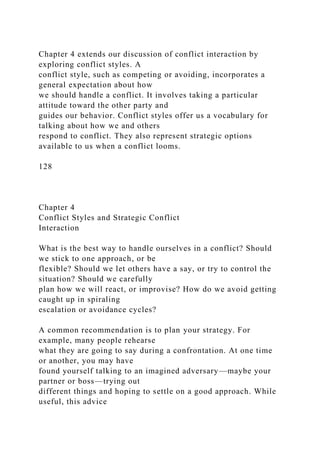

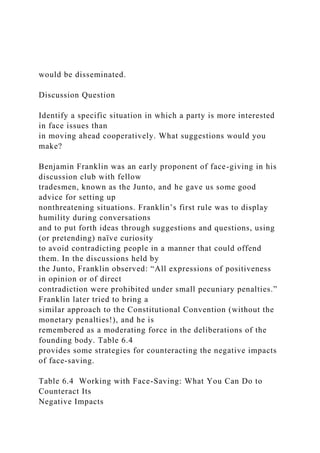

Table 5.1 Power Resources in Relationships, Groups, and

Organizations

The other’s liking/love for party

The other’s respect for party

Formal authority over the other

Information

Education, certifications, training, expertise

Ability to solve problems no one else can solve

Control of scarce resources (money, technologies, etc.)

Control over rewards for other party](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-378-320.jpg)

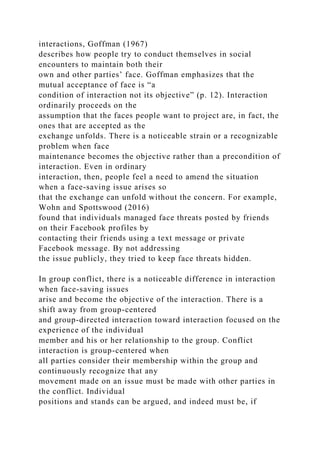

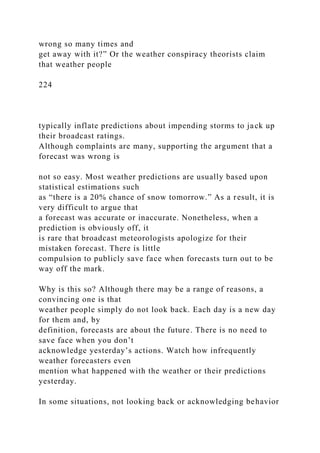

![want to be seen by those they encounter as possessing certain

traits, skills, and qualities. They

constantly position themselves in interaction with others (Harre

& van Langenhove, 1999). In

short, face is the communicator’s claim to be seen as a certain

kind of person. As one scholar

in the area puts it, face is “the positive social value a person

effectively claims for himself [sic]

by the line others assume he has taken during a particular

contact” (Goffman, 1955). Face

concerns are known to be important across all cultures (Oetzel,

Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008;

Ting-Toomey, 2005).

The concept of face can be traced to fourth-century B.C. China.

The Chinese distinguish

between two aspects of face, lien and mien-tzu (Hu, 1944). Lien

stands for good moral

character. A person does not achieve lien, but rather is ascribed

this quality unless he or she

behaves in a socially unacceptable manner. To have no lien

means to have no integrity, which

205

is perhaps the most severe condemnation that can be made of a

person. Mien-tzu reflects a

person’s reputation or social standing. One can increase mien-

tzu by acquiring social

resources such as wealth and power. To have no mien-tzu is

simply to have floundered

without success, an outcome that bears no social stigma.

6.1 The Dimensions of Face](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-463-320.jpg)

![matters. George’s investigation

did not reveal any problems, but it embarrassed the staff

members (who had been

manipulated by prisoners) and made Carole feel that George did

not respect her. George

admitted his mistake and hoped the incident would blow over.

Ten months after George arrived at Riverdale, the climate had

drastically changed.

Whereas Riverdale had been a supportive, cohesive work group,

it was now filled with

tension. Interaction between George and the staff, particularly

Carole, was formal and

distant. While the staff had to some degree pulled together in

response to George, its

cohesiveness was gone. Informal communication was down, and

staff members received

much less support from each other.

A consultant was called in to address the problems. As the third

party observed, “[T]he

staff members expected disrespect from each other.” They felt

stuck with their problems

and believed there was no way out of their dilemma. There was

no trust and no sense of

safety in the group. Members believed they had to change others

to improve the situation

and did not consider changing themselves or living with others’

quirks.

241

The staff wanted George to be less authoritarian and more open.

George wanted the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-549-320.jpg)

![staff to let him blow up and then forget about it. There was

little flexibility or willingness

to negotiate. As Carole observed, each contact between herself

and George just seemed to

make things worse, “[S]o what point was there in trying to talk

things out?” The

consultant noted that the staff seemed to be unable to forget

previous fights. They

interpreted what others said as continuations of old conflicts

and assumed a hostile

attitude even when one was not present.

The third party tried to get the group to meet and iron out its

problems, but the group

wanted to avoid confrontation—on several occasions scheduled

meetings were postponed

because of other “pressing” problems. Finally, George found

another job and left

Riverdale, as did one of the counselors. Since then, the staff

reports that conditions have

considerably improved.

Discussion Questions

At what points in this conflict could a significant change in

climate have

occurred? What alternatives were available to staff members at

these points?

To what extent do you feel that this group’s climate was

inevitable?

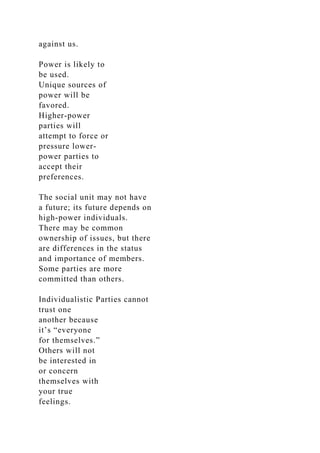

A quick perusal of Case 7.1 indicates that a contrient

(competitive) climate prevailed after

George replaced the previous director. George and Carole were

each trying to protect their

own “turf.” Relationships among employees were distrustful,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cma2222assignmentabsorptionandmarginalcostingduedate-221025211143-173d0030/85/CMA-2222Assignment-Absorption-and-Marginal-CostingDue-Date-docx-550-320.jpg)