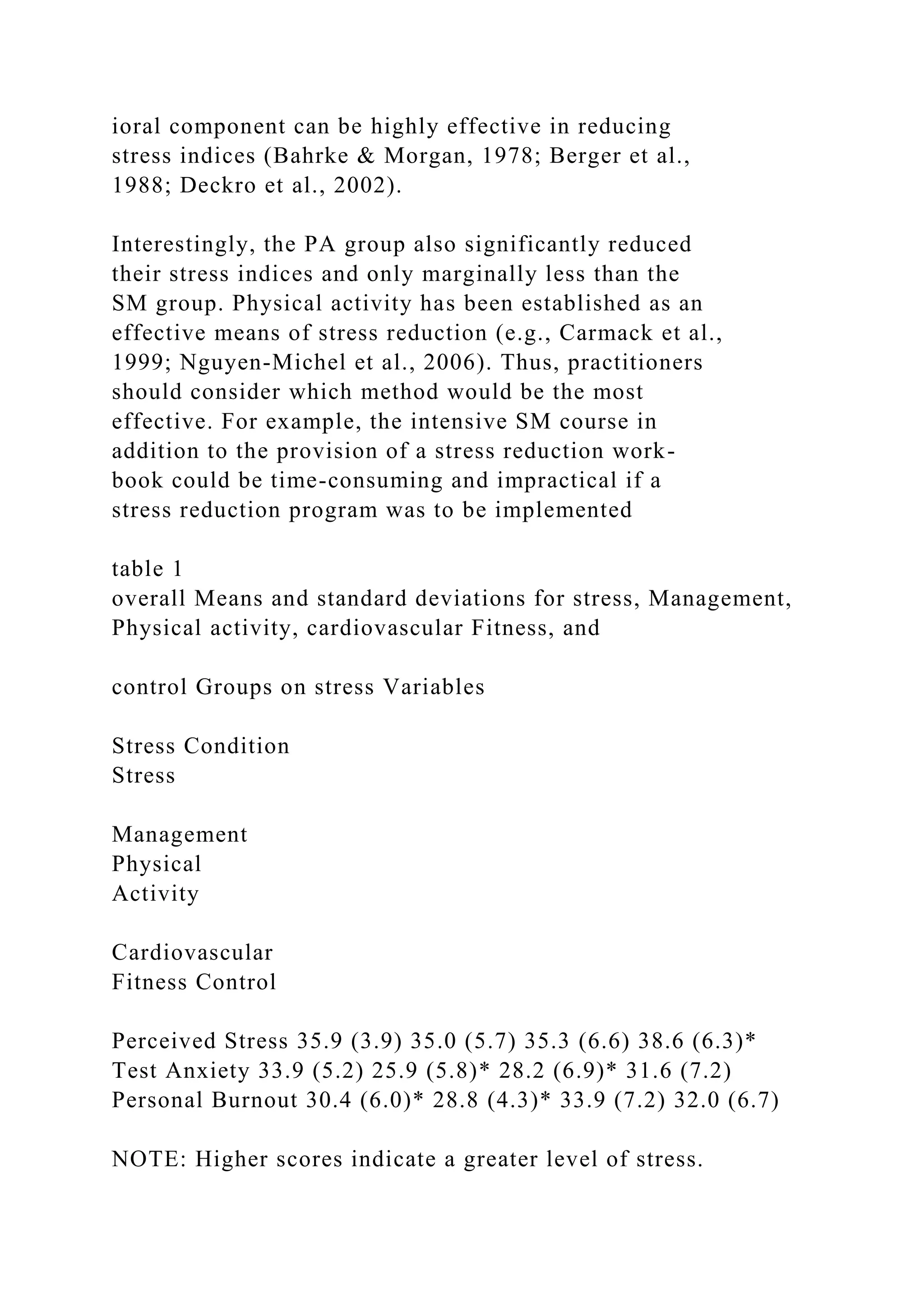

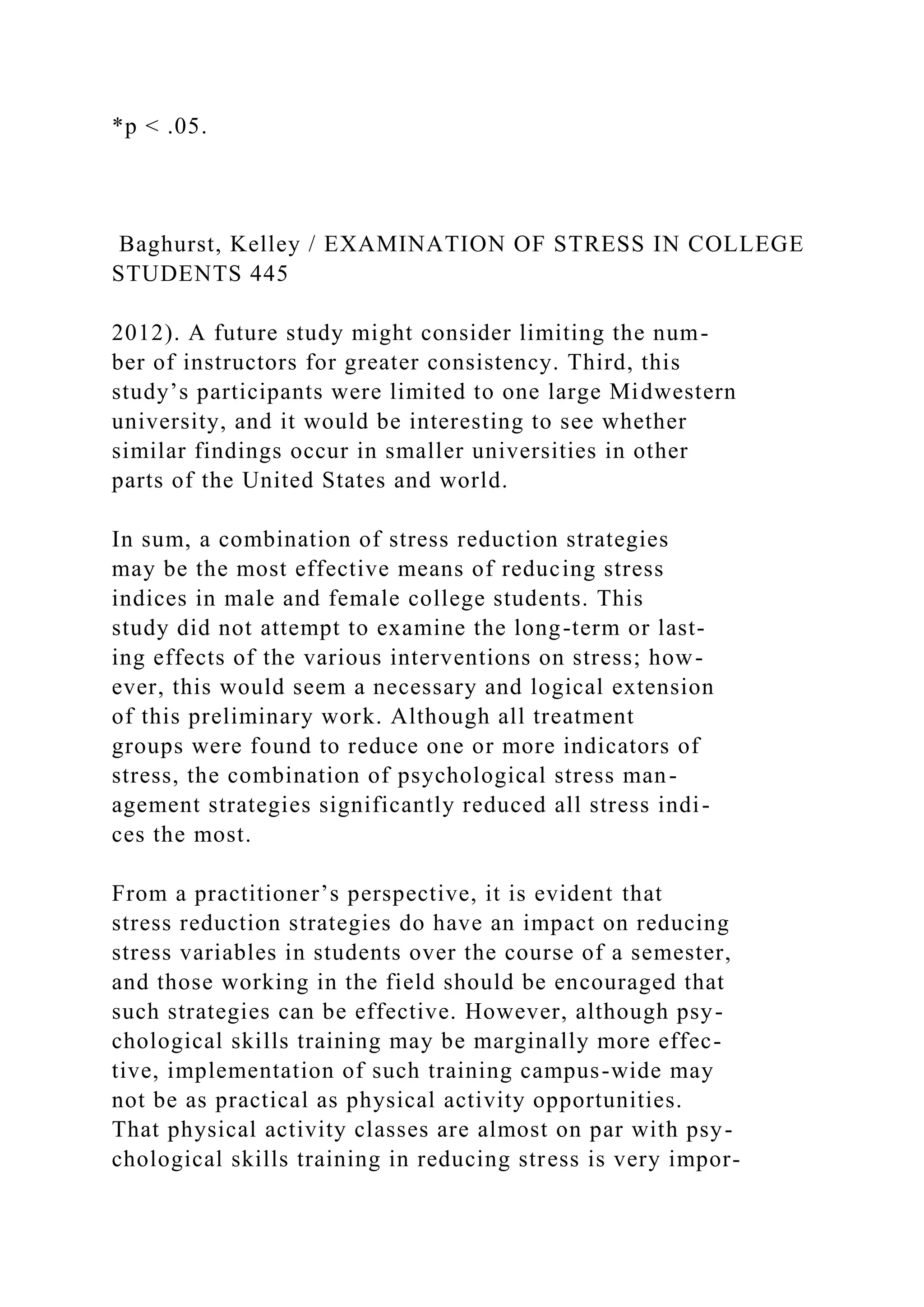

The document discusses the importance of citations and references in academic writing, particularly in the context of stress management among college students. It highlights research on the effectiveness of various stress reduction interventions, including cognitive-behavioral techniques and physical activity, which showed significant improvements in perceived stress, test anxiety, and personal burnout among participants over a semester. The study aimed to identify which intervention methods might be most effective in reducing stress levels among college students.

![An Examination of Stress in College Students Over

the Course of a Semester

Timothy Baghurst, PhD1

Betty C. Kelley, PhD2

Authors’ Note: Address correspondence to Timothy Baghurst,

Health and Human Performance, Oklahoma State University,

189

Colvin, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA; e-mail: [email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1177%2F15248399

13510316&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2013-11-14

Baghurst, Kelley / EXAMINATION OF STRESS IN COLLEGE

STUDENTS 439

to its demands. It is a transaction between the environ-

ment or situation and the person, which results in the

perception or cognitive appraisal that the demands of

the situation exceed the individual’s resources availa-

ble to meet or cope with those demands (Kelley, 1994;

Lazarus, 1990). Life stressors may be transient, such as

annoying everyday hassles, or more long term and

potentially traumatic.

Response to such stressors is influenced by both the

way in which events are appraised and an individual’s

effective response capacity. People who sense that they

have the ability and the resources to cope are more

likely to take stressors in stride and take action con-

structively. However, experiences that consistently

lead to a negative stress appraisal can cause both](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/citationsandreferencingyoursourcecitationsin-textcitation-221112063817-b0b39c83/75/Citations-and-Referencing-your-sourceCitationsIn-text-citation-docx-5-2048.jpg)