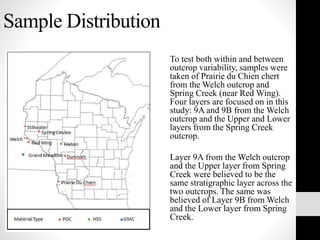

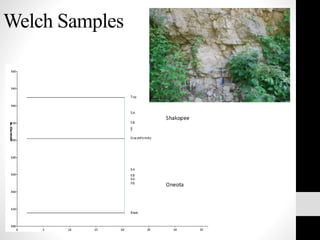

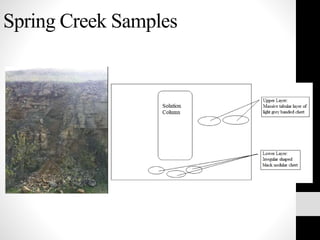

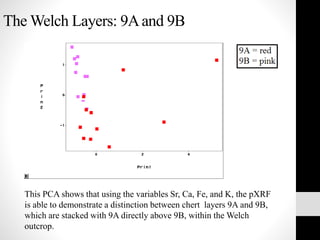

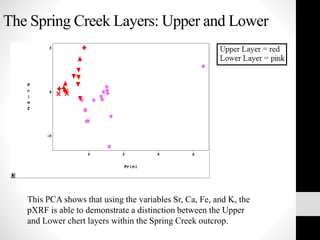

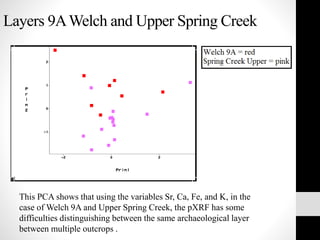

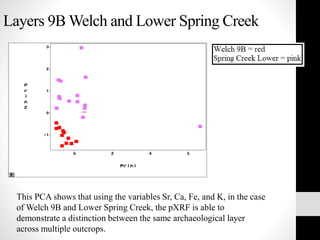

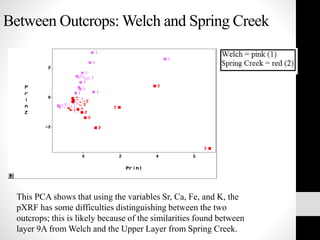

The document summarizes a study that used portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (pXRF) to analyze chert samples from different layers and outcrops in order to determine if pXRF could distinguish between the samples. The study found that pXRF could distinguish between layers within the same outcrop based on elemental composition. It also found it could distinguish the same layers between outcrops for one pair of layers but not another. Overall, pXRF showed potential for sourcing chert but more research is needed to determine its effectiveness between unrelated outcrops.

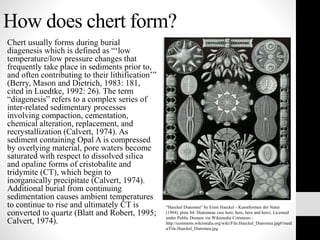

![How does chert form?

Bedded Cherts

This style of chert generally occurs

when the ratio of opaline material to

water is high. Bedded cherts form

predominantly in deep, elongated

sedimentary basins (or more rarely in

small basins with restricted

circulation that generate localized

areas of highly concentrated opaline

silica).

Nodular Cherts

This style of chert deposit occurs

as nearly spherical to irregular

shaped concretions within

carbonate sediments that formed

as secondary features during the

migration of silica rich waters

with very high alkalinity (Blatt

and Robert, 1995; Prothero and

Schwab, 2004).

The Children's Museum of Indianapolis [CC BY-SA 3.0

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chertsourcingusingportablexrf-150316152923-conversion-gate01/85/Hand-held-Portable-X-ray-Fluorescence-Spectrometry-HHpXRF-or-pXRF-for-Sourcing-and-Distinguishing-Chert-6-320.jpg)