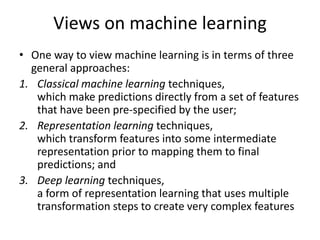

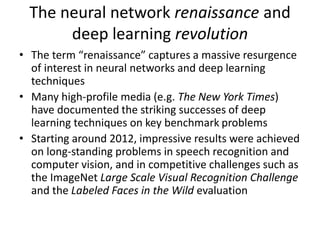

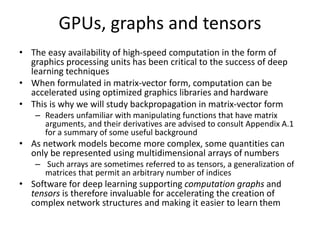

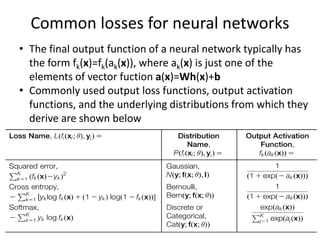

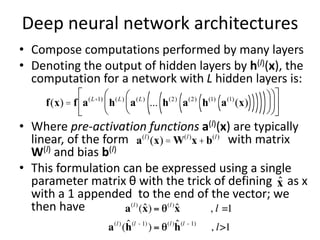

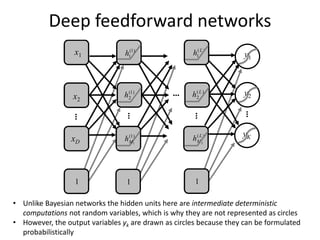

The document discusses deep learning techniques. It introduces deep learning and its impact on fields like speech recognition and computer vision. Deep learning uses large datasets and high-capacity models with many parameters to exploit information in data more effectively than traditional machine learning. The document also discusses key developments in deep learning like increased data, deeper network architectures, and accelerated training with GPUs. It provides examples of common neural network architectures, losses, and activation functions used in deep learning.

![Backpropagation in matrix vector form

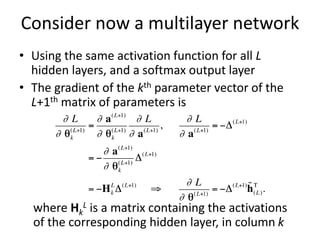

• Backpropagation is based on the chain rule of

calculus

• Consider the loss for a single-layer network with a

softmax output (which corresponds exactly to the

model for multinomial logistic regression)

• We use multinomial vectors y, with a single

dimension yk = 1 for the corresponding class label

and whose other dimensions are 0

• Define , and ,

where θk is a

column vector containing the kth row of the

parameter matrix

• Consider the softmax loss for f(a(x))

f =[ f1(a), … , fK (a) ]T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-21-320.jpg)

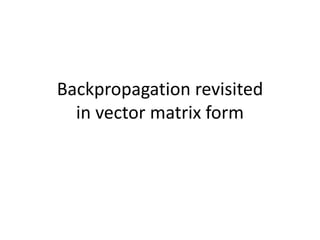

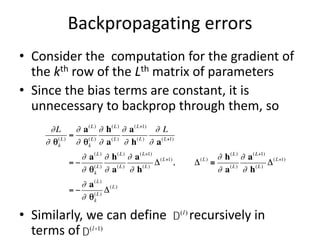

![Matrix vector form of gradient

• We can write

and since

we have

• Notice that we avoid working with the partial

derivative of the vector a with respect to the matrix θ,

because it cannot be represented as a matrix — it is a

multidimensional array of numbers (a tensor).

¶ L

¶ a

= - y-f(x)

[ ]º -D](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-23-320.jpg)

![Momentum

• As with regular gradient descent, ‘momentum’ can

help the optimization escape plateaus in the loss

• Momentum is implemented by computing a moving

average:

– where the first term is the current gradient of the loss

times a learning rate

– the second term is the previous update weighted by

• Since the mini- batch approach operates on a small

subset of the data, this averaging can allow information

from other recently seen mini-batches to contribute to

the current parameter update

• A momentum value of 0.9 is often used as a starting

point, but it is common to hand-tune it, the learning

rate, and the schedule used to modify the learning rate

during the training process

a Î[0,1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-46-320.jpg)

![Learning rate schedules

• The learning rate is a critical choice when using

mini-batch based stochastic gradient descent.

• Small values such as 0.001 often work well, but it

is common to perform a logarithmically spaced

search, say in the interval [10-8, 1], followed by a

finer grid or binary search.

• The learning rate may be adapted over epochs t

to give a learning rate schedule, ex.

• A fixed learning rate is often used in the first few

epochs, followed by a decreasing schedule

• Many other options, ex. divide the rate by 10

when the validation error rate ceases to improve

ht =h0 (1+et)-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-47-320.jpg)

![Parameter initialization

• Can be deceptively important!

• Bias terms are often initialized to 0 with no issues

• Weight matrices more problematic, ex.

– If initialized to all 0s, can be shown that the tanh activation

function will yield zero gradients

– If the weights are all the same, hidden units will produce same

gradients and behave the same as each other (wasting params)

• One solution: initialize all elements of weight matrix from

uniform distribution over interval [–b, b]

• Different methods have been proposed for selecting the

value of b, often motivated by the idea that units with

more inputs should have smaller weights

• Weight matrices of rectified linear units have been

successfully initialized using a zero-mean isotropic Gaussian

distribution with standard deviation of 0.01](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-51-320.jpg)

![Correlation and convolution

• Suppose our filter is centered, giving the first vector

element an index of –1, or an index of –K, where K is the

“radius” of the filter, then 1D filtering can be written

• Directly generalizing this filtering to a 2D image X and

filter W gives the cross-correlation, Y=WX, for which

the result for row r and column c is

• The convolution of an image with a filter, Y=W*X , is

obtained by simply flipping the sense of the filter

y[n]= w[k]x[n+k]

k=-K

K

å

Y[r,c]= W[ j,k]X[r + j,c+k]

k=-K

K

å

j=-J

J

å

Y[r,c]= W[-j,-k]X[r + j,c+k]

k=-K

K

å

j=-J

J

å](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-64-320.jpg)

![Convolutional layers and gradients

• Let’s consider how to compute the gradients

needed to optimize a convolutional network

• At a given layer we have i=1…N(l) feature filters

and corresponding feature maps

• The convolutional kernel matrices Ki contain

flipped weights with respect to kernel weight

matrices Wi

• With activation function act(), and for each

feature type i, a scaling factor gi and bias matrix

Bi, the feature maps are matrices Hi(Ai(X)) and

can be visualized as a set of images given by

Hi = gi act Ki *X+Bi

[ ]= gi act Ai (X)

[ ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-68-320.jpg)

![Convolutional layers and gradients

• The loss is a function of the N(l) feature maps for

a given layer,

• Define h=vec(H), x=vec(X), a=vec(A), where the

vec() function returns a vector with stacked

columns of the given matrix argument,

• Choose an act() function that operates

elementwise on an input matrix of pre-

activations and has scale parameters of 1 and

biases of 0.

• Partial derivatives of hidden layer output with

respect to input X of the convolutional units are

L = L(H1

(l)

,… ,HN(l)

(l)

)

¶L

¶X

=

¶aijk

¶X

¶Hi

¶aijk

k

å

j

å

i

å

¶L

¶Hi

=

¶ai

¶x

¶hi

¶ai

¶L

¶hi

i

å = Wi *Di

[ ]

i

å ,Di = dL ¶Ai](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter10-231015053758-df62baf8/85/Chapter10-pptx-69-320.jpg)