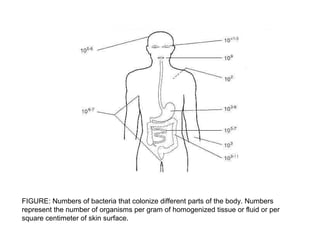

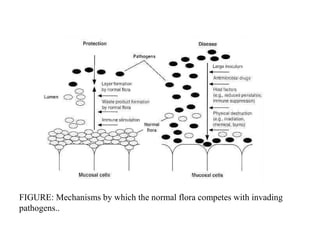

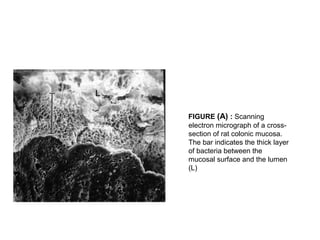

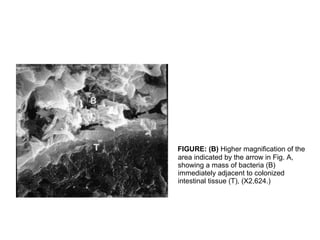

The document discusses the normal microbial flora that inhabit healthy humans. It describes how the skin, mouth, intestines and other areas each have distinct resident and transient bacterial populations that protect against pathogens. The resident flora establishes itself and repopulates if disturbed, while the transient flora does not permanently colonize. These normal flora provide colonization resistance against infection and have important nutritional and protective functions. Figures show bacterial numbers by body site and mechanisms of pathogen competition.