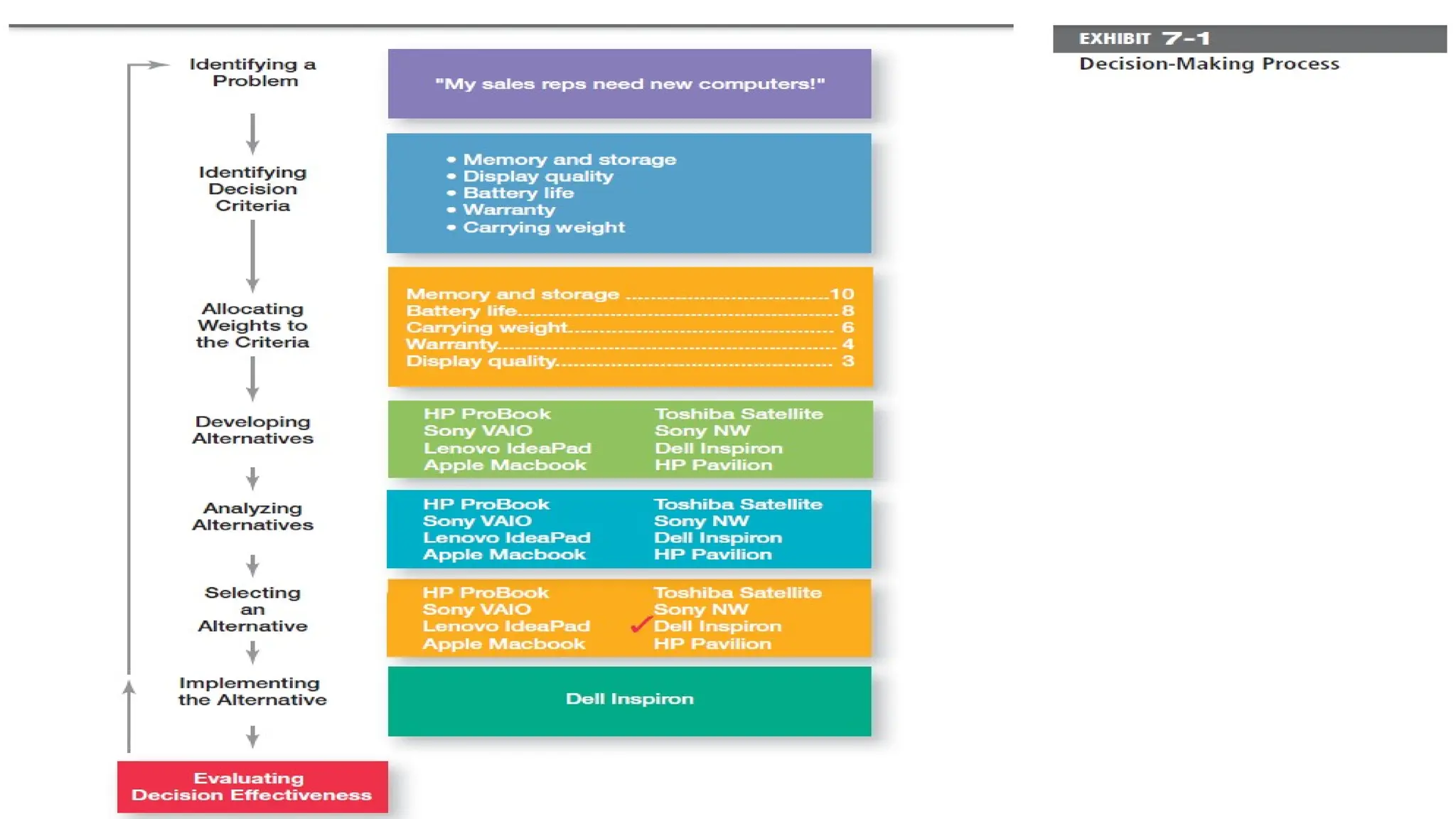

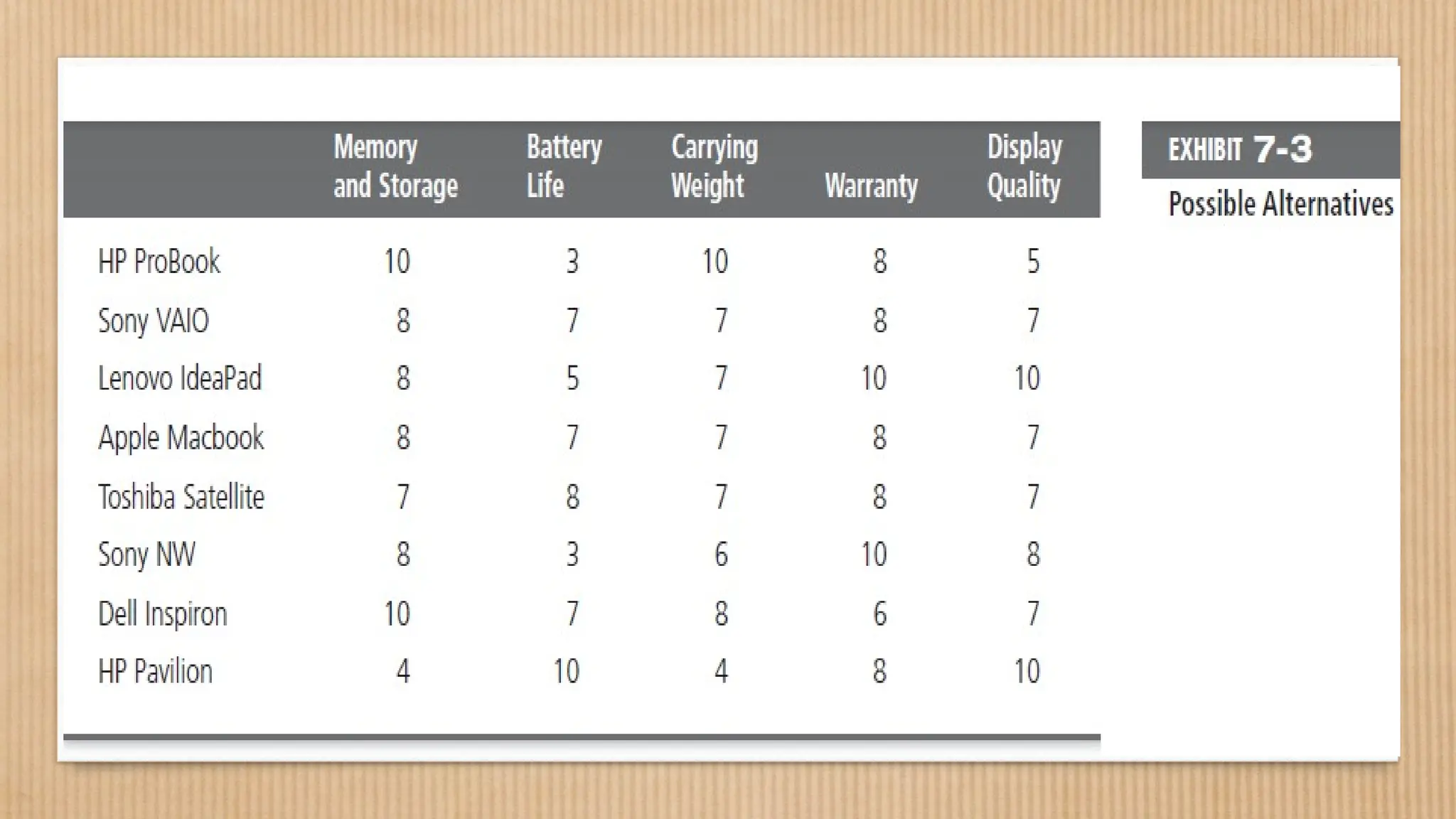

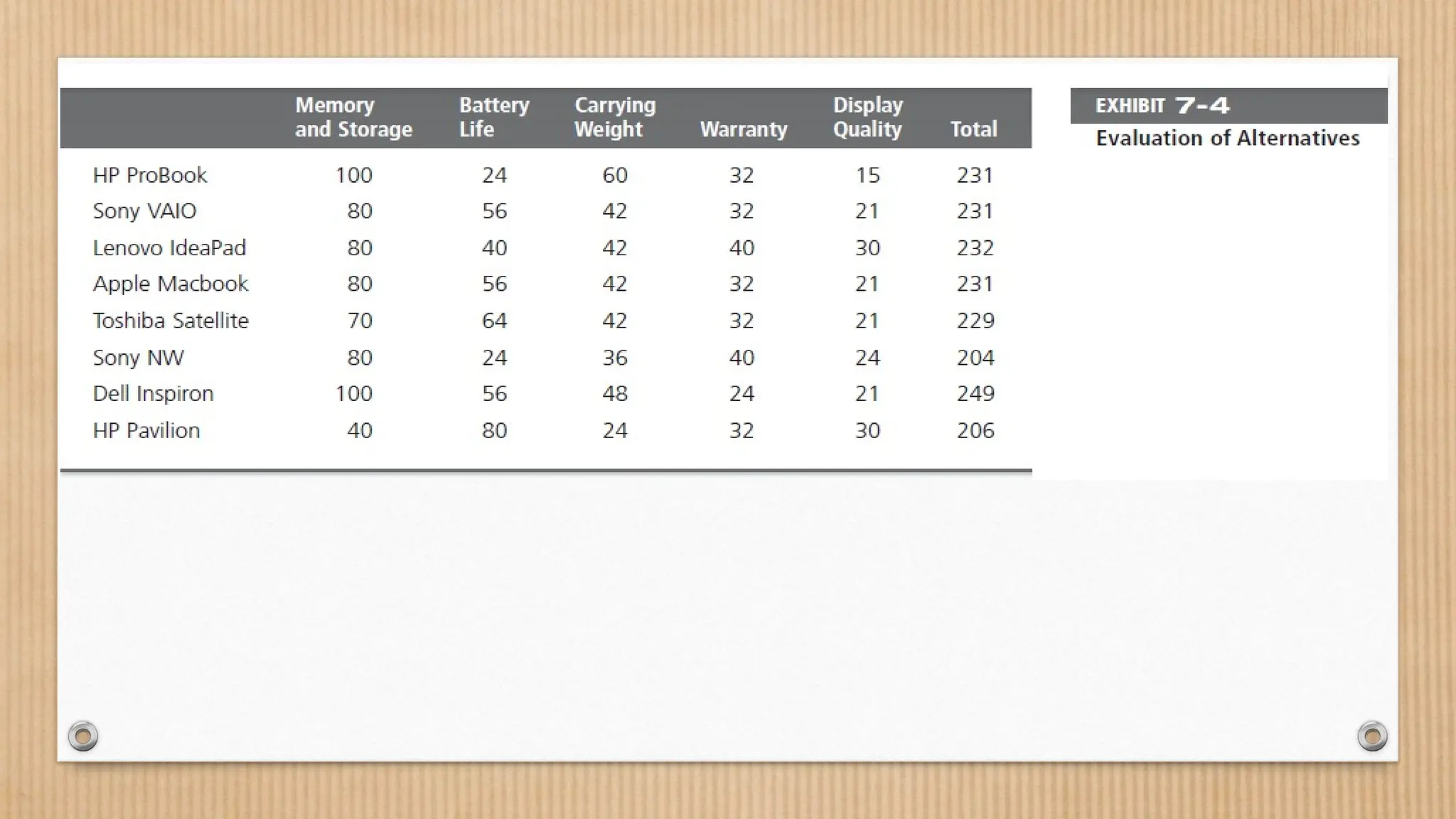

Chapter 7 discusses the decision-making process for managers at all organizational levels, highlighting eight steps: identifying a problem, criteria, weighting, developing alternatives, analyzing alternatives, selecting an alternative, implementing the decision, and evaluating its effectiveness. Managers must navigate these steps to resolve issues ranging from production schedules to organizational goals. It emphasizes the importance of thorough evaluation and flexibility in response to changing conditions.