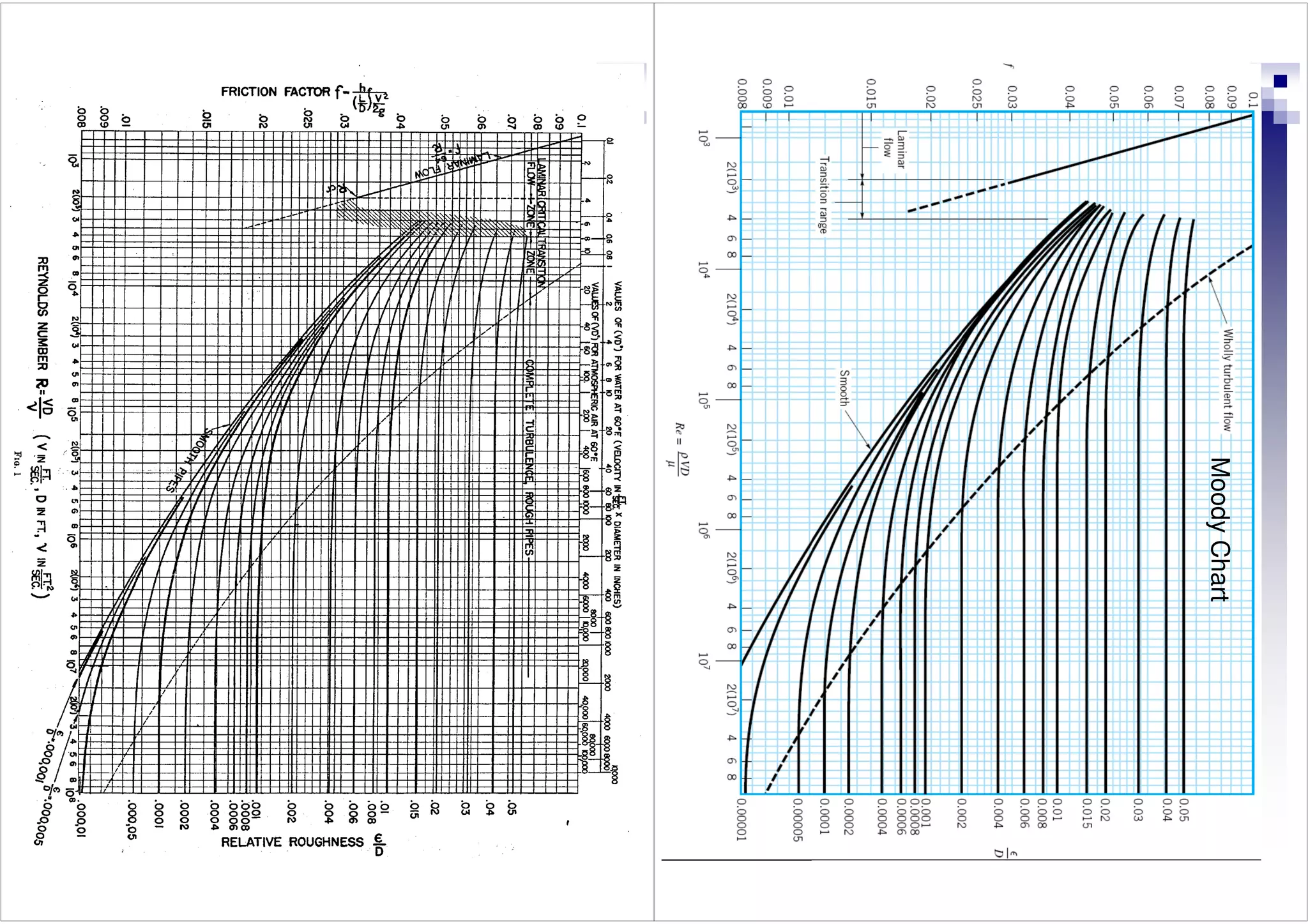

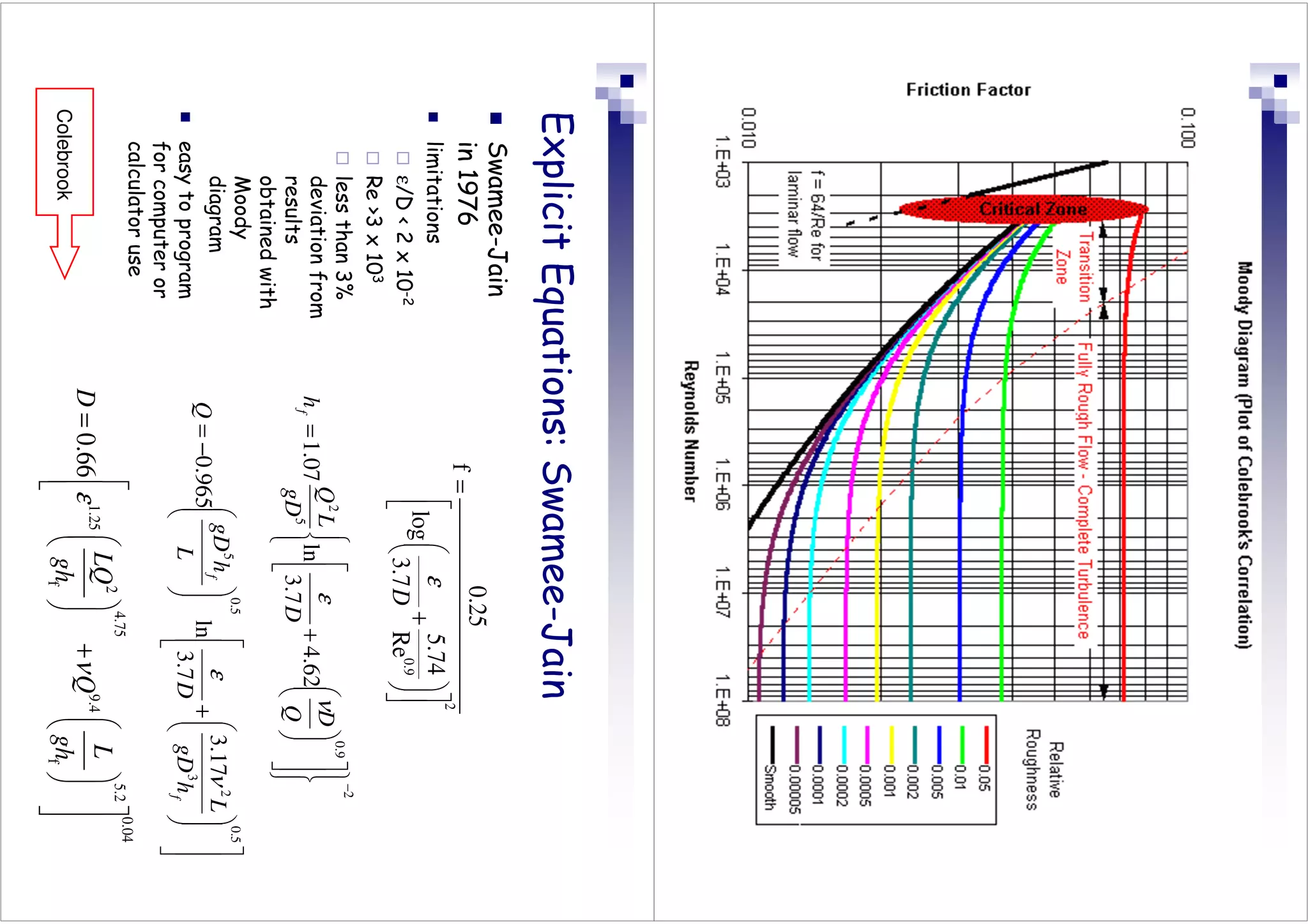

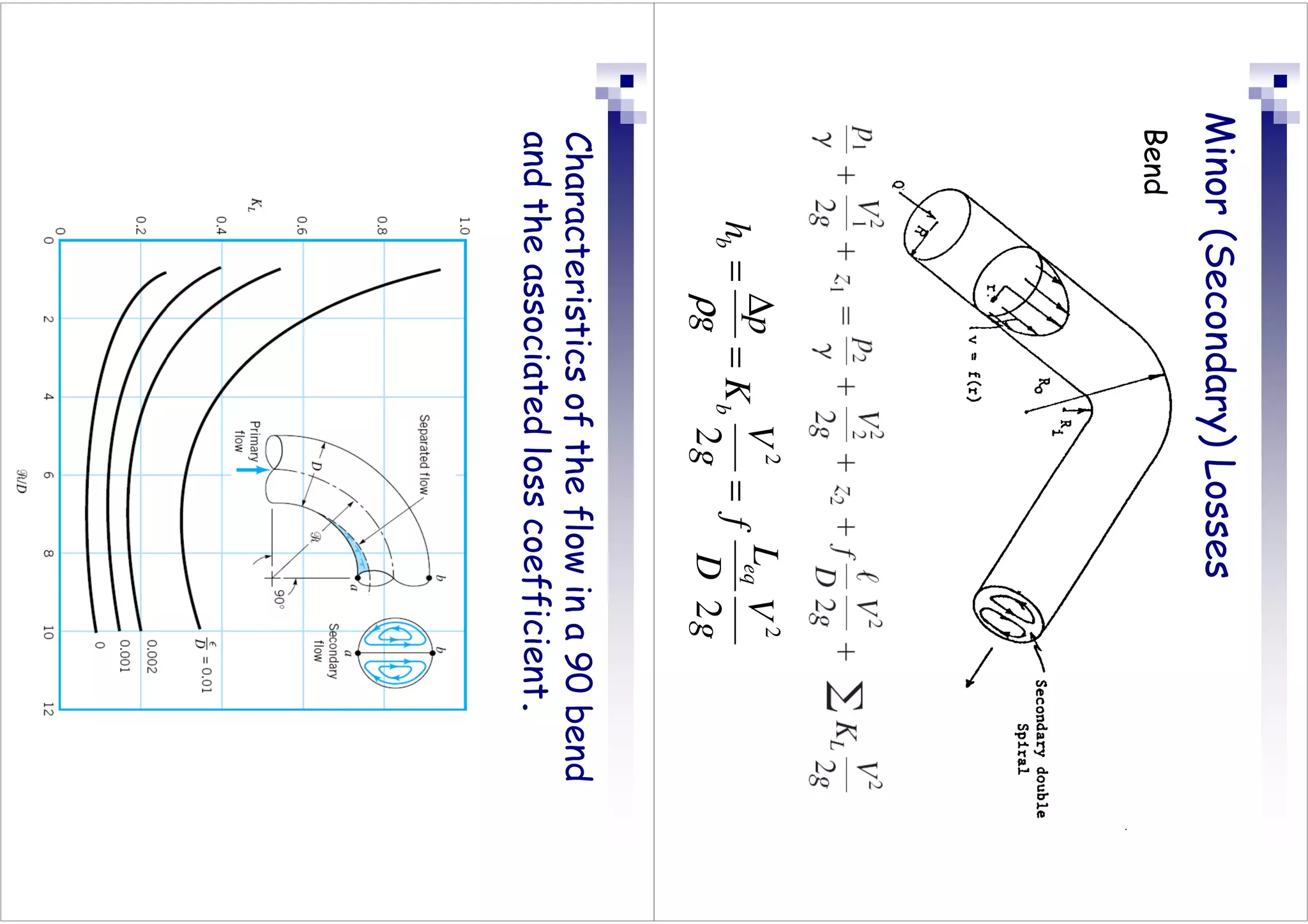

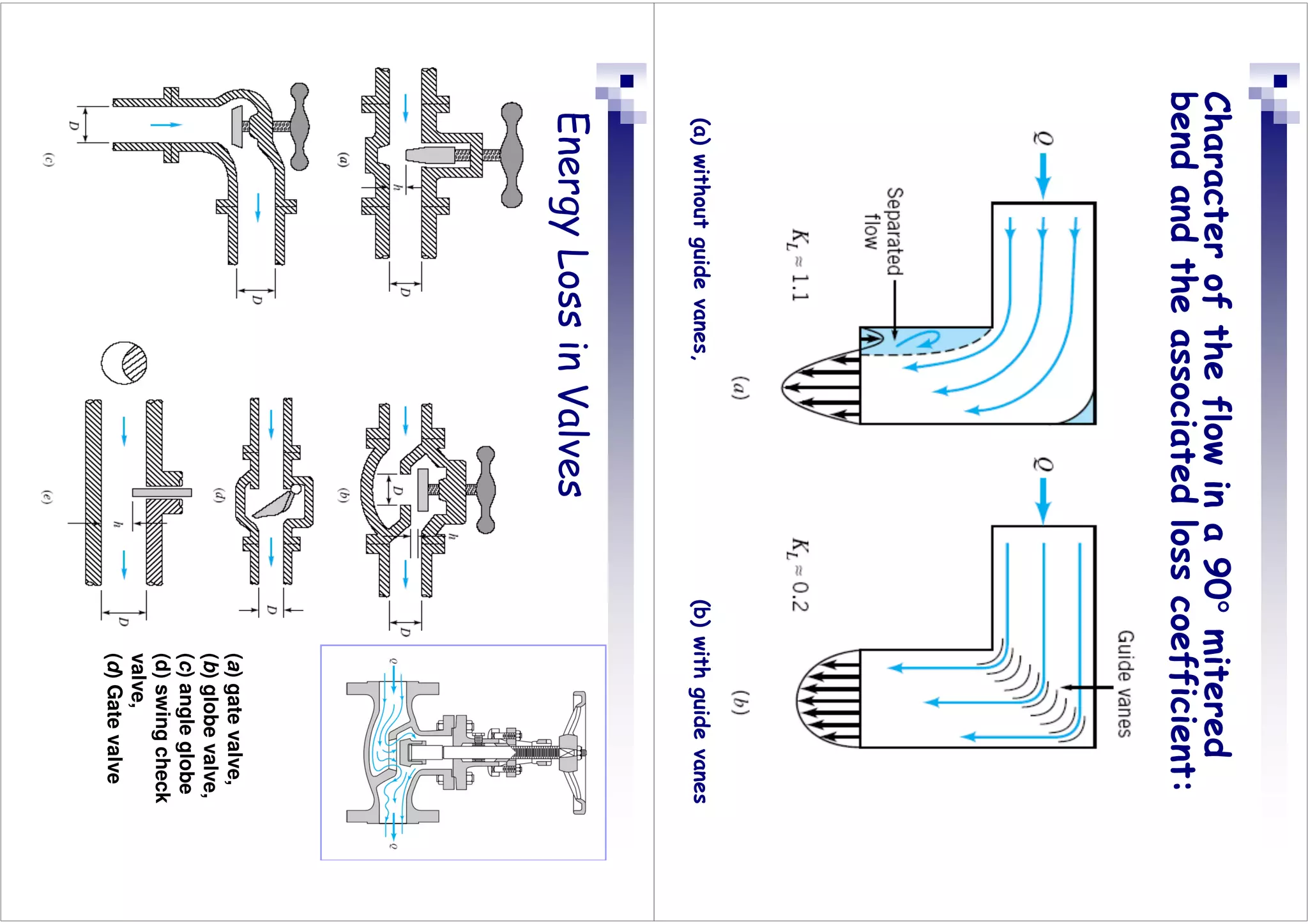

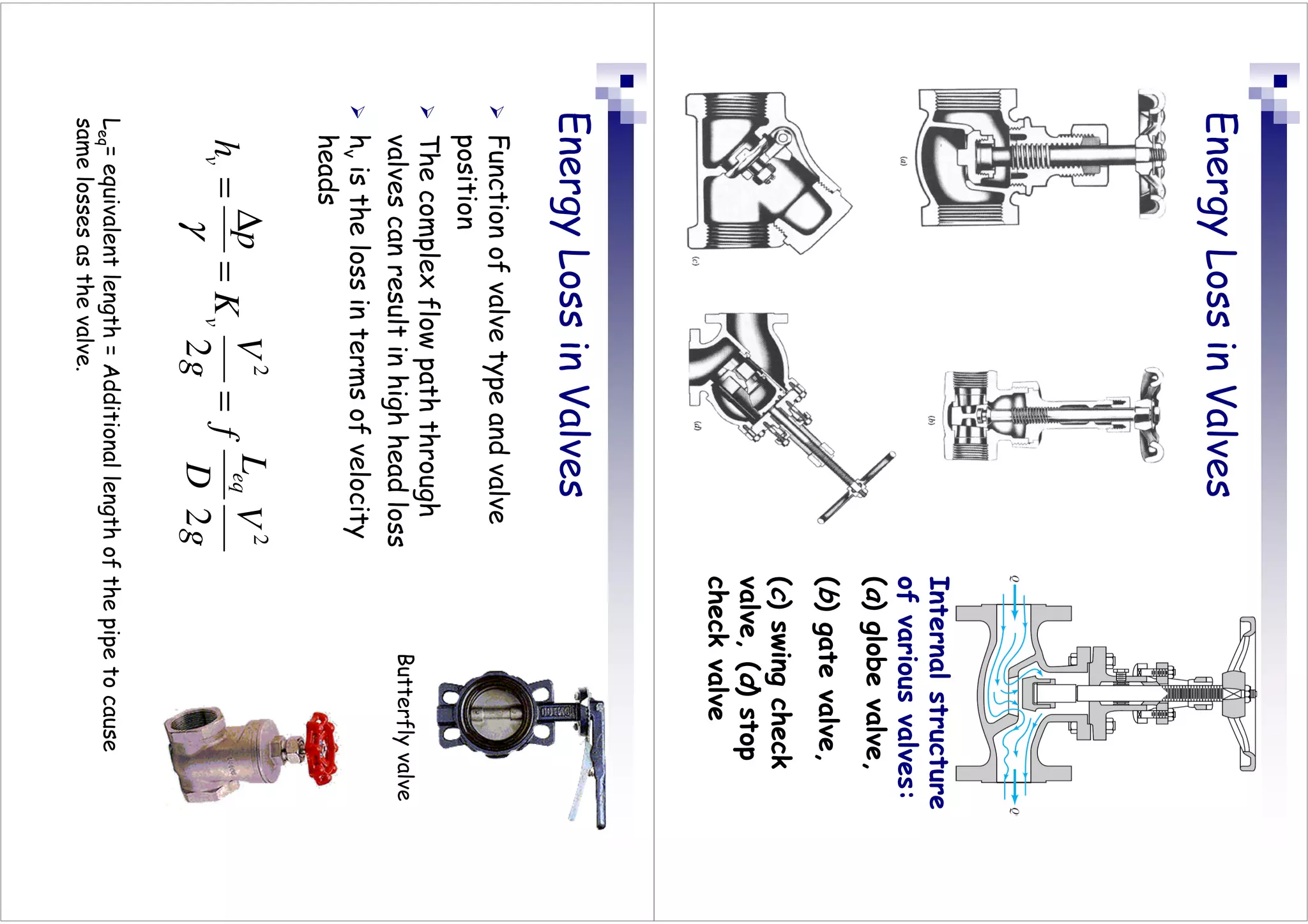

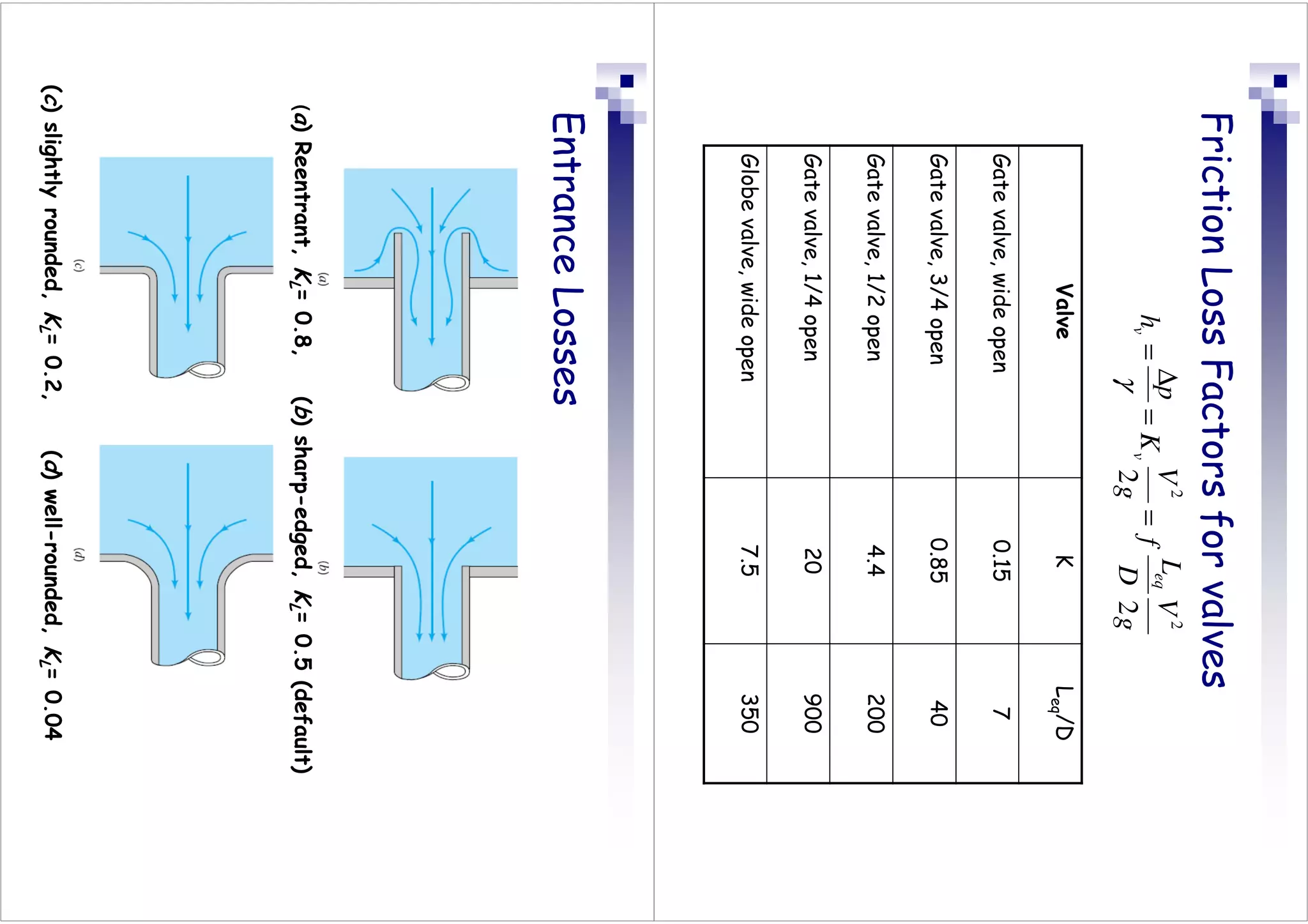

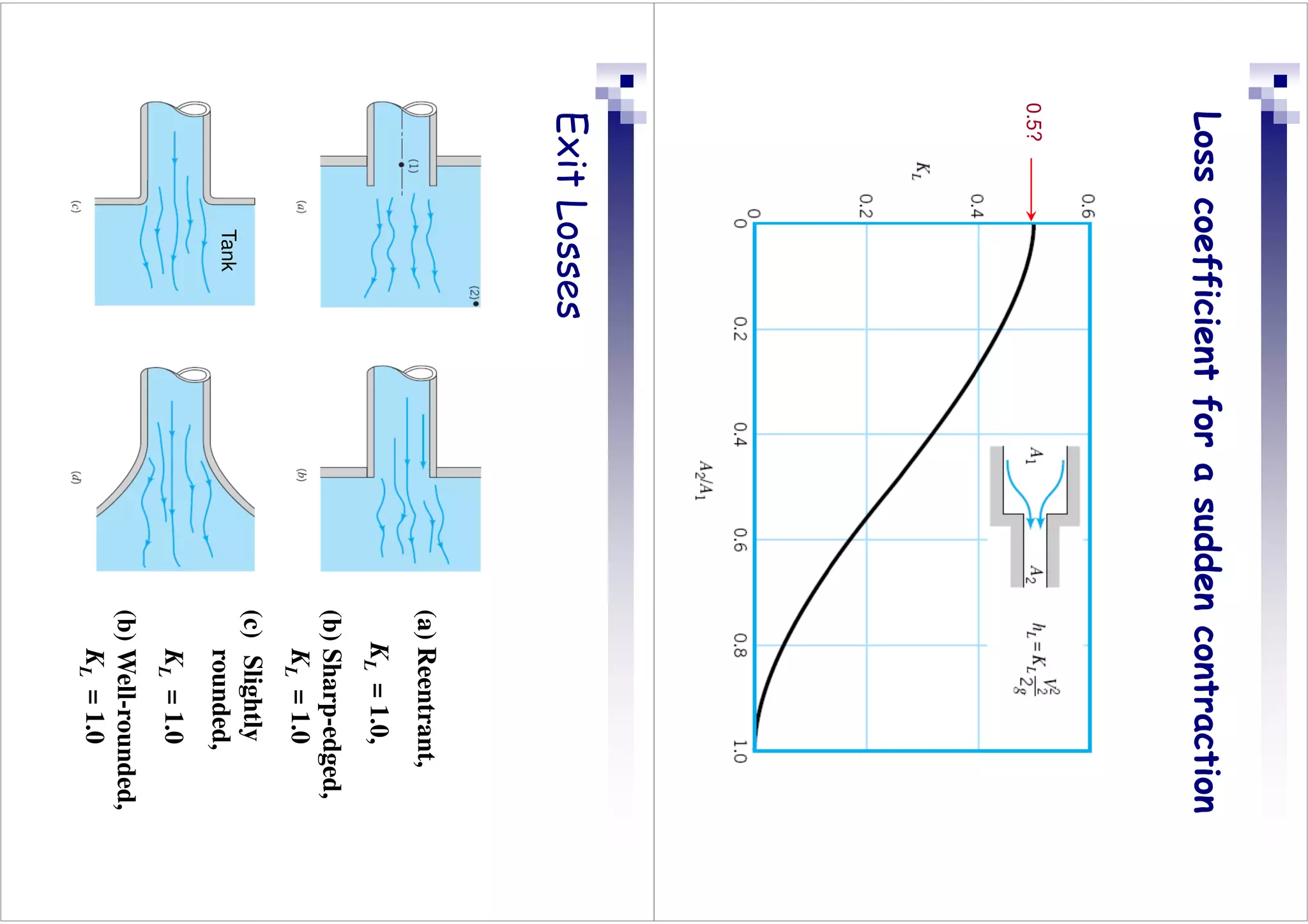

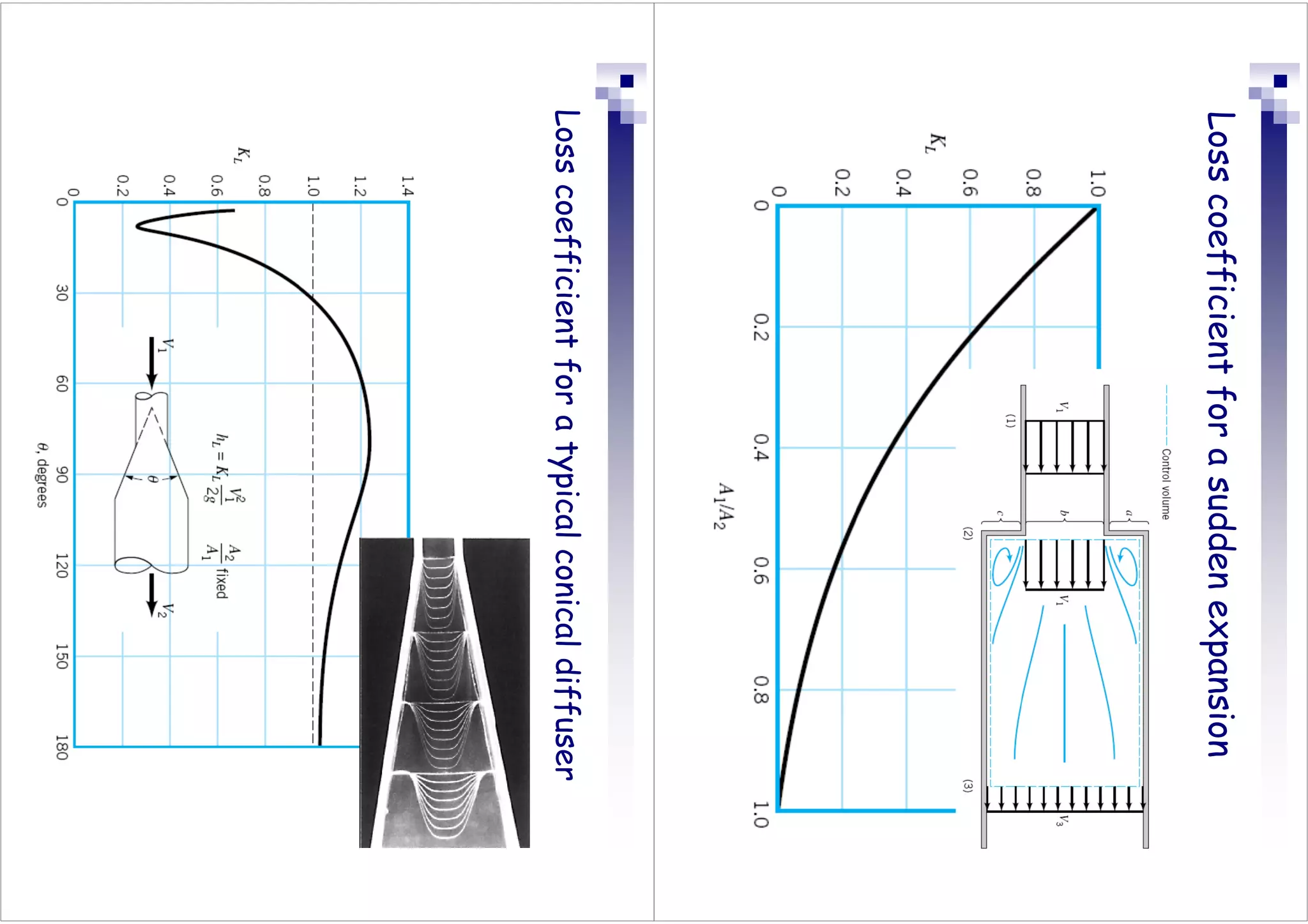

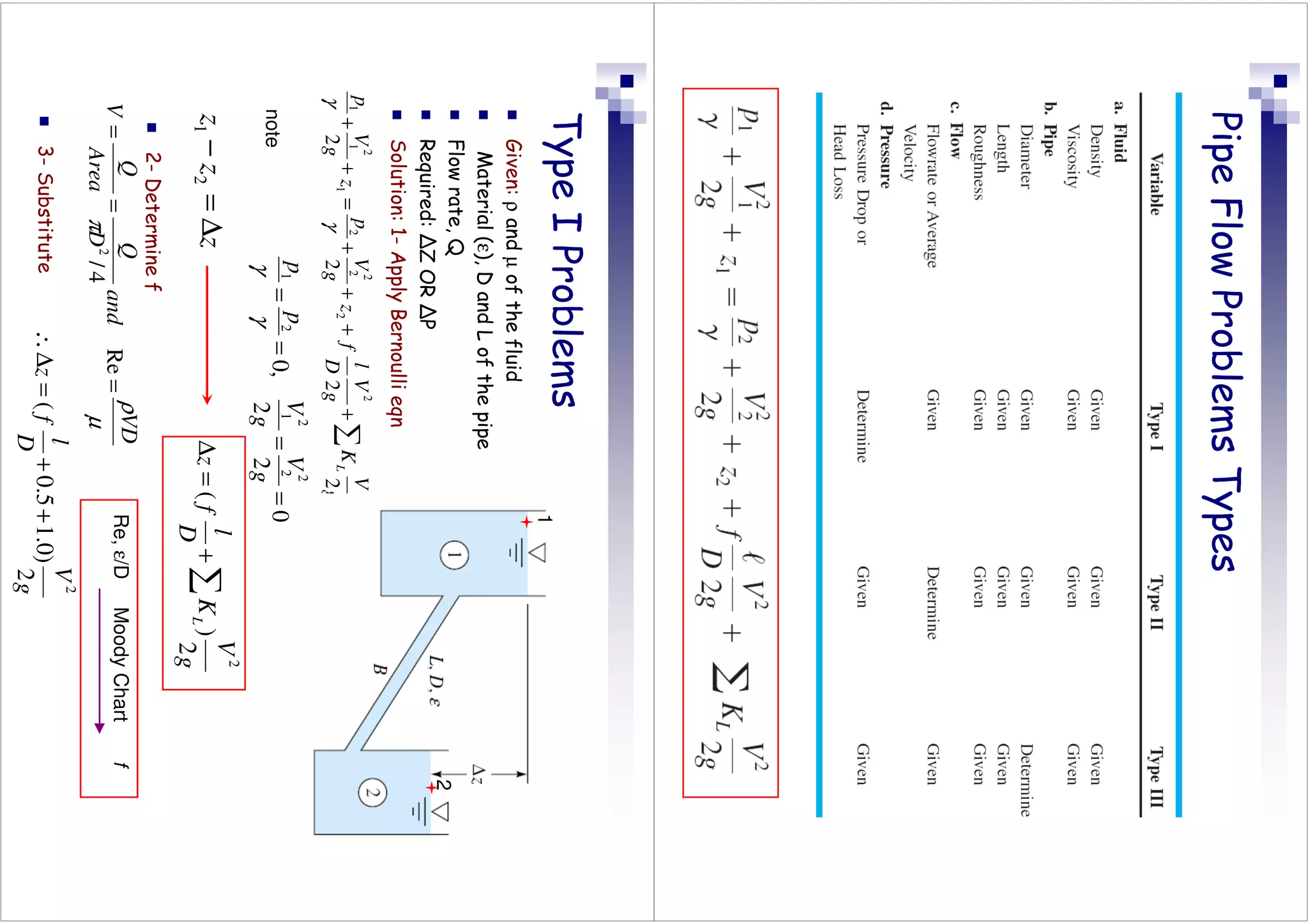

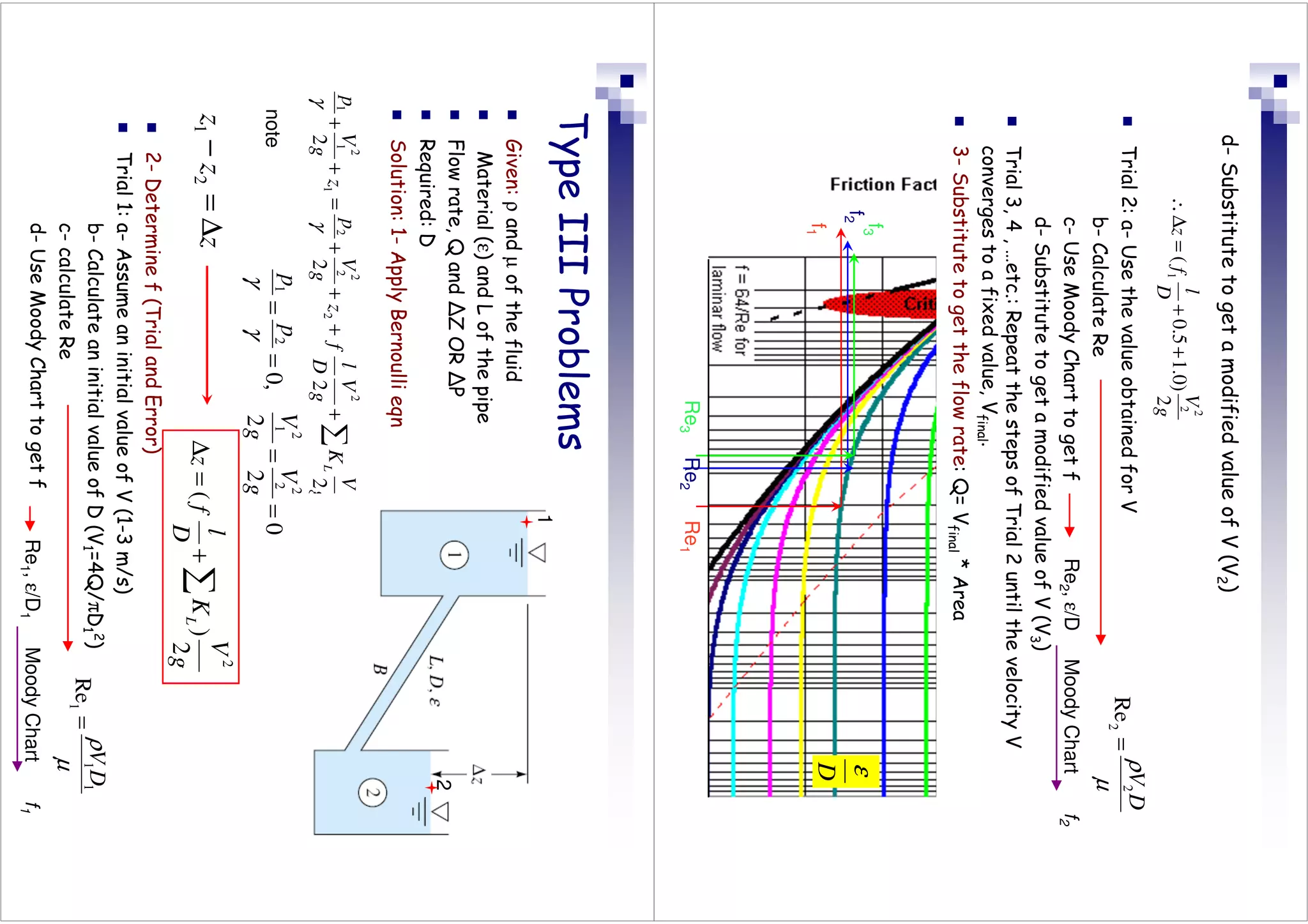

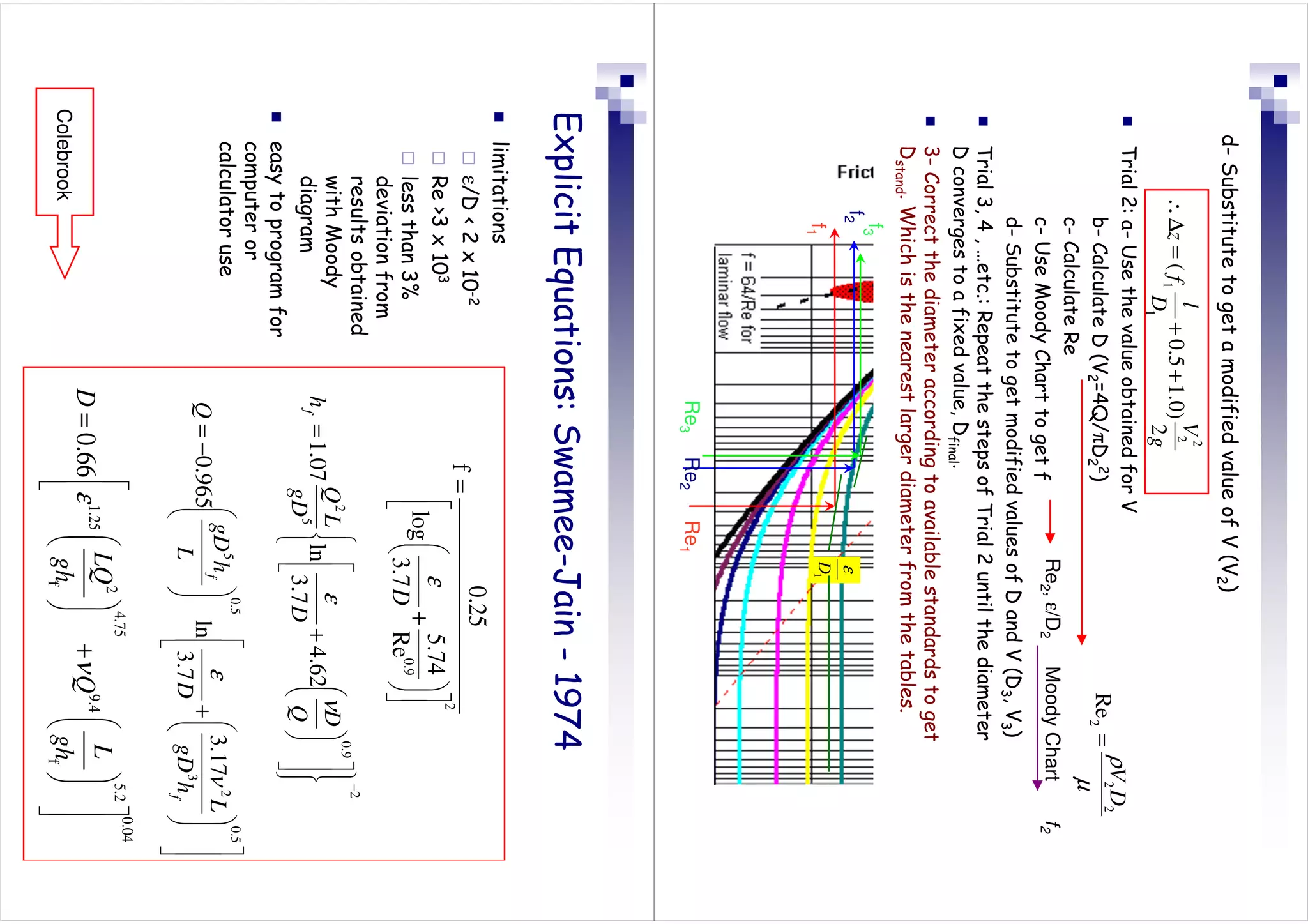

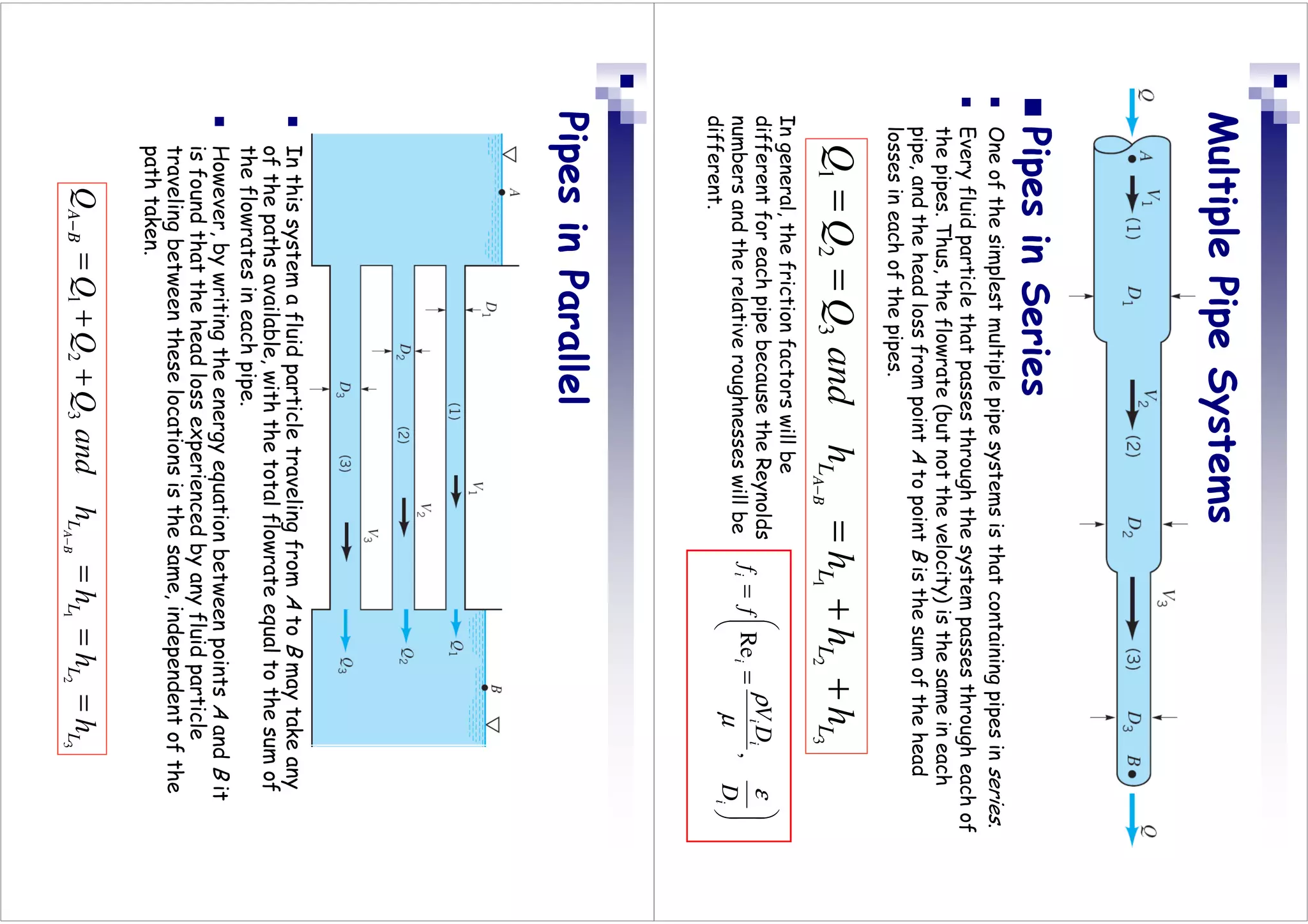

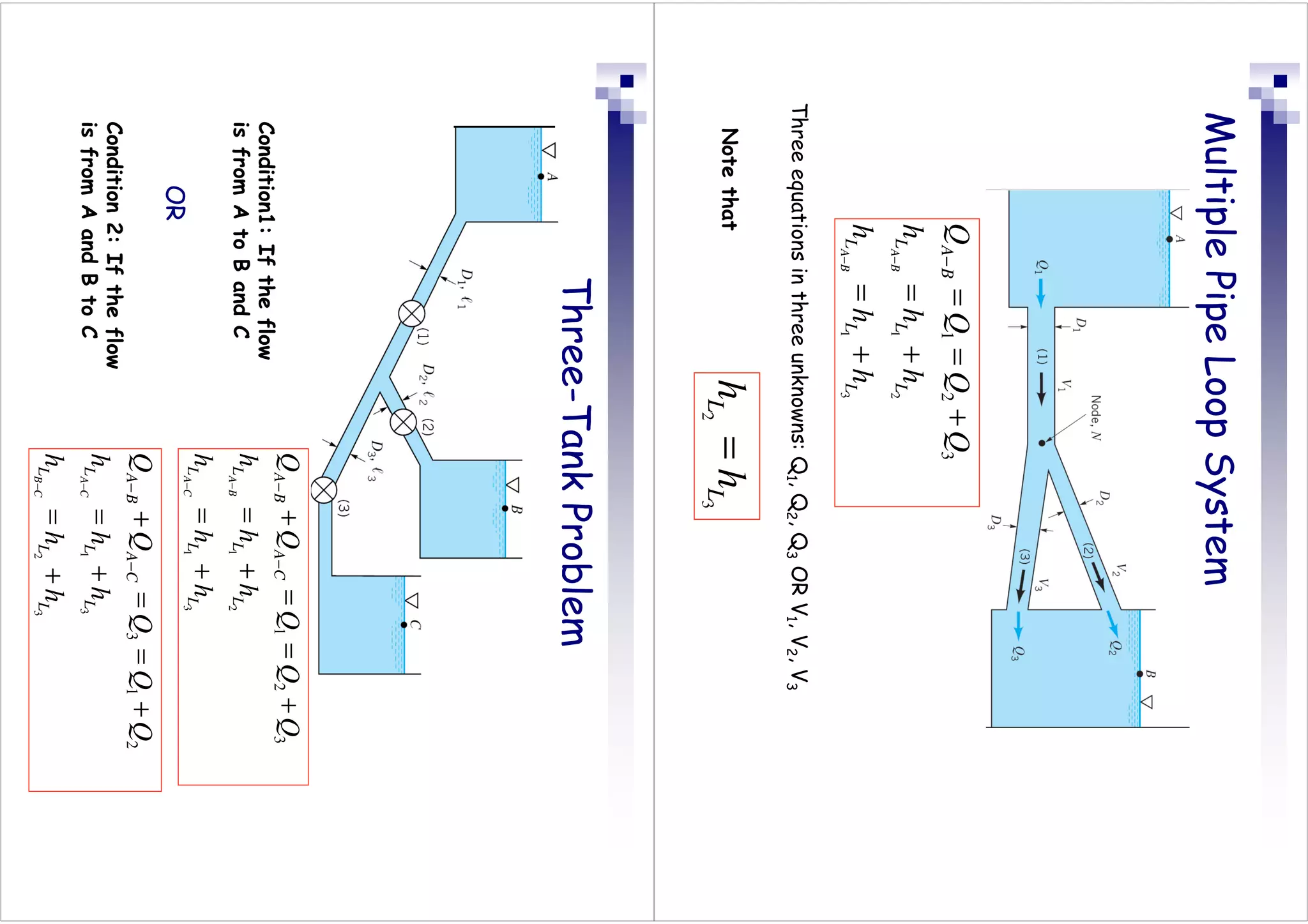

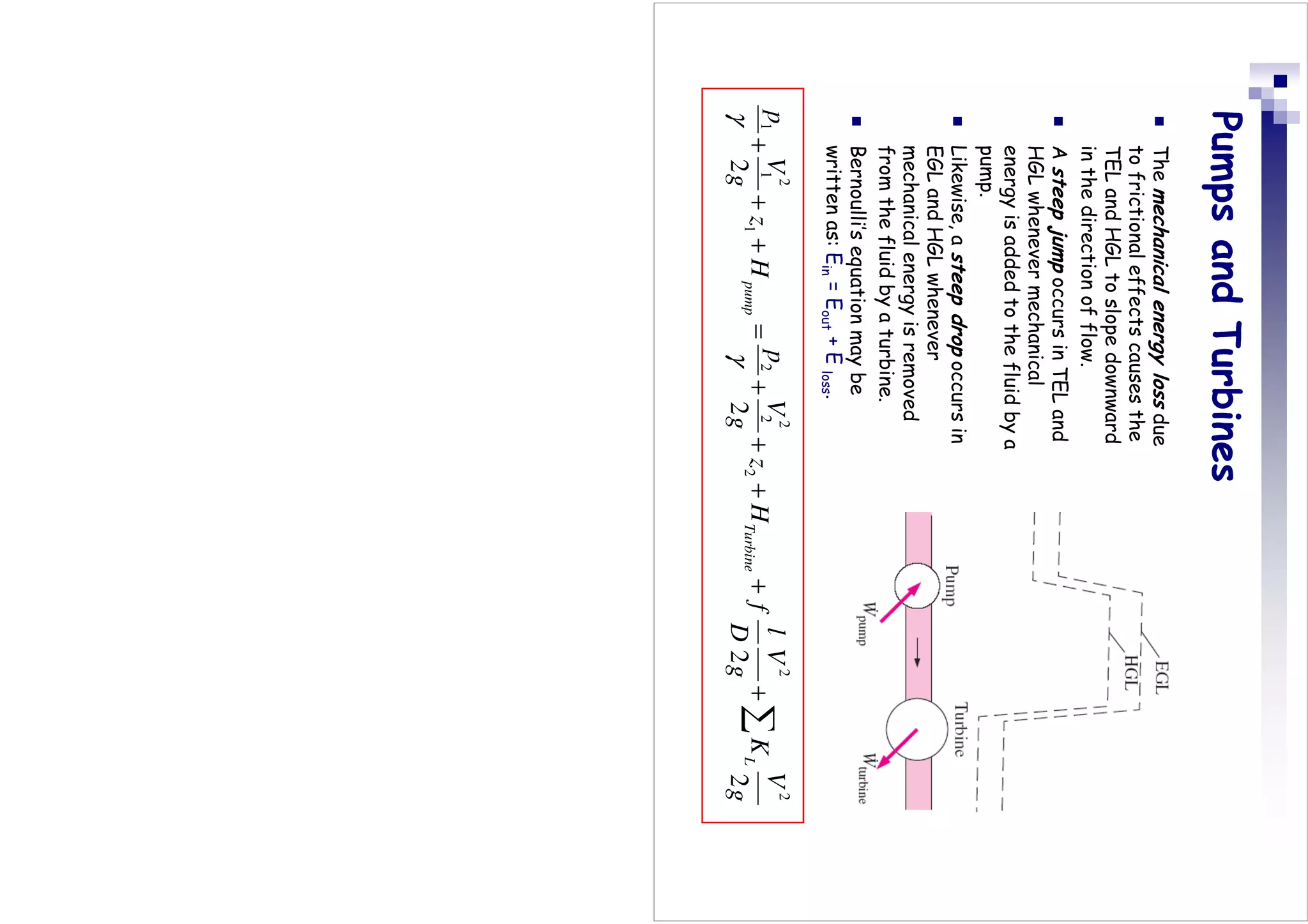

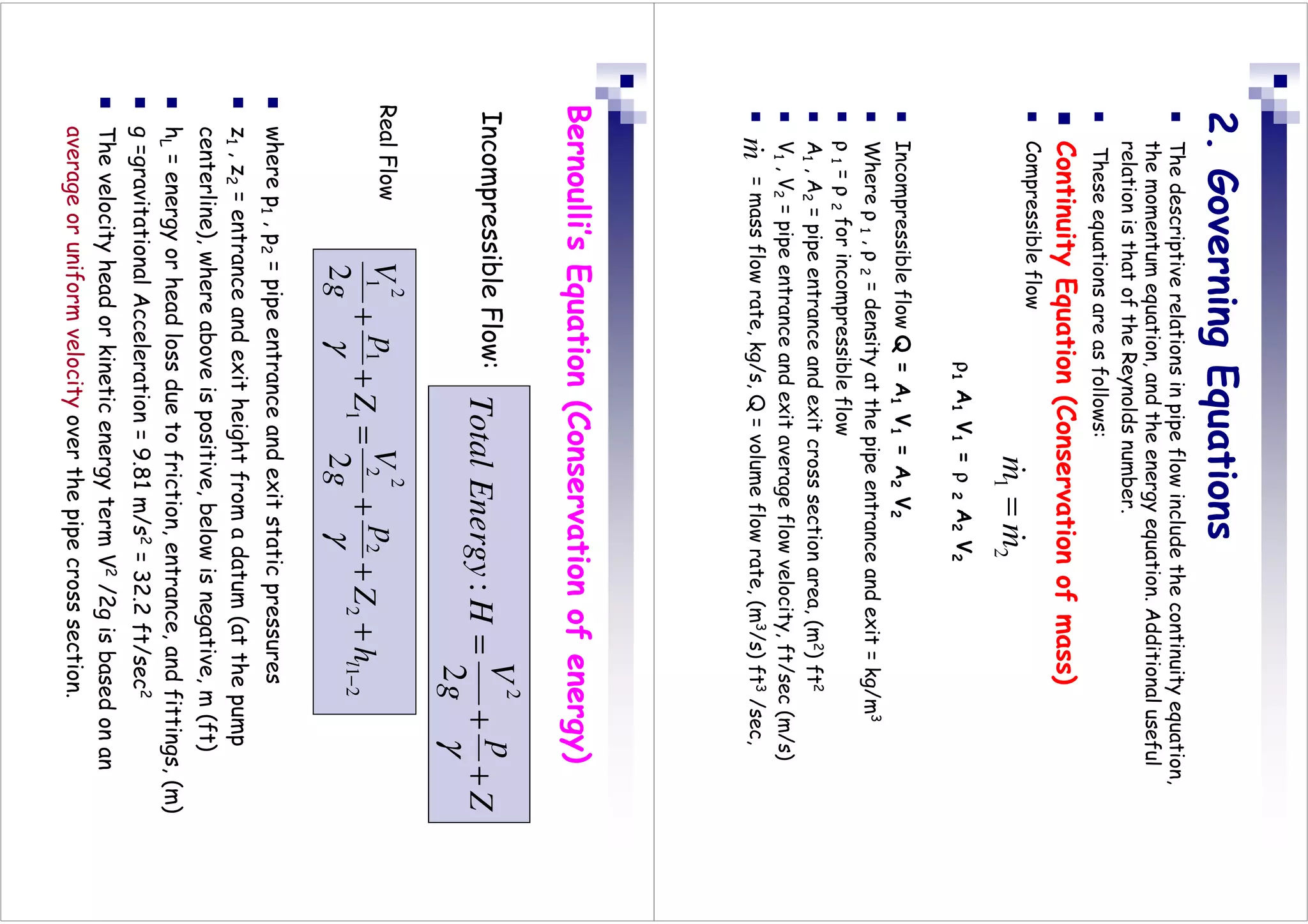

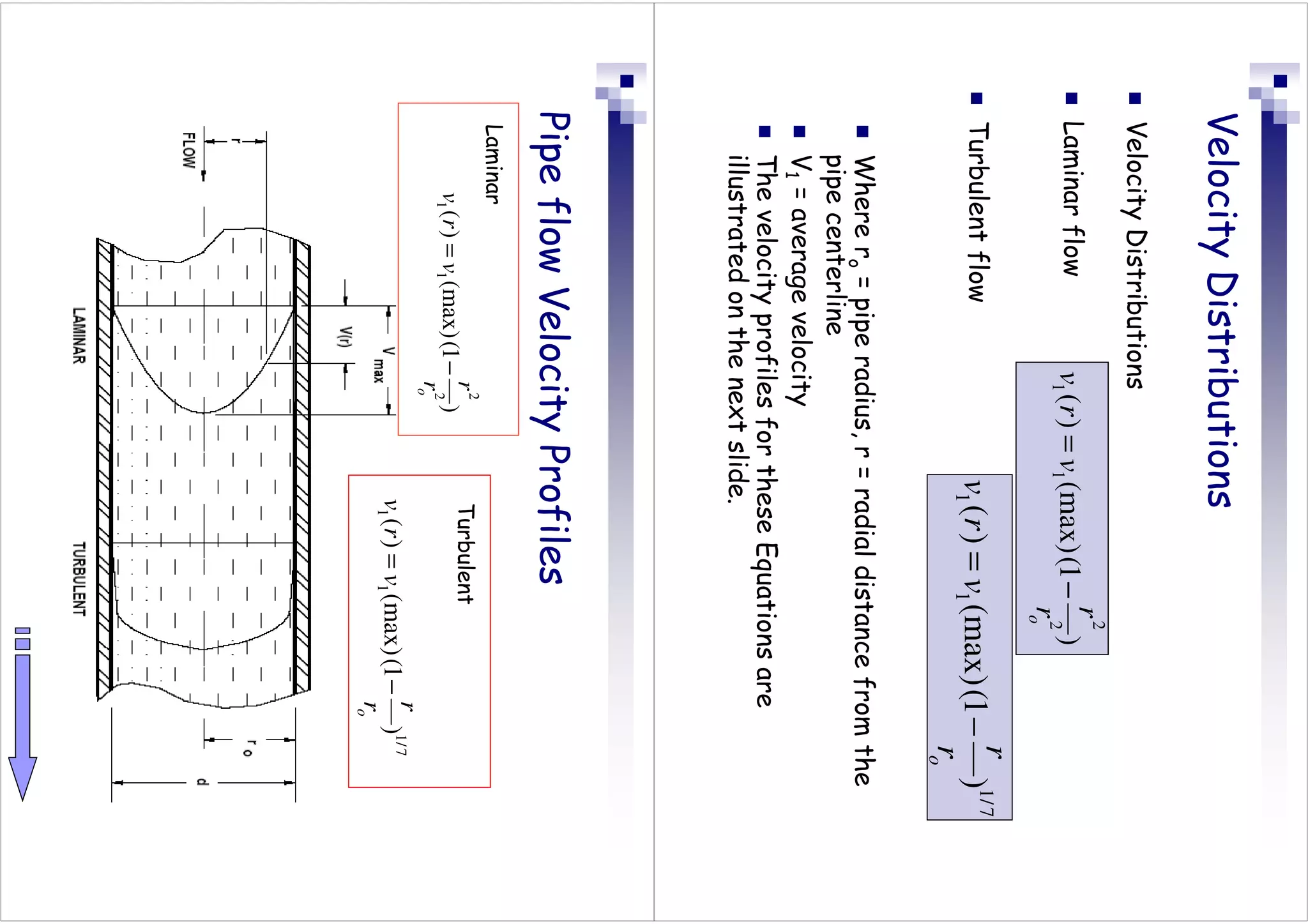

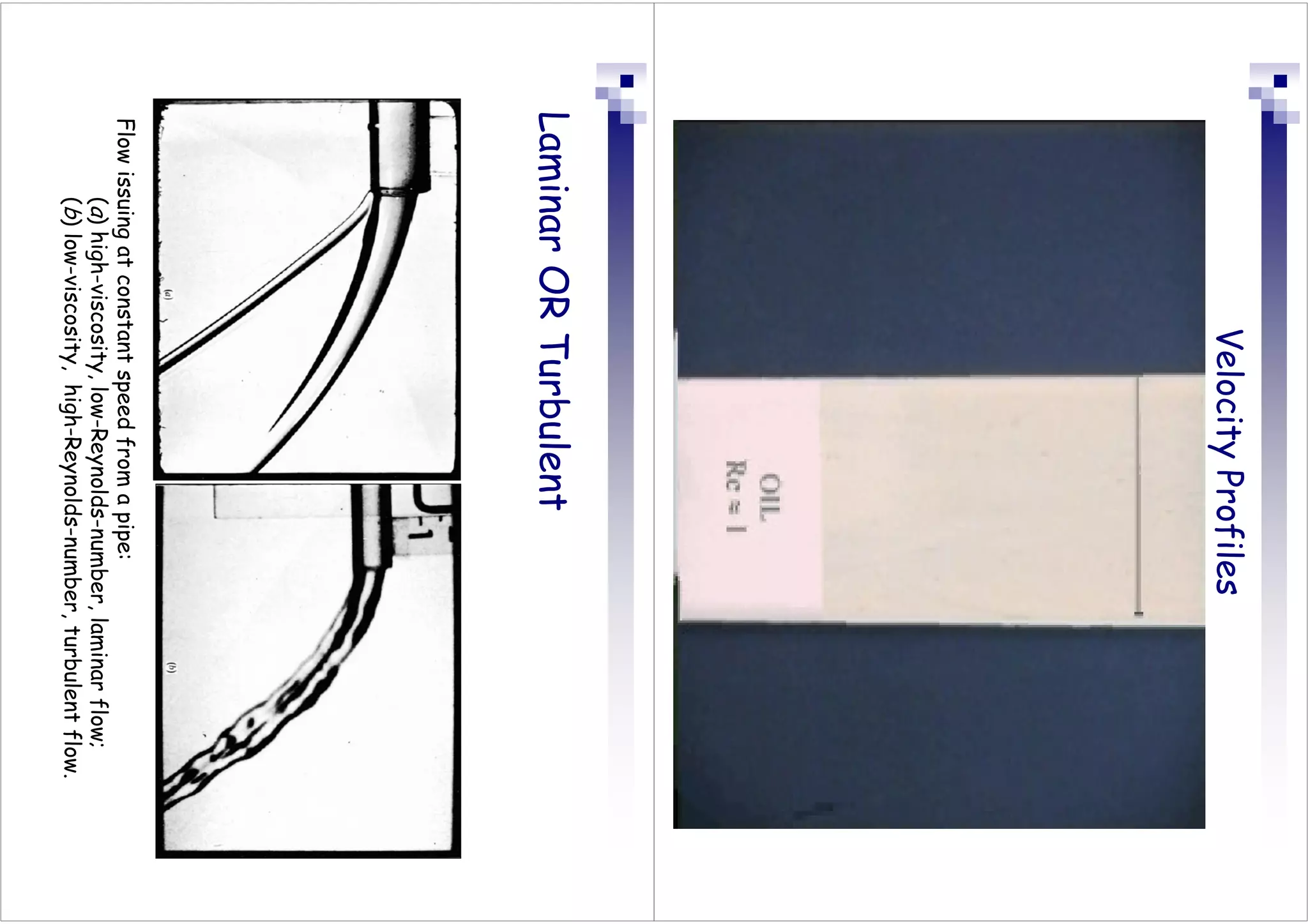

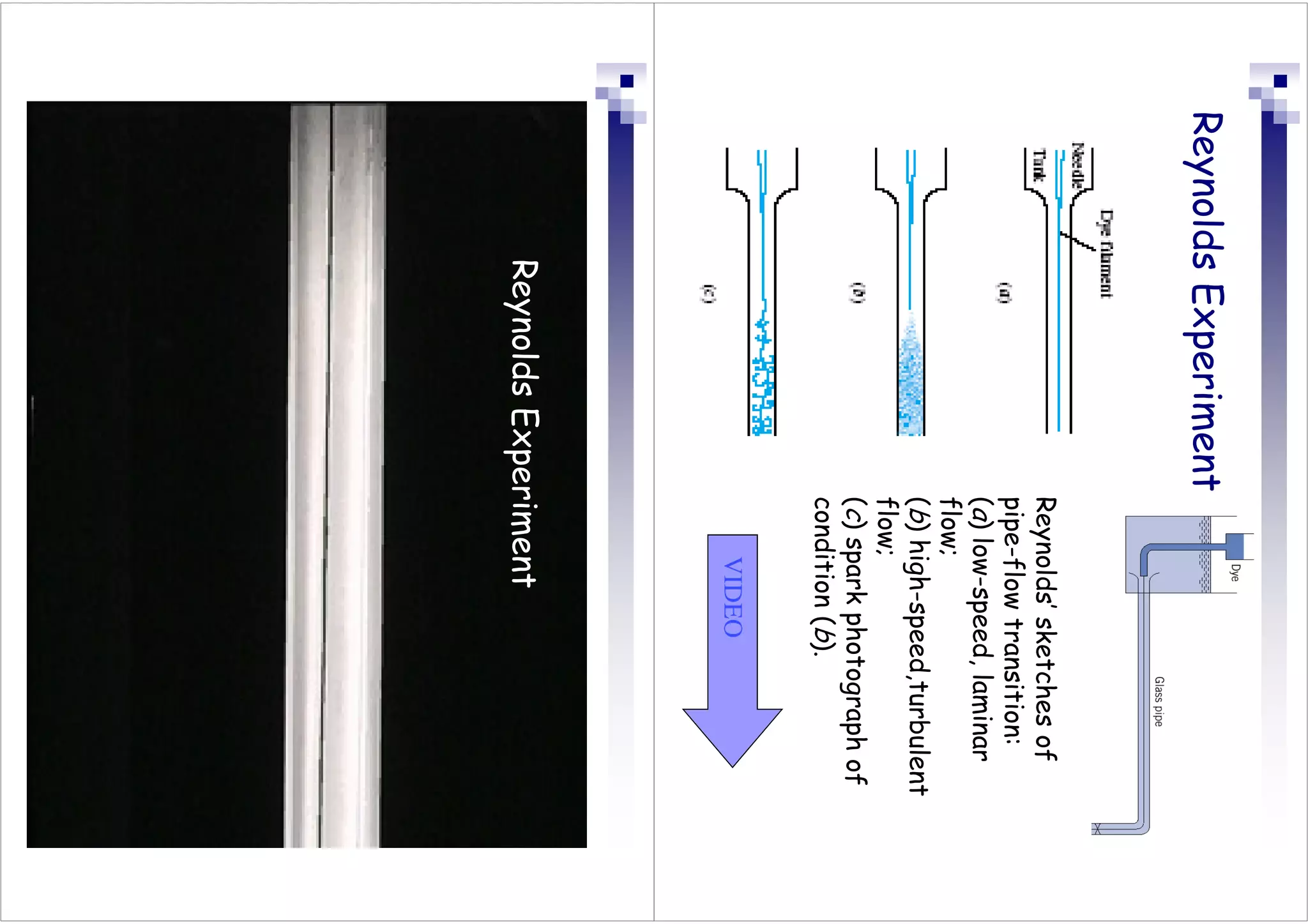

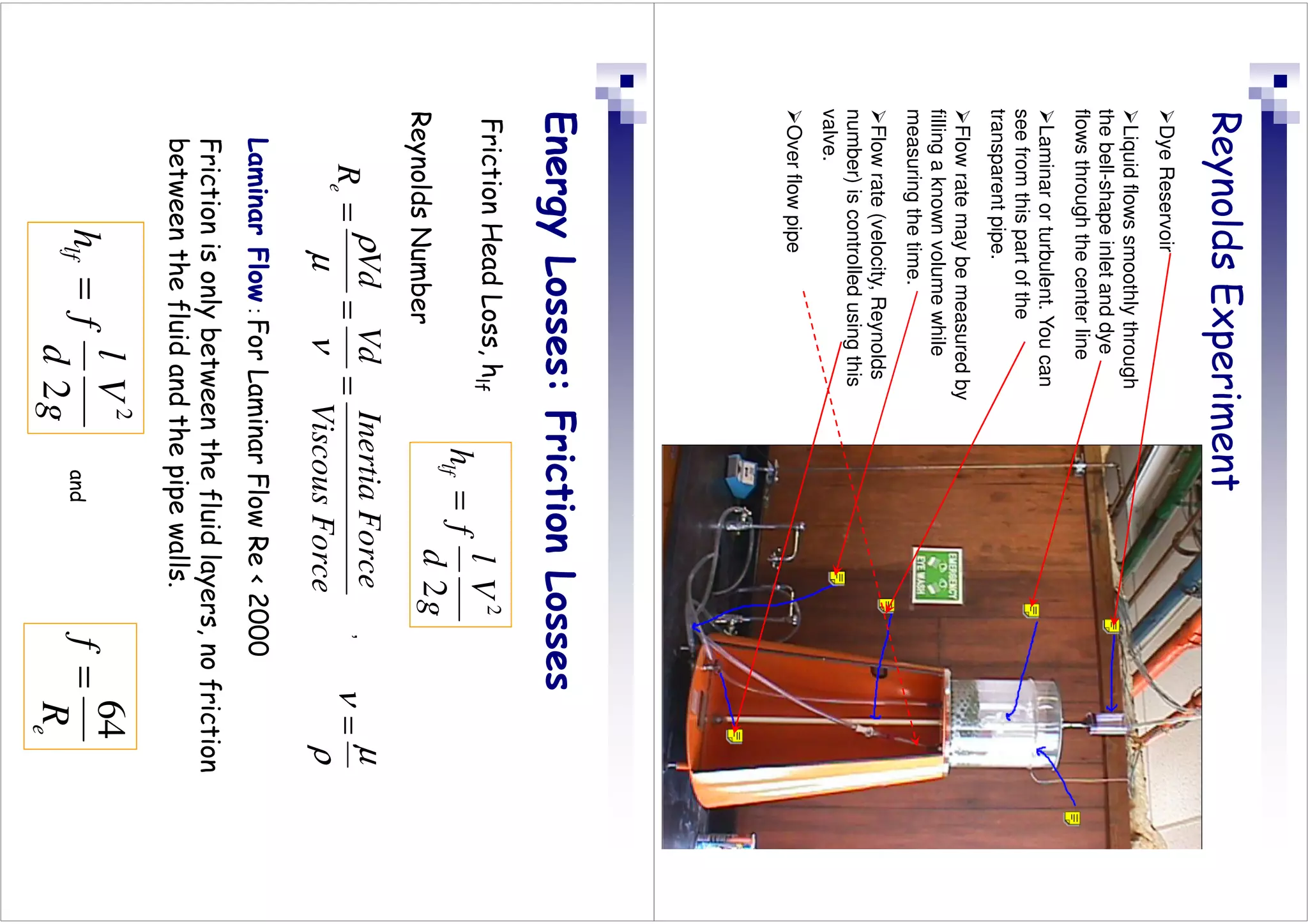

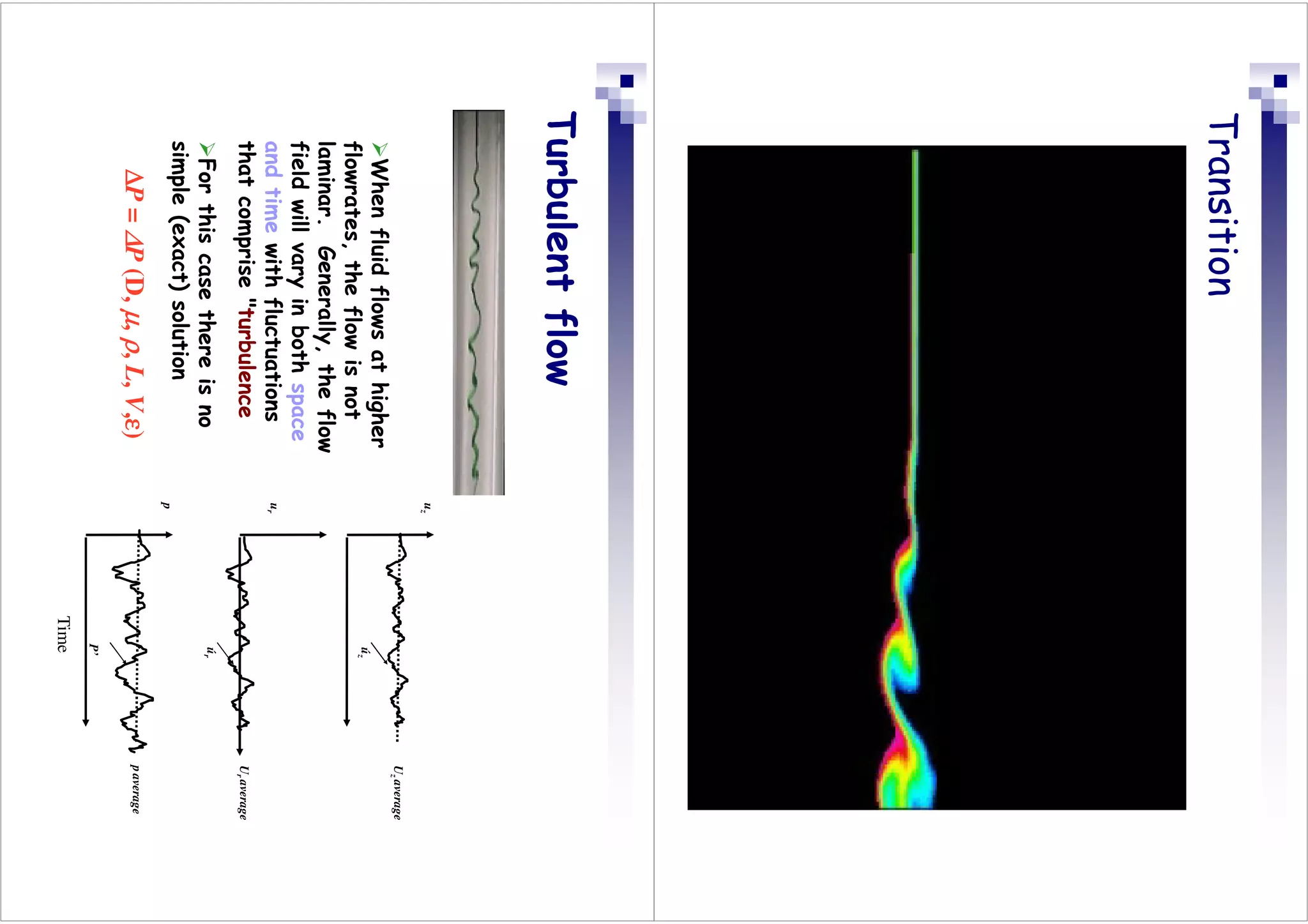

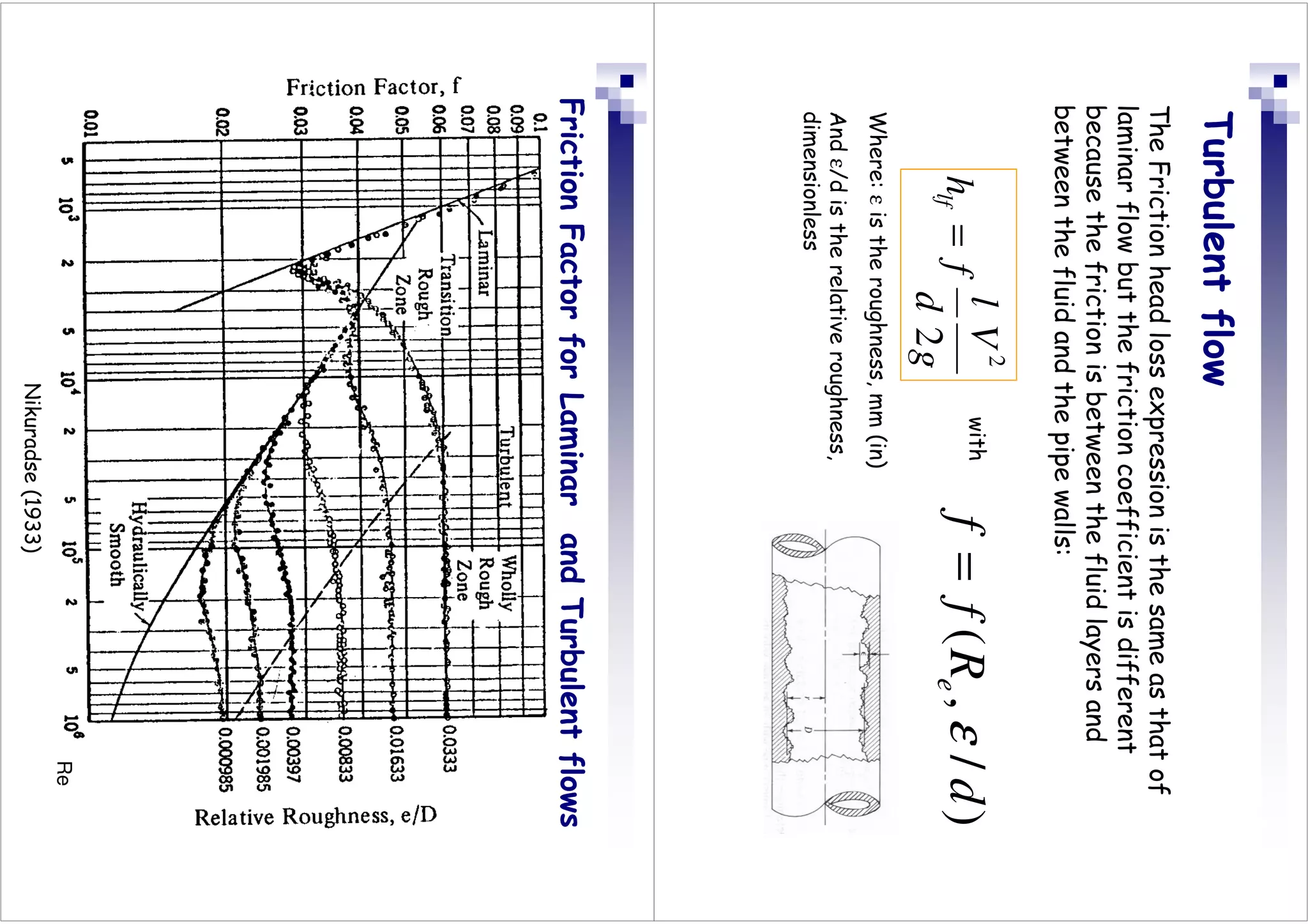

This document discusses flow in pipes. It covers different types of pipe flow including steady/unsteady and laminar/turbulent. The governing equations for pipe flow are presented, including continuity, momentum, and energy equations. Velocity profiles for laminar and turbulent flow are shown. Common pipe flow problems involve specifying a flowrate and calculating the required pressure difference to overcome friction losses.

![[

]

8

0

Re

log

0

2

1

.

*

*

.

−

=

f

f

a-Smooth

pipe,

Re4000

f

≠

f

(ε/d)

14

.

1

log

0

2

1

+

−

=

D

f

ε

*

.

b-

Rough

pipe,

[

(D/ε)/(Re√ƒ)

0.01],

f

≠

f

(Re)

)

Re

51

.

2

7

.

3

/

log(

0

2

1

f

D

f

+

−

=

ε

*

.

c

-Transition

function

for

both

smooth

and

rough

pipe

(Colebrook)

25

.

0

Re

316

.

0

−

=

f

g

V

d

l

f

h

lf

2

2

=

Empirical

Correlations

Friction

Factor

for

Turbulent

flow

Values

of

Equivalent

Roughness

(new

pipes)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-230218180852-20a79c05/75/Ch-8-Flow-in-pipes-pdf-9-2048.jpg)