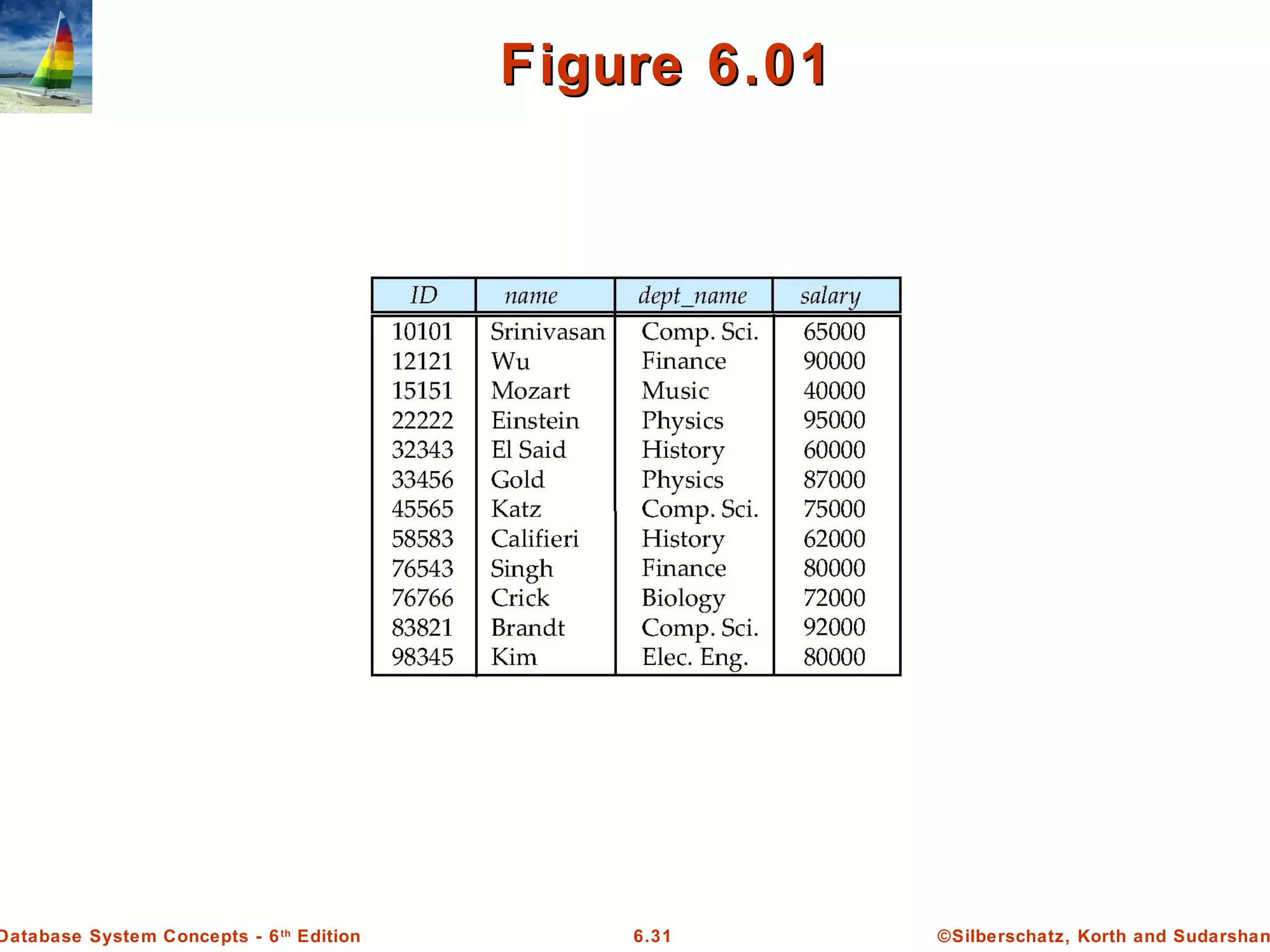

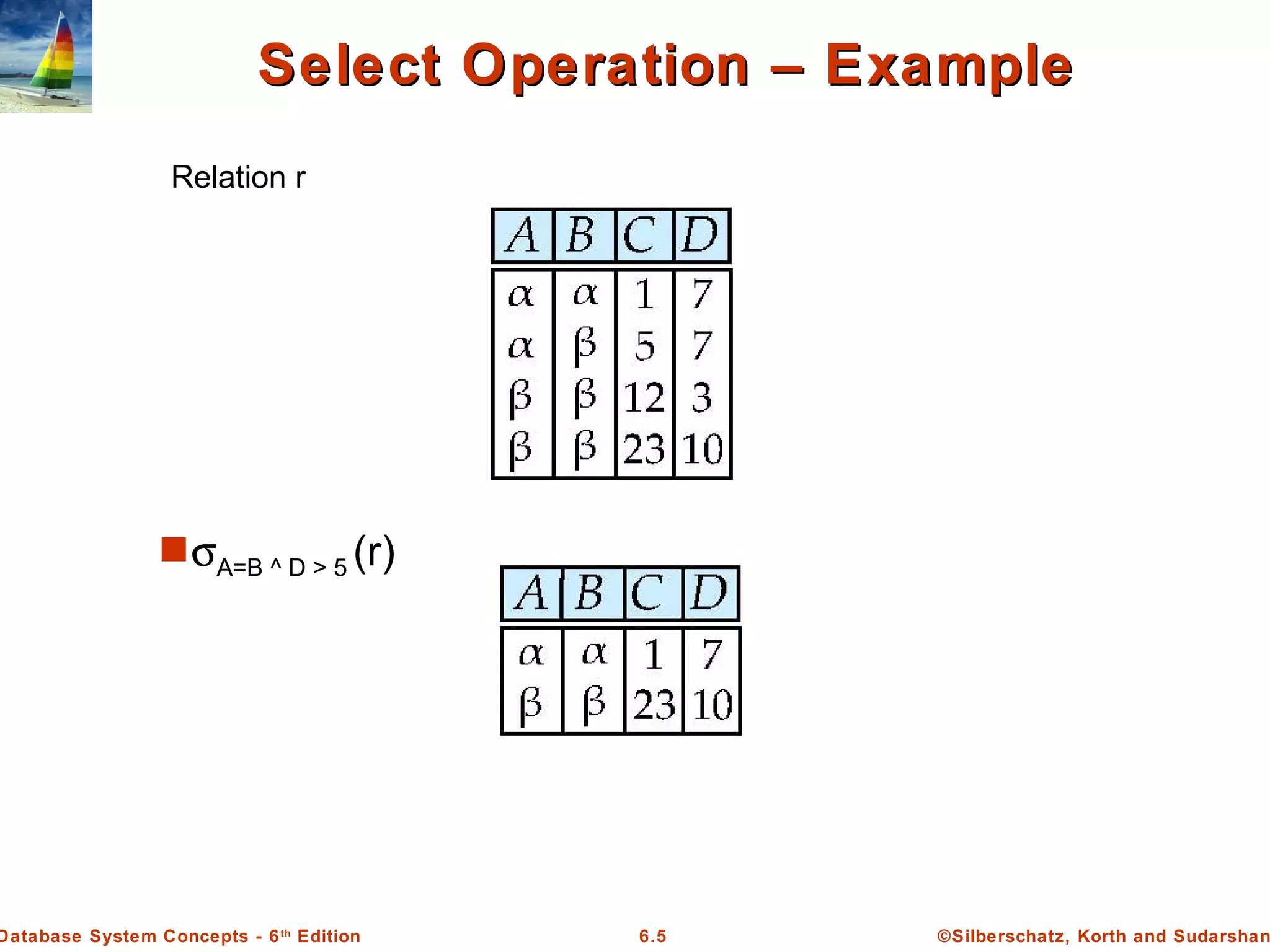

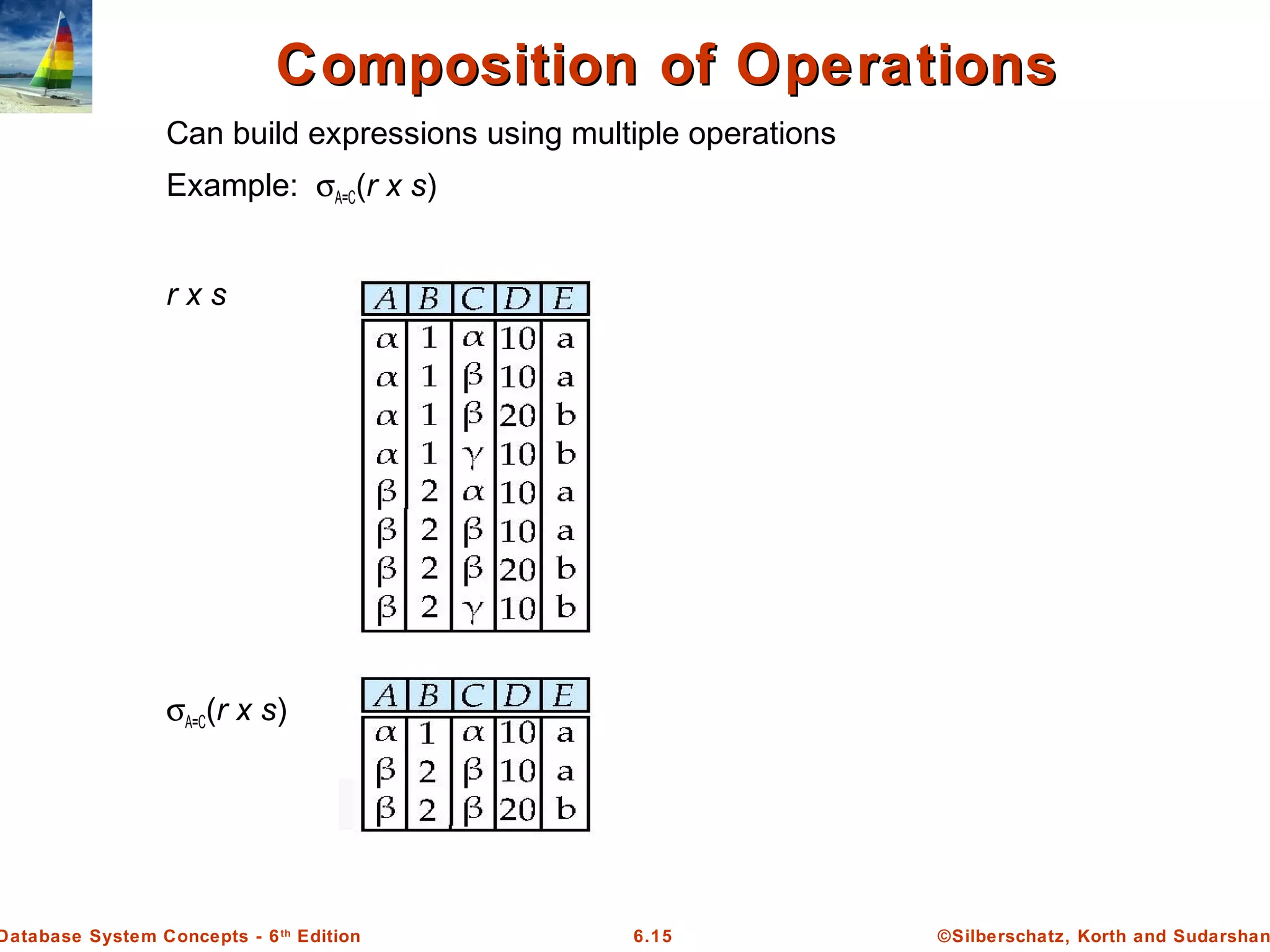

This document discusses formal relational query languages, including relational algebra, tuple relational calculus, and domain relational calculus. Relational algebra is a procedural query language that uses operators like select, project, join, and set difference. Tuple relational calculus and domain relational calculus are nonprocedural query languages that use predicates and quantifiers to specify queries. Examples of queries written in each language are provided to illustrate their syntax and capabilities.

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.17Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

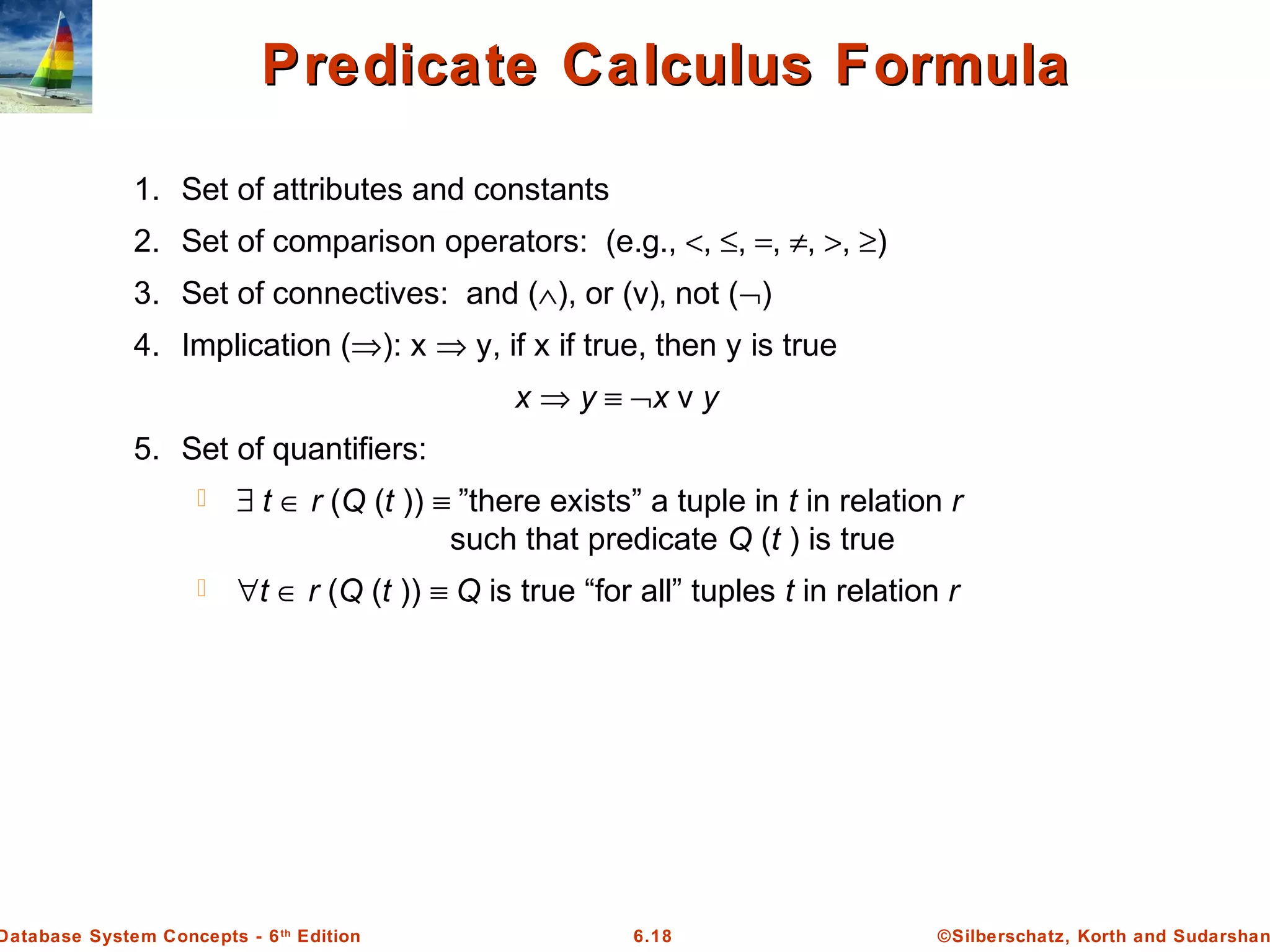

Tuple Relational CalculusTuple Relational Calculus

A nonprocedural query language, where each query is of the form

{t | P (t ) } (Query form) (P (t ) is a expression involving variable t)

It is the set of all tuples t such that predicate P is true for t

t is a tuple variable, t [A ] denotes the value of tuple t on attribute A

(Tuple variable: variable that takes on tuples of a relation schema as values.)

t ∈ r denotes that tuple t is in relation r

P is a formula similar to that of the predicate calculus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-17-2048.jpg)

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.19Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

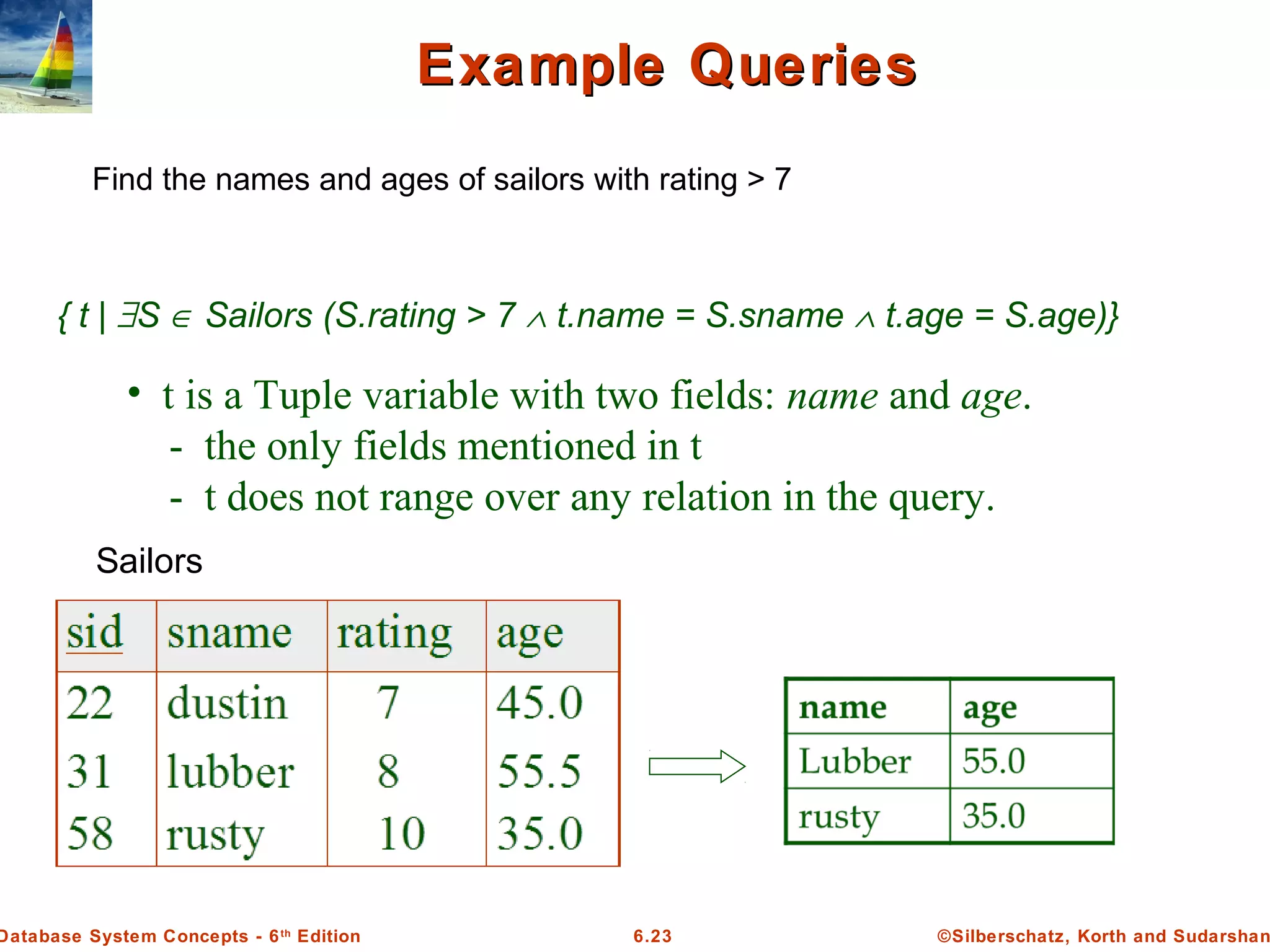

Example QueriesExample Queries

Find the ID, name, dept_name, salary for instructors whose salary is greater

than $80,000 (express on the query by using tuple relational calculus)

As in the previous query, but output only the ID attribute value

{t | ∃ s ∈ instructor (t [ID ] = s [ID ] ∧ s [salary ] > 80000)}

Notice that a relation on schema (ID) is implicitly defined by

the query

Find the ID, name of instructor who works for department Music

{t[ID], t[name] | t ∈ instructor ∧ t[dept_name] = “Music”}

{t | t ∈ instructor ∧ t [salary ] > 80000}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-19-2048.jpg)

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.20Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

Find the name, salary of instructors who teaches in department History or

Biology.

{t[name], t[salary] | t ∈ instructor (t[dept_name] = “History” v t[dept_name] = “Biology”)}

Find the ID, course_id, of all teachers who instructor for department History.

{t[ID], t[course_id] | t∈ teaches ∧ ∃ i∈ instructor (i[ID] = t[ID] ∧ d ∈ department

(d[dept_name] = i[dept_name] ∧ d[dept_name] = ‘History’))}

Find the name of the instructor who teaches in every course.

{t[name] І t ∈ instructor ∧ ∀ s ∈ course (u ∈ teaches (u[ID] = t[ID] ∧ s [course_id] = u

[course_id]))}

Find the names of the students who have no advisor.

{t[name] І t ∈student ∧ ¬ (∃ s∈ advisor (s[s_id] = t[ID]))}

Example QueriesExample Queries](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-20-2048.jpg)

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.21Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

Example QueriesExample Queries

Find the names of all instructors whose department is in the Watson

building

{t | ∃s ∈ section (t [course_id ] = s [course_id ] ∧

s [semester] = “Fall” ∧ s [year] = 2009

v ∃u ∈ section (t [course_id ] = u [course_id ] ∧

u [semester] = “Spring” ∧ u [year] = 2010)}

Find the set of all courses taught in the Fall 2009 semester, or in

the Spring 2010 semester, or both

{t | ∃s ∈ instructor (t [name ] = s [name ]

∧ ∃u ∈ department (u [dept_name ] = s[dept_name] “

∧ u [building] = “Watson” ))}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-21-2048.jpg)

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.22Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

Example QueriesExample Queries

{t | ∃s ∈ section (t [course_id ] = s [course_id ] ∧

s [semester] = “Fall” ∧ s [year] = 2009

∧ ∃u ∈ section (t [course_id ] = u [course_id ] ∧

u [semester] = “Spring” ∧ u [year] = 2010)}

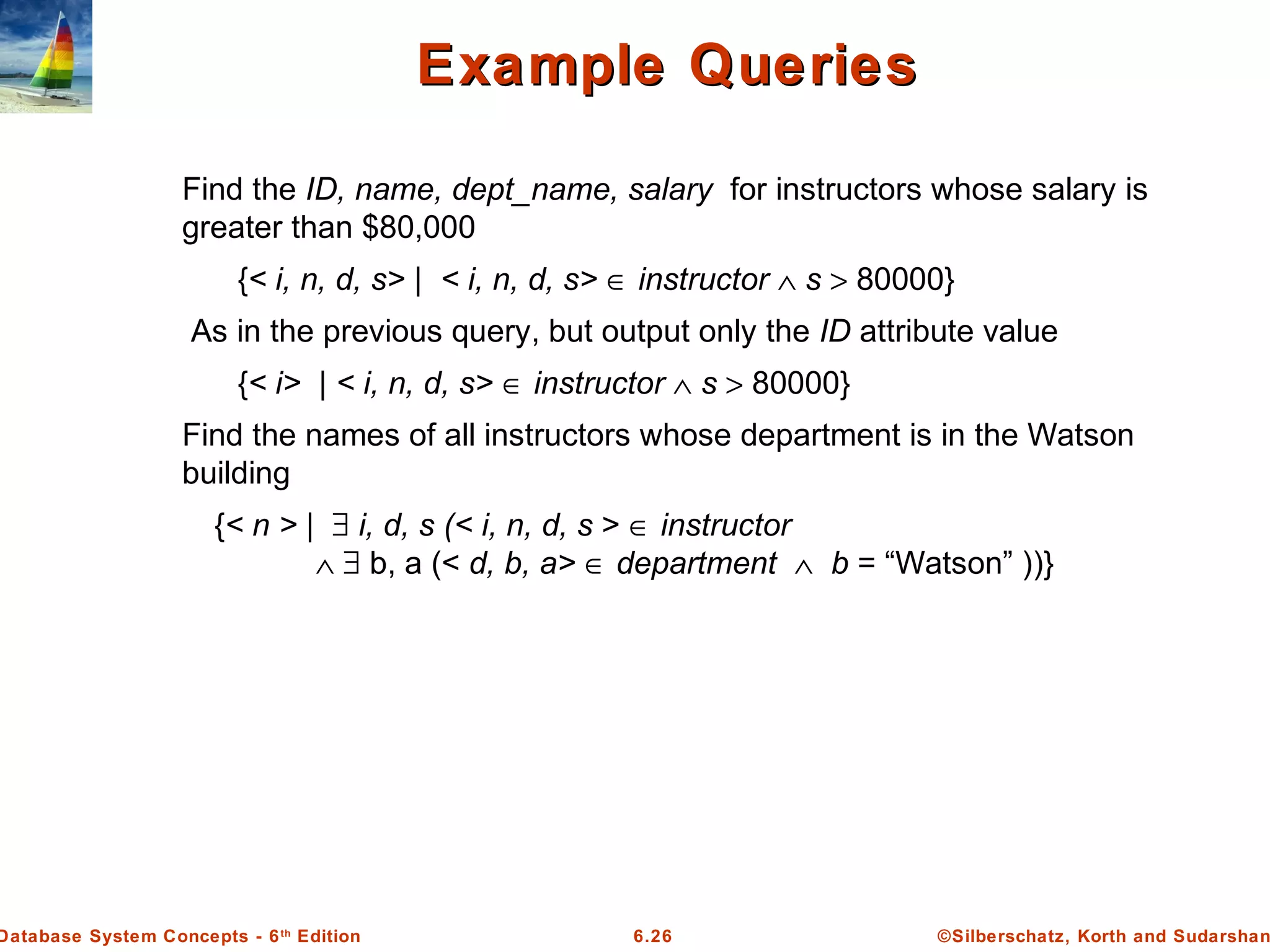

Find the set of all courses taught in the Fall 2009 semester, and in

the Spring 2010 semester

{t | ∃s ∈ section (t [course_id ] = s [course_id ] ∧

s [semester] = “Fall” ∧ s [year] = 2009

∧ ¬ ∃u ∈ section (t [course_id ] = u [course_id ] ∧

u [semester] = “Spring” ∧ u [year] = 2010)}

Find the set of all courses taught in the Fall 2009 semester, but not in

the Spring 2010 semester](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-22-2048.jpg)

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan6.27Database System Concepts - 6th

Edition

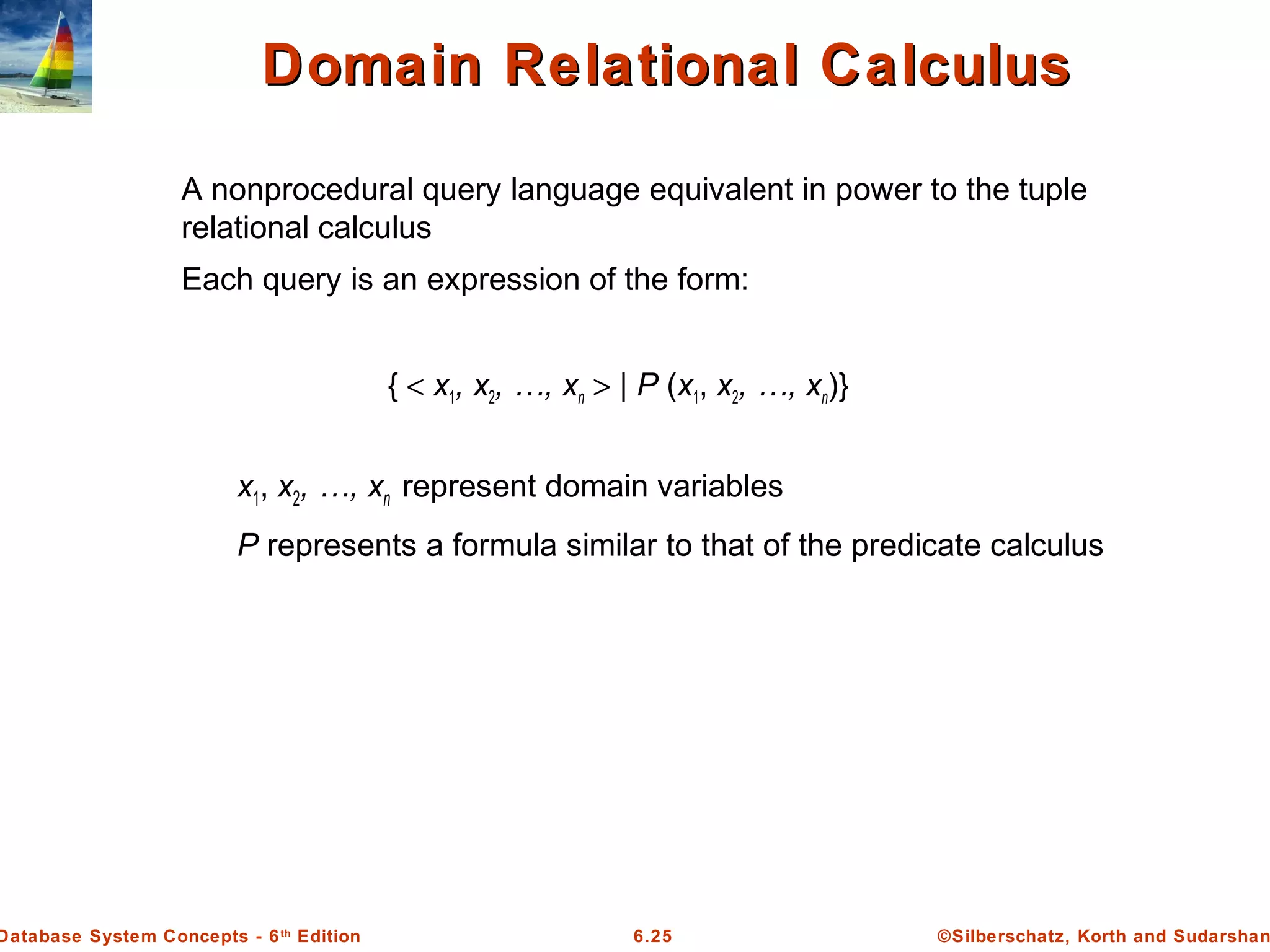

Example QueriesExample Queries

{<c> | ∃ a, s, y, b, r, t ( <c, a, s, y, b, t > ∈ section ∧

s = “Fall” ∧ y = 2009 )

v ∃ a, s, y, b, r, t ( <c, a, s, y, b, t > ∈ section ] ∧

s = “Spring” ∧ y = 2010)}

Find the set of all courses taught in the Fall 2009 semester, or in

the Spring 2010 semester, or both

This case can also be written as

{<c> | ∃ a, s, y, b, r, t ( <c, a, s, y, b, t > ∈ section ∧

( (s = “Fall” ∧ y = 2009 ) v (s = “Spring” ∧ y = 2010))}

Find the set of all courses taught in the Fall 2009 semester, and in

the Spring 2010 semester

{<c> | ∃ a, s, y, b, r, t ( <c, a, s, y, b, t > ∈ section ∧

s = “Fall” ∧ y = 2009 )

∧ ∃ a, s, y, b, r, t ( <c, a, s, y, b, t > ∈ section ] ∧

s = “Spring” ∧ y = 2010)}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch6formalrelationalquerylanguages-151017214000-lva1-app6892/75/Ch6-formal-relational-query-languages-27-2048.jpg)