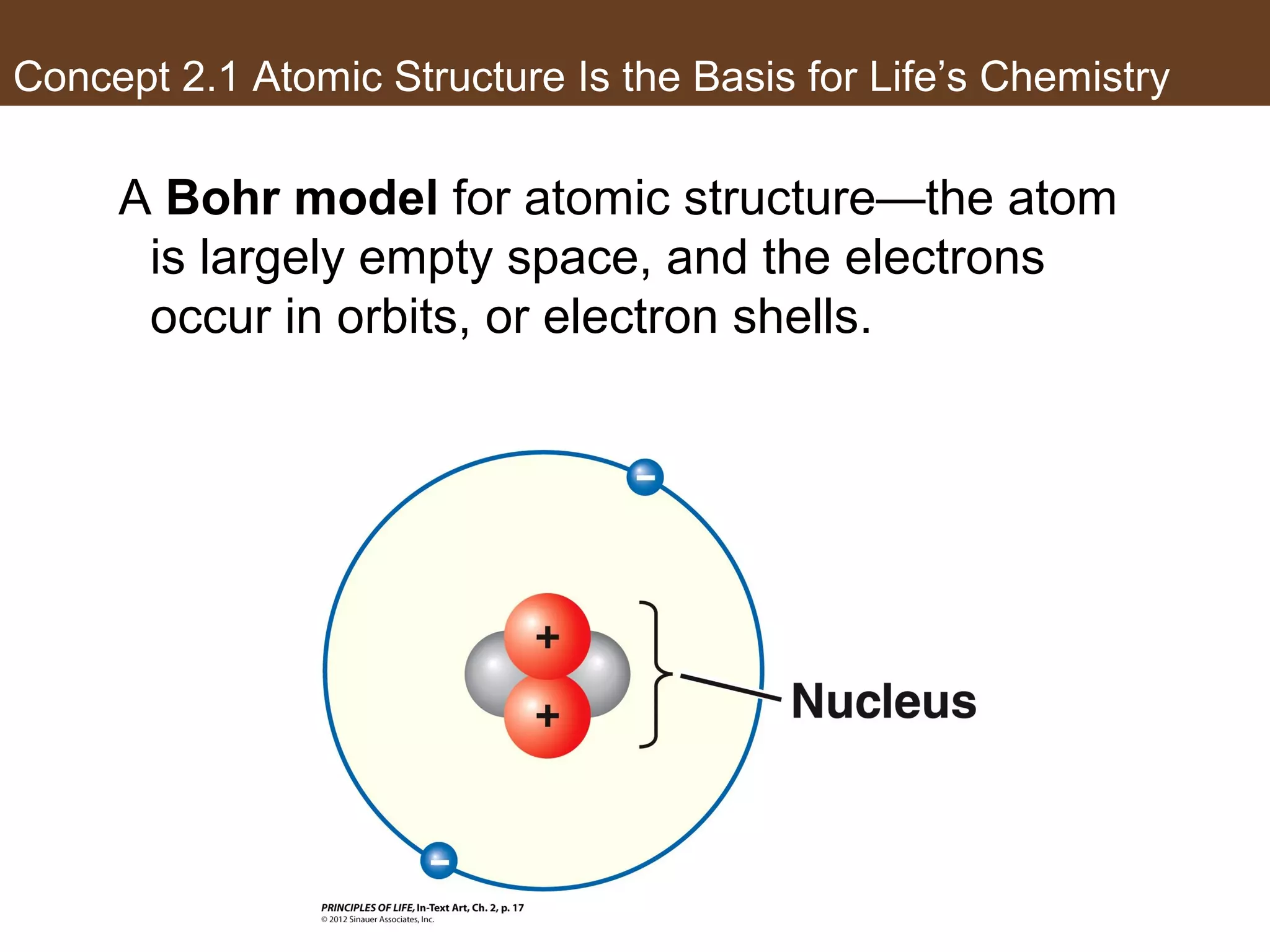

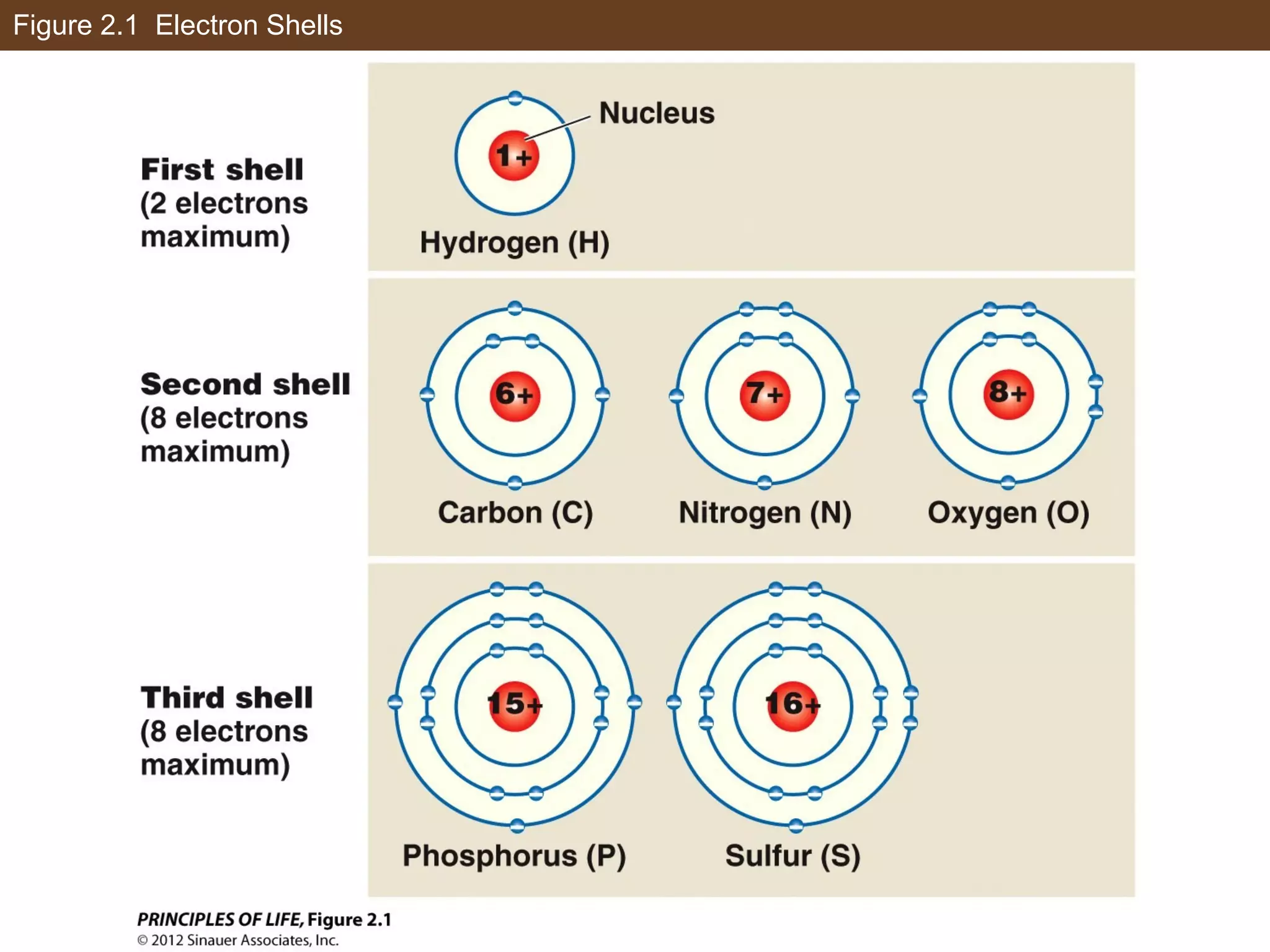

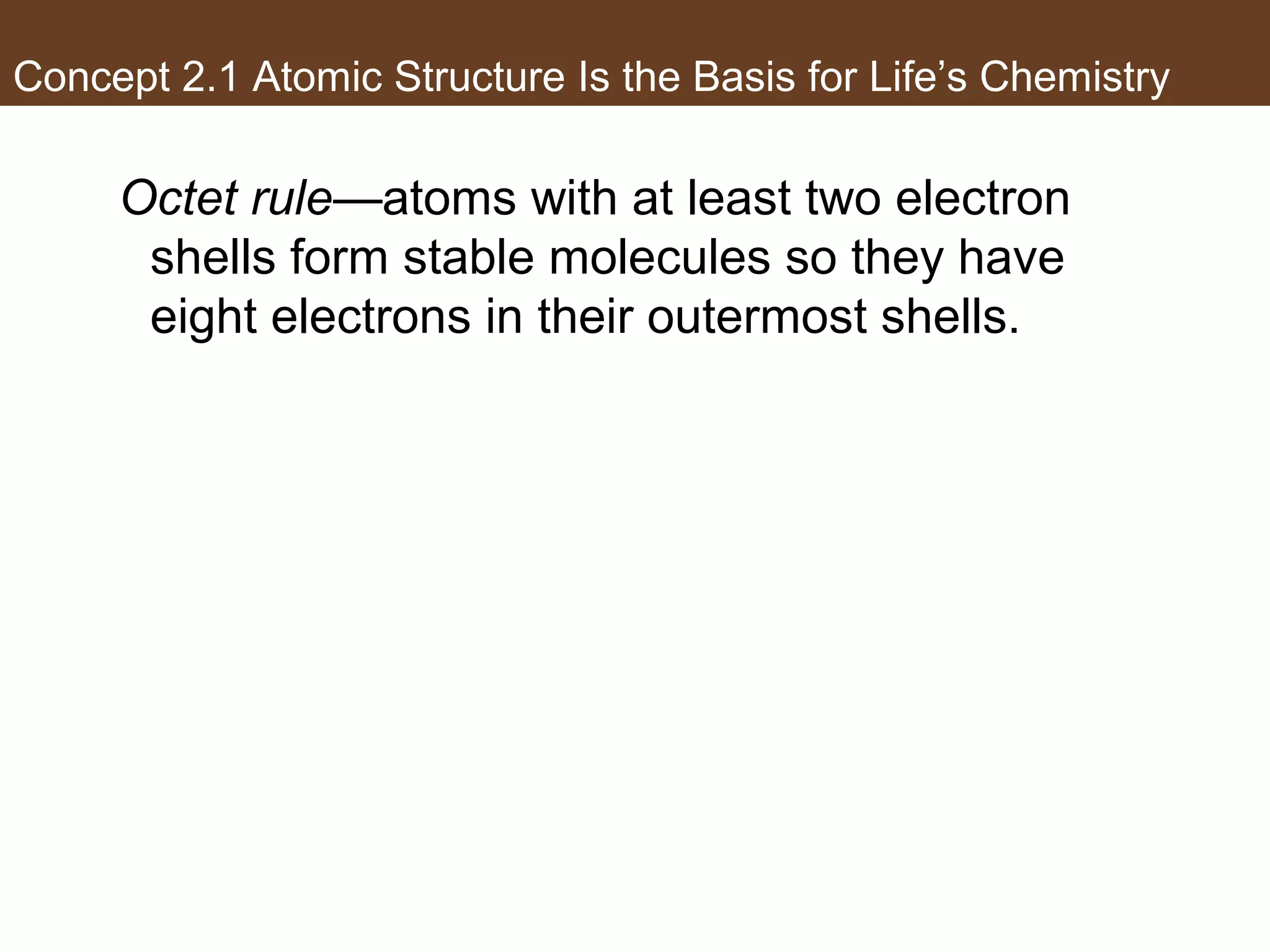

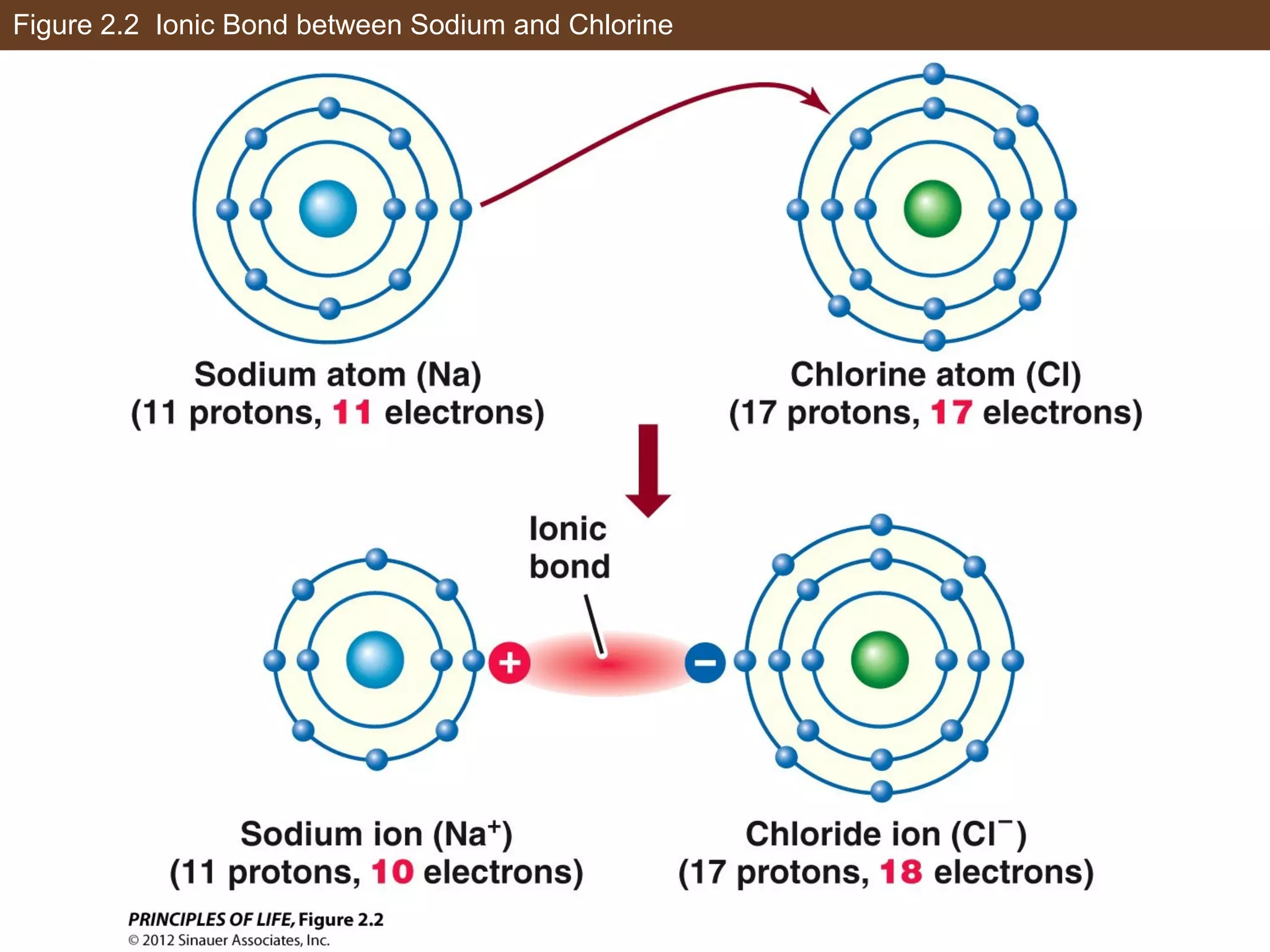

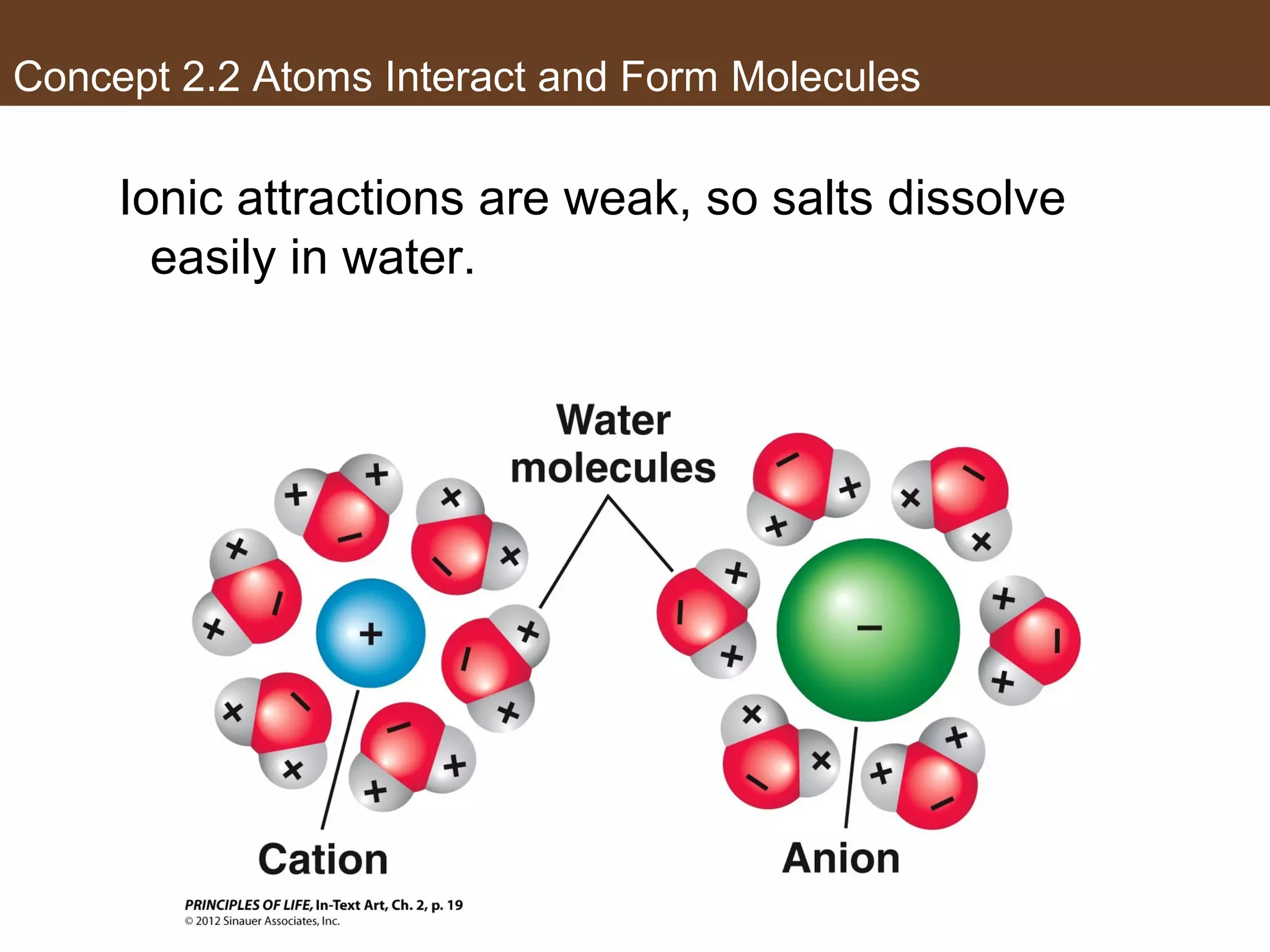

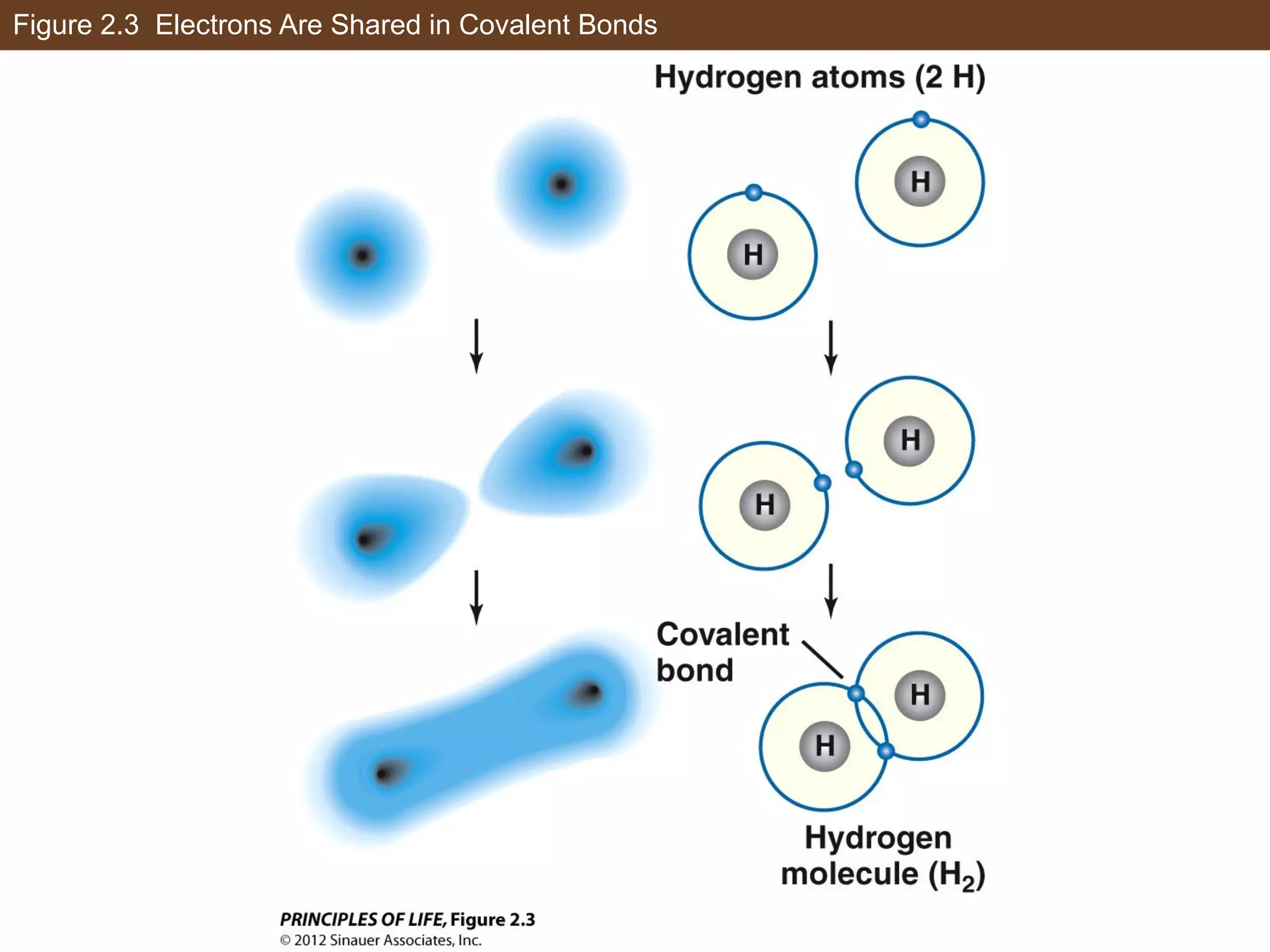

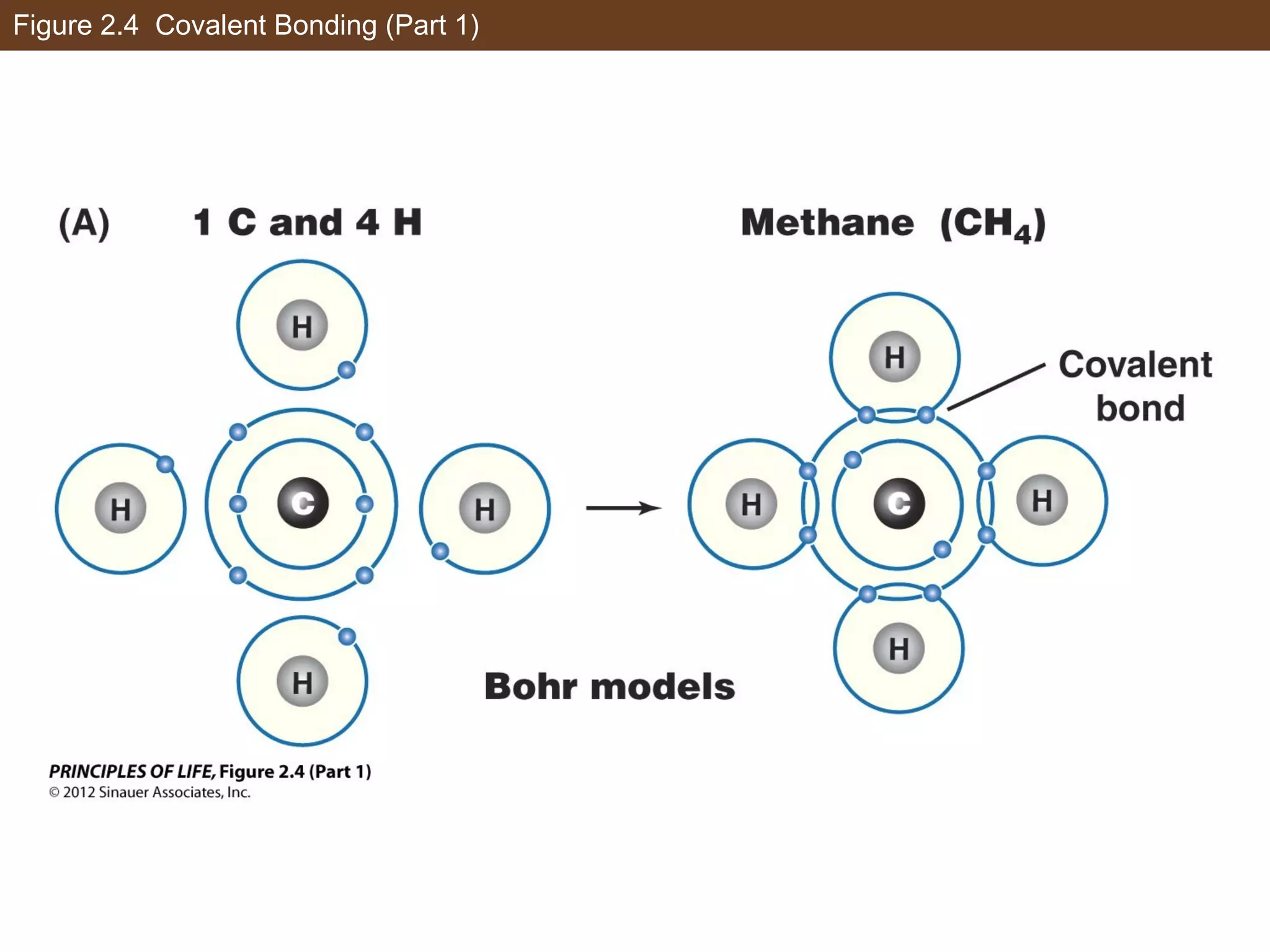

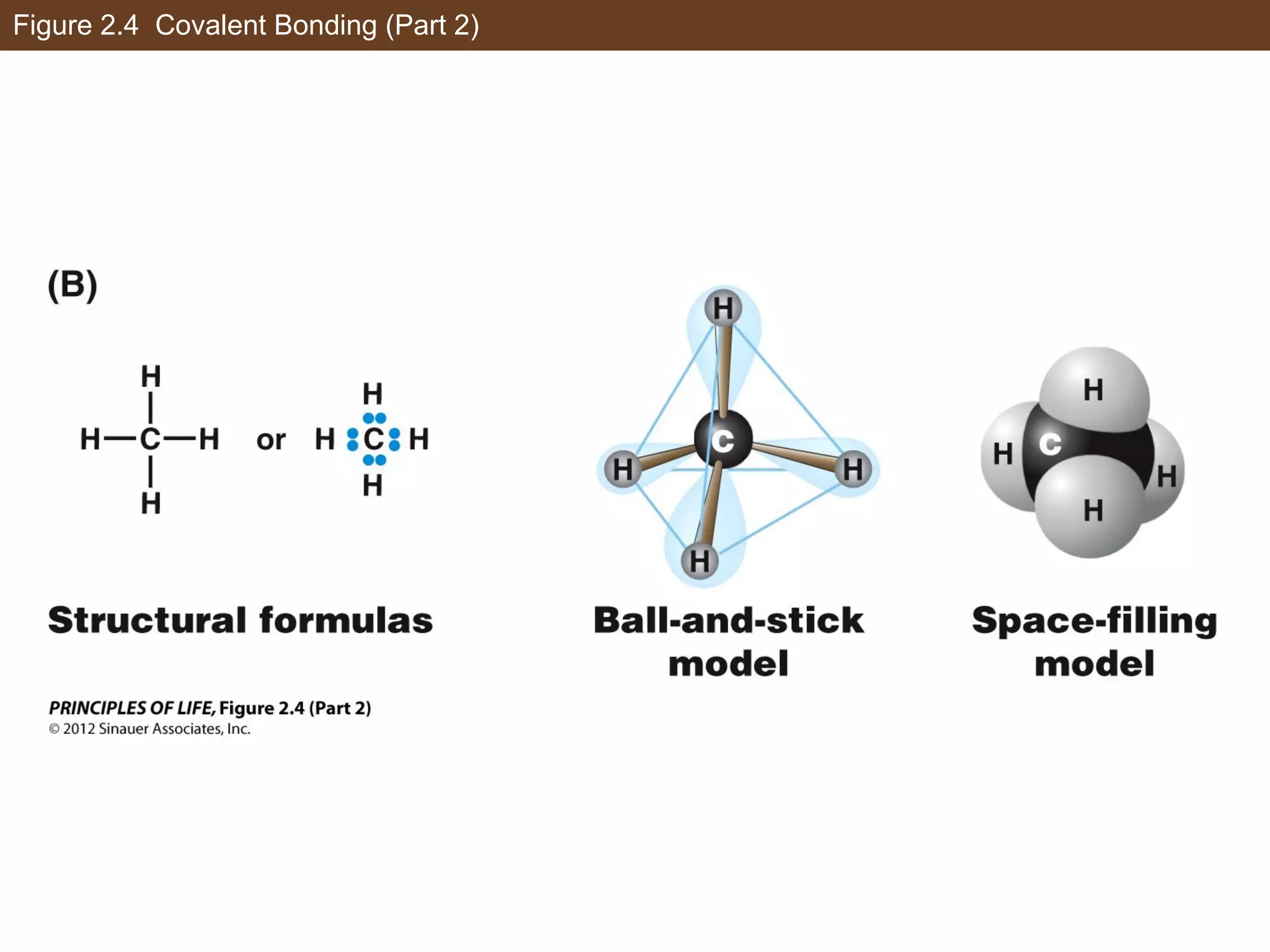

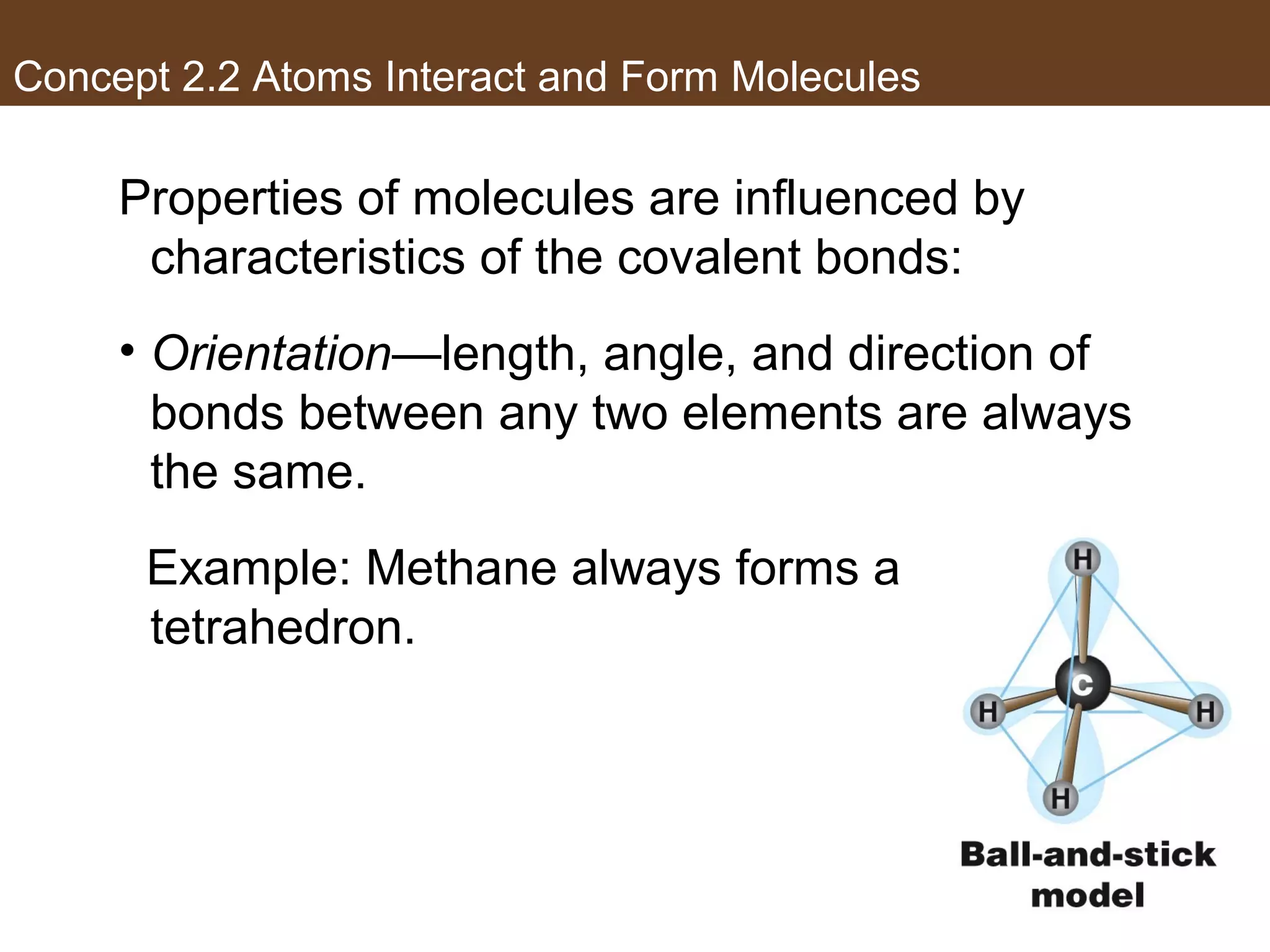

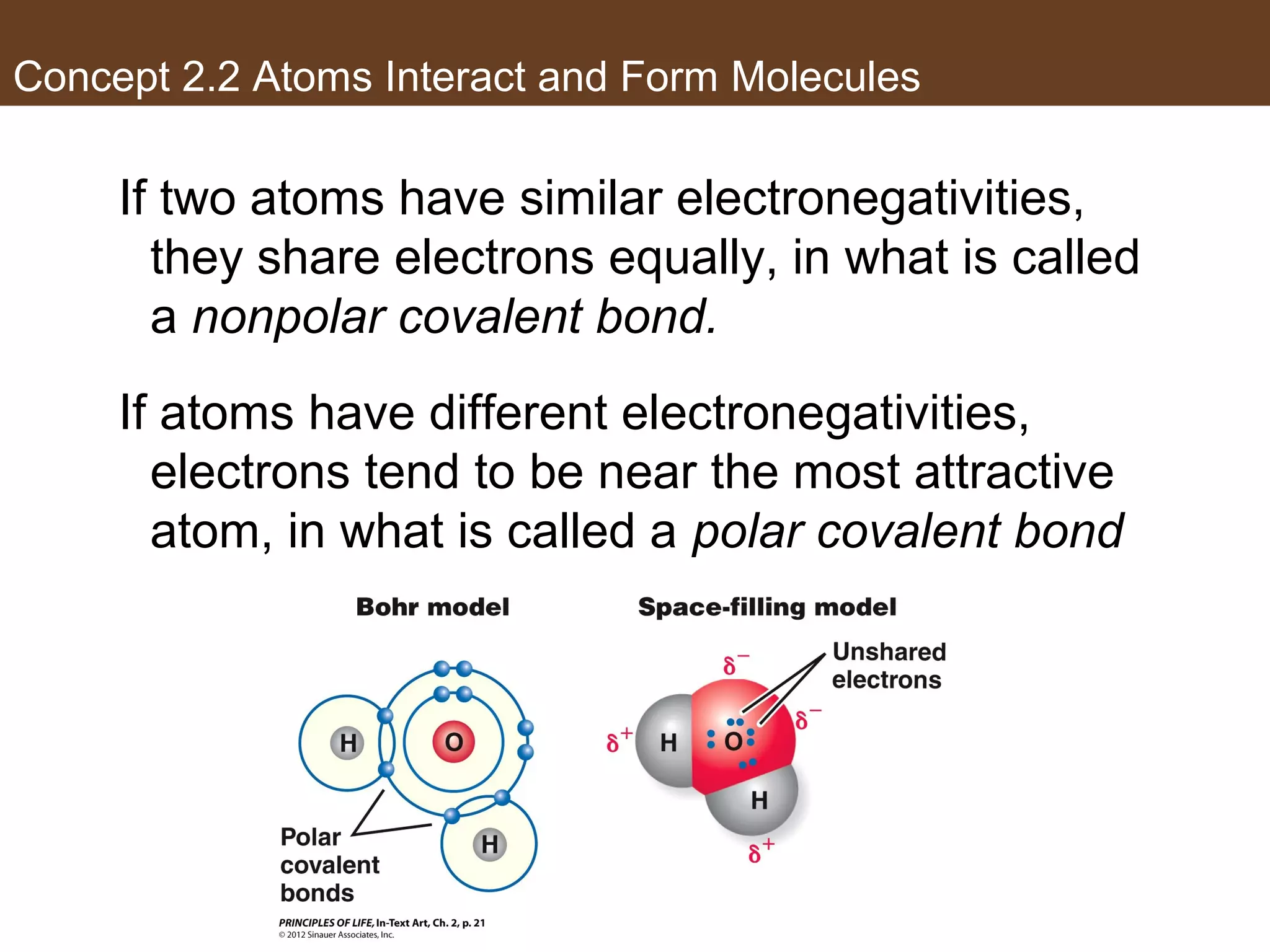

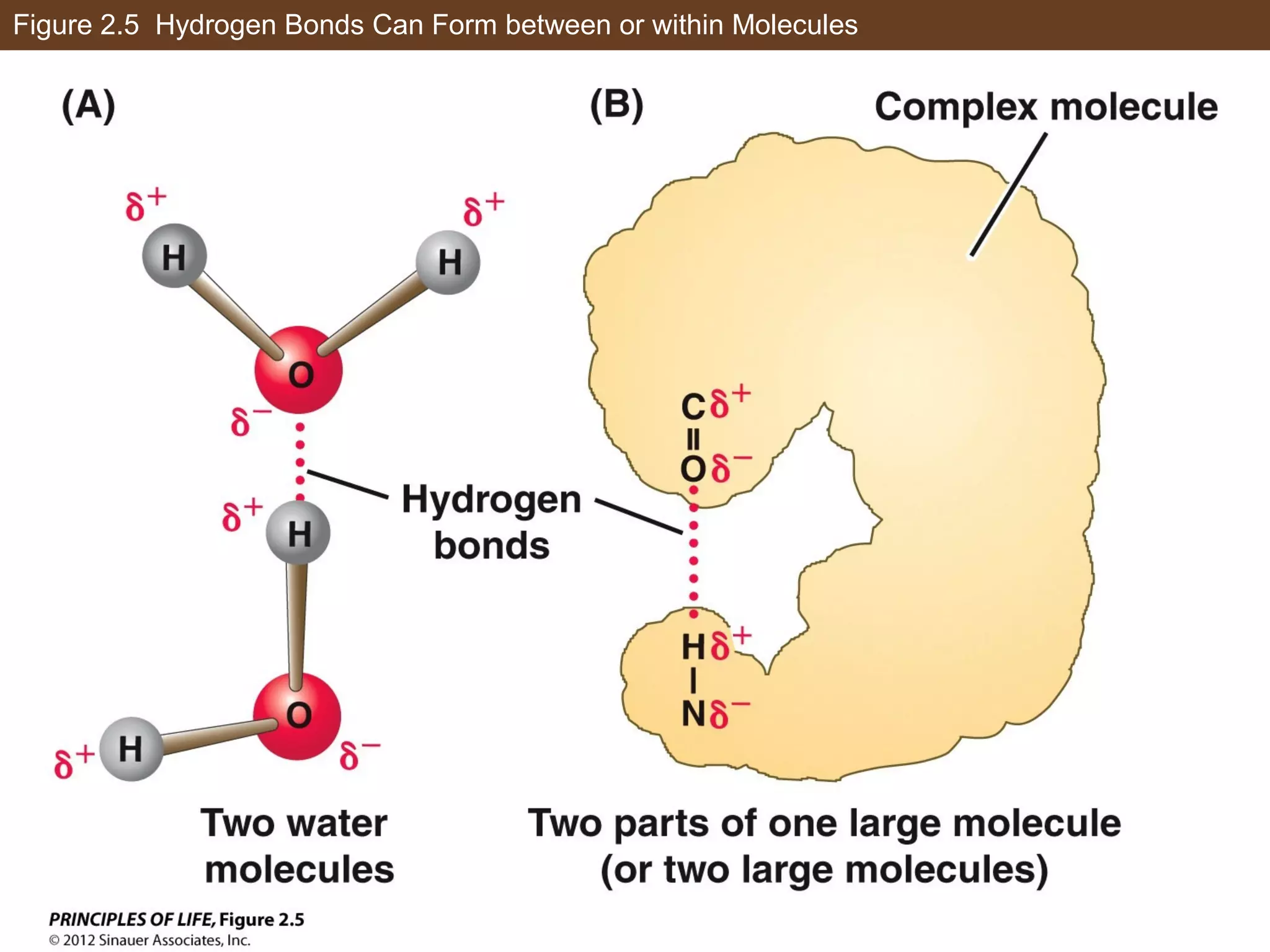

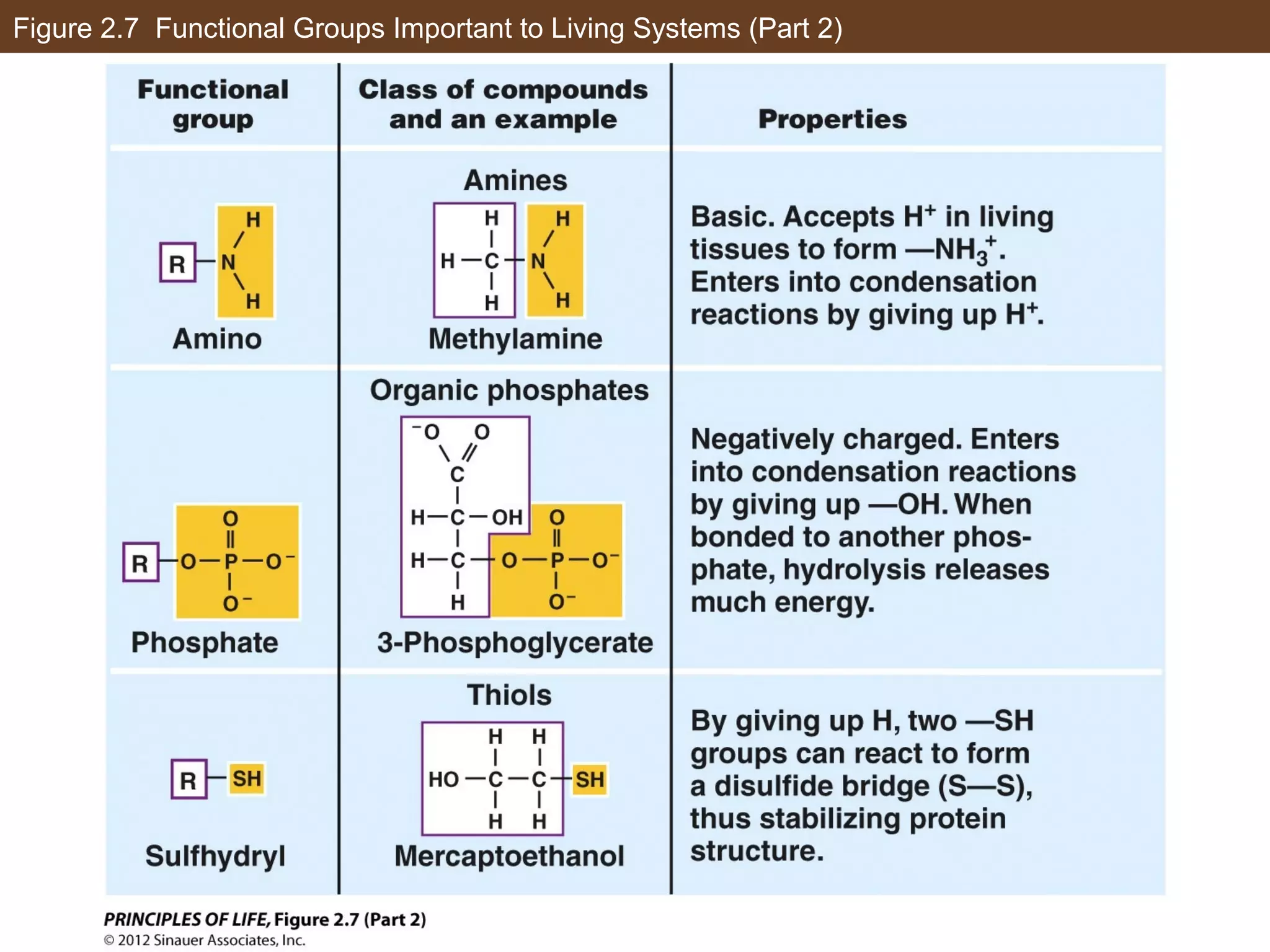

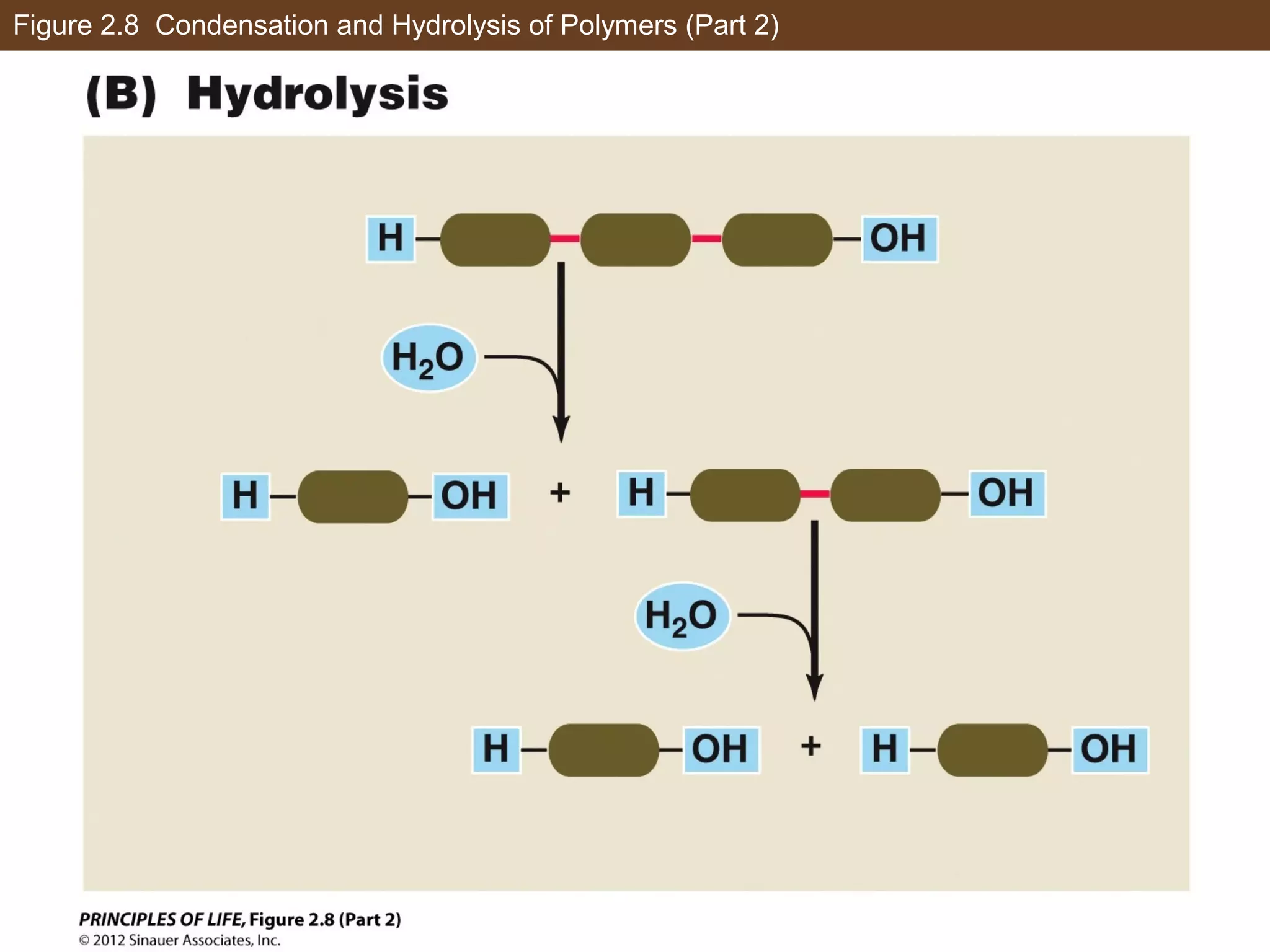

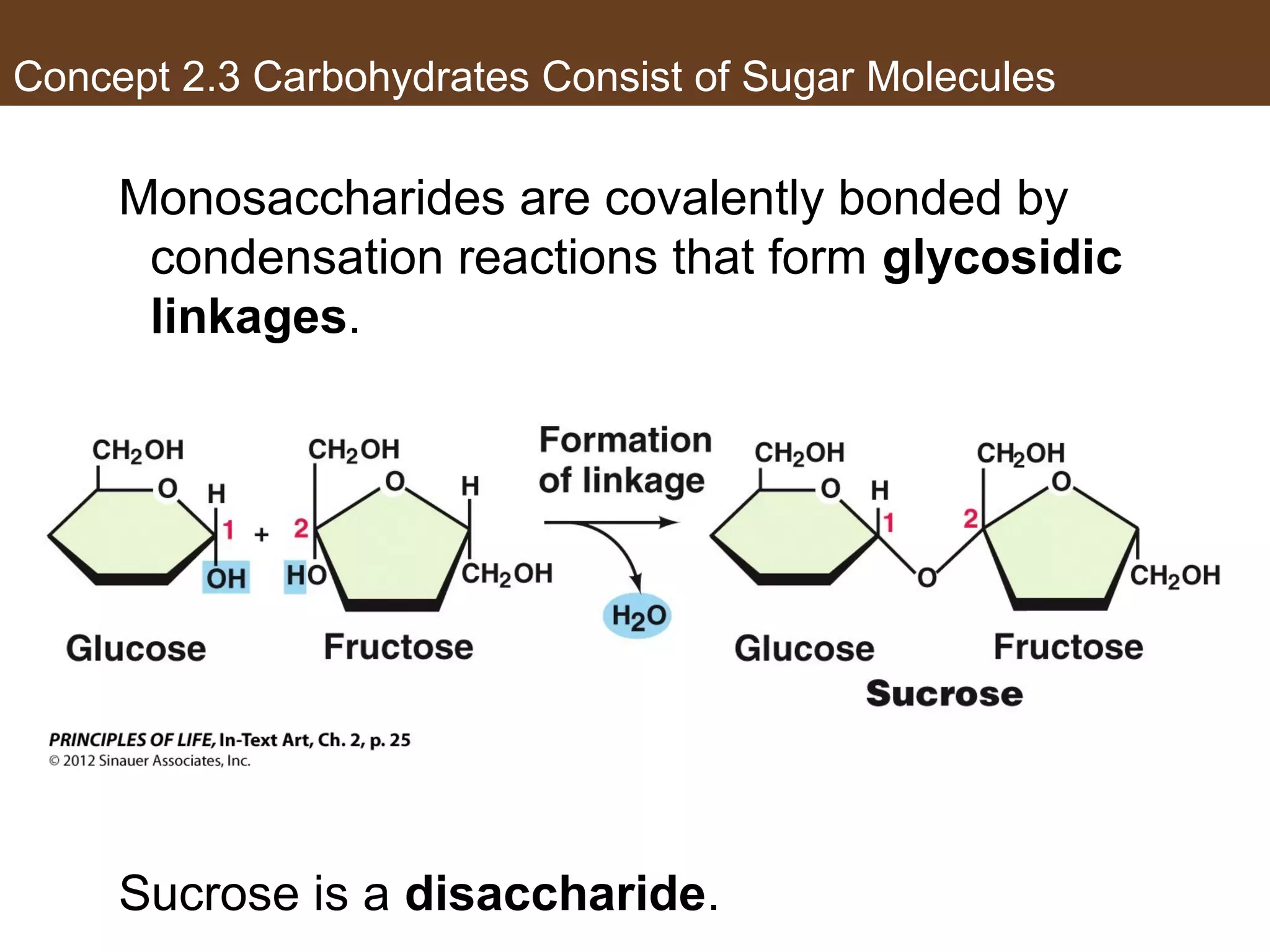

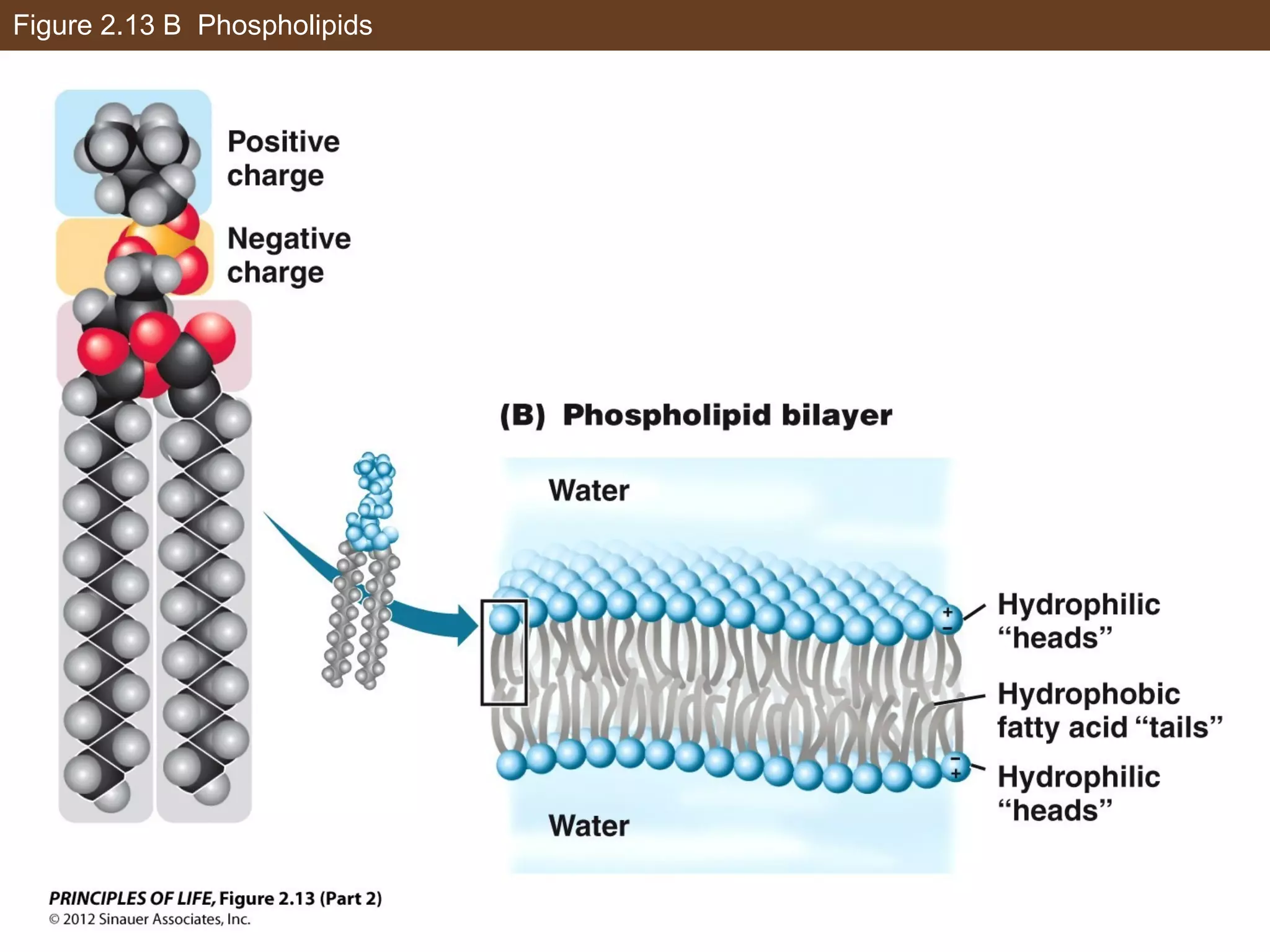

This document discusses life chemistry and energy. It begins by explaining atomic structure and the 6 main elements that make up living things. It then discusses how atoms interact and form molecules through various bonds like ionic bonds, covalent bonds, and hydrogen bonds. Carbohydrates consist of sugar molecules that are linked together, while lipids are hydrophobic molecules that store energy. Biochemical changes involve energy transfers through reactions.