This report, prepared within the ENEPO project, examines the development gaps among EU neighboring countries, focusing on economic, human, environmental, and institutional dimensions. It aims to assess trends and origins of these gaps, which could impact social and economic integration with the EU, and includes a comprehensive analysis based on quantitative and qualitative methods. The authors, experts in various fields, highlight notable issues related to each dimension, providing insights for policy-making and research.

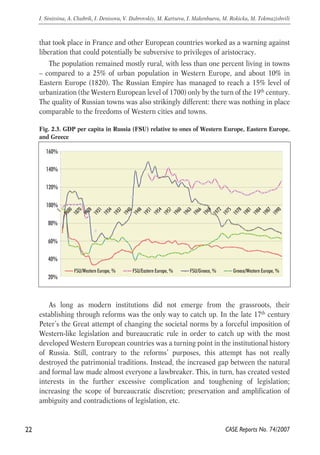

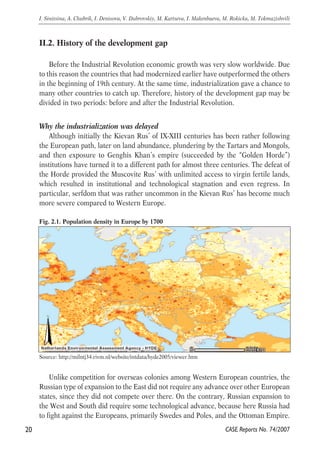

![Still, despite Peter the Great’s attempt of institutional and technological catch-up in the

beginning of the 18th century, by the beginning of Industrial Revolution the Russian

Empire remained mostly agrarian. It remained such for quite a long period of time

with less than one percent of urban population compared to fifteen percent in the

Western Europe, and 5.65% in the Eastern Europe by 1720.

Authoritarianism was an essential part of any agrarian empire, and Russia was not

an exception, remaining an absolute monarchy until the early 20th century. Serfdom

that lasted until 1861 made labor mobility close to zero. Instead, modern industries

were run mostly by the state that, in its turn, was also using mostly forced labor. At the

same time, the bureaucracy and other institutions of rational rule were largely formal,

while the actual rules remained inherited from the patrimonial state17. The rule of law

and other institutions needed for complex transactions going beyond simple bazaar

exchange remained weak, so the financial markets were non-existing. Therefore, not

only the industrialization did not start, but the most necessary preconditions for a

“market capitalist” kind of industrialization were missed along with driving forces for it.

Fig. 2.2. GDP per capita in Russia (FSU) compared to Europe and Greece

18,000

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

0

1

1600

1870

1928

1931

1954

1957

1960

1963

1966

1969

1972

1975

1978

By this time the Russian Empire was already one of the largest in the world by its

territory having, however, very little density of population even in its most developed

European part (Fig. 2.1), abundant with virgin lands, having a severe serfdom and

with very weak incentives for entrepreneurship. Examples of bourgeois revolutions

21

ASSESSING THE DEVELOPMENT GAP

17 Volkov, V. (2000). “Patrimonialism versus Rational Bureaucracy: on the Historical Relativity of Corruption”

[in:] S. Lovell, A. V. Ledeneva, and A. Rogachevskii (ed.), Bribery and Blat in Russia: Negotiating Reciprocity

from the Middle Ages to the 1990, School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies, University of London.

McMillan.

CASE Reports No. 74/2007

1934

1937

1940

1948

1951

1981

1984

1987

1990

1990 Int'l Geary-Khamis $

Greece

Western Europe (29 countries)

FSU/Russia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cnr74-141022094859-conversion-gate01/85/CASE-Network-Reports-74-Assessing-the-Development-Gap-21-320.jpg)