The document presents a comprehensive analysis of labour migration from Eastern Partnership (EAP) countries to the EU, assessing the costs and benefits of such mobility. It identifies three significant stages of migration influenced by historical, economic, and social factors, highlighting different patterns in various EAP countries. The analysis aims to inform policy recommendations that could enhance the positive outcomes of migration for these countries.

![LABOUR MIGRATION FROM THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP COUNTRIES…

CASE 69 Network Reports No. 113

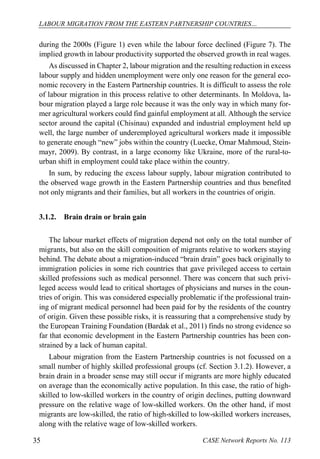

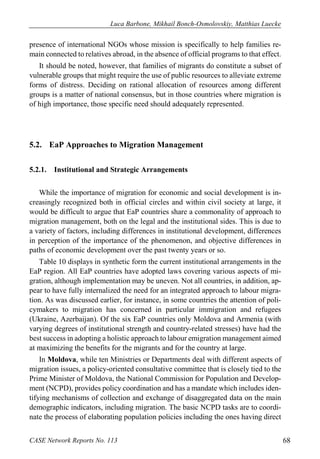

relations with international migration. The Action Plan (2011-2015) for the Imple- mentation of the National Strategy on Migration and Asylum (2011-2020) provides the legal and operational framework for the NCPD.

Armenia (which, as noted in earlier sections, has the highest percentage of la- bour migrants to the Russian Federation) stands out for its attempts to facilitate the use of the Diaspora as a powerful tool for development (see Box 1). It has had a Ministry for Diaspora Affairs since 2008, and several other public and private or- ganizations have been active in the area of Diaspora development. However, the Country Study notes that in other areas of migration management and strategy, Ar- menia has yet to develop a clear institutional framework with assignment of respon- sibilities for the many issues concerned. This is in effect the reflection of the con- tinuing lack of an overall Migration Strategy as a national priority document with capacity to affect decisions in all important areas.

Ukraine contributes the largest amount of labour migrants for the EaP countries, given its sheer size. However, the Country Paper notes that “The Concept of State Migration Policy was adopted only in the middle of 2011, after over fifteen years of discussion in parliament and other state bodies. Hence, Ukraine never really con- sidered migration policy to be a priority. Instead, it tried to control immigration while doing little for Ukrainians working abroad. For example, the State Migration Service has a “Plan of Integration of [Im]migrants into Ukrainian Society for 2011- 2015” but nothing for emigrants”.

Table 10. Legal and institutional Arrangements for Migration in EaP Countries

Country

Official Strategy for Labour Migration

Intra-Government Co- ordinating Mechanism

Diaspora Policies and Institutions

Armenia

Law on the Organiza- tion of Overseas Em- ployment (2010); "2012-2016 Action Plan for Implementation of the State Policy on Mi- gration Regulation in the RA" (2011)

No Policy body in place; State Migration Agency (a department of the Min- istry of Territorial Ad- ministration) is tasked with implementation of migration-related pro- jects.

Ministry for Diaspora Affairs

Azerbaijan

State Migration Pro- gramme (expired 2008)

State Migration Service within the Ministry of In- ternal Affairs (not a pol- icy-making or coordinat- ing agency)

State Committee on Work with the Dias- pora

Belarus

Strategy mostly con- cerned with internal mi- gration and immigra- tion. National Migration

No single body embraces all the activities and is- sues associated with mi- gration within a unified conceptual framework

Diaspora organisation of Belarusians of the world "Batskaush- chyna" (NGO)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cnr2013113-141015052846-conversion-gate02/85/CASE-Network-Report-113-Labour-Migration-from-the-Eastern-Partnership-Countries-Evolution-and-Policy-Options-for-Better-Outcmoes-69-320.jpg)