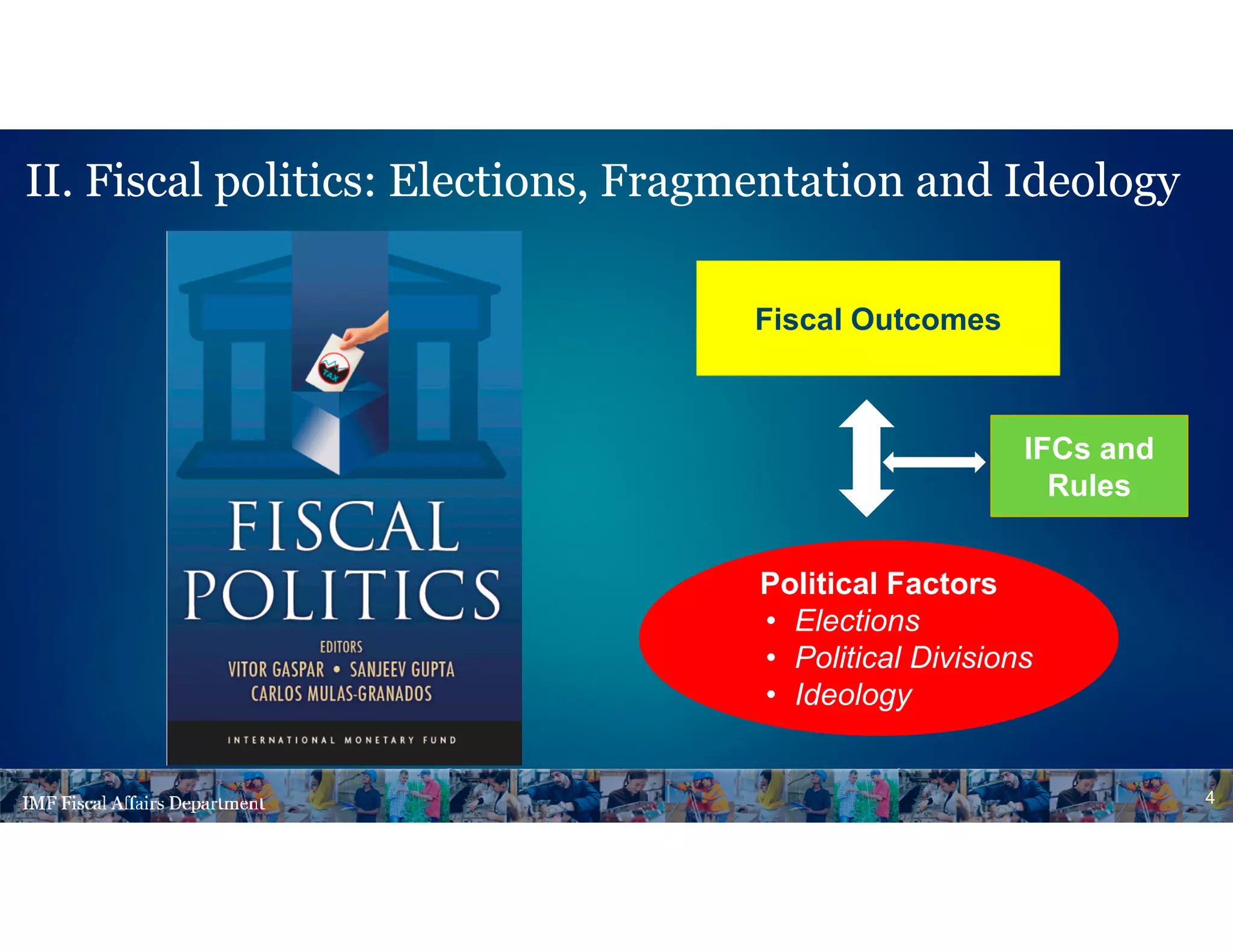

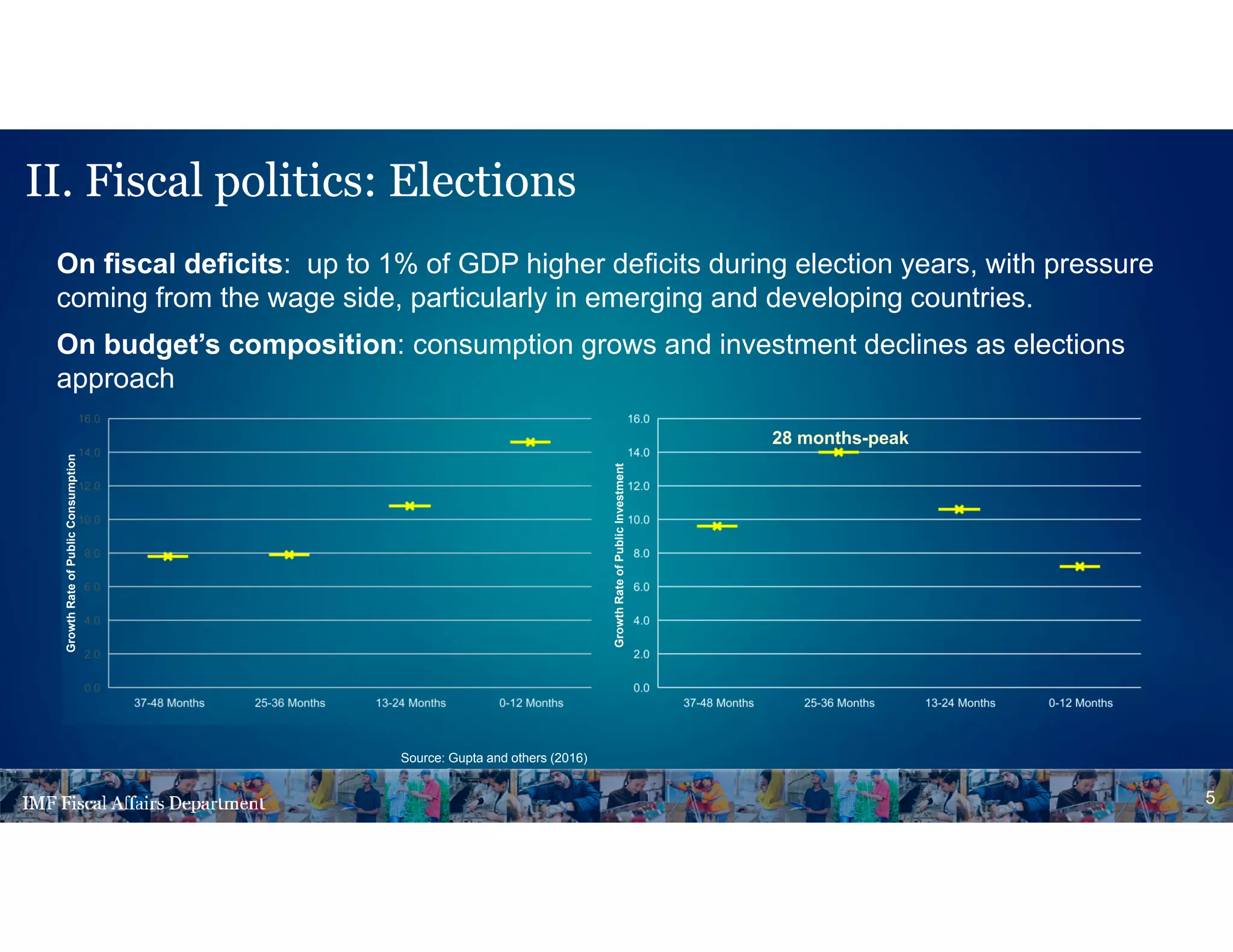

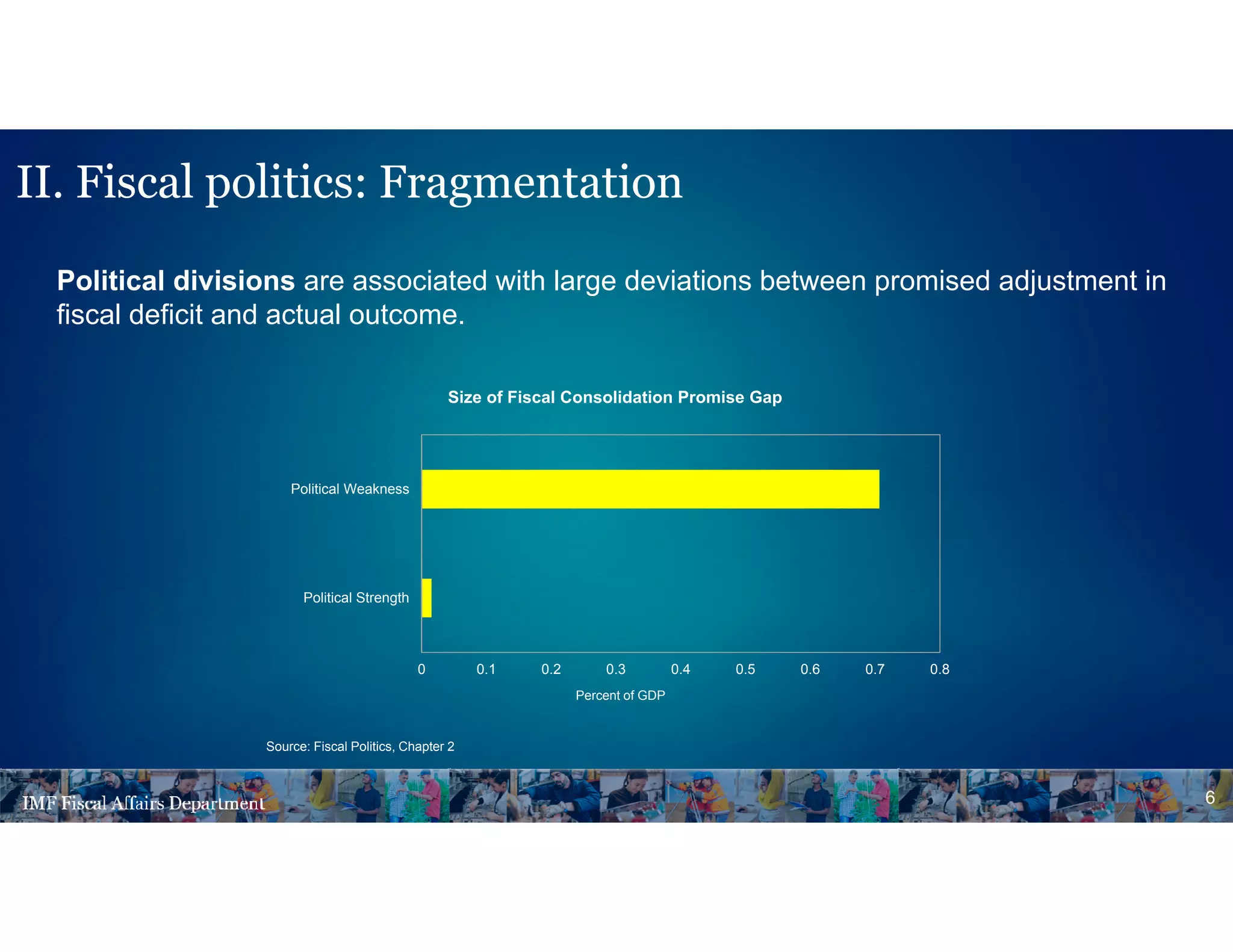

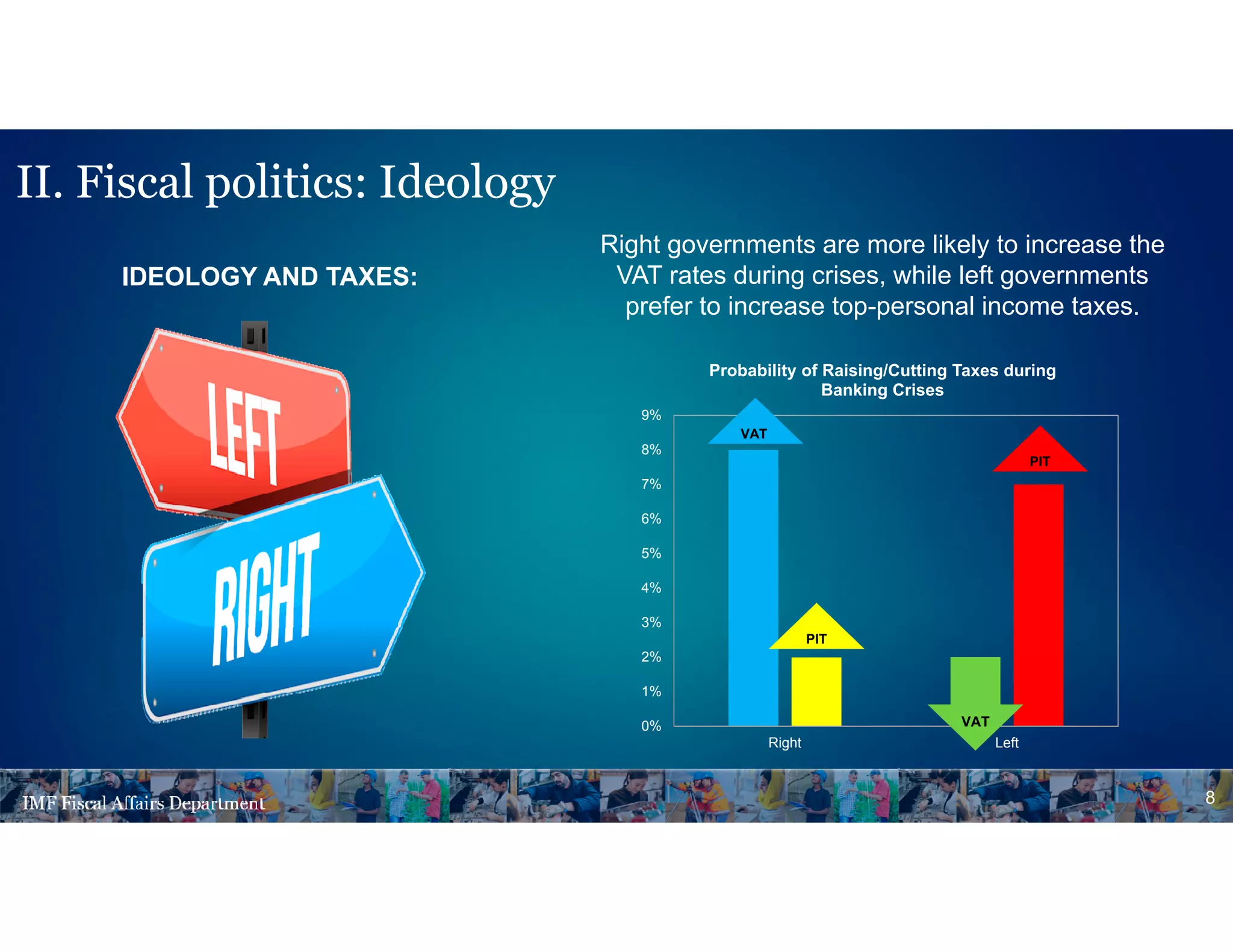

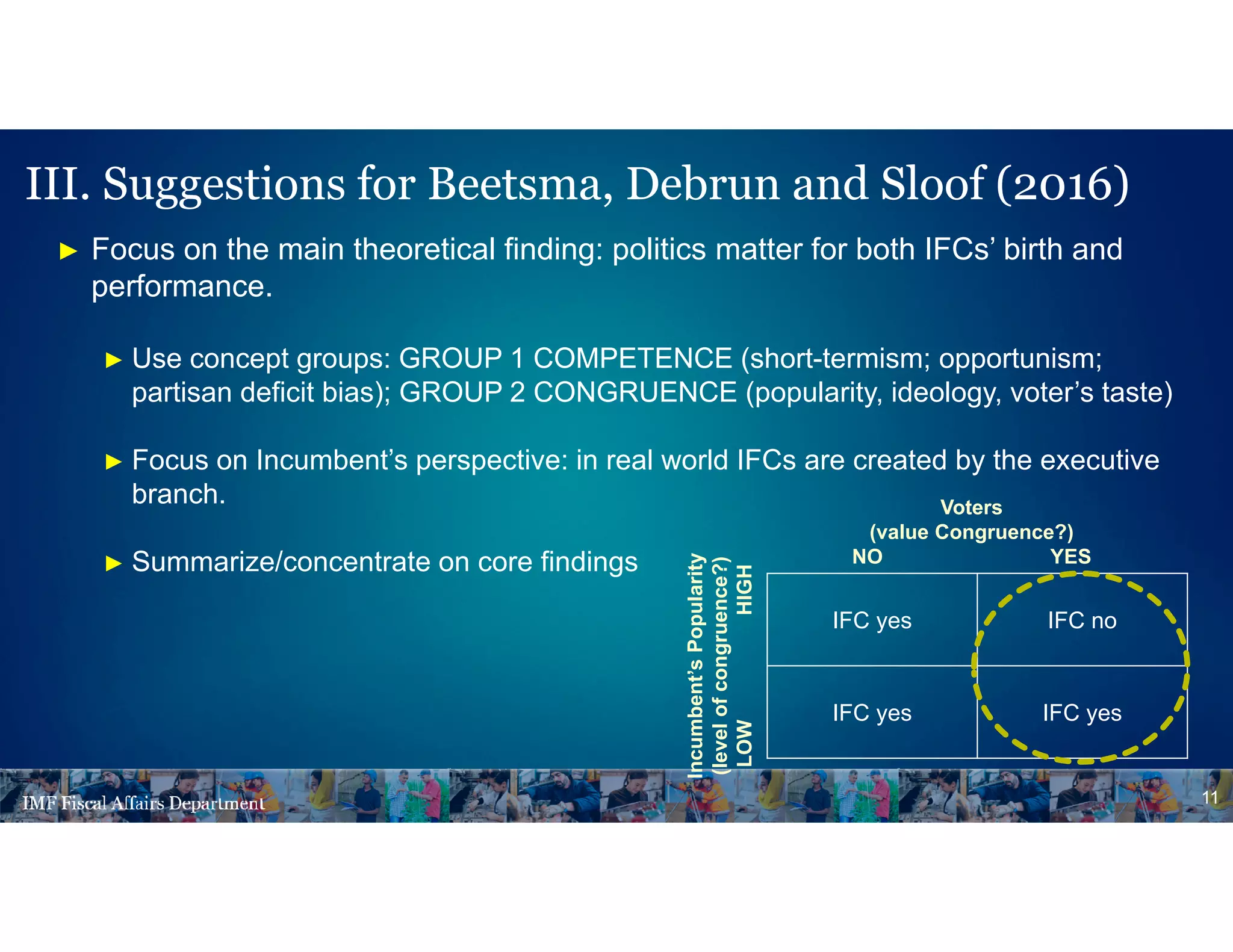

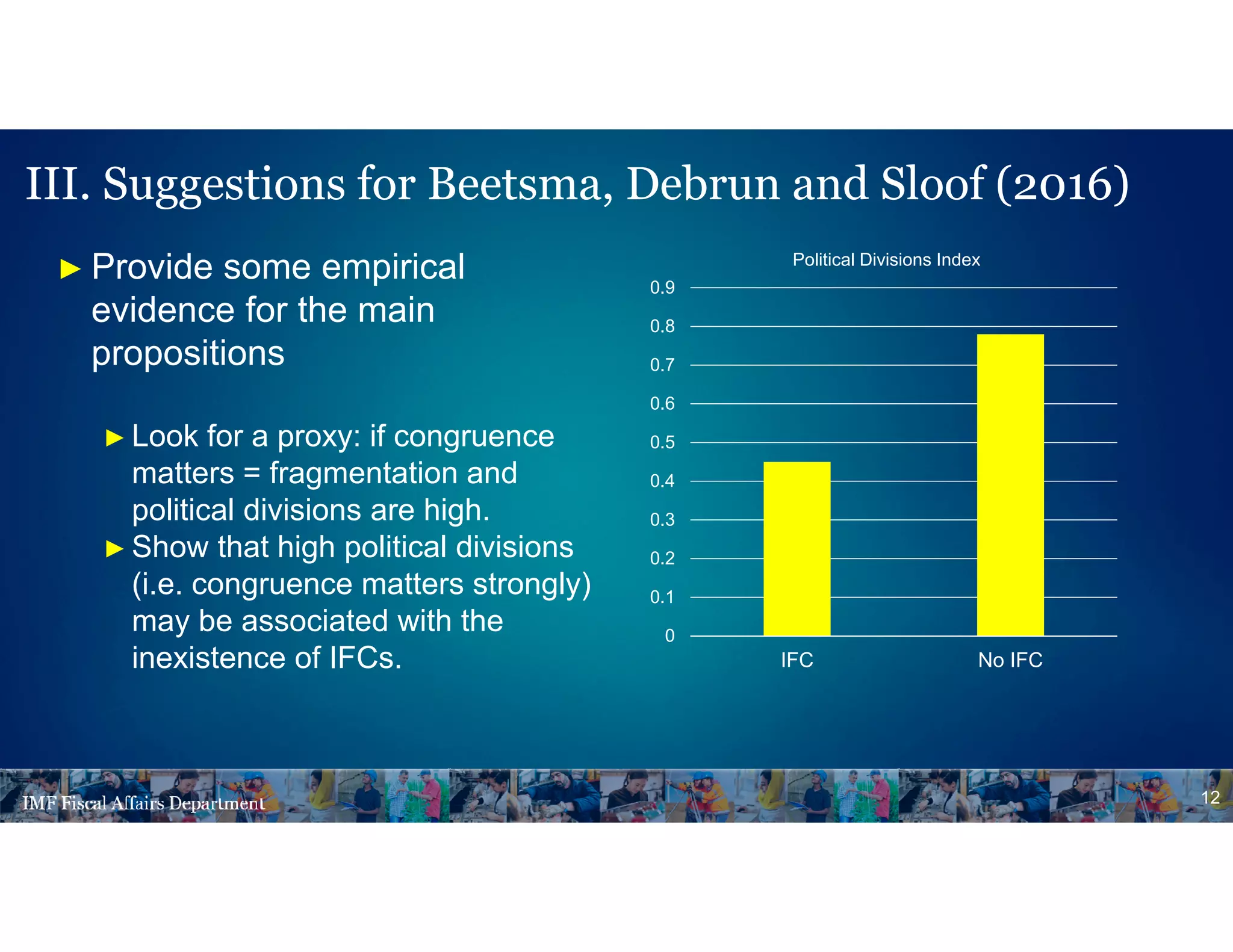

Independent fiscal councils have proliferated in recent years to promote fiscal discipline. However, their effects are shaped by political conditions. Elections, political fragmentation, and ideology all influence fiscal outcomes. When political divisions are high, incumbents may choose not to create independent fiscal councils since they reduce congruence with voters' preferences. The document suggests empirical tests could provide evidence on when and how political factors determine the establishment and impact of independent fiscal councils.