This document is a capstone thesis submitted by Stephanie Del Valle to New Jersey City University in partial fulfillment of an MBA degree. The thesis investigates the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance through an empirical study of Coca-Cola and Microsoft. The thesis acknowledges those who supported the author's work. It then provides an abstract that outlines the purpose of studying the relationship between CSR and financial performance, which some previous studies have found to be positive, negative, or nonexistent. The thesis proposes using CSR ratings and various financial metrics as dependent and independent variables for empirical testing. It concludes that differences in financial performance did not impact CSR ratings for Coca-Cola and Microsoft, indicating no direct

![AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

45

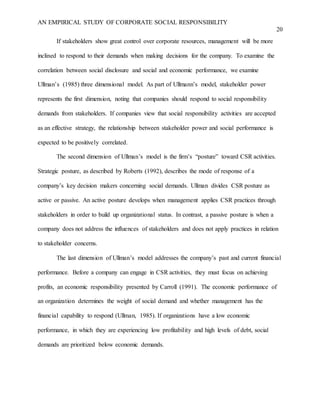

The second observation compares the P-value and α. The P-value indicates a probability

from 0 to 1. The P-value number represents P[ F > F crit] = 0.954858983. If P-value is less than

α, the significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected. In this case, the P-value is

greater than α, accepting the null hypothesis. There is a 95.48% chance of observing a difference

between sample means as large as observed even if the population means are identical.

Through both observations, it is concluded that average financials in each year are the

same between firms.

Table 4 represents the results for Anova single factor for Coca Cola for the years 2013-

Table 4.Coca-Cola Anova Single Factor significance *(0.05) **(0.01) ***(0.001)

In this observation, upon comparing the F value to F crit value, we also accept the null

hypothesis, since F value (0.000406332) is less than the F crit value (3.68232). Upon comparing

the P-value and α. We also accept the null hypothesis, since the P-value (0.999593761) is greater

than α (0.05). There is a 99.95% chance of observing a difference between sample means as

large as observed even if the population means are identical.

SUMMARY Coca Cola

Groups Count Sum Average Variance

2015 6 187537.4 31256.22821 1425472895

2014 6 191144.3 31857.38521 1431163758

2013 6 188694.4 31449.05901 1317067611

ANOVA

Source of Variation SS df MS F P-value F crit

Between Groups 1130607.464 2 565303.7321 0.000406332*** 0.999593761 3.68232

Within Groups 20868521322 15 1391234755

Total 20869651929 17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1bb4fb3f-a29d-4a4f-80bd-c29989583435-160722202810/85/Capstone-Thesis-45-320.jpg)