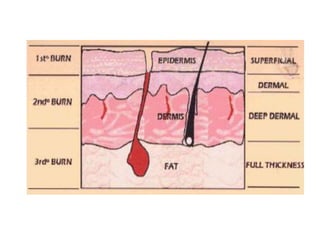

This document provides an overview of burn management, including the pathophysiology and systemic effects of major burns involving over 20% of total body surface area. Major burns can cause fluid shifts, hemodynamic changes, increased metabolic demands, renal issues, pulmonary impacts, hematological changes, immunological effects, and gastrointestinal problems. The severity of burns is determined by depth, extent of total body surface area affected, age, location on the body, medical history, and presence of inhalation injury. Patients with over 10% TBSA burns, young children, and those with full thickness or circumferential burns often require hospitalization.