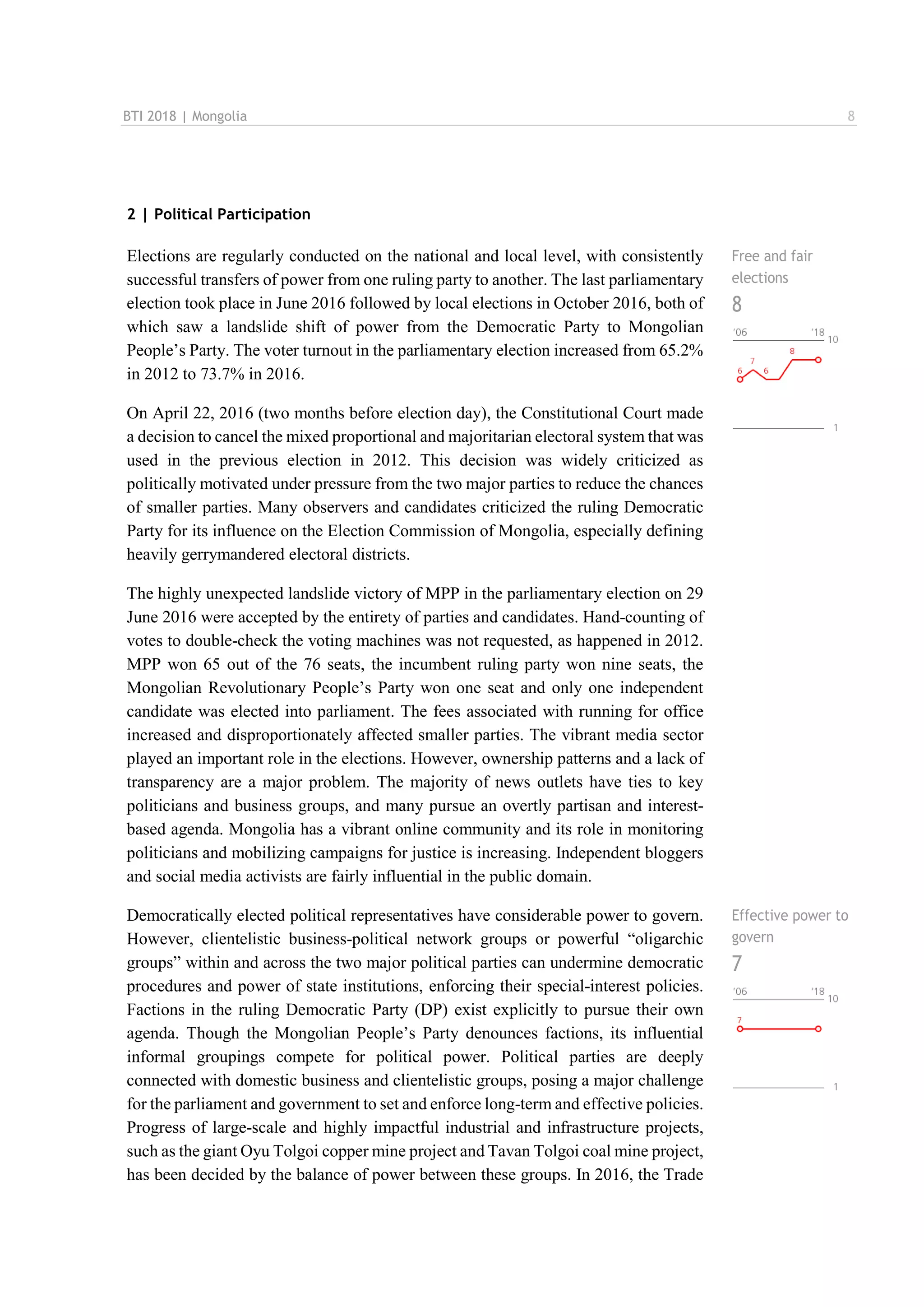

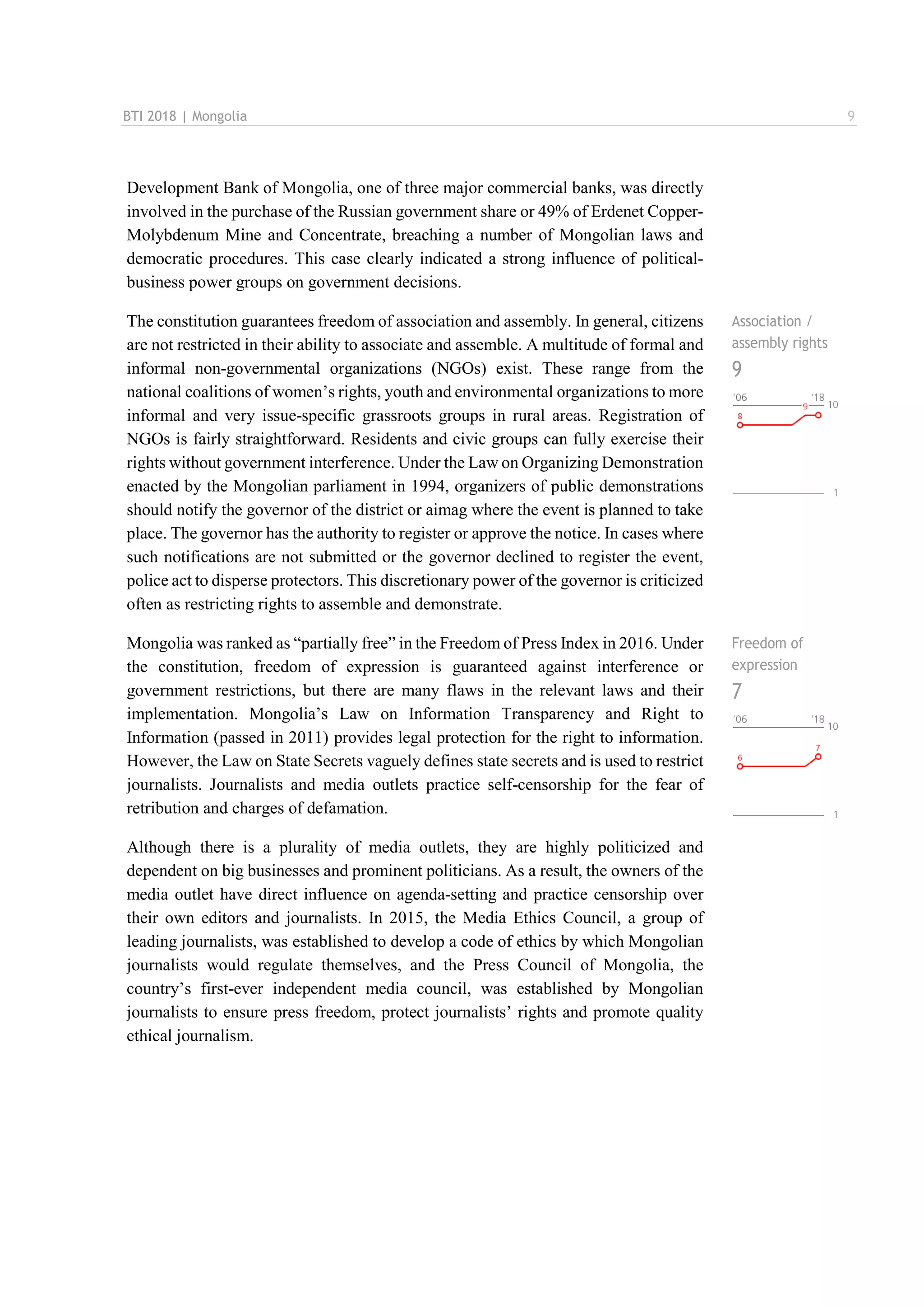

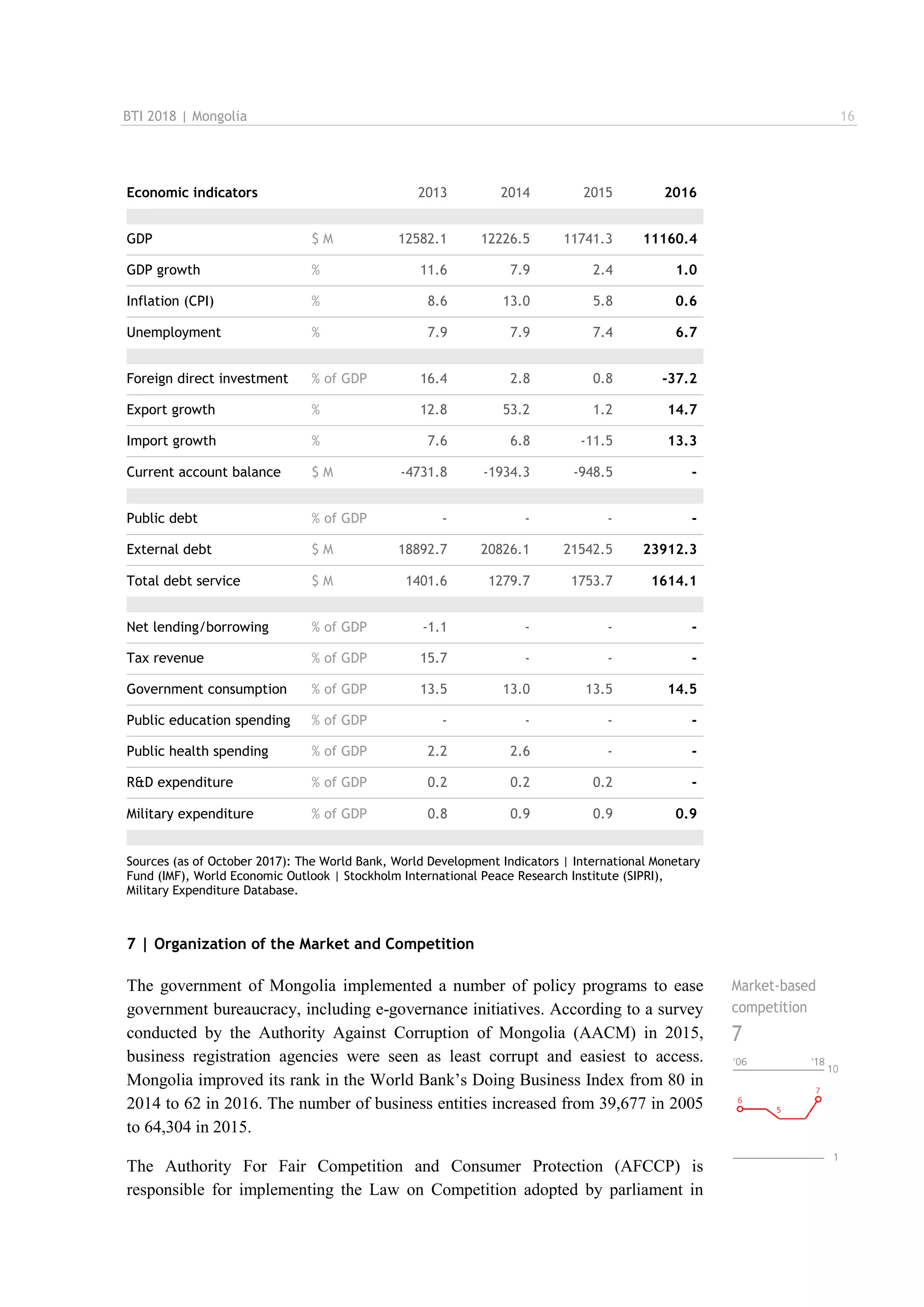

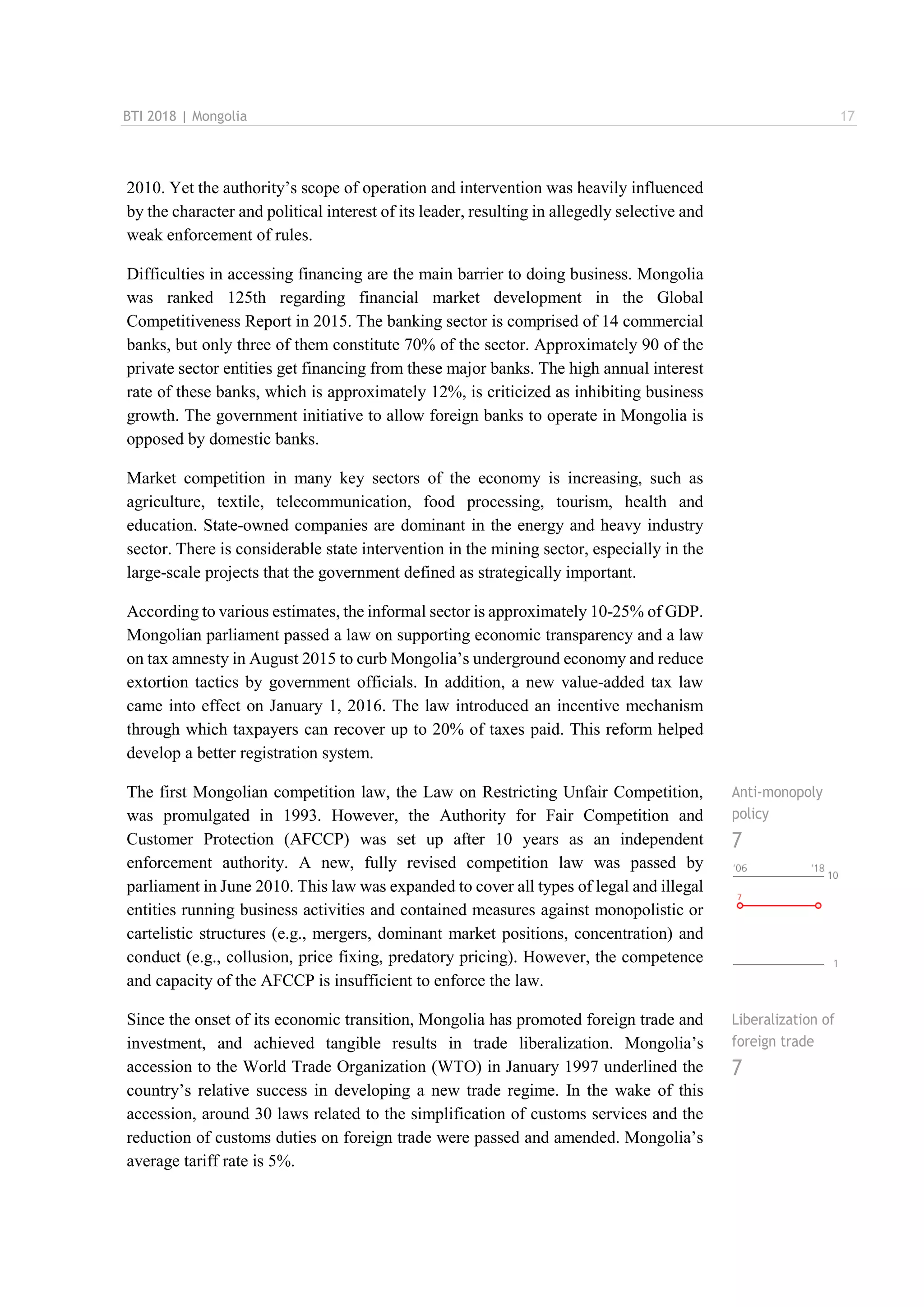

The BTI 2018 report on Mongolia covers the country's political and economic transformation, highlighting the significant decline in economic growth after the end of the mining boom in 2013, with GDP growth slowing to 1% in 2016. The report details increased government spending and a high budget deficit, alongside political shifts following the 2016 elections, which saw the Mongolian People’s Party gain significant power. Despite democratic procedures being in place, entrenched corruption and clientelism challenge the integrity and functionality of the political system.