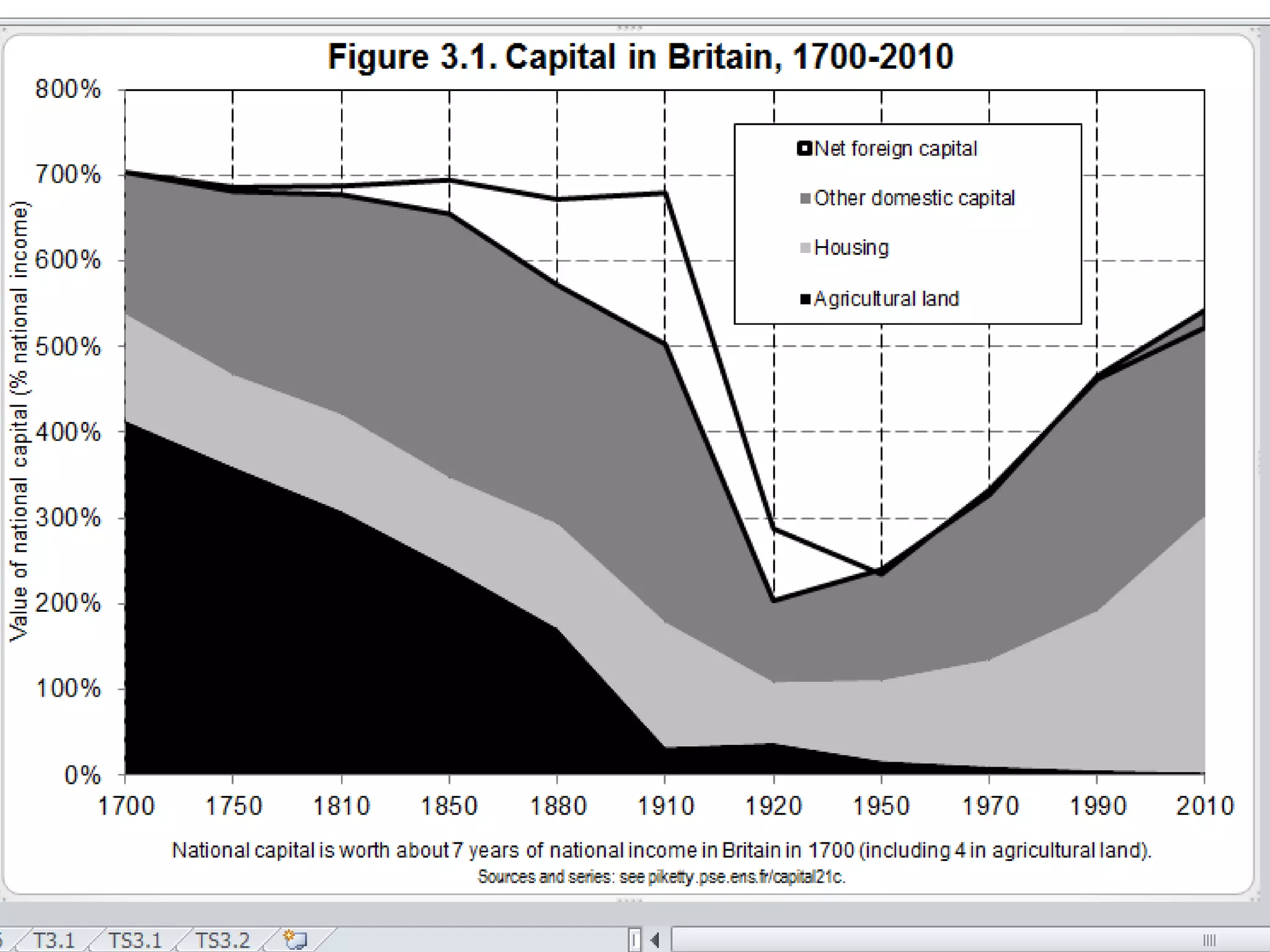

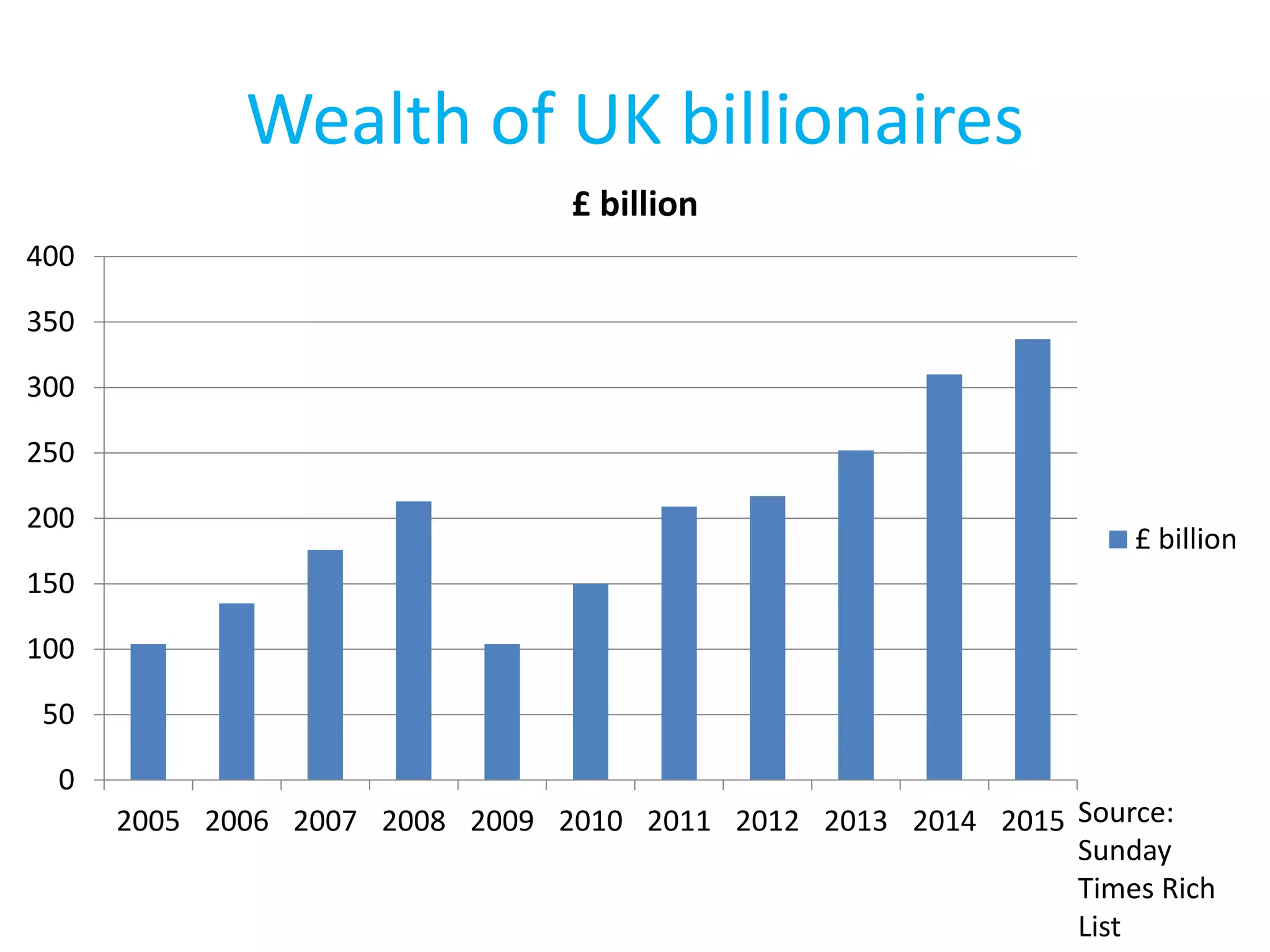

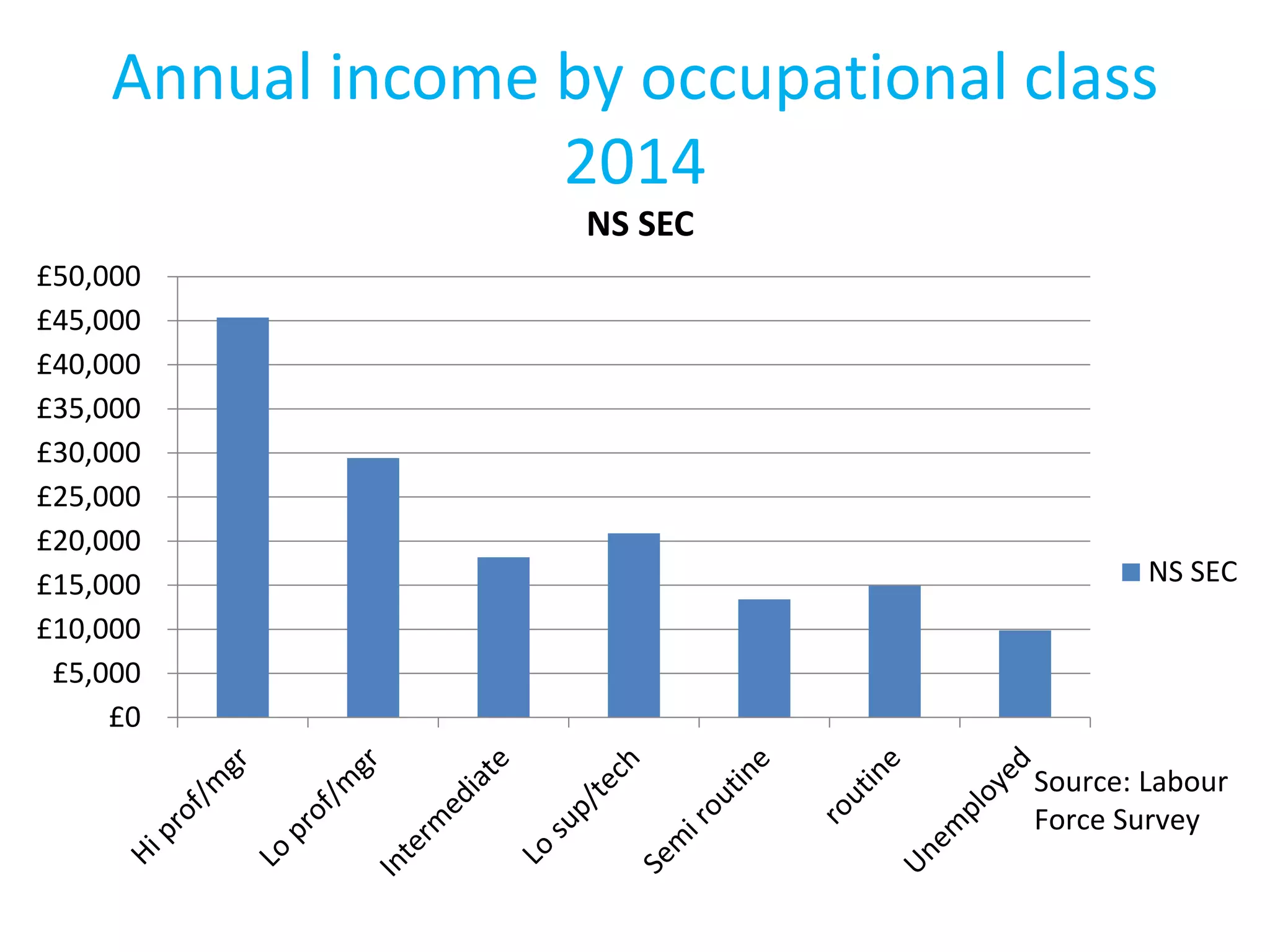

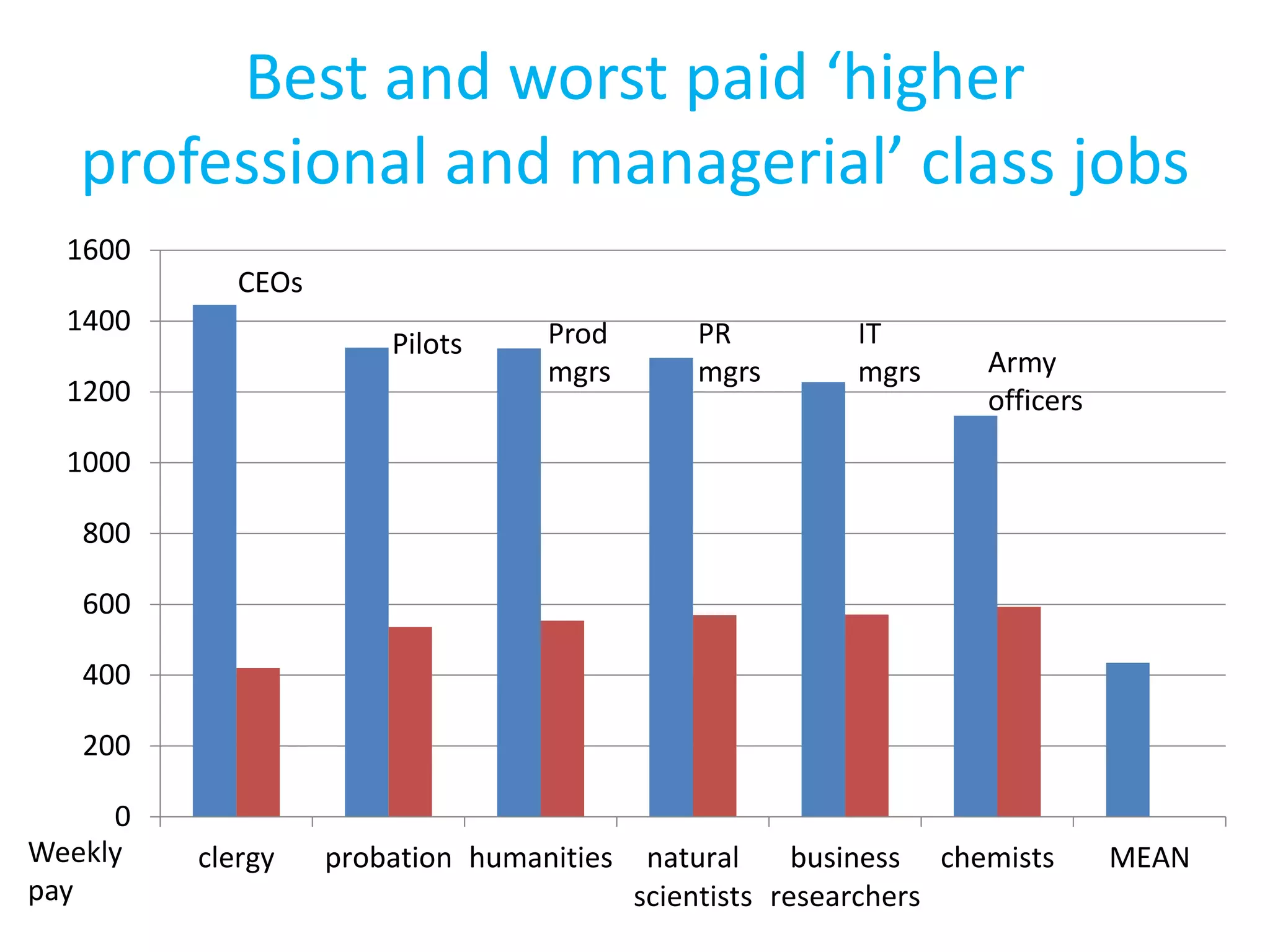

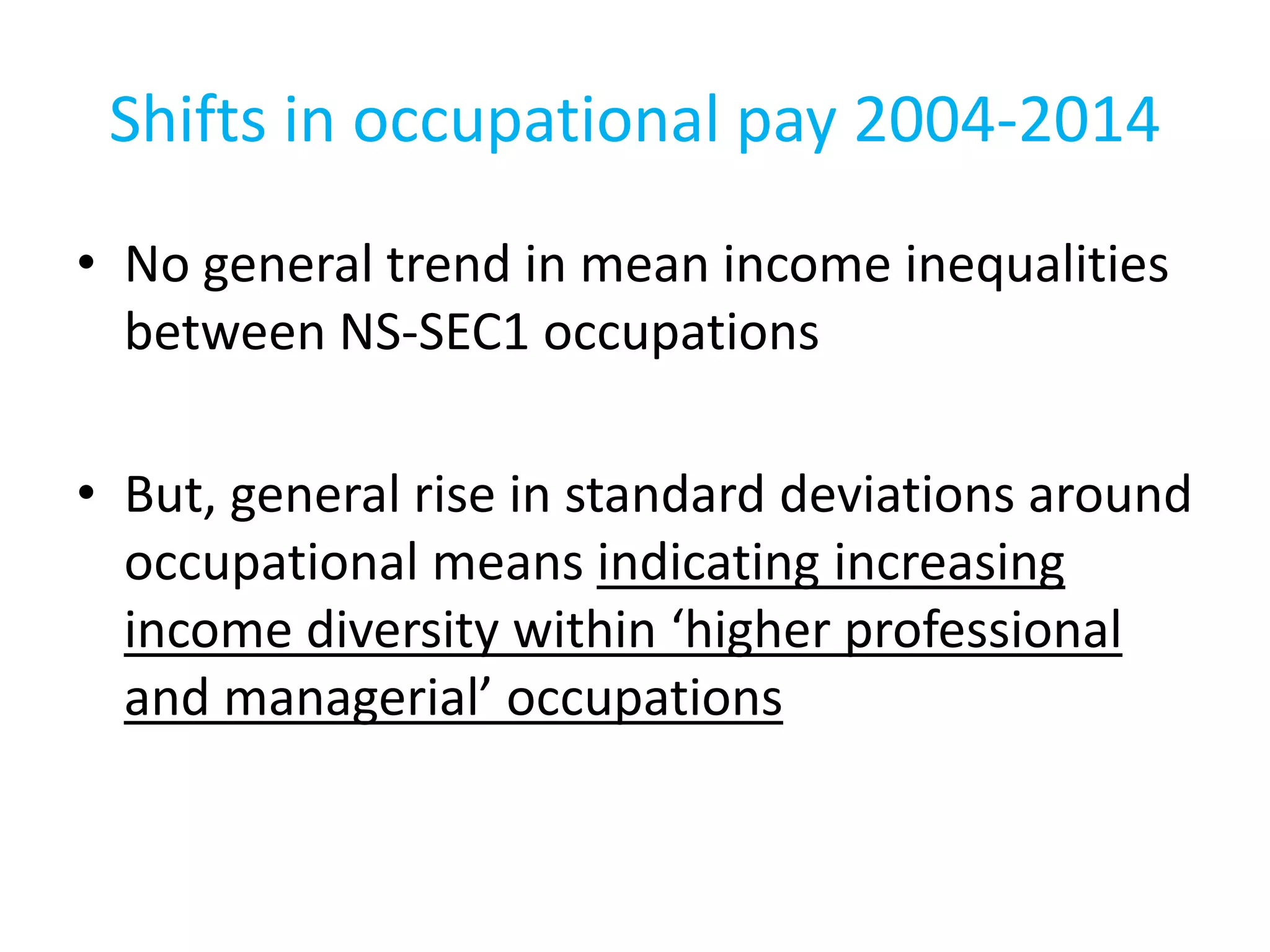

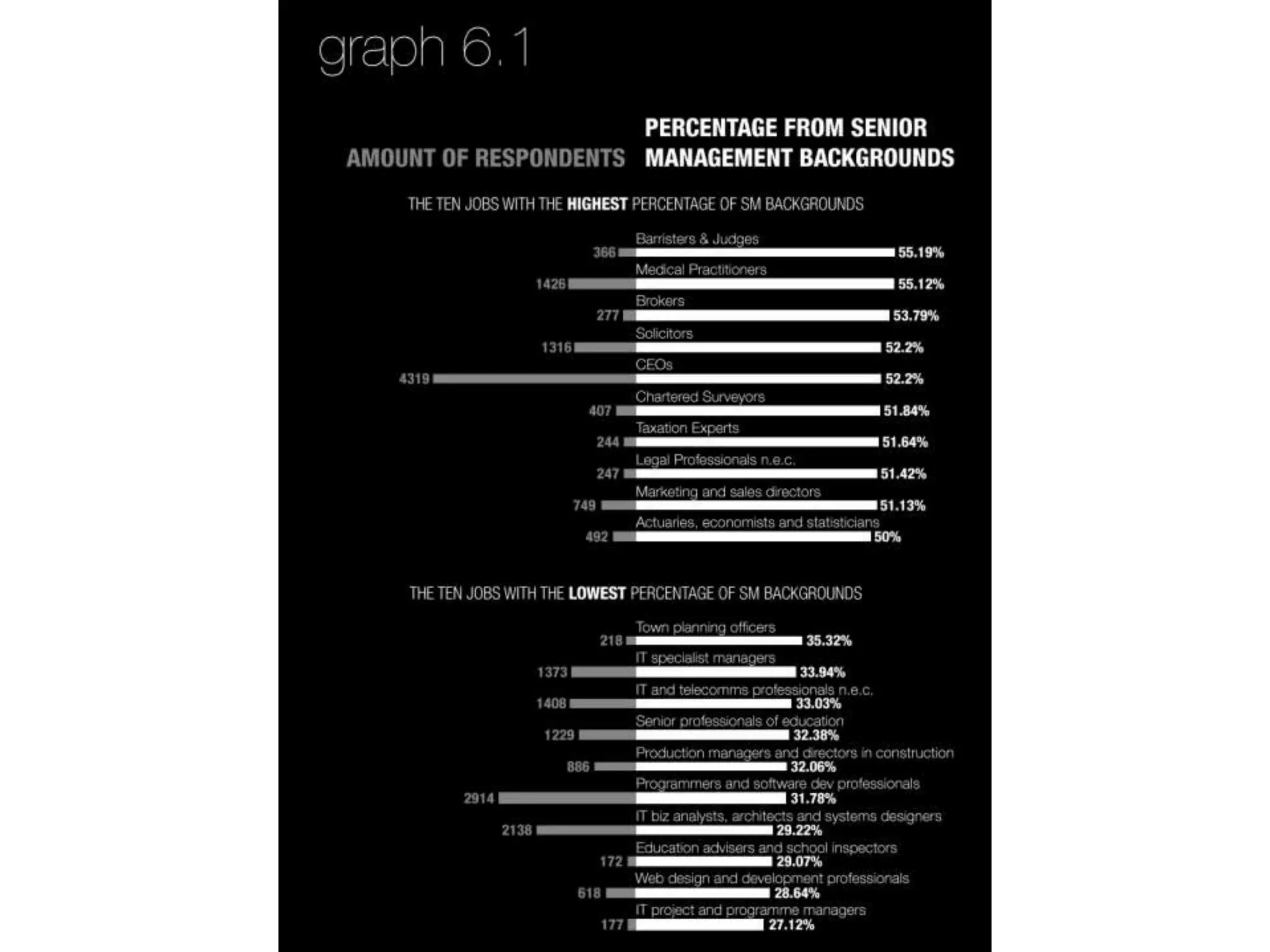

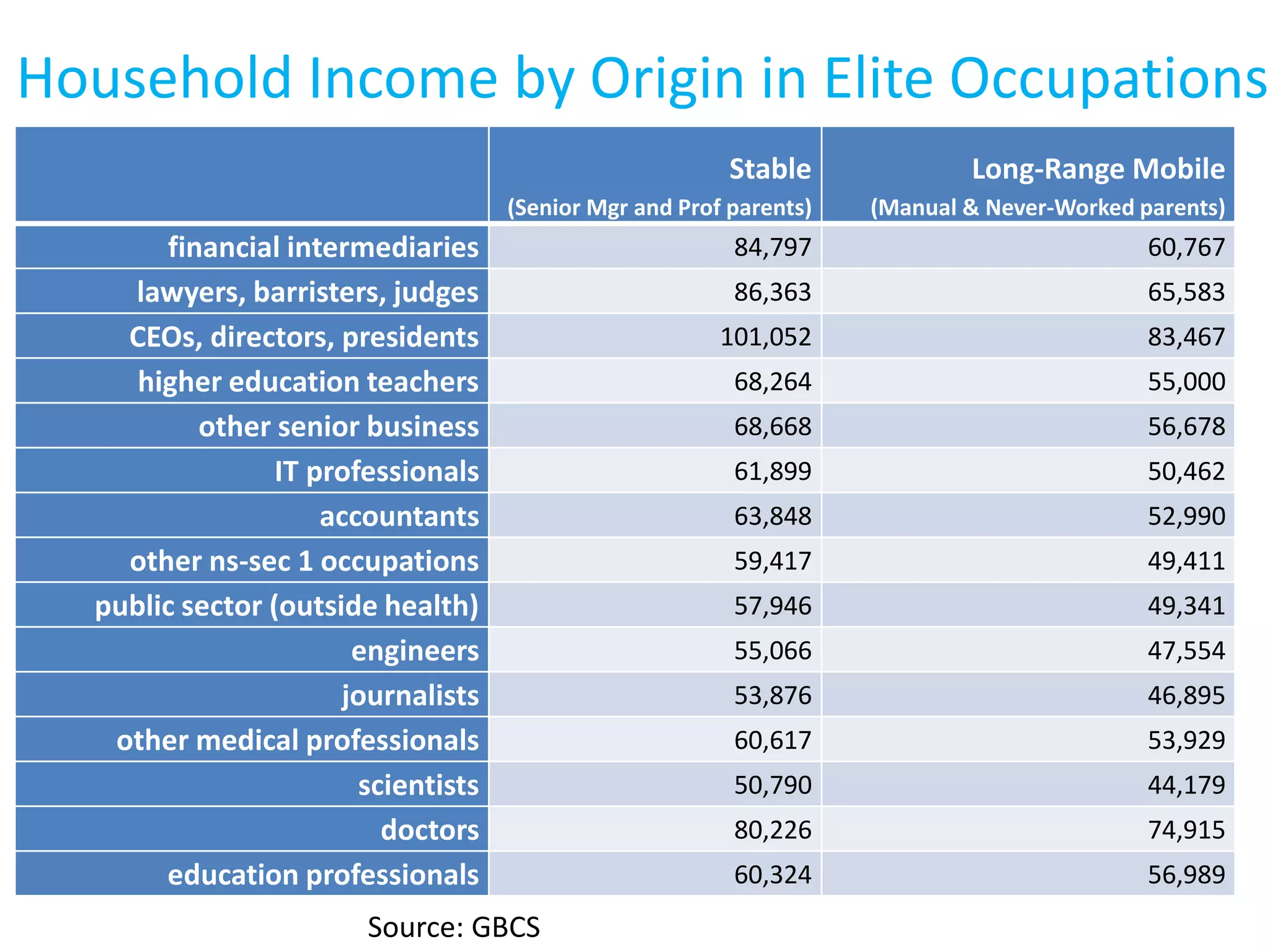

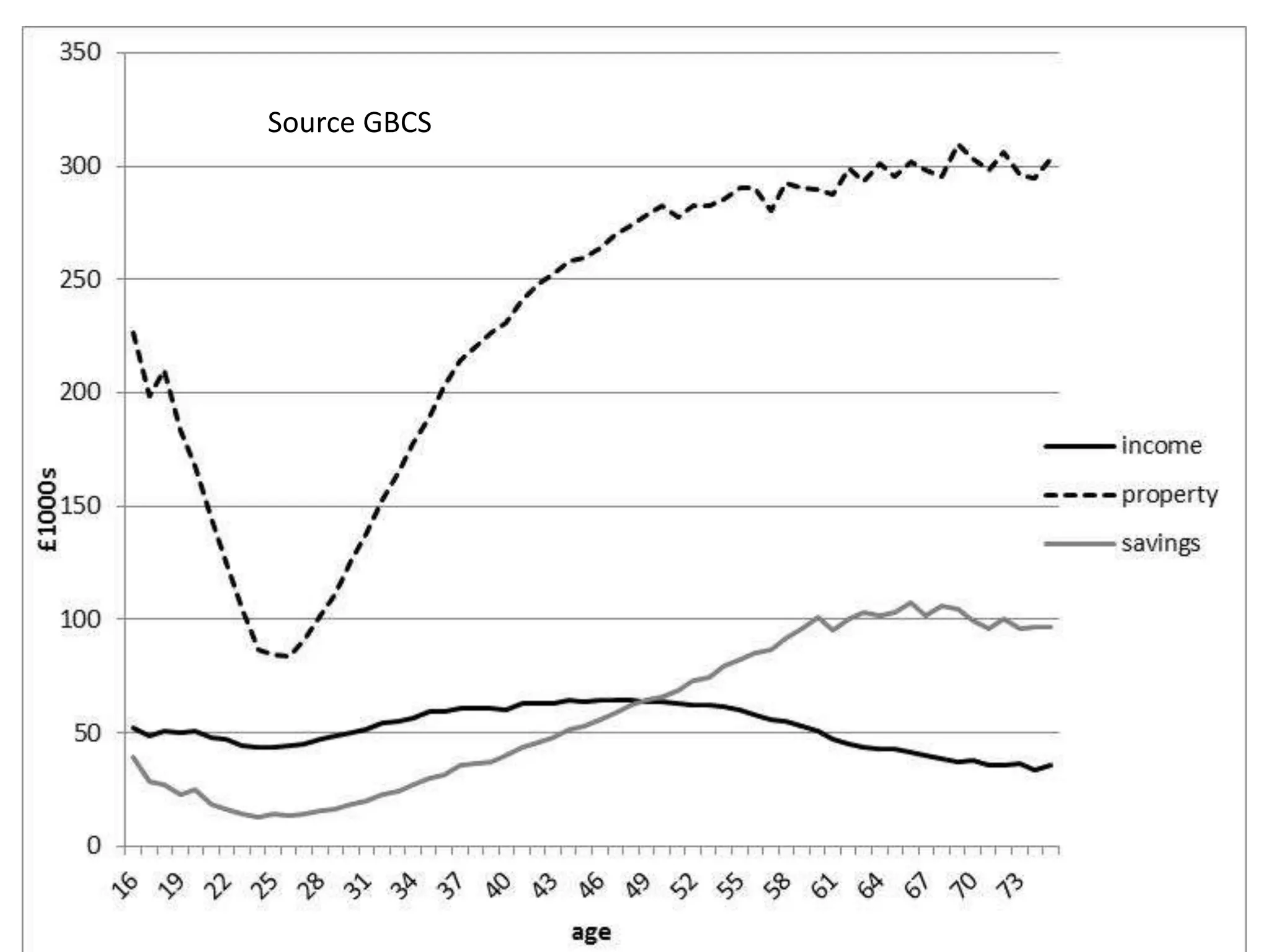

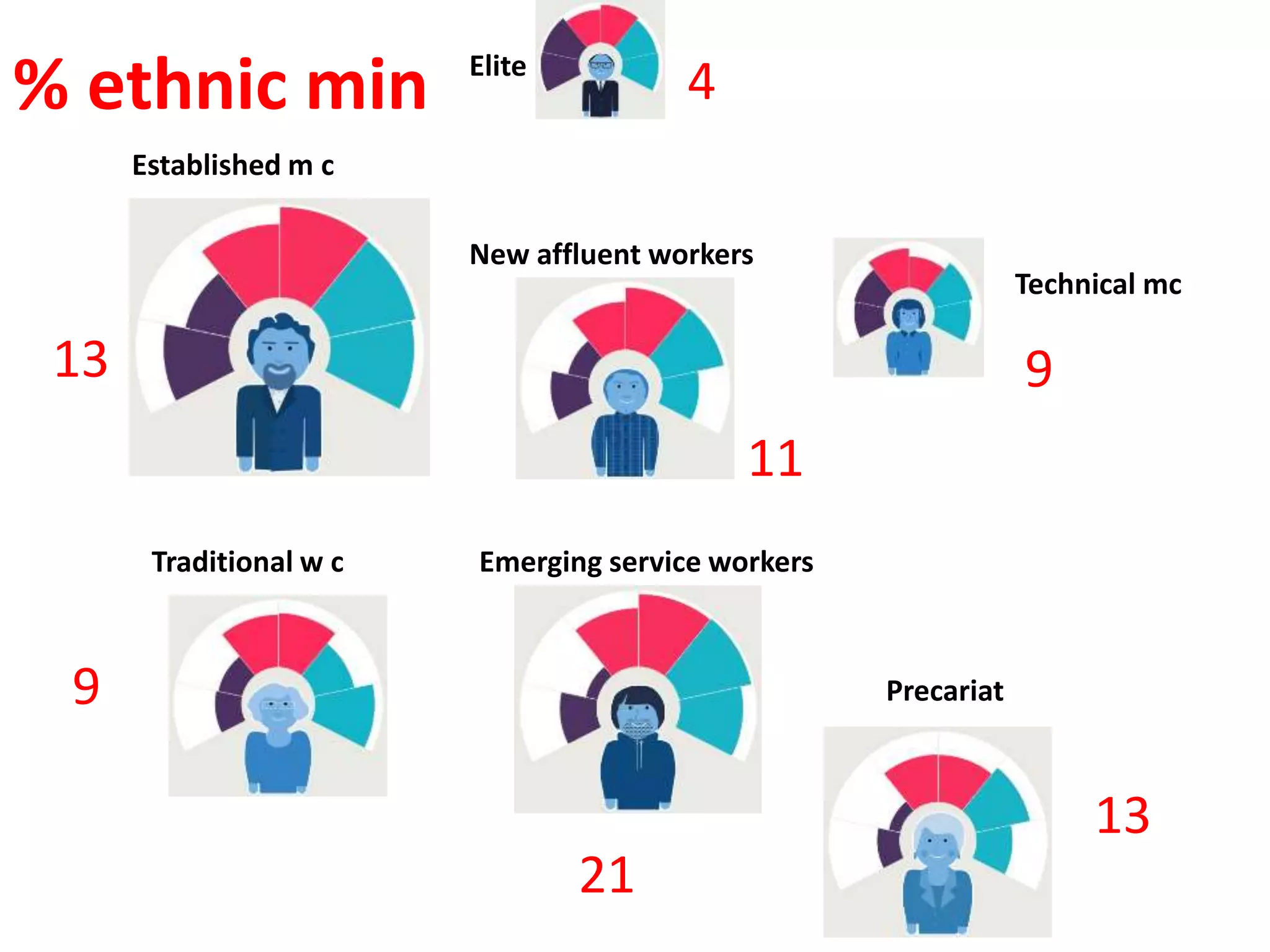

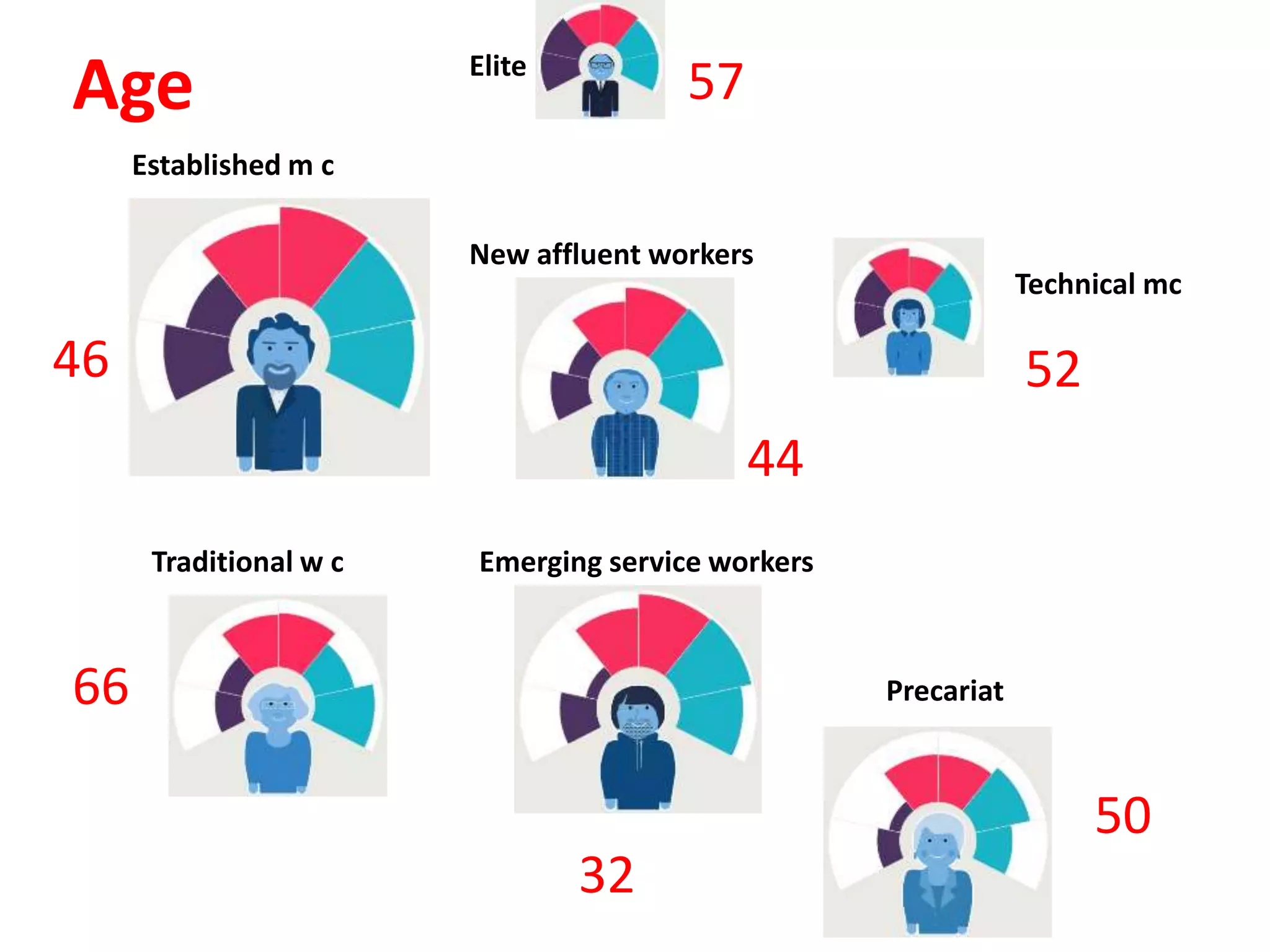

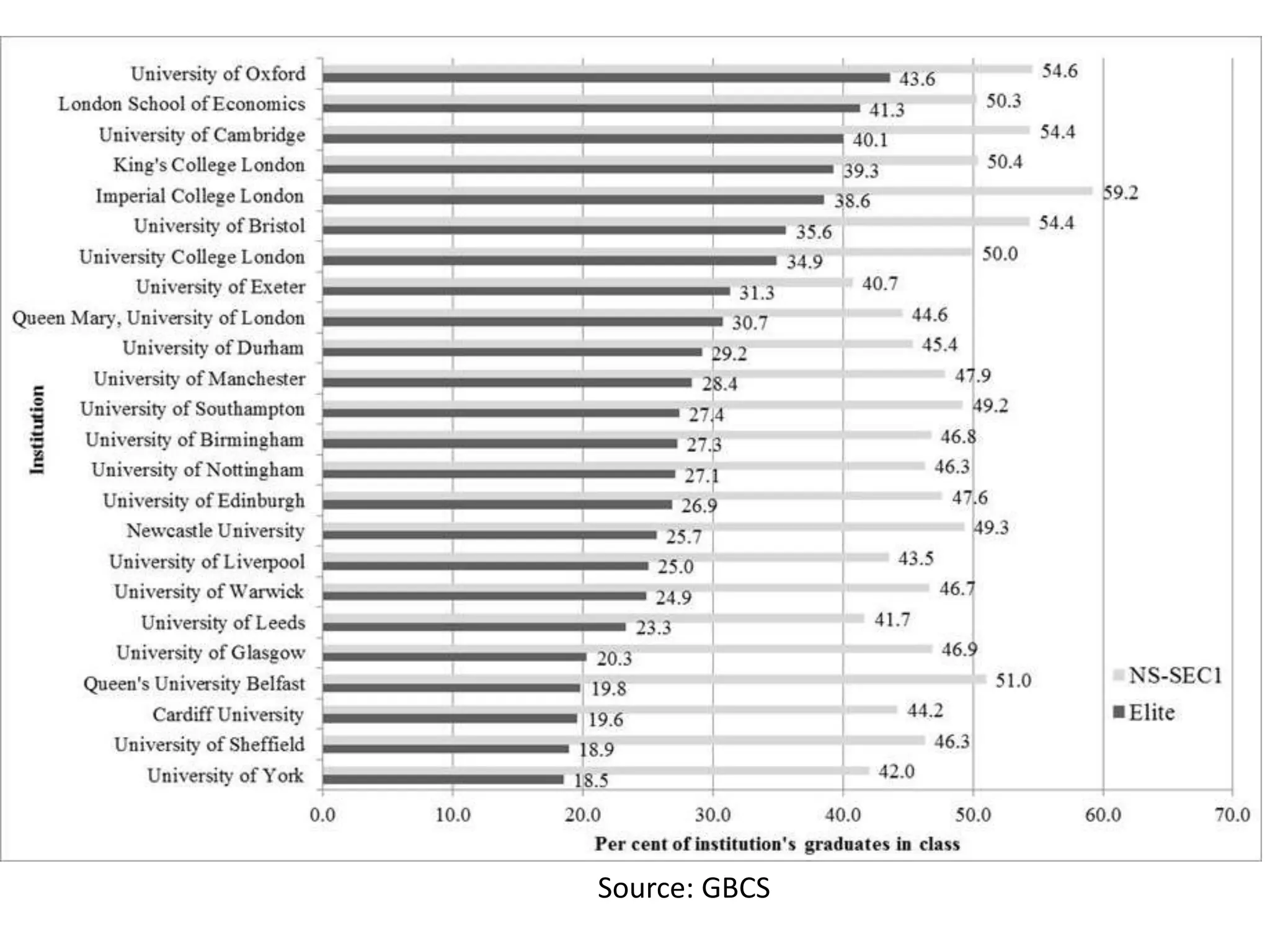

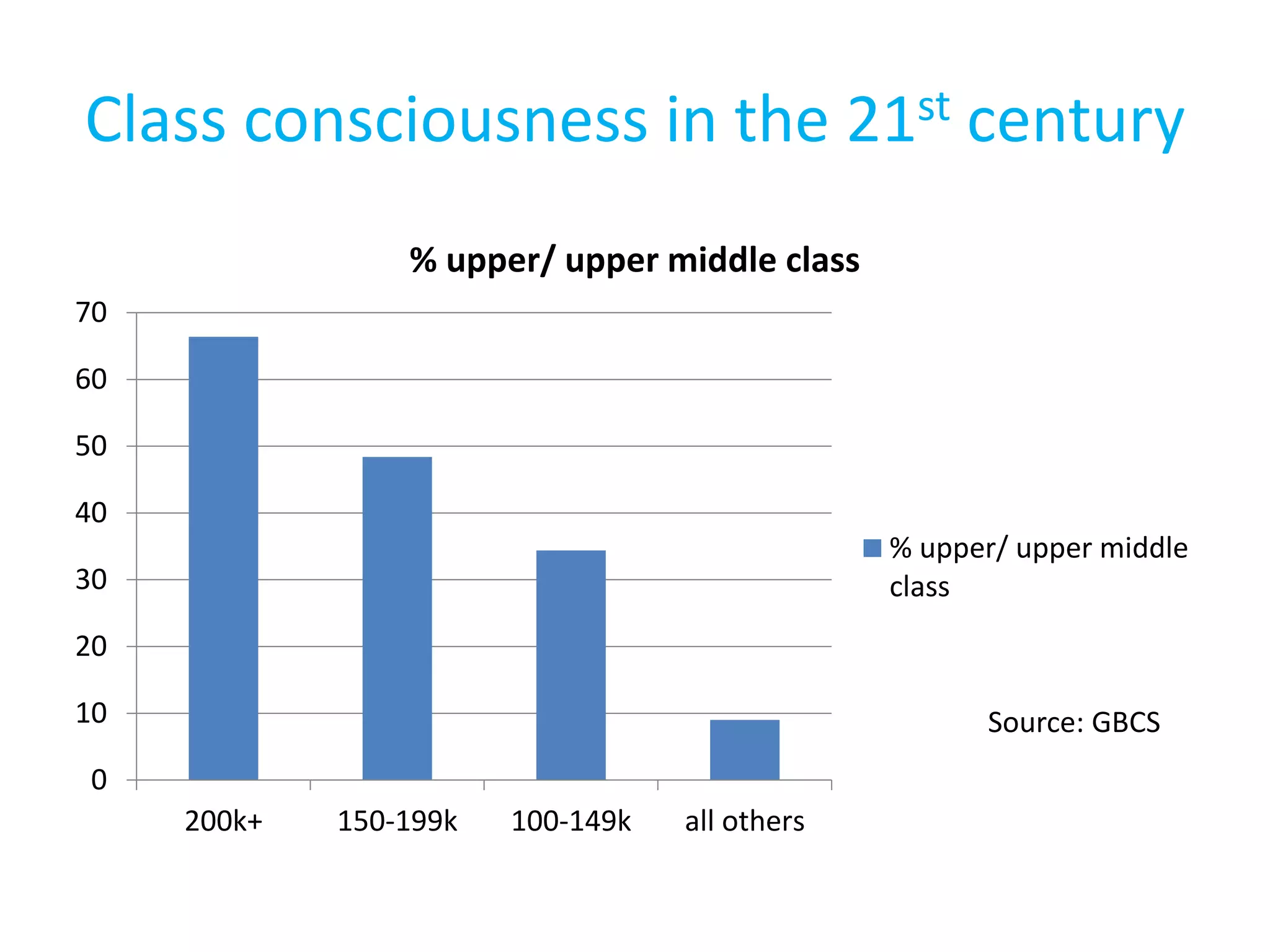

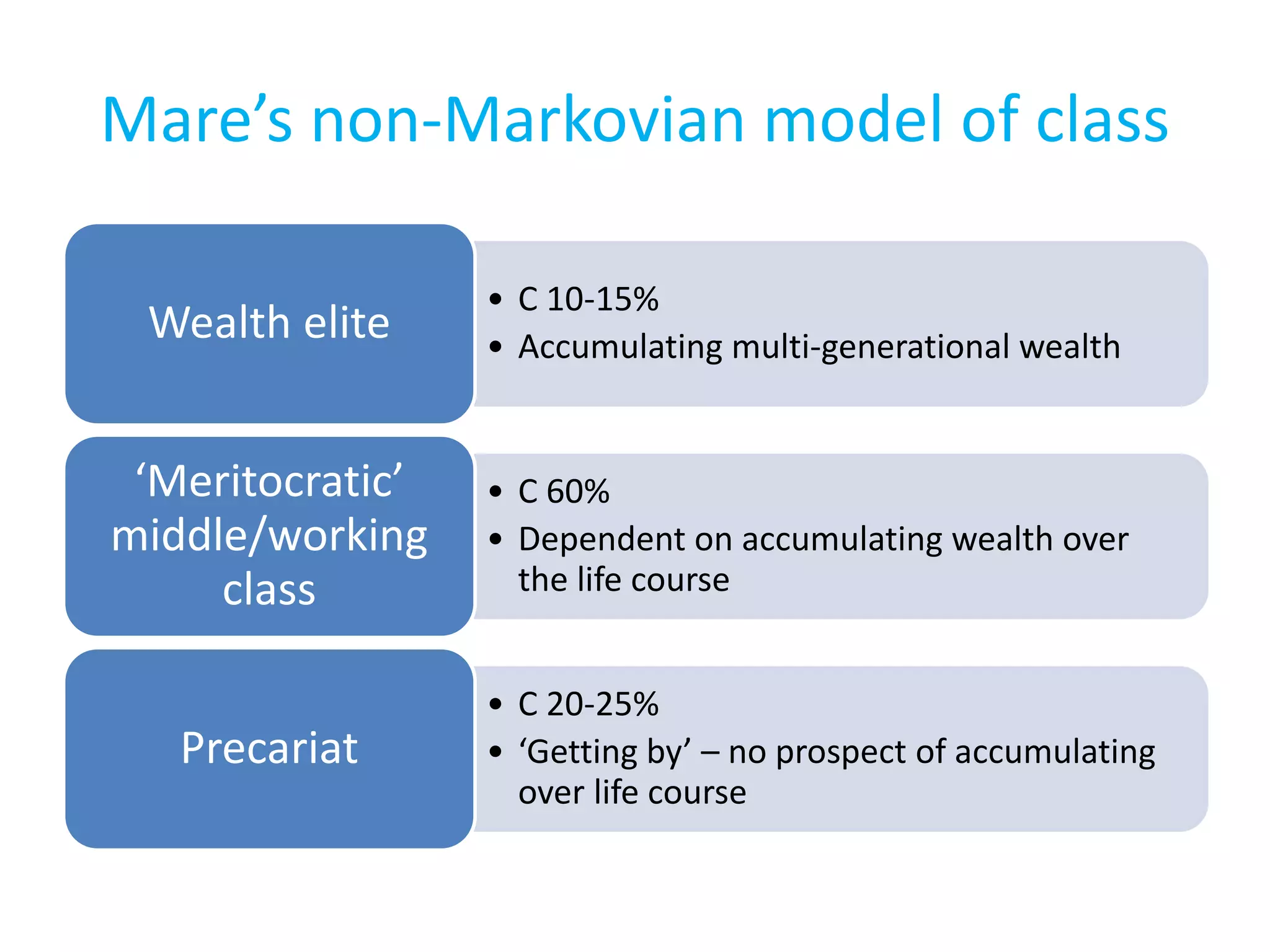

The document discusses the evolving nature of social class in 21st century Britain, emphasizing that traditional class divisions are fading while discussions around wealth accumulation and inheritance are becoming more significant. It critiques the inadequacy of occupational models in addressing economic inequalities and highlights the increasing influence of elite advantages, referred to as 'Matthew effects'. The conclusion suggests a shift in focus from the middle-working class divide to understanding patterns of wealth accumulation and the implications of rising economic inequality.