The document outlines instructions for a research paper assignment focused on self-management in organizational behavior. Students are to discuss the significance of a previously approved scholarly article, analyze their own organizational problems using a problem-solving framework, and provide recommendations based on their findings. Additionally, it includes guidelines for formatting, structuring the paper, and incorporating personal personality assessments related to teamwork dynamics.

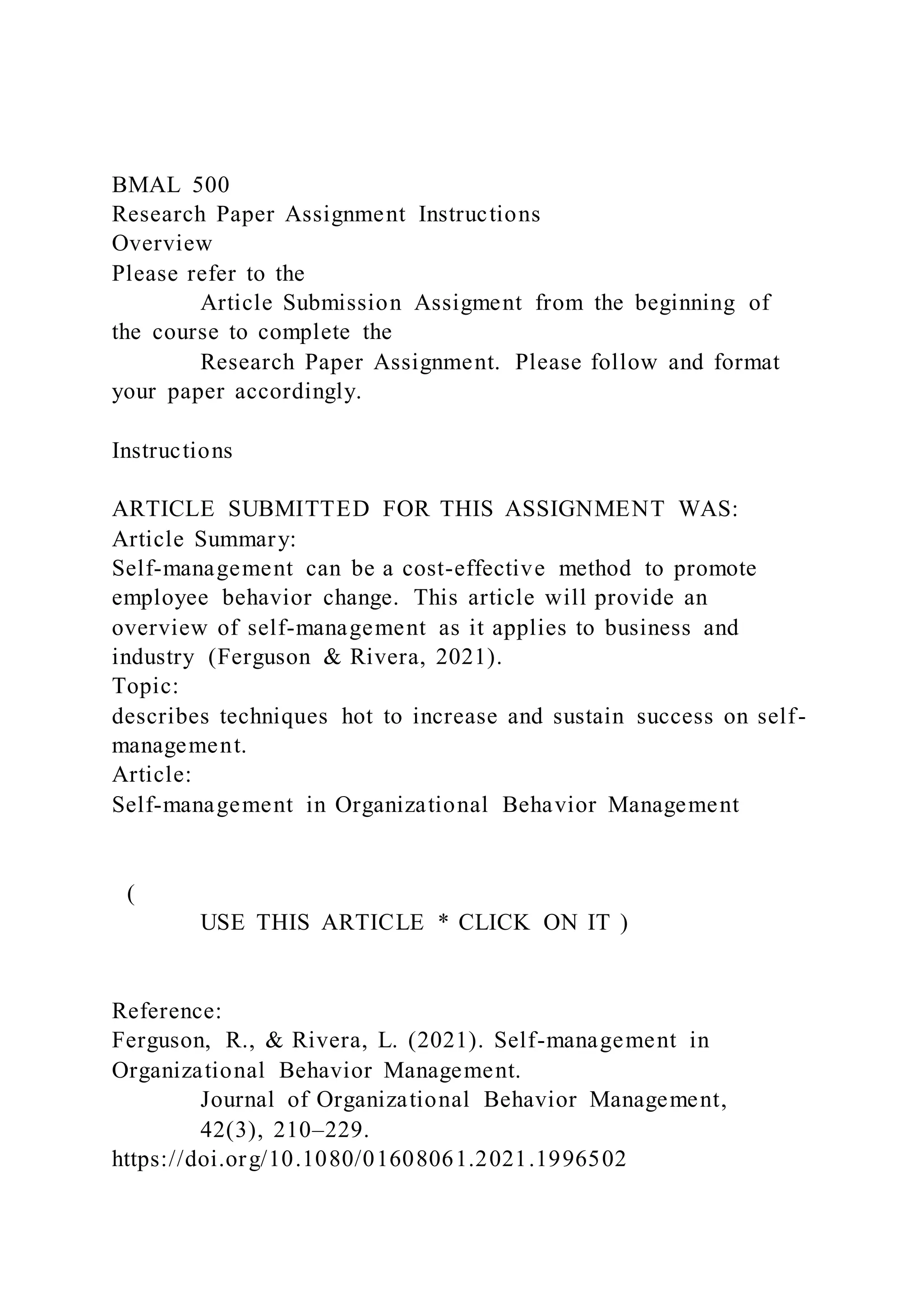

![Created by Christy Owen of Liberty University’s Online

Writing Center

[email protected]; last date modified: November 7, 2021

Sample APA Paper: Professional Format for Graduate/Doctoral

Students

Claudia S. Sample

School of Behavioral Sciences, Liberty University

Author Note

Claudia S. Sample (usually only included if author has an

ORCID number)

I have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Claudia S. Sample.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-14-2048.jpg)

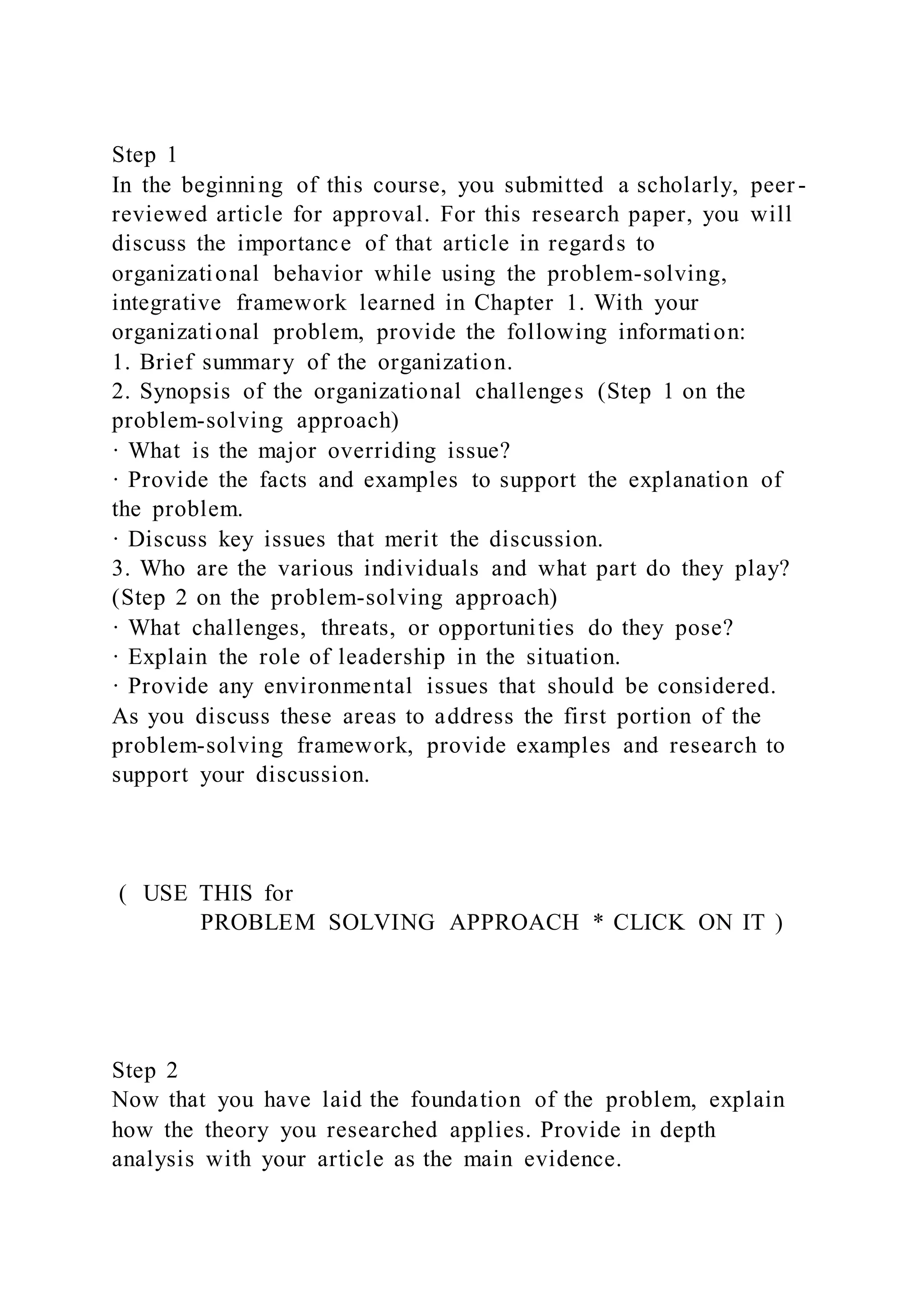

![Email: [email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE/DOCTORAL

STUDENTS 2

Table of Contents

(Only Included for Easy Navigation; Hyperlinked for Quick

Access)

Sample APA Paper: Professional Format for Graduate/Doctoral

Students .................................... 6

Basic Rules of Scholarly Writing

...............................................................................................

.... 7

Brief Summary of Changes in APA-7

.............................................................................................

8

Running Head, Author Note, and Abstract

..................................................................................... 9

Basic Formatting Elements

...............................................................................................

............ 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-15-2048.jpg)

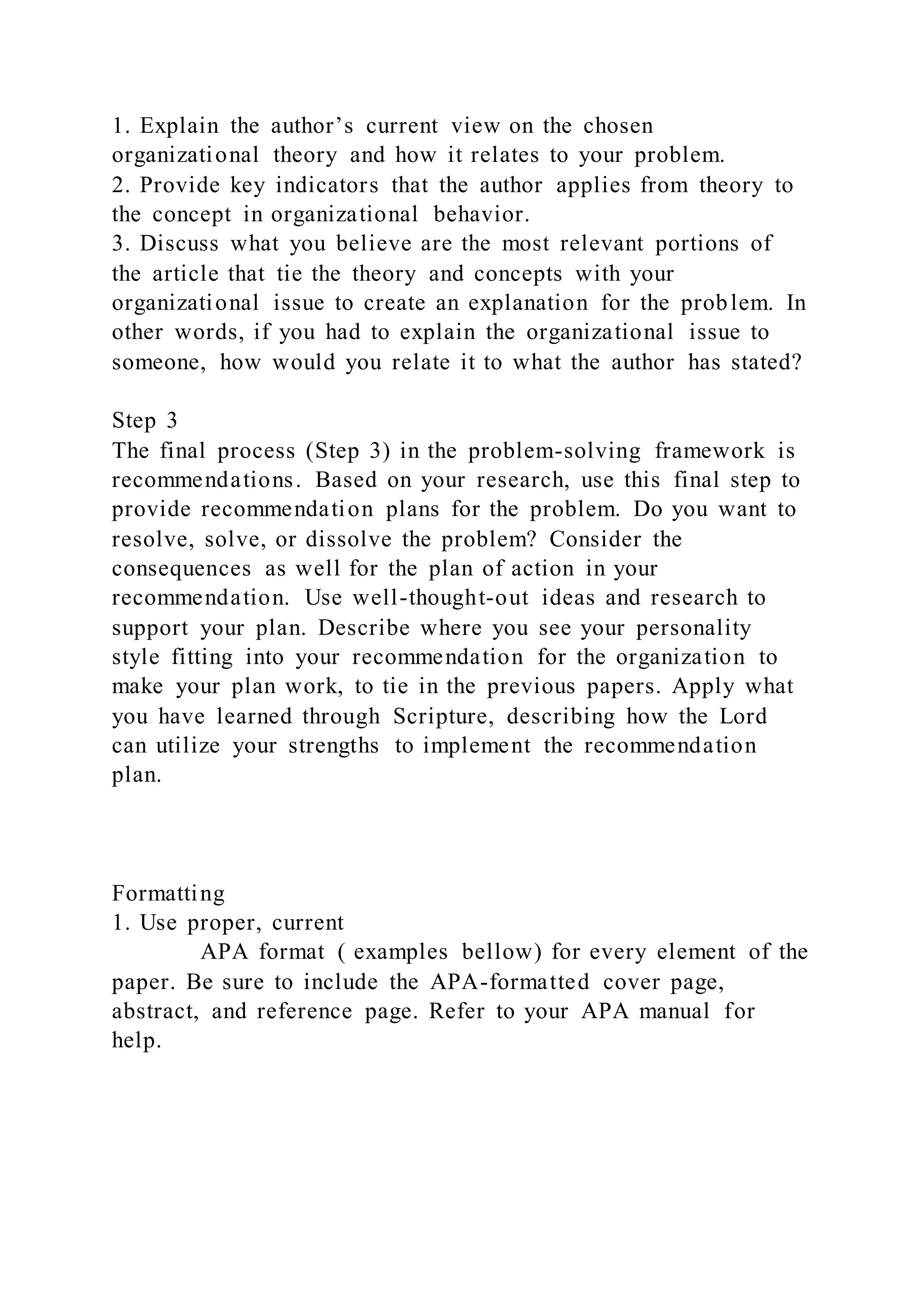

![the body (American

Psychological Association [APA], 2019, section 2.11). It should

be centered, bolded, and in title

case (all major words—usually those with four+ letters—should

begin with a capital letter)—see

p. 51 of your Publication Manual of the American Psychological

Association: Seventh Edition

(APA, 2019; hereinafter APA-7). It must match the title that is

on your title page (see last line on

p. 32). As shown in the previous sentence, use brackets to

denote an abbreviation within

parentheses (bottom of p. 159). Write out the full name of an

entity or term the first time

mentioned before using its acronym (see citation in first

sentence in this paragraph), and then use

the acronym throughout the body of the paper (section 6.25).

There are many changes in APA-7. One to mention here is that

APA-7 allows writers to

include subheadings within the introductory section (APA,

2019, p. 47). Since APA-7 now

regards the title, abstract, and term “References” to all be

Level-1 headings, a writer who opts to

include headings in his or her introduction must begin with

Level-2 headings as shown above](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-23-2048.jpg)

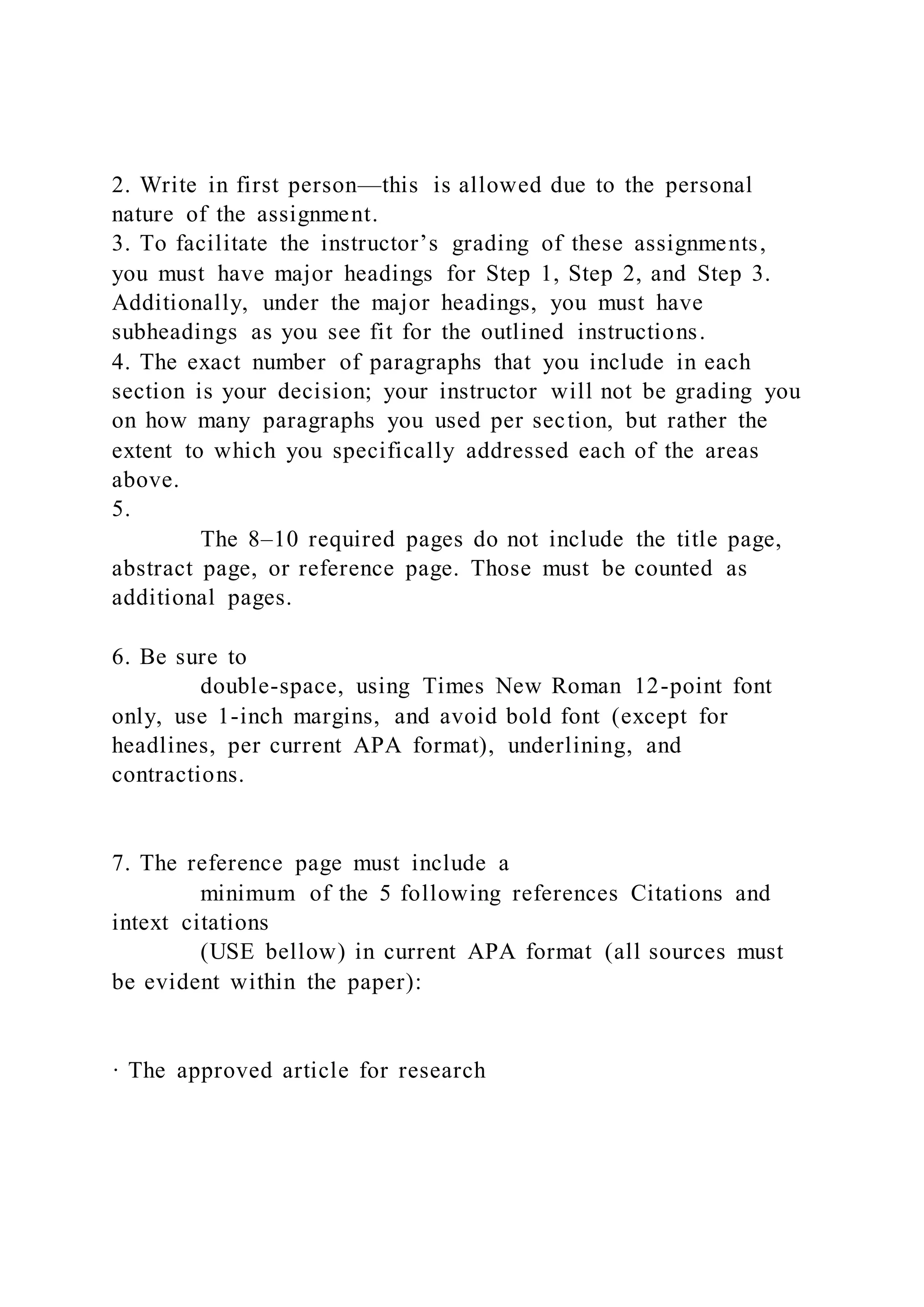

![STUDENTS 18

APA-7 now invites writers to prioritize or highlight one or more

sources as most prominent or

relevant for that content by placing “those citations first within

parentheses in alphabetical order

and then insert[ing] a semicolon and a phrase, such as ‘see

also,’ before the first of the remaining

citations” (APA., 2019, p. 263)—i.e., (Cable, 2013; see also

Avramova, 2019; De Vries et al.,

2013; Fried & Polyakova, 2018). Periods are placed after the

closing parenthesis, except with

indented (blocked) quotes.

Two Works by the Same Author in the Same Year

Authors with more than one work published in the same year are

distinguished by lower-

case letters after the years, beginning with a (APA, 2019,

section 8.19). For example, Double

(2008a) and Double (2008b) would refer to resources by the

same author published in 2008.

When a resource has no date, use the term n.d. followed by a

dash and the lowercase letter (i.e.,

Carlisle, n.d.-a and Carlisle, n.d.-b; see APA, 2019, section](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-47-2048.jpg)

![14 Chapter in an edited book with DOI.

15 Resources by two authors with the same last name but

different first names in the same year of

publication. Arrange alphabetically by the first initials.

http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/03/health/respect-toward-elderly-

leads-to-long-life-intl/index.html

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/03/health/respect-toward-elderly-

leads-to-long-life-intl/index.html

https://doi.org/10.1037/0000119-012

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615800802638279

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 32

Cable, D. (2013). The racial dot map [Map]. University of

Virginia, Weldon Cooper Center for

Public Service. https://demographics.coopercenter.org/Racial-

Dot-Map 16

Canan, E., & Vasilev, J. (2019, May 22). [Lecture notes on

resource allocation]. Department of

Management Control and Information Systems, University of

Chile. https:// uchilefau.

academia.edu/ElseZCanan 17

Carlisle, M. A. (n.d.-a). Erin and the perfect pitch. Journal of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-75-2048.jpg)

![17 PowerPoint slides or lecture notes.

18 Online journal article with a URL and no DOI; also depicts

one of two resources by the same

author with no known publication date.

19 Webpage on a website with a group author.

20 Journal article with a DOI, combination of individual and

group authors.

21 Two resources by same author in the same year. Arrange

alphabetically by the title and then

add lowercase letters (a and b, respectively here) to the year.

https://demographics.coopercenter.org/Racial-Dot-Map

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.07.007

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 33

Fistek, A., Jester, E., & Sonnenberg, K. (2017, July 12-15).

Everybody’s got a little music in

them: Using music therapy to connect, engage, and motivate

[Conference session].

Autism Society National Conference, Milwaukee, WI, United

States.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-77-2048.jpg)

![https://asa.confex.com/asa/2017/webprogramarchives/Session95

17.html 22

Forman, M. (Director). (1975). One flew over the cuckoo’s nest

[Film]. United Artists. 23

Fried, D., & Polyakova, A. (2018). Democratic defense against

disinformation. Atlantic Council.

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-

reports/report/democratic-defense-

against-disinformation/ 24

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., & Heatherton, L. (2002). E-

SOFTA: System for observing

family therapy alliances [Software and training videos]

[Unpublished instrument].

http://www.softa-soatif.com/ 25

GDJ. (2018). Neural network deep learning prismatic [Clip art].

Openclipart.

https://openclipart.org/detail/309343/neural-network-deep-

learning-prismatic 26

Goldberg, J. F. (2018). Evaluating adverse drug effects

[Webinar]. American Psychiatric

Association.

https://education.psychiatry.org/Users/ProductDetails.aspx?

ActivityID=6172 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-78-2048.jpg)

![[Doctoral dissertation,

University of Wisconsin-Madison]. ProQuest Dissertations and

Theses Global. 33

Hutcheson, V. H. (2012). Dealing with dual differences: Social

coping strategies of gifted and

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adolescents

[Master’s thesis, The College

28 Newspaper article without DOI, from most academic

research databases or print version

29 Entry in a dictionary, thesaurus, or encyclopedia, with

individual author.

30 Online newspaper article.

31 Edited book without a DOI, from most academic research

databases or print version.

32 Book chapter, print version.

33 Doctoral dissertation, from an institutional database.

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/behaviorism

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-81-2048.jpg)

![https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 35

of William & Mary]. William & Mary Digital Archive.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd/1539272210/ 34

Kalnay, E., Kanimitsu, M., Kistler, R., Collins, W., Deaven, D.,

Gandin, L., Iredell, M., Saha, S.,

White, G., Whollen, J., Zhu, Y., Chelliah, M., Ebisuzaki, W.,

Higgins, W., Janowiak, J.,

Mo, K. C., Ropelewski, C., Wang, J., Leetmaa, A., … Joseph,

D. (1996). The

NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bulletin of the

American Meteorological

Society, 77(3), 437-471. http://doi.org/ fg6rf9 35

King James Bible. (2017). King James Bible Online.

https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/

(Original work published 1769) 36

Lewin, K. (1999). Group decision and social change. In M. Gold

(Ed.), The complex social

scientist: A Kurt Lewin reader (pp. 265-284). American](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-82-2048.jpg)

![0liberty.edu%7Cb709d48eab614c47330308d7f67e8f9c%7Cbaf8

218eb3024465a9934a39c97251b2%7C0%7C0%7C63724889575

8832975&sdata=2kfyvpGtDiu0nVnT%2Fy0%2BUXZcfAi%2FB

AadIm9QwtjT0g8%3D&reserved=0

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 36

McCauley, S. M., & Christiansen, M. H. (2019). Language

learning as language use: A cross-

linguistic model of child language development. Psychological

Review, 126(1), 1-51.

https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000126 40

McCurry, S. (1985). Afghan girl [Photograph]. National

Geographic.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/national-

geographic-magazine-50-years-

of-covers/#/ngm-1985-jun-714.jpg 41

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Heuristic. In Merriam-Webster.com

dictionary. Retrieved 01/02/2020,

from http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/heuristic 42

National Cancer Institute. (2018). Facing forward: Life after

cancer treatment (NIH Publication

No. 18-2424). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

National Institutes of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-84-2048.jpg)

![714.jpg

http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/heuristic

https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/life-

after-treatment.pdf

https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/pages/what-employers-

should-do-to-protect-rns-from-zika

https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/pages/what-employers-

should-do-to-protect-rns-from-zika

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 37

Owen, C. (2012, Spring). Behavioral issues resulting from

attachment have spiritual

implications [Unpublished manuscript]. COUN502, Liberty

University. 46

Perigogn, A. U., & Brazel, P. L. (2012). Captain of the ship. In

J. L. Auger (Ed.) Wake up in the

dark (pp. 108-121). Shawshank Publications. 47

Peters, C. (2012). COUN 506: Integration of spirituality and

counseling. Week one, lecture two:

Defining integration: Key concepts. Liberty University.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/defining-integration-key-

concepts/id427907777?i=1000092371727 48

Pew Research Center. (2018). American trend panel Wave 26

[Data set].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-86-2048.jpg)

![https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/dataset/american-trends-panel-

wave-26 49

Prayer. (2015). http:// www exact-webpage 50

Project Implicit. (n.d.). Gender–Science IAT.

https://implicit.harvard.edu/implici/take test.html 51

Schatz, B. R. (2000, November 17). Learning by text or

context? [Review of the book The social

life of information, by J. S. Brown & P. Duguid]. Science, 290,

1304.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5495.1304 52

Schmid, H.-J. (Ed.). (2017). Entrenchment and the psychology

of language learning: How we

reorganize ad adapt linguistic knowledge. American

Psychological Association; De

46 Citing a student’s paper submitted in a prior class, in order

to avoid self-plagiarism.

47 Chapter from an edited book.

48 Liberty University class lecture using course details.

49 Data set.

50 Online resource with no named author. Title of webpage is in

the author’s place.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-87-2048.jpg)

![Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2

Restructured Form (MPI-2-RF): Technical manual. Pearson. 57

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). U.S. and world population clock.

U.S. Department of Commerce.

Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/popclock

58

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2017). Agency

financial report: Fiscal year 2017.

https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2017-agency-financial-report.pdf

59

University of Oxford. (2018, December 6). How do geckos walk

on water? [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qm1xGfOZJc8 60

53 Edited book with a DOI, with multiple publishers.

54 Two resources by the same author, in different years.

Arrange by the earlier year first.

55 Shakespeare.

56 Electronic version of book chapter in a volume in a series

57 Manual for a test, scale, or inventory.

58 Webpage on a website with a retrieval date.

59 Annual report.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-89-2048.jpg)

![60 YouTube or other streaming video.

https://doi.org/10.1037/15969-000

https://doi.org/10.1037/10762-000

https://www.census.gov/popclock

https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2017-agency-financial-report.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qm1xGfOZJc8

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 39

Vedentam, S. (Host). (2015-present). Hidden brain [Audio

podcast]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/

series/423302056/hidden-brain 61

Weinstock, R., Leong, G. B., & Silva, J. A. (2003). Defining

forensic psychiatry: Roles and

responsibilities. In R. Rosner (Ed.), Principles and practice of

forensic psychiatry (2nd

ed., pp. 7-13). CRC Press. 62

Yoo, J., Miyamoto, Y., Rigotti, A., & Ryff, C. (2016). Linking

positive affect to blood lipids: A

cultural perspective [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of

Psychology, University of

Wisconsin-Madison. 63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-90-2048.jpg)

![Created by Christy Owen of Liberty University’s Online

Writing Center

[email protected]; last date modified: February 7, 2022

Sample APA Paper: Professional Format for Graduate/Doctoral

Students

Claudia S. Sample

School of Behavioral Sciences, Liberty University

Author Note

Claudia S. Sample (usually only included if author has an

ORCID number)

I have no known conflict of interest to disclose.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-93-2048.jpg)

![Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Claudia S. Sample.

Email: [email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE/DOCTORAL

STUDENTS 2

Table of Contents

(Only Included for Easy Navigation; Hyperlinked for Quick

Access)

Sample APA Paper: Professional Format for Graduate/Doctoral

Students .................................... 6

Basic Rules of Scholarly Writing

...............................................................................................

.... 7

Brief Summary of Changes in APA-7

.............................................................................................

8

Running Head, Author Note, and Abstract

..................................................................................... 9

Basic Formatting Elements](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-94-2048.jpg)

![Students

The title of your paper goes on the top line of the first page of

the body (American

Psychological Association [APA], 2019, section 2.11). It should

be centered, bolded, and in title

case (all major words—usually those with four+ letters—should

begin with a capital letter)—see

p. 51 of your Publication Manual of the American Psychological

Association: Seventh Edition

(APA, 2019; hereinafter APA-7). It must match the title that is

on your title page (see last line on

p. 32). As shown in the previous sentence, use brackets to

denote an abbreviation within

parentheses (bottom of p. 159). Write out the full name of an

entity or term the first time

mentioned before using its acronym (see citation in first

sentence in this paragraph), and then use

the acronym throughout the body of the paper (section 6.25).

There are many changes in APA-7. One to mention here is that

APA-7 allows writers to

include subheadings within the introductory section (APA,

2019, p. 47). Since APA-7 now

regards the title, abstract, and term “References” to all be

Level-1 headings, a writer who opts to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-102-2048.jpg)

![SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE/DOCTORAL

STUDENTS 18

APA-7 now invites writers to prioritize or highlight one or more

sources as most prominent or

relevant for that content by placing “those citations first within

parentheses in alphabetical order

and then insert[ing] a semicolon and a phrase, such as ‘see

also,’ before the first of the remaining

citations” (APA., 2019, p. 263)—i.e., (Cable, 2013; see also

Avramova, 2019; De Vries et al.,

2013; Fried & Polyakova, 2018). Periods are placed after the

closing parenthesis, except with

indented (blocked) quotes.

Two Works by the Same Author in the Same Year

Authors with more than one work published in the same year are

distinguished by lower-

case letters after the years, beginning with a (APA, 2019,

section 8.19). For example, Double

(2008a) and Double (2008b) would refer to resources by the

same author published in 2008.

When a resource has no date, use the term n.d. followed by a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-126-2048.jpg)

![12 Ancient Greek or Roman work.

13 Webpage on a news website.

14 Chapter in an edited book with DOI.

15 Resources by two authors with the same last name but

different first names in the same year of

publication. Arrange alphabetically by the first initials.

http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/03/health/respect-toward-elderly-

leads-to-long-life-intl/index.html

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/03/health/respect-toward-elderly-

leads-to-long-life-intl/index.html

https://doi.org/10.1037/0000119-012

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615800802638279

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 32

Cable, D. (2013). The racial dot map [Map]. University of

Virginia, Weldon Cooper Center for

Public Service. https://demographics.coopercenter.org/Racial -

Dot-Map 16

Canan, E., & Vasilev, J. (2019, May 22). [Lecture notes on

resource allocation]. Department of

Management Control and Information Systems, University of

Chile. https:// uchilefau.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-154-2048.jpg)

![16 Map.

17 PowerPoint slides or lecture notes.

18 Online journal article with a URL and no DOI; also depicts

one of two resources by the same

author with no known publication date.

19 Webpage on a website with a group author.

20 Journal article with a DOI, combination of individual and

group authors.

21 Two resources by same author in the same year. Arrange

alphabetically by the title and then

add lowercase letters (a and b, respectively here) to the year.

https://demographics.coopercenter.org/Racial-Dot-Map

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.07.007

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 33

Fistek, A., Jester, E., & Sonnenberg, K. (2017, July 12-15).

Everybody’s got a little music in

them: Using music therapy to connect, engage, and motivate

[Conference session].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-156-2048.jpg)

![Autism Society National Conference, Milwaukee, WI, United

States.

https://asa.confex.com/asa/2017/webprogramarchives/Session95

17.html 22

Forman, M. (Director). (1975). One flew over the cuckoo’s nest

[Film]. United Artists. 23

Fried, D., & Polyakova, A. (2018). Democratic defense against

disinformation. Atlantic Council.

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-

reports/report/democratic-defense-

against-disinformation/ 24

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., & Heatherton, L. (2002). E-

SOFTA: System for observing

family therapy alliances [Software and training videos]

[Unpublished instrument].

http://www.softa-soatif.com/ 25

GDJ. (2018). Neural network deep learning prismatic [Clip art].

Openclipart.

https://openclipart.org/detail/309343/neural-network-deep-

learning-prismatic 26

Goldberg, J. F. (2018). Evaluating adverse drug effects

[Webinar]. American Psychiatric

Association.

https://education.psychiatry.org/Users/ProductDetails.aspx?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-157-2048.jpg)

![Methodological innovations and new lessons

from the Milgram experiment (Publication No. 10289373)

[Doctoral dissertation,

University of Wisconsin-Madison]. ProQuest Dissertations and

Theses Global. 33

Hutcheson, V. H. (2012). Dealing with dual differences: Social

coping strategies of gifted and

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adolescents

[Master’s thesis, The College

28 Newspaper article without DOI, from most academic

research databases or print version

29 Entry in a dictionary, thesaurus, or encyclopedia, with

individual author.

30 Online newspaper article.

31 Edited book without a DOI, from most academic research

databases or print version.

32 Book chapter, print version.

33 Doctoral dissertation, from an institutional database.

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/behaviorism

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-160-2048.jpg)

![https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-

science/wp/2017/12/04/how-will-humanity-react-to-alien-life-

psychologists-have-some-predictions/

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 35

of William & Mary]. William & Mary Digital Archive.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd/1539272210/ 34

Kalnay, E., Kanimitsu, M., Kistler, R., Collins, W., Deaven, D.,

Gandin, L., Iredell, M., Saha, S.,

White, G., Whollen, J., Zhu, Y., Chelliah, M., Ebisuzaki, W.,

Higgins, W., Janowiak, J.,

Mo, K. C., Ropelewski, C., Wang, J., Leetmaa, A., … Joseph,

D. (1996). The

NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bulletin of the

American Meteorological

Society, 77(3), 437-471. http://doi.org/ fg6rf9 35

King James Bible. (2017). King James Bible Online.

https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/

(Original work published 1769) 36

Lewin, K. (1999). Group decision and social change. In M. Gold](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-161-2048.jpg)

![https://www.liberty.edu/online/casas/%20writing-center/

https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A

%2F%2Flearn.liberty.edu%2F&data=02%7C01%7Ccmowen2%4

0liberty.edu%7Cb709d48eab614c47330308d7f67e8f9c%7Cbaf8

218eb3024465a9934a39c97251b2%7C0%7C0%7C63724889575

8832975&sdata=2kfyvpGtDiu0nVnT%2Fy0%2BUXZcfAi%2FB

AadIm9QwtjT0g8%3D&reserved=0

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 36

McCauley, S. M., & Christiansen, M. H. (2019). Language

learning as language use: A cross-

linguistic model of child language development. Psychological

Review, 126(1), 1-51.

https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000126 40

McCurry, S. (1985). Afghan girl [Photograph]. National

Geographic.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/national-

geographic-magazine-50-years-

of-covers/#/ngm-1985-jun-714.jpg 41

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Heuristic. In Merriam-Webster.com

dictionary. Retrieved 01/02/2020,

from http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/heuristic 42

National Cancer Institute. (2018). Facing forward: Life after

cancer treatment (NIH Publication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-163-2048.jpg)

![714.jpg

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/national-

geographic-magazine-50-years-of-covers/#/ngm-1985-jun-

714.jpg

http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/heuristic

https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/life-

after-treatment.pdf

https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/pages/what-employers-

should-do-to-protect-rns-from-zika

https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/pages/what-employers-

should-do-to-protect-rns-from-zika

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 37

Owen, C. (2012, Spring). Behavioral issues resulting from

attachment have spiritual

implications [Unpublished manuscript]. COUN502, Liberty

University. 46

Perigogn, A. U., & Brazel, P. L. (2012). Captain of the ship. In

J. L. Auger (Ed.) Wake up in the

dark (pp. 108-121). Shawshank Publications. 47

Peters, C. (2012). COUN 506: Integration of spirituality and

counseling. Week one, lecture two:

Defining integration: Key concepts. Liberty University.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/defining-integration-key-

concepts/id427907777?i=1000092371727 48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-165-2048.jpg)

![Pew Research Center. (2018). American trend panel Wave 26

[Data set].

https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/dataset/american-trends-panel-

wave-26 49

Prayer. (2015). http:// www exact-webpage 50

Project Implicit. (n.d.). Gender–Science IAT.

https://implicit.harvard.edu/implici/taketest.html 51

Schatz, B. R. (2000, November 17). Learning by text or

context? [Review of the book The social

life of information, by J. S. Brown & P. Duguid]. Science, 290,

1304.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5495.1304 52

Schmid, H.-J. (Ed.). (2017). Entrenchment and the psychology

of language learning: How we

reorganize ad adapt linguistic knowledge. American

Psychological Association; De

46 Citing a student’s paper submitted in a prior class, in order

to avoid self-plagiarism.

47 Chapter from an edited book.

48 Liberty University class lecture using course details.

49 Data set.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-166-2048.jpg)

![146). https://doi.org/10.1037/10762-000 56

Tellegen, A., & Ben-Porah, Y. S. (2011). Minnesota

Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2

Restructured Form (MPI-2-RF): Technical manual. Pearson. 57

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). U.S. and world population clock.

U.S. Department of Commerce.

Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/popclock

58

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2017). Agency

financial report: Fiscal year 2017.

https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2017-agency-financial-report.pdf

59

University of Oxford. (2018, December 6). How do geckos walk

on water? [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qm1xGfOZJc8 60

53 Edited book with a DOI, with multiple publishers.

54 Two resources by the same author, in different years.

Arrange by the earlier year first.

55 Shakespeare.

56 Electronic version of book chapter in a volume in a series

57 Manual for a test, scale, or inventory.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-168-2048.jpg)

![58 Webpage on a website with a retrieval date.

59 Annual report.

60 YouTube or other streaming video.

https://doi.org/10.1037/15969-000

https://doi.org/10.1037/10762-000

https://www.census.gov/popclock

https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2017-agency-financial-report.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qm1xGfOZJc8

SAMPLE APA-7 PAPER FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS 39

Vedentam, S. (Host). (2015-present). Hidden brain [Audio

podcast]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/

series/423302056/hidden-brain 61

Weinstock, R., Leong, G. B., & Silva, J. A. (2003). Defining

forensic psychiatry: Roles and

responsibilities. In R. Rosner (Ed.), Principles and practice of

forensic psychiatry (2nd

ed., pp. 7-13). CRC Press. 62

Yoo, J., Miyamoto, Y., Rigotti, A., & Ryff, C. (2016). Linking

positive affect to blood lipids: A

cultural perspective [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of

Psychology, University of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-169-2048.jpg)

![behavior were significant. The technician’s seemingly flippant

attitude toward

the apparent dangers appeared unusual. I concluded that little

could be done

to reason with her. When behavior is assumed to be entirely

random, one

might be tempted to conclude, as I did, that nothing can be done

to change it

(Johnston, 2014). This conclusion may be further pronounced if

the employee

works alone or in isolation and is unable to be observed or

managed. However,

when examining the variables systematically, it becomes clear

that behavior is

not random and can be understood and managed (Johnston,

2014).

Furthermore, behavior does not have to be managed by a

supervisor. An

alternative approach to behavior change is available that

requires less support

from management and may prove to be a viable option for

workers like the

one described in this example.

CONTACT Rachael Ferguson [email protected] School of

Behavior Analysis, Florida Institute of Technology, 150

W University Blvd., Melbourne, FL, 32901, USA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the

publisher’s website.

JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR

MANAGEMENT

2022, VOL. 42, NO. 3, 210–229

https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2021.1996502](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-175-2048.jpg)

![https://pubs.acs.org/toc/jceda8/97/10?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org/toc/jceda8/97/10?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org/toc/jceda8/97/10?ref=pdf

pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org?ref=pdf

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc?ref=pdf

https://pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc?ref=pdf

later gave them the overall reaction, aiming to investigate

whether external representations might evoke problem-solving

strategies.7 They stated that traditional tasks such as giving

students reagents, solvents, and products may not be the most

effective assessment to engage students in problem-solving.

They concluded that asking participants to consider inter -

mediates and multiple reaction centers might have helped

them to think more deeply about chemical transformations.7

Bhattacharyya and Bodner8 investigated problem-solving in

organic synthesis with electron-pushing tasks. They observed

that “rather than solving chemical problems, [students] were

essentially playing with puzzles” (p. 1406). We surmise that

this was because students focused on remembering reaction

products.

To summarize, a key goal of chemistry education research

that focuses on problem-solving is as follows: To help students

become aware that their analysis about reaction mechanisms

requires them to consider and apply underlying chemical

concepts and principles in order to make a judgment about the

plausibility of reactions.

■ THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE

On a continuum from meaningful learning to rote learning, it](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-232-2048.jpg)

![pathways, we asked participants to reflect on supportive

conditions. Most students gave similar answers. Cameron’s

answer is an example of the most prevalent opinion.

Cameron: “The problem is for these kinds of tasks that you

need someone to discuss it with. [···] A fellow student would

be sufficient for this. It would be enough if he said ‘How do

you come to this conclusion?’ You don’t need someone who

knows the correct answer, only someone asking ‘Why this

answer?’ I prefer this [approach to problem-solving].”

In general, students said that a partner would be crucial for a

valuable discussion, since they were less likely to think about a

problem in depth on their own than in discussion with a fellow

student. Working with a partner, or cooperative learning, is an

essential part of active learning.35,36 When solving tasks on

their own, with a partner or in groups, discussions are more

likely to motivate students to engage in counter-arguments and

to think beyond the surface to reason out the “chemical

processes that run in the background,” as Mitchell remarked.37

Participants were also asked to compare the tasks presented

that they had experienced during their study program. For

instance, Claire was asked this question after tasks A and B. In

her answer, she compared the tasks to the traditional exercises

she had experienced as follows.

Claire: “I haven’t done something like this in the last two

years because you’ve just got something in front of you

telling you that this is the mechanism of the reaction and

that’s it. [···] But I should have created a concept that I

could refer back to.”

Claire emphasized that the traditional environment provided](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-246-2048.jpg)

![her with the correct reaction mechanisms and did not prompt

her to reason out the underlying chemical concepts. About

three-quarters of the participants gave similar answers stating

that they did not think about the concepts they should have

learned in the traditional lecture setting. Claire emphasized her

experience with the traditional setting again after task B as

follows.

Claire: “During [my studies in] the last few years, things

have just been written in the board and you copied it down.

You could’ve just copied the textbook instead.”

Claire mentioned that in the traditional setting she only

copied sample solutions that were written on the board. In

contrast, studies have revealed that students work more

intensively and learn more in cooperative learning environ-

ments than in traditional setting because active learning

approaches provide more opportunities for discussion.37,38

This could be because traditional settings convey a vast

amount of information in a brief time span so that students use

Journal of Chemical Education pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc Activity

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248

J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 3731−3738

3735

pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc?ref=pdf

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248?ref=pdf

the rote learning approach to cope with the deluge of

information. In this study, the presented tasks created learning

settings in which students had the opportunity for discussion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-247-2048.jpg)

![when implementing the tasks in the actual classrooms. This is

because the interviews may have influenced students in the

study to use their reasoning and analytical skills more

intensively than they would have used it normally.

The tasks were primarily designed as a diagnostic tool to

analyze organic chemistry students’ problem-solving approach

and their difficulties when reflecting on alternative reaction

products. However, to what extent the task-design will

influence students’ reasoning behavior cannot be determined

based on our current study.

■ ASSOCIATED CONTENT

*sı Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available at https://pubs.ac-

s.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248.

Task A/B, corresponding product cards, and sample

solutions (PDF, DOCX)

■ AUTHOR INFORMATION

Corresponding Author

Nicole Graulich − Institute of Chemistry Education, Justus-

Liebig-University Giessen, Giessen 35392, Germany;

orcid.org/0000-0002-0444-8609;

Email: [email protected]

Journal of Chemical Education pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc Activity

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248

J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 3731−3738

3736](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-251-2048.jpg)

![https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jchemed. 0c00248?goto=sup

porting-info

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248?goto=sup

porting-info

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/suppl/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248/sup

pl_file/ed0c00248_si_001.pdf

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/suppl/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248/sup

pl_file/ed0c00248_si_002.docx

https://pubs.acs.org/action/doSearch?field1=Contrib&text1="Ni

cole+Graulich"&field2=AllField&text2=&publication=&access

Type=allContent&Earliest=&ref=pdf

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0444-8609

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0444-8609

mailto:[email protected]

pubs.acs.org/jchemeduc?ref=pdf

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248?ref=pdf

Author

Leonie Lieber − Institute of Chemistry Education, Justus-

Liebig-

University Giessen, Giessen 35392, Germany; orcid.org/

0000-0001-9955-6655

Complete contact information is available at:

https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00248

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication is part of the first author’s doctoral (Dr. rer.

nat.) thesis at the Faculty of Biology and Chemistry, Justus-

Liebig-University Giessen, Germany. We thank the students](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-252-2048.jpg)

![Corresponding author:

Phillipa K. Chong, Department of Sociology, McMaster

University, Hamilton, Canada.

Email: [email protected]

Work and Occupations

! The Author(s) 2021

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/07308884211017623

journals.sagepub.com/home/wox

2021, Vol. 48(4) 432–469

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2509-8003

mailto:[email protected]

http://us.sagepub.com/en-us/journals-permissions

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07308884211017623

journals.sagepub.com/home/wox

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1177%2F07308884

211017623&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2021-05-26

general value of a typology of dilemma work for understanding

workers’

experience both within artistic labor markets, and beyond.

Keywords](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-263-2048.jpg)

![dilemma work, non-standard work, portfolio careers,

occupational general-

ism, role theory, artistic careers, identity, skill, values, book

reviewers

I’m primarily a novelist and a writer, and then

I also teach creative writing [and] I occasionally review books.

— occasional reviewer for the LA Times Book review

I freelance as a book reviewer, and sometimes a general feature

writer,

I also teach as an adjunct professor.

— occasional reviewer for The New York Times and NPR

In their introduction to aWork and Occupations special issue on

artistic

careers, Lingo and Tepper (2013) remark on artistic workers’

growing

tendency to invest in “broad competencies , rather than

discipline-

specific skills” (341). This trend has been termed occupational

general-

ism (Cornfield, 2015; Frenette & Dowd, 2018; Lingo & Tepper,

2013;

Pinheiro & Dowd, 2009). 1 The opening quotes, for instance,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-264-2048.jpg)

![can also produce their own recordings and publish their own

work (i.e.

what Nash(1970 [1955]) called “role versatility”) (Thomson,

2013).

Similarly, artists who take on teaching jobs achieve creative

indepen-

dence in their artistic practice (Gerber, 2017, p. 45). Similar

findings are

reported for workers in non-artistic fields, such as Caza et al.’s

(2018)

study of plural careerists, who report that occupying very

different

work roles can enhance creativity. As one of the authors’

respondents

explained, occupying multiple, relatively dissimilar jobs

sharpened up

their skill in terms of generating creative ideas for clients:

“‘The

work with children’s business education sometimes sparks an

idea for

437Chong

a client; or a freelance piece might give me an idea for a

dentistry

client’” (p. 729).

Scholars have also precisely captured the heterogeneity among

those

who take multiple jobs. For instance, people vary in terms of

the spe-

cific conditions that propel them to undertake multiple jobs, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-276-2048.jpg)

![know, I wasn’t happy about it. I try not to think about the

author,

[because] I know it really is pretty disheartening to get a

negative

review, especially in The New York Times, which is such a

prominent

publication.” He speaks from personal experience as an author

who has

received his fair share of negative reviews. Many other

respondents also

express a sense of regret over the hurt caused by a negative

review—

particularly those who have received bad reviews themselves.

A common dilemma facing author-critics, then, is whether to

“pull

their punches” and give a book a kinder review than it deserves,

in

order to spare the author further pain. This critic pivots towards

his

professional experience as a journalist to resolve this dilemma

and steel

himself for the unpalatable—indeed, “painful”—task of

forthright

criticism.

First, he justifies being frank with his criticism through

reference to

fairness and integrity. “If I’m going to be fair to the writers

who do

great books, I’ve got to be negative toward the writers who

don’t do

great books. So I feel there is some amount of integrity

involved. I just

feel crummy.” Fairness and integrity are core to the self-image

of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-300-2048.jpg)

![journalistic profession (Schudson, 2001; Ward, 2015). While the

critic

may still feel “crummy” writing a negative review, his decision

to be

plain in his criticism is buttressed by these appeals to core

journalistic

values. Since dilemmas often have no satisfactory resolution,

this is his

least-worst option.

Second, this critic decenters the evaluative function of book

reviews,

and instead positions them as pieces of journalistic writing.

“The most

446 Work and Occupations 48(4)

interesting thing about a book isn’t that [I] think that it’s good

or bad,”

he insists. Instead, “As a journalist, you’ve really got to find the

news

value.” Arguing that evaluation is not the core of his task as a

reviewer,

he appeals to the journalistic value of keeping oneself out of the

story

(Schudson, 2001).

There is precedent for regarding book reviews as cultural

journalism

(Chong, 2019). However, it is noteworthy that when this critic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-301-2048.jpg)

![individual who makes a living from combining multiple work

roles, one

of which is book reviewing. Unlike the previous reviewer,

though, this

critic uses his work role as a writer as an anchor to resolve the

dilemmas

of writing a negative review.

At the time of our interview, the critic had published two books

and

was working on his third. His approach to reviewing is very

much

anchored in his role as author, in terms of how he makes sense

of

both phases of his work, evaluation and writing the review. For

instance, when I ask him about writing negative reviews, his

first

response is to reflect on his own experience as an author. “I’ve

been

on the receiving end of some extremely convoluted [reviews],

you know,

reviews that are positive and negative at once, and you’re just

like,

‘Huh?’” Having been unsure how to interpret feedback that he

found](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-305-2048.jpg)

![incoherent, he is committed to being very clear in his own

reviews.

He then continues:

So I’m reading [a book] and I’m thinking, “Fuck,” you know,

“It’s really

good.” But is it really? Or am I just wanting it to be good

because then I

don’t have to have this moral conundrum of, “Am I responsible

for

harming some writer’s career?” You know, do I want to dish

something

out that I, myself, would be totally loath to be on the receiving

end of?

Here, we see that the reviewer draws on his own experience of

receiving

reviews to contextualize his own approach. Additionally, he

anticipates

the future dilemma of potentially having to write a negative

review, and

he wishes to avoid it. So although he strives for clarity in his

own

reviews, he still brings his own experience of being reviewed to

his](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-306-2048.jpg)

![evaluation of others’ work.

Recalling an instance when he could not avoid writing a

negative

review, the same reviewer again relies on his anchor identity as

an

author to make sense of conflict. “I thought, ‘Gee, [author] is

[religion]

like me, and about my age,’” he recalls. “Am I being—you

know, like,

am I competing with him? Do I feel threatened by him?” In the

previous

example, the critic referred to his writing identity to work out

whether

he was trying to convince himself that he liked a book in order

to avoid

writing a negative review. Here, he draws on the same identity

to ask

448 Work and Occupations 48(4)

himself whether he disliked a book in order to ensure it

necessitated a

negative review, because of his perceived relationship with the

author.

However, while this reviewer’s identity as a writer is the source

of his](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-307-2048.jpg)

![is just one type of writing from which this respondent makes his

living.

Like all reviewers, he has to write positive, negative, and mixed

reviews. But unlike previous respondents, he exhibits no guilt

or anxiety

over writing a negative review. “Does one get a bad feeling

after giving

a bad review?” he ponders. “No, certainly no more than [after]

giving a

good review to a bad book. I think, in the end, book reviewing

is about

honesty—honesty with yourself, and honesty with others.”

At first sight, this critic’s response would seem to be an outlier

in terms

of his very clear-headed view. He prioritizes honesty above all,

and there-

fore it seems he has no real dilemma work to do—for him,

honesty is the

best policy, regardless of the situation. Seeing his approach, we

might

conclude that the previous two reviewers were merely fretful, or

over-

thinking it. However, in fact, this reviewer is acutely aware of

the of the

professional and ethical dilemmas that critics face when writing

a review.

“I come from a [foreign] country, where book reviewing was

always

tarnished by friendship and camaraderie, [and] you would never

really

know whether the book was good,” he explains. “You would

know

exactly who was having drinks with whom.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-311-2048.jpg)

![that many other critics publicly praised:

When big books are published . . .by a big publisher, I might be

critical

because I think that the big publisher simply went for the easy

novel, the

450 Work and Occupations 48(4)

one that is going to sell more copies rather than a more

complicated and

demanding author or novel. I will criticize that in public.

For instance, some years ago, for The Washington Post, I did a

critical

review of a [foreign] author who had written a novel [and] I was

very

critical. Other people praised the book. I thought the book was

lousy.

There are other [foreign] writers that could be published by a

big pub-

lishing house, but this book was sexy. It had violence, lunacy

and so on,

and I guess the editor thought this was going to attract readers.

I don’t

know whether it did or not, but I was critical. Other people were](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-313-2048.jpg)

![roles. In

contrast to the anchoring strategy, however, the reviewer role is

not

superseded by another; rather, the two roles are viewed as

compatible

or mutually complementary, forming part of a larger mission.

This distinction is echoed in the example of another reviewer

who

identifies primarily as a writer. “I am primarily a fiction and

non-fiction

writer; a book writer,” she says. However, rather than letting

the writer

role dictate how she resolves reviewing dilemmas, she

incorporates her

writer identity into her reviewing practice. For instance, she

suggests

that her artistic work as an author is what qualifies her to be a

reviewer:

“I believe I’ve been given the books that I have been given

because the

editors [. . .] think that I’ll have some interesting perspective,

from an

artistic point of view, on the material.” When I ask this

reviewer to

451Chong

recount her experiences of writing negative reviews, she first

says that

she tends to give “mixed” reviews. When she does write a more

negative](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-315-2048.jpg)

![review, she reveals, “[T]o be totally honest, it’s the hardest

thing I do,

and I don’t really enjoy it that much.”

Part of the reason is the social and professional risk involved in

writing a negative review, as discussed above. “It’s putting your

profes-

sional, sort of . . . your reputation and also your relationships

with other

writers, on the line, by writing negatively about a book.” To

mitigate

this risk of harm to herself through writing a negative review,

the

reviewer treads carefully, avoiding “brash negative statements

about

the book itself.” In dissecting a book, she views herself as

diligently

fair to the author; in particular, she emphasizes specific

passages in her

reviews, always being mindful that “every writer is good at

some things,

and every writer is not so good at other things.” To her mind,

she offers

a scrupulously balanced aesthetic evaluation of the book, which

follows](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-316-2048.jpg)

![from her perception that it is her artistic skills as an author that

qualify

her to be a reviewer in the first place.

For this reviewer, this technical dissection offers lessons about

the

craft of writing, which she then brings back to her own writing

practice.

And this is why she works as a reviewer, even though she finds

writing

negative reviews difficult and even unenjoyable:

[Reviewing] is very difficult. I do find it extremely time-

consuming. There

isn’t a whole lot of reward for it, and especially if it’s a

negative review.

That said, I think it helps me to hone my own criteria, my own

way of

looking at fiction, by doing this, because it’s extremely

important that

you believe in the assertions you’re making and that you’re

willing to

stand behind them.

In this example, we see that this reviewer chooses to continue to

put her

professional reputation and relationship with other writers on](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-317-2048.jpg)

![to

approach their dilemma work is by compartmentalizi ng their

various

work roles. In this approach, individuals bracket the values and

identity

commitments of their other roles, and work within the

parameters of one

identity exclusively—in this case, that of a reviewer. They

temporarily put

on “blinders,” so to speak. The critics who employ this strategy

recognize

the dilemmas presented by reviewing, but choose to close off

their aware-

ness of the tensions between their multiple roles and proceed as

though

reviewing was their sole profession and responsibili ty.

One illustrative example is a reviewer who, like many

respondents,

describes her career as atypical: “There are a lot of things that

go into

what I do [for a living].” She also engages in freelance

journalism and

writes books (at the time we spoke, she was working on her

second). But

unlike the previous examples, when describing her approach to

review-

ing, she refers to her role as a critic to the exclusion of any

other role. For

instance, when I ask her how she feels about writing negative

reviews, she

singularly situates her approach vis-à-vis well-known

reviewers:

I’ve talked about this before [with] Ron Charles, a lot of times .

. . I know](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-319-2048.jpg)

![Another example comes from a critic who has authored four

books,

but also privileges his reviewer roles to the exclusion of any

others,

when engaged in a review assignment. Similar to the previous

reviewer,

he describes a sense of ease when tasked with writing a negative

review.

“Negative reviews are sometimes the easiest reviews to write,”

he

opines, because he has a lot to say if he passionately feels that

the

book is bad. Like the previous reviewer, he also relies on a

technocratic,

“due process” view of his reviewing to explain his neutral

feeling

towards negative reviews. “I neither like nor dislike writing [a

negative

review],” he states. “I write the review that presents itself, you

know? I

read a book, I have the response to the book, and then I have to

write

honestly about my response to it.” However, ironically, such a

mecha-

nistic approach to book reviewing takes significant personal

effort. The

critic explains that he aims to block out the social politics and

tensions

that accompany reviewing. For instance, he says that he tries

not to

“think of [the] audience,” because reviewing has “got to be

private

between me and the book, because I need the space to be able to

hon-

estly explore what I think about the book.” This is an active](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-324-2048.jpg)

![Uncharacteristically of the many reviewers I interviewed, this

critic

appears nonchalant, or at least not greatly perturbed, by writing

a neg-

ative review. This partly results from him downplaying the

significance

of his judgment—just like the previous, high-status reviewer.

The reviewer faces the dilemma of knowing that writing a

negative

review can inflict pain and disappointment on the author—a

position he

has been in himself. But he compartmentalizes his experiences

as an

author and focuses instead on his function as a critic, which is

to eval-

uate the book (which he sees as merely “a product”).

I don’t feel any constraint. I want to be fair, you know, because

[writing]

takes a lot of time, and nobody invests in writing a novel

without some

kind of aspiration to achieve something. You don’t want to

insult that

aspiration, which should be encouraged, but in the end, you’re

evaluating

the success of a product.

A review can be many things to many people. We have seen a

journalist

position his reviews as “entertaining” articles, and another

reviewer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-327-2048.jpg)

![4. In 2015, I reached out to a few interviewees to confirm the

completeness of

my understanding of the data.

5. Book reviewing is by no means a taken-for-granted activity

or extension of a

career as a novelist; however, a sizable proportion of fiction

critics are them-

selves published novelists.

6. It is possible this respondent was merely name-dropping. But

her primary

focus on the critic role to the exclusion of all her other

professional experi-

ences extends beyond this one comment about her friendship

networks.

7. This critic isn’t alone in receiving feedback on her reviews

from authors. But

she is peculiar in the number of positive examples of flattering

feedback she

can apparently recall. For instance, she describes a particular

instance of

writing a negative review and getting a positive response:

[T]here was a character that just wasn’t well-formed enough. I

wrote the

reviewand talked agreat deal about [. . .] the problems that I

hadwith the

character. I got a message from [the author] a week or so later

saying,

“You know, this is incredible. Thank you somuch. You’ve

givenme the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-349-2048.jpg)

![Psychology Quarterly, 77(4), 319–343.

Hall, D. T. (1996). The new protean career: Psychological

success and the path

with aheart. In D. T. Hall (Ed.), The career is dead-long live the

career: A

relational approach to careers (pp. 15–45). Jossey Bass.

Henaut, L., & Lena, J. (2019, April 19). Polyoccupationalism: A

challenge for

the study of work and occupation [Workshop]. Teachers

College, Columbia

University, New York City, NY, United States.

Hipple, S. F. (2010). Multiple jobholding during the 2000s.

Monthly Labour

Review, 133(7), 21–32.

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: Work,

family, and gender

inequality. Harvard University Press.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers:

Employment rela-

tions in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22.

Lale, E. (2015). Multiple jobholding over the past two decades.

Monthly Labor

Review. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/multipl e-

jobholding-

over-the-past-two-decades.htm

467Chong](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-355-2048.jpg)

![and Social

Behavior, 36, 259–273

Morrison, R. F., & Hall, D. T. (2002). Career adaptability.

Careers In and Out

of Organizations, 7, 205–232.

Nash, D. (1970 [1955]). The American composer’s career. InM.

Albrecht &M. G.

JBarnett (Eds.), The sociology of art and literature (pp. 256–

265). Duckworth.

Nomaguchi, K. M. (2009). Change in work-family conflict

among employed

parents between 1977 and 1997. Journal of Marriage and

Family, 71, 15–32.

O’Mahoney, J. (2011). Advisory anxieties: Ethical

individualisation in the UK

consulting industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(1), 101–

113.

Panos, G., Konstantinos, P., & Alexandros, Z. (2014). Multiple

job holding,

skill diversification, and mobility. Industrial Relations: A

Journal of Economy

and Society, 53(2), 223–272.

Patton, M.Q. (2007). Sampling, Qualitative (Purposive). In G.

Ritzer (Ed.). The

Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1002/

9781405165518.wbeoss012

Pinheiro, D. L., & Dowd, T. J. (2009). All that jazz: The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-357-2048.jpg)

![supervisor. An

alternative approach to behavior change is available that

requires less support

from management and may prove to be a viable option for

workers like the

one described in this example.

CONTACT Rachael Ferguson [email protected] School of

Behavior Analysis, Florida Institute of Technology, 150

W University Blvd., Melbourne, FL, 32901, USA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the

publisher’s website.

JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR

MANAGEMENT

2022, VOL. 42, NO. 3, 210–229

https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2021.1996502

© 2021 Taylor & Francis

https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2021.1996502

http://www.tandfonline.com

https://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1080/01608061.2

021.1996502&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2022-07-18

Defining self-management

Self-management has been conceptualized as a process of self-

improvement

that involves changing one’s behavior to a desired level that is

consistent with a

goal (Hickman & Geller, 2005). In self-management, the

individual assumes

“responsibility” for their behavior, therefore lessening the need](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmal500researchpaperassignmentinstructionsoverviewplease-220930134217-684de1a9/75/BMAL-500Research-Paper-Assignment-InstructionsOverviewPlease-377-2048.jpg)