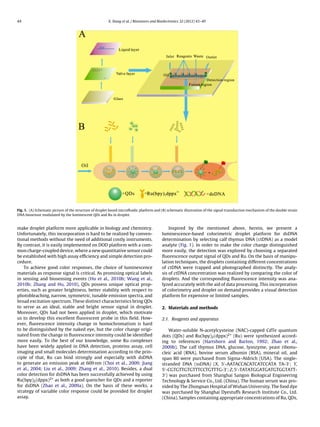

This document describes the development of a new luminescence-based colorimetric droplet platform for the determination of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The platform uses a fluorescent ensemble probe comprising quantum dots and Ru(bpy)2(dppx)2+ that serves as both a quencher for the quantum dots and a reporter for dsDNA. Droplet size and fusion is precisely controlled using a microfluidic chip with microvalves. The concentration of dsDNA can be determined by comparing the color of droplets, with increasing dsDNA concentration resulting in a gradually enhanced color response. The platform provides a simple, efficient, and visual method for dsDNA analysis using small volumes of sample in droplets.