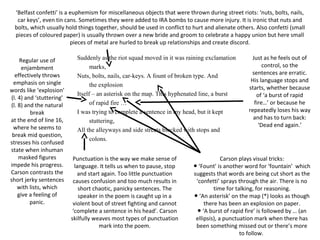

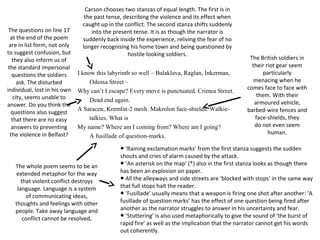

The poem describes a man caught in violent sectarian riots in Belfast during The Troubles. As explosions and gunfire erupt, he tries to flee but is blocked around every corner by barricades and security forces. Disoriented and confused, he no longer recognizes the streets of his hometown. When confronted by armed British soldiers, he is unable to answer their questions about his identity and intentions amid the chaos. The poem uses punctuation metaphorically to convey the man's fragmented state of mind and the breakdown of normal communication.