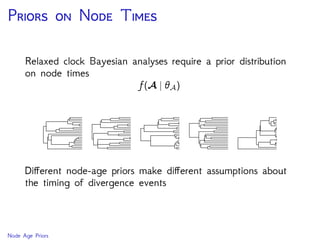

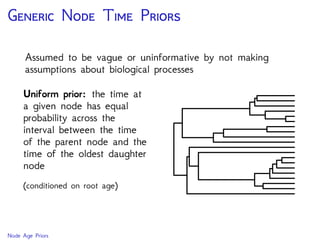

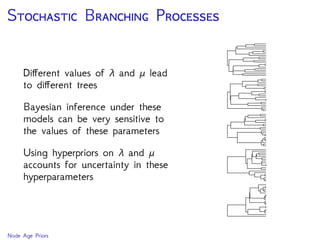

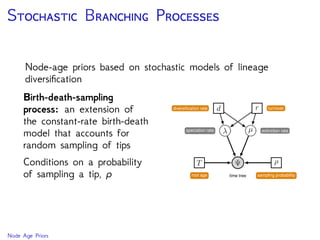

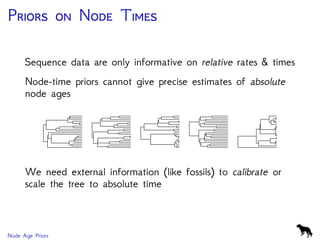

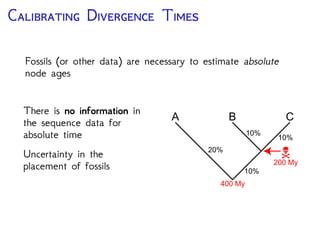

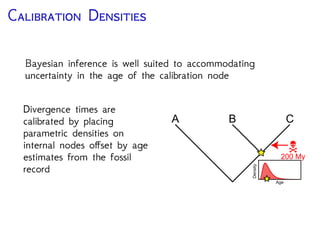

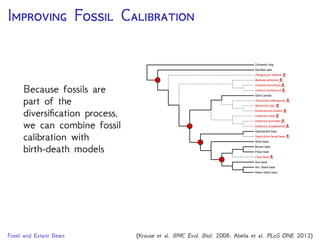

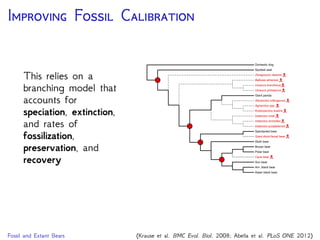

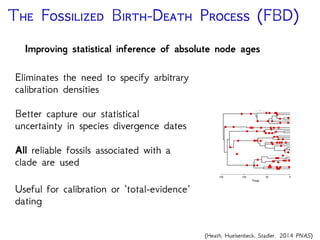

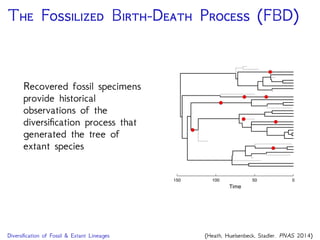

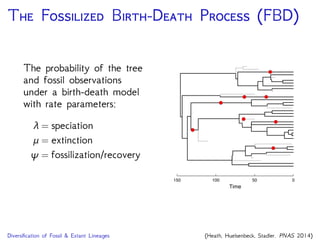

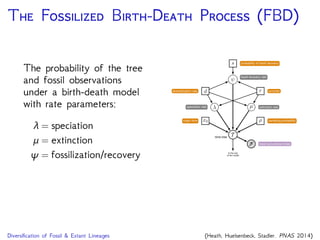

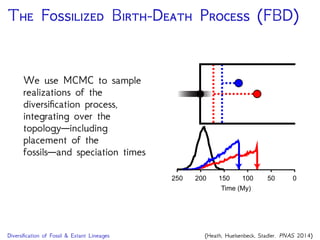

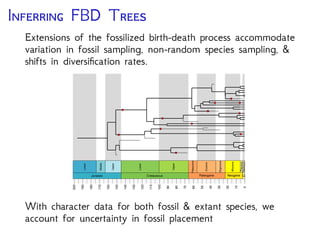

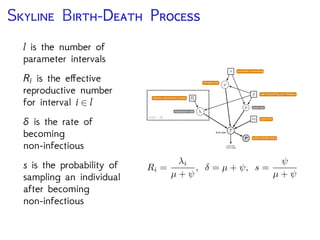

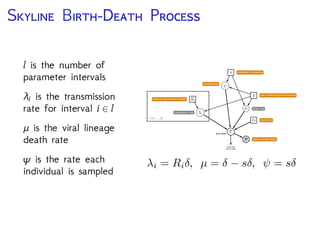

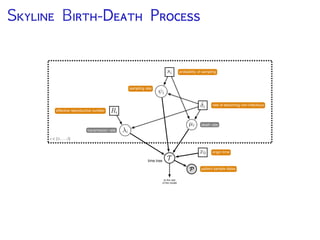

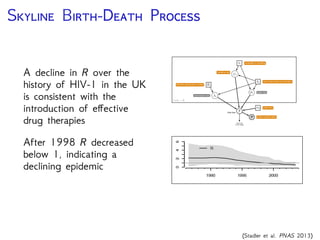

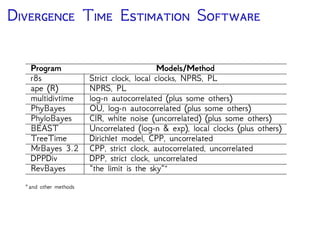

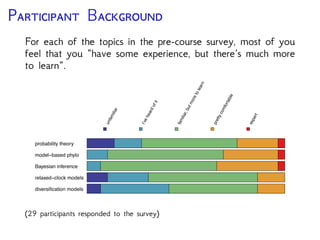

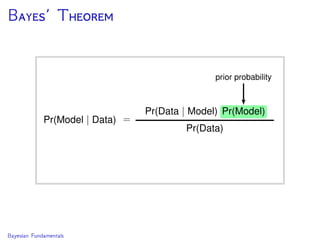

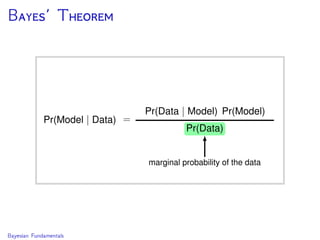

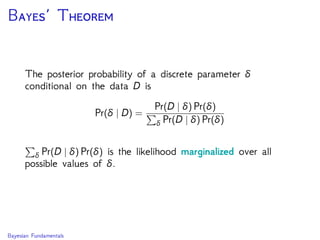

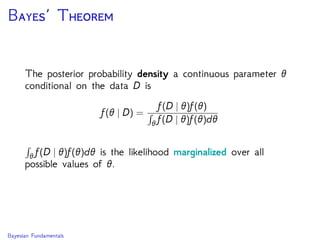

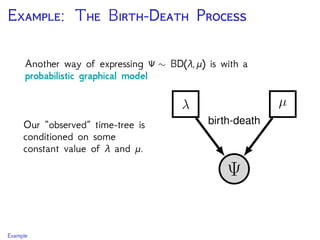

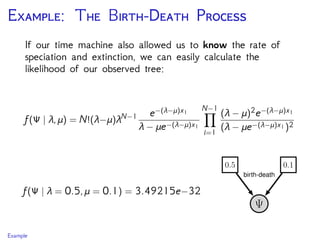

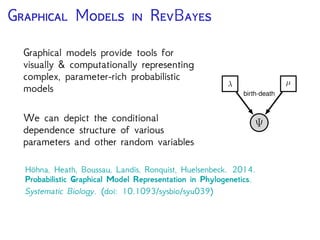

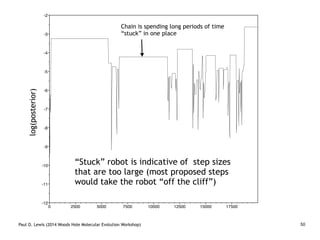

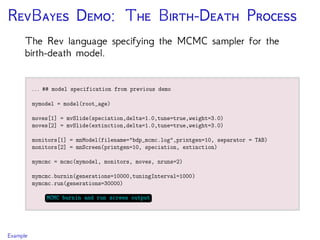

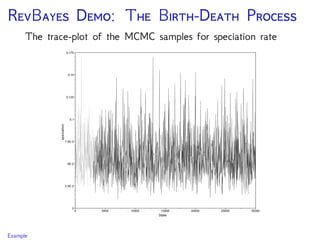

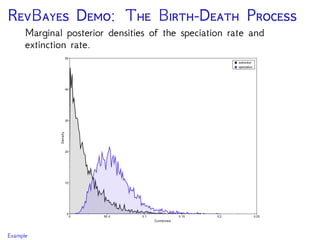

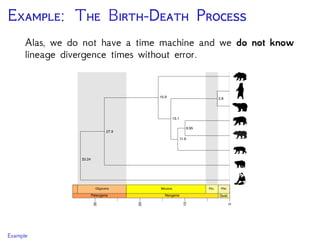

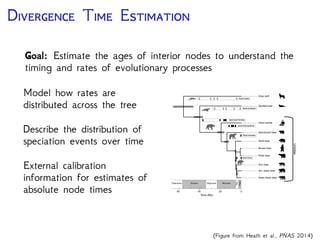

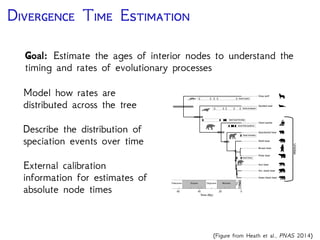

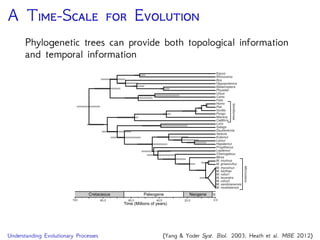

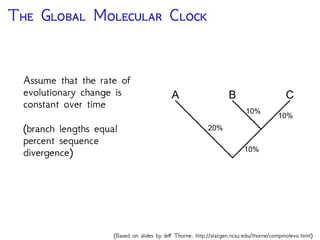

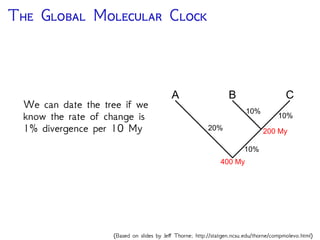

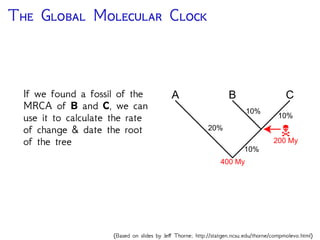

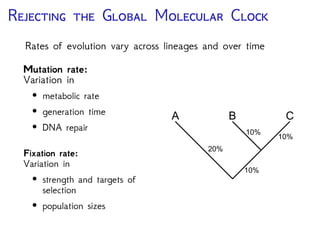

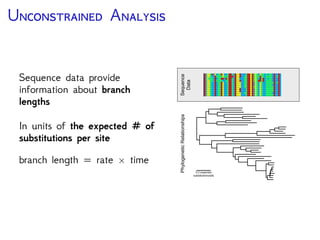

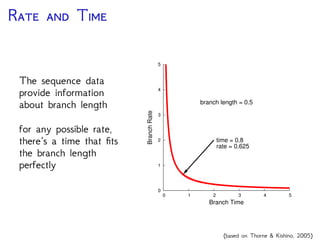

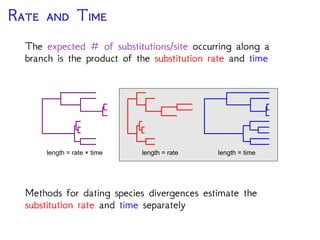

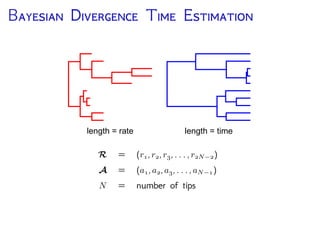

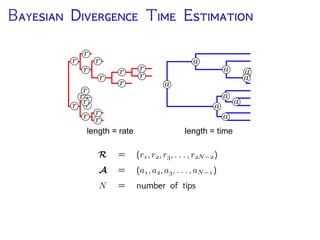

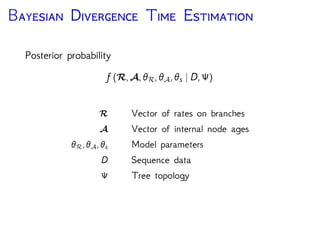

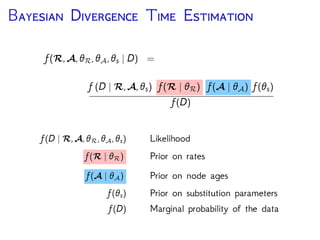

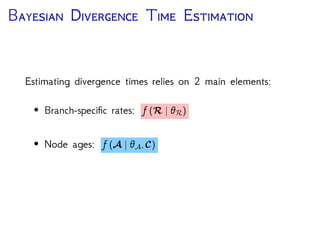

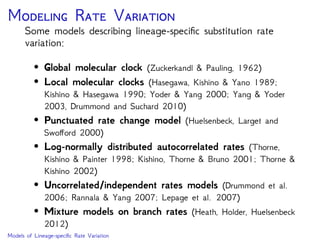

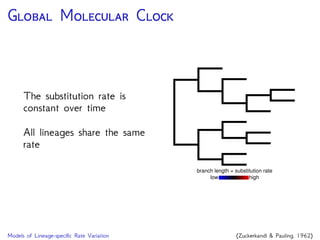

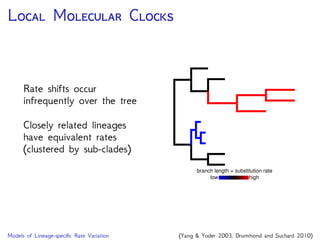

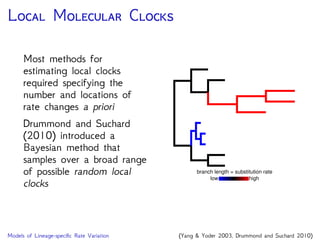

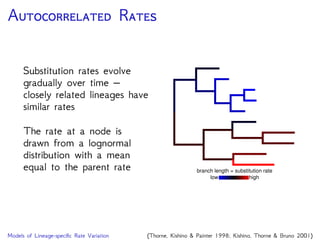

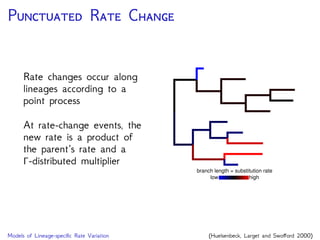

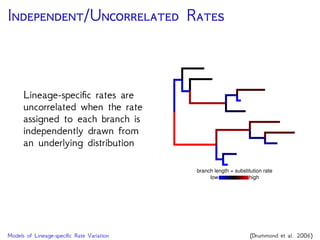

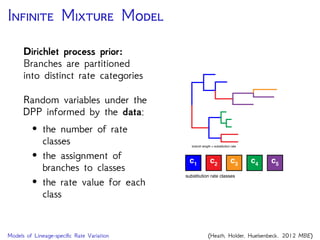

The document discusses Bayesian divergence time estimation in phylogenetics, focusing on Bayesian fundamentals, including Bayes' theorem, priors, and the birth-death process. It highlights the importance of relaxed clock models and MCMC methods for inferring species divergence times. Various tools, including RevBayes and graphical models, are introduced for visual representation and computational analysis of complex probabilistic models.

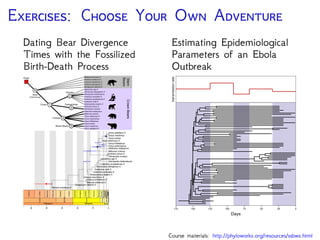

![M R V

Are our models appropriate across all data sets?

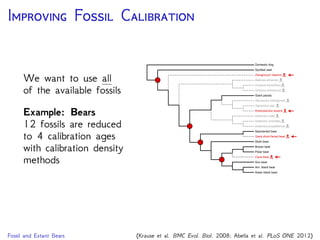

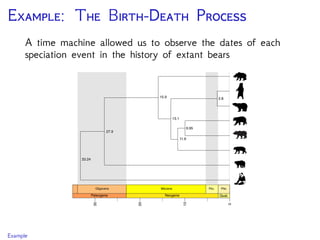

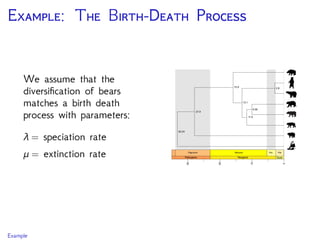

cave bear

American

black bear

sloth bear

Asian

black bear

brown bear

polar bear

American giant

short-faced bear

giant panda

sun bear

harbor seal

spectacled

bear

4.08

5.39

5.66

12.86

2.75

5.05

19.09

35.7

0.88

4.58

[3.11–5.27]

[4.26–7.34]

[9.77–16.58]

[3.9–6.48]

[0.66–1.17]

[4.2–6.86]

[2.1–3.57]

[14.38–24.79]

[3.51–5.89]

14.32

[9.77–16.58]

95% CI

mean age (Ma)

t2

t3

t4

t6

t7

t5

t8

t9

t10

tx

node

MP•MLu•MLp•Bayesian

100•100•100•1.00

100•100•100•1.00

85•93•93•1.00

76•94•97•1.00

99•97•94•1.00

100•100•100•1.00

100•100•100•1.00

100•100•100•1.00

t1

Eocene Oligocene Miocene Plio Plei Hol

34 5.3 1.823.8 0.01

Epochs

Ma

Global expansion of C4 biomass

Major temperature drop and increasing seasonality

Faunal turnover

Krause et al., 2008. Mitochondrial genomes reveal an

explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the

Miocene-Pliocene boundary. BMC Evol. Biol. 8.

Taxa

1

5

10

50

100

500

1000

5000

10000

20000

0100200300

MYA

Ophidiiformes

Percomorpha

Beryciformes

Lampriformes

Zeiforms

Polymixiiformes

Percopsif. + Gadiif.

Aulopiformes

Myctophiformes

Argentiniformes

Stomiiformes

Osmeriformes

Galaxiiformes

Salmoniformes

Esociformes

Characiformes

Siluriformes

Gymnotiformes

Cypriniformes

Gonorynchiformes

Denticipidae

Clupeomorpha

Osteoglossomorpha

Elopomorpha

Holostei

Chondrostei

Polypteriformes

Clade r ε ΔAIC

1. 0.041 0.0017 25.3

2. 0.081 * 25.5

3. 0.067 0.37 45.1

4. 0 * 3.1

Bg. 0.011 0.0011

OstariophysiAcanthomorpha

Teleostei

Santini et al., 2009. Did genome duplication drive the origin

of teleosts? A comparative study of diversification in

ray-finned fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 9.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bayesiandivtimessb-150520094854-lva1-app6892/85/Bayesian-Divergence-Time-Estimation-70-320.jpg)