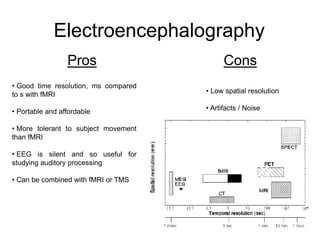

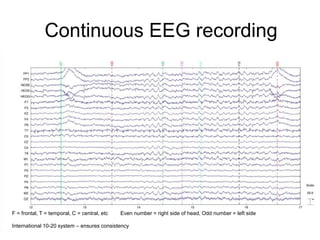

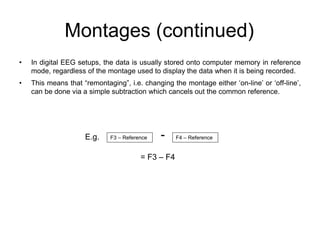

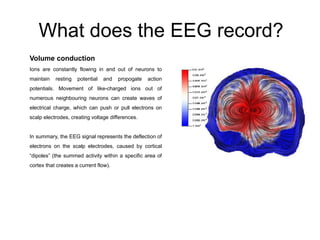

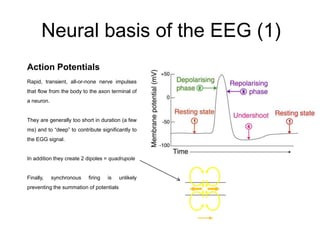

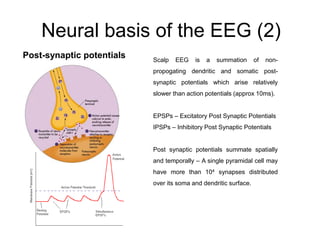

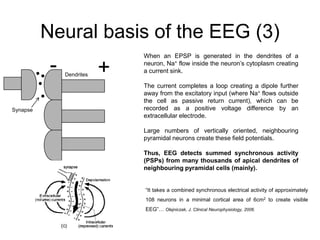

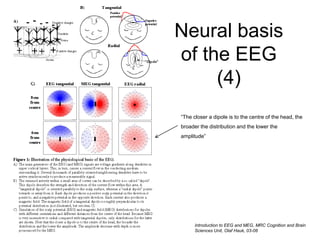

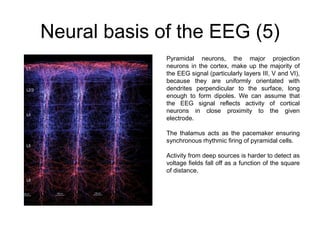

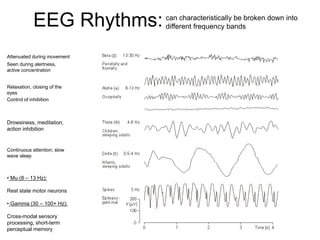

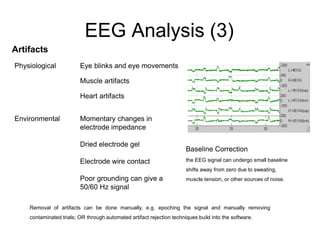

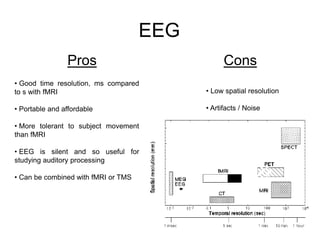

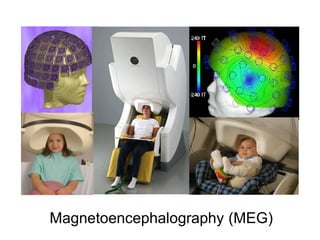

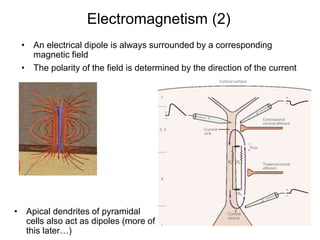

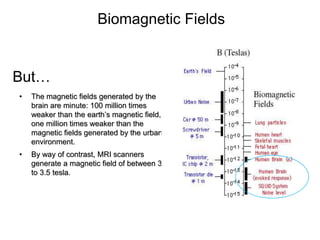

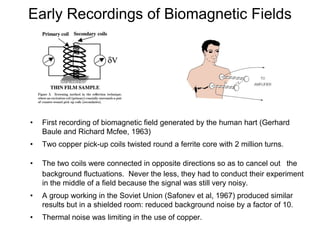

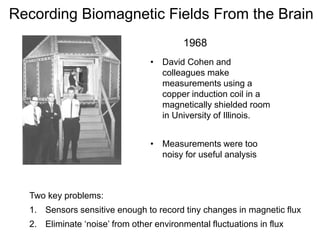

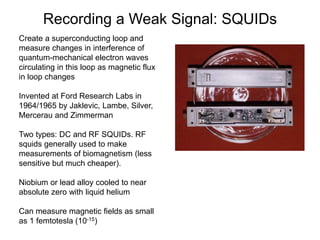

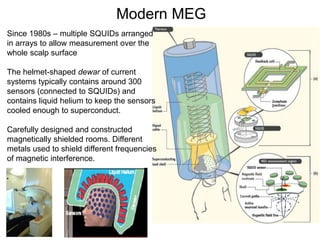

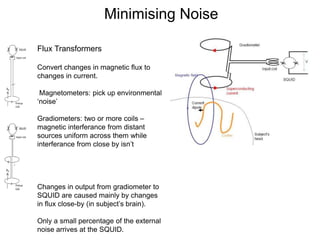

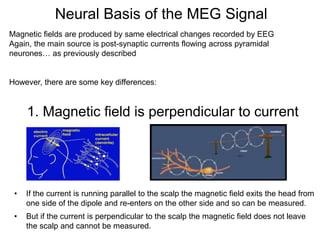

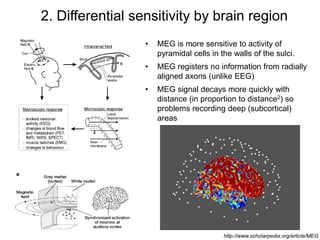

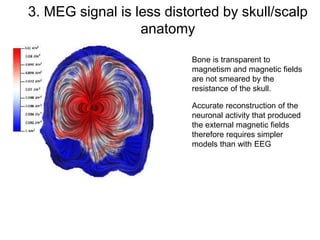

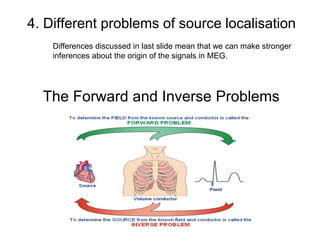

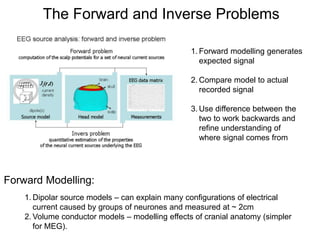

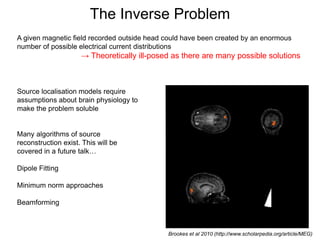

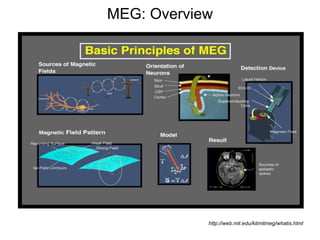

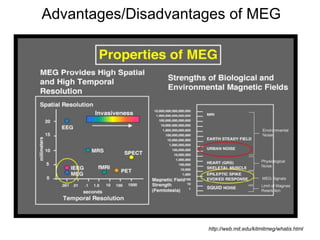

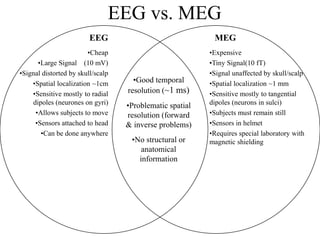

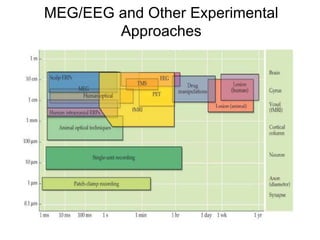

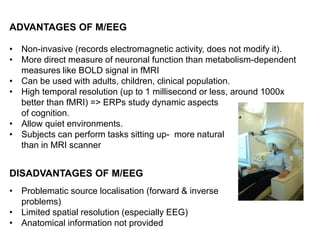

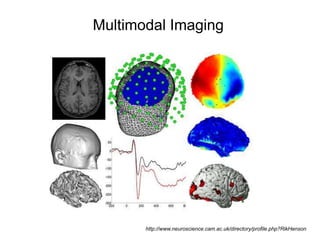

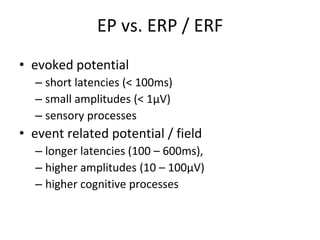

The document provides information on electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG). It discusses the history of EEG, how the signals are recorded, various montages used, neural basis of the signals, analysis methods for EEG including evoked potentials and artifacts. MEG is described as detecting the magnetic fields generated by electrical activity in the brain using SQUIDs, and its increased sensitivity to activity in sulcal walls compared to EEG. Key differences between the two methods are the orientation of measured fields relative to current flow in neurons.