This document contains information about WileyPLUS, an online learning environment for teaching and learning. It describes some of the key features of WileyPLUS, including interactive textbooks and resources, assignments, presentations, tutorials, technical and student support, and connections between instructors and students.

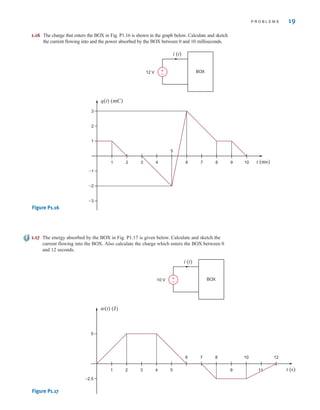

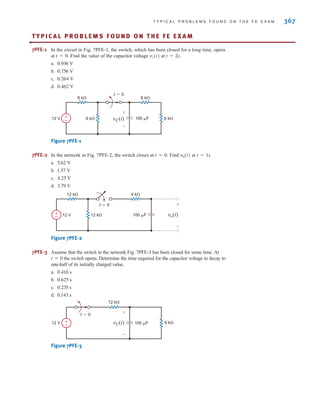

![The two types of current that we encounter often in our daily lives, alternating current (ac)

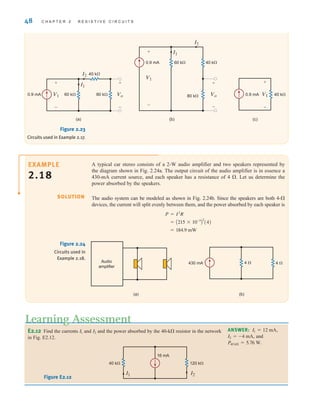

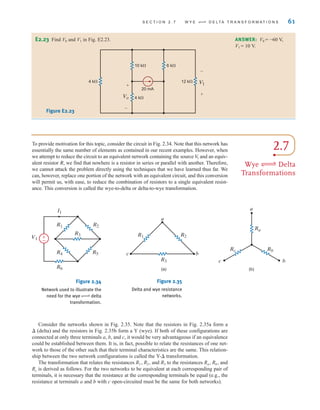

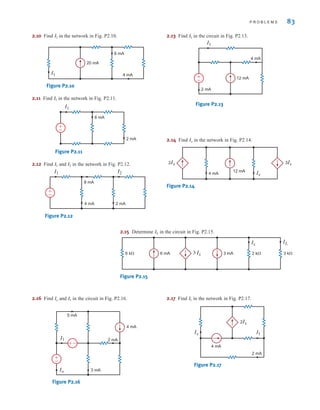

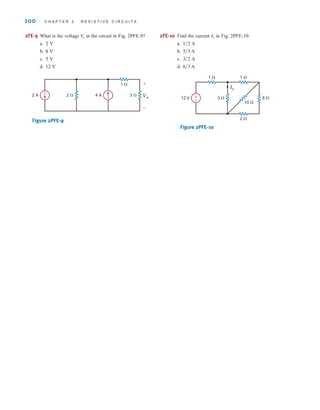

and direct current (dc), are shown as a function of time in Fig. 1.3. Alternating current is the

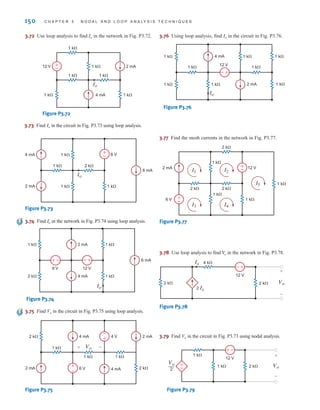

common current found in every household and is used to run the refrigerator, stove, washing

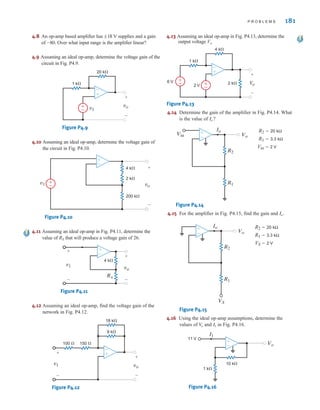

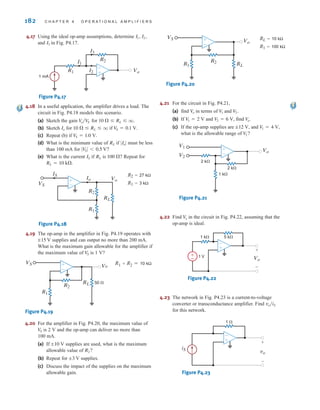

machine, and so on. Batteries, which are used in automobiles and flashlights, are one source

of direct current. In addition to these two types of currents, which have a wide variety of uses,

we can generate many other types of currents. We will examine some of these other types

later in the book. In the meantime, it is interesting to note that the magnitude of currents in

elements familiar to us ranges from soup to nuts, as shown in Fig. 1.4.

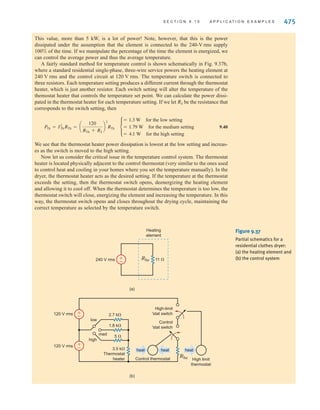

We have indicated that charges in motion yield an energy transfer. Now we define the

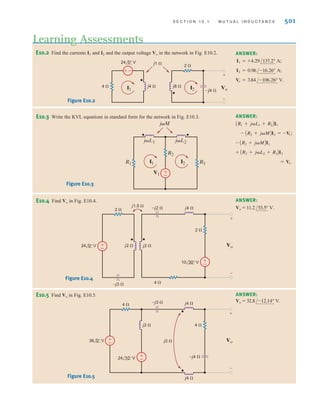

voltage (also called the electromotive force, or potential) between two points in a circuit as the

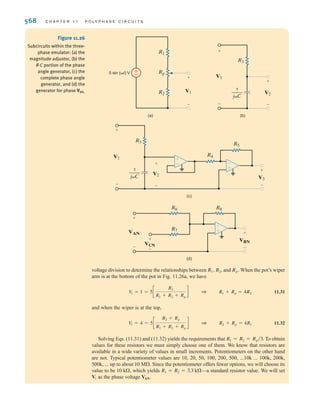

difference in energy level of a unit charge located at each of the two points. Voltage is very sim-

ilar to a gravitational force. Think about a bowling ball being dropped from a ladder into a tank

of water. As soon as the ball is released, the force of gravity pulls it toward the bottom of the

tank. The potential energy of the bowling ball decreases as it approaches the bottom. The grav-

itational force is pushing the bowling ball through the water. Think of the bowling ball as a

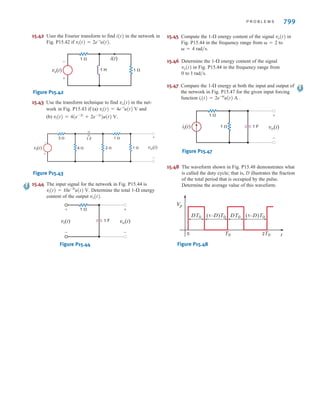

charge and the voltage as the force pushing the charge through a circuit. Charges in motion

represent a current, so the motion of the bowling ball could be thought of as a current. The

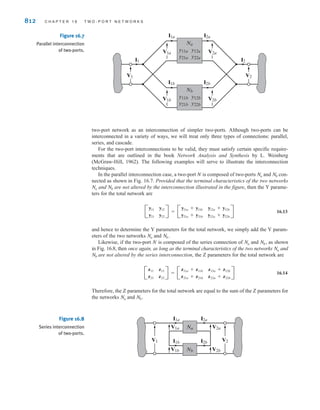

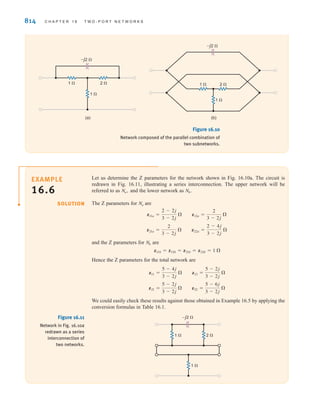

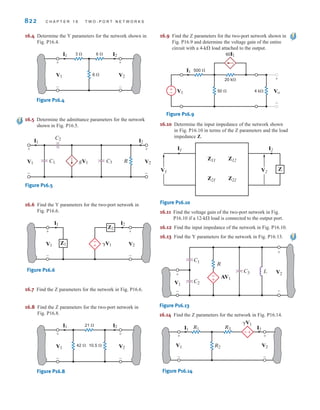

water in the tank will resist the motion of the bowling ball. The motion of charges in an elec-

tric circuit will be impeded or resisted as well. We will introduce the concept of resistance in

Chapter 2 to describe this effect.

Work or energy, w(t) or W, is measured in joules (J); 1 joule is 1 newton meter (N⭈m).

Hence, voltage [v(t) or V] is measured in volts (V) and 1 volt is 1 joule per coulomb; that is,

1 volt=1 joule per coulomb=1 newton meter per coulomb. If a unit positive charge is

moved between two points, the energy required to move it is the difference in energy level

between the two points and is the defined voltage. It is extremely important that the variables

used to represent voltage between two points be defined in such a way that the solution will

let us interpret which point is at the higher potential with respect to the other.

S E C T I O N 1 . 2 B A S I C Q U A N T I T I E S 3

Figure 1.3

Two common types

of current: (a) alternating

current (ac); (b) direct

current (dc).

i(t)

t t

i(t)

(a) (b)

Figure 1.4

Typical current magnitudes.

Lightning bolt

Large industrial motor current

Typical household appliance current

Causes ventricular fibrillation in humans

Human threshold of sensation

Integrated circuit (IC) memory cell current

Synaptic current (brain cell)

106

104

102

100

10–2

10–4

10–6

10–8

10–10

10–12

10–14

Current

in

amperes

(A)

irwin01_001-024hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:16 Page 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-27-320.jpg)

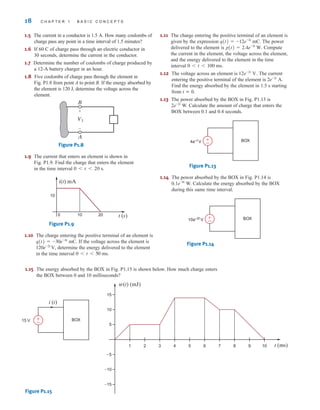

![6 C H A P T E R 1 B A S I C C O N C E P T S

Suppose that your car will not start. To determine whether the battery is faulty, you turn on

the light switch and find that the lights are very dim, indicating a weak battery. You borrow

a friend’s car and a set of jumper cables. However, how do you connect his car’s battery to

yours? What do you want his battery to do?

Essentially, his car’s battery must supply energy to yours, and therefore it should be

connected in the manner shown in Fig. 1.10. Note that the positive current leaves the posi-

tive terminal of the good battery (supplying energy) and enters the positive terminal of the

weak battery (absorbing energy). Note that the same connections are used when charging a

battery.

EXAMPLE

1.1

SOLUTION

I

I

Good

battery

Weak

battery

+ – + –

Figure 1.10

Diagram for Example 1.1.

In practical applications there are often considerations other than simply the electrical

relations (e.g., safety). Such is the case with jump-starting an automobile. Automobile

batteries produce explosive gases that can be ignited accidentally, causing severe physical

injury. Be safe—follow the procedure described in your auto owner’s manual.

We have defined voltage in joules per coulomb as the energy required to move a positive

charge of 1 C through an element. If we assume that we are dealing with a differential amount

of charge and energy, then

1.2

Multiplying this quantity by the current in the element yields

1.3

which is the time rate of change of energy or power measured in joules per second, or watts

(W). Since, in general, both v and i are functions of time, p is also a time-varying quantity.

Therefore, the change in energy from time to time can be found by integrating Eq. (1.3);

that is,

1.4

At this point, let us summarize our sign convention for power. To determine the sign of

any of the quantities involved, the variables for the current and voltage should be arranged as

shown in Fig. 1.11. The variable for the voltage v(t) is defined as the voltage across the ele-

ment with the positive reference at the same terminal that the current variable i(t) is entering.

This convention is called the passive sign convention and will be so noted in the remainder

of this book. The product of v and i, with their attendant signs, will determine the magnitude

and sign of the power. If the sign of the power is positive, power is being absorbed by the ele-

ment; if the sign is negative, power is being supplied by the element.

¢w =

3

t2

t1

p dt =

3

t2

t1

vi dt

t2

t1

vi =

dw

dq

a

dq

dt

b =

dw

dt

= p

v =

dw

dq

i(t)

v(t)

+

–

The passive sign convention

is used to determine whether

power is being absorbed or

supplied.

[ h i n t ]

Figure 1.11

Sign convention for power.

irwin01_001-024hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:16 Page 6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-30-320.jpg)

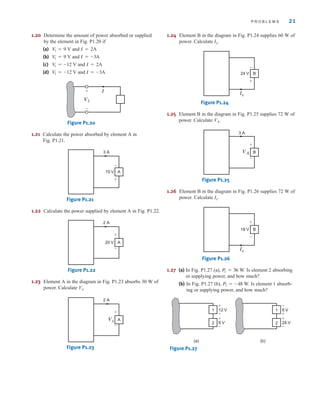

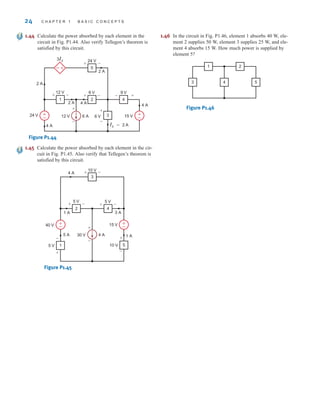

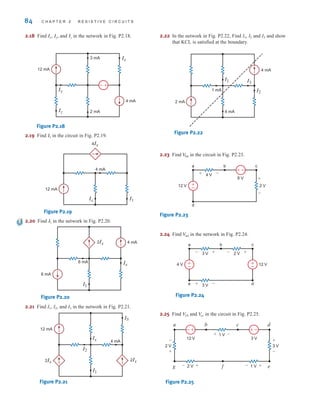

![DEPENDENT SOURCES In contrast to the independent sources, which produce a

particular voltage or current completely unaffected by what is happening in the remainder of

the circuit, dependent sources generate a voltage or current that is determined by a voltage or

current at a specified location in the circuit. These sources are very important because they

are an integral part of the mathematical models used to describe the behavior of many elec-

tronic circuit elements.

For example, metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) and bipolar

transistors, both of which are commonly found in a host of electronic equipment, are mod-

eled with dependent sources, and therefore the analysis of electronic circuits involves the use

of these controlled elements.

In contrast to the circle used to represent independent sources, a diamond is used to

represent a dependent or controlled source. Fig. 1.16 illustrates the four types of dependent

sources. The input terminals on the left represent the voltage or current that controls the

dependent source, and the output terminals on the right represent the output current or volt-

age of the controlled source. Note that in Figs. 1.16a and d, the quantities and  are dimen-

sionless constants because we are transforming voltage to voltage and current to current. This

is not the case in Figs. 1.16b and c; hence, when we employ these elements a short time later,

we must describe the units of the factors r and g.

10 C H A P T E R 1 B A S I C C O N C E P T S

The current flow is out of the positive terminal of the 24-V source, and therefore this

element is supplying (2)(24)=48 W of power. The current is into the positive terminals

of elements 1 and 2, and therefore elements 1 and 2 are absorbing (2)(6)=12 W and

(2)(18)=36 W, respectively. Note that the power supplied is equal to the power

absorbed.

SOLUTION

+

–

+

–

v=vS

+

–

+

–

(a) (b)

vS

vS i=gvS

v=riS

i=iS

iS

(c) (d)

iS

Figure 1.16

Four different types of

dependent sources.

Elements that are

connected in series have

the same current.

[ h i n t ]

E1.3 Find the power that is absorbed or supplied by the elements in Fig. E1.3.

Learning Assessment

ANSWER: Current source

supplies 36 W, element

1 absorbs 54 W, and

element 2 supplies 18 W.

Figure E1.3

12 V 6 V

I=3 A

3 A

I=3 A

+

+

–

–

+

–

18 V

2

1

irwin01_001-024hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:16 Page 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-34-320.jpg)

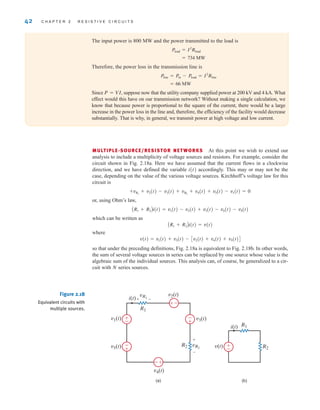

![26 C H A P T E R 2 R E S I S T I V E C I R C U I T S

2.1

Ohm’s Law

Ohm’s law is named for the German physicist Georg Simon Ohm, who is credited with

establishing the voltage–current relationship for resistance. As a result of his pioneering

work, the unit of resistance bears his name.

Ohm’s law states that the voltage across a resistance is directly proportional to the current

flowing through it. The resistance, measured in ohms, is the constant of proportionality

between the voltage and current.

A circuit element whose electrical characteristic is primarily resistive is called a resistor

and is represented by the symbol shown in Fig. 2.1a. A resistor is a physical device that can

be purchased in certain standard values in an electronic parts store. These resistors, which

find use in a variety of electrical applications, are normally carbon composition or wire-

wound. In addition, resistors can be fabricated using thick oxide or thin metal films for use

in hybrid circuits, or they can be diffused in semiconductor integrated circuits. Some typical

discrete resistors are shown in Fig. 2.1b.

The mathematical relationship of Ohm’s law is illustrated by the equation

v(t)=R i(t), where R ⭌ 0 2.1

or equivalently, by the voltage–current characteristic shown in Fig. 2.2a. Note carefully the

relationship between the polarity of the voltage and the direction of the current. In addition,

note that we have tacitly assumed that the resistor has a constant value and therefore that the

voltage–current characteristic is linear.

The symbol ⍀ is used to represent ohms, and therefore,

1 ⍀=1 V/A

Although in our analysis we will always assume that the resistors are linear and are thus

described by a straight-line characteristic that passes through the origin, it is important that

readers realize that some very useful and practical elements do exist that exhibit a nonlinear

resistance characteristic; that is, the voltage–current relationship is not a straight line.

R

i(t)

v(t)

+

–

(a) (b)

Figure 2.1

(a) Symbol for a resistor;

(b) some practical devices.

(1), (2), and (3) are high-

power resistors. (4) and (5)

are high-wattage fixed

resistors. (6) is a high-

precision resistor. (7)–(12)

are fixed resistors with

different power ratings.

(Photo courtesy of Mark

Nelms and Jo Ann Loden)

The passive sign convention

will be employed in

conjunction with Ohm’s law.

[ h i n t ]

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 22-07-2010 15:03 Page 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-50-320.jpg)

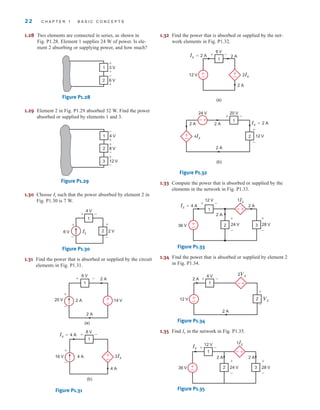

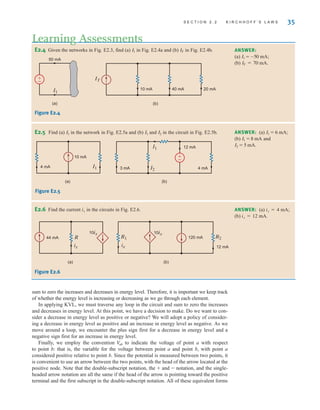

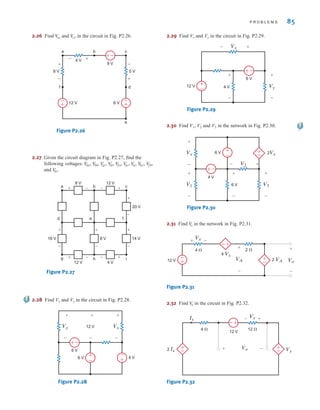

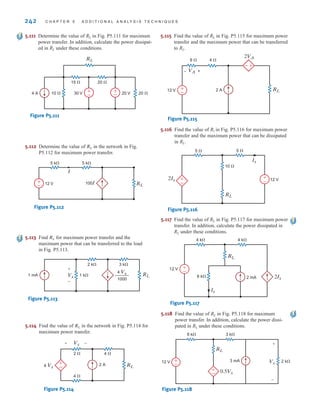

![in Fig. 2.5a will be used to describe the terms node, loop, and branch. A node is simply a

point of connection of two or more circuit elements. The reader is cautioned to note that,

although one node can be spread out with perfect conductors, it is still only one node. This

is illustrated in Fig. 2.5b, where the circuit has been redrawn. Node 5 consists of the entire

bottom connector of the circuit.

If we start at some point in the circuit and move along perfect conductors in any direction

until we encounter a circuit element, the total path we cover represents a single node.

Therefore, we can assume that a node is one end of a circuit element together with all the per-

fect conductors that are attached to it. Examining the circuit, we note that there are numerous

paths through it. A loop is simply any closed path through the circuit in which no node

is encountered more than once. For example, starting from node 1, one loop would contain the

elements and i1; another loop would contain and i1; and so on.

However, the path and i1 is not a loop because we have encountered node 3

twice. Finally, a branch is a portion of a circuit containing only a single element and the nodes

at each end of the element. The circuit in Fig. 2.5 contains eight branches.

Given the previous definitions, we are now in a position to consider Kirchhoff’s laws,

named after German scientist Gustav Robert Kirchhoff. These two laws are quite simple but

extremely important. We will not attempt to prove them because the proofs are beyond our

current level of understanding. However, we will demonstrate their usefulness and attempt to

make the reader proficient in their use. The first law is Kirchhoff’s current law (KCL), which

states that the algebraic sum of the currents entering any node is zero. In mathematical form

the law appears as

2.7

a

N

j=1

ij(t) = 0

R1, v1, R5, v2, R3,

R2, v1, v2, R4,

R1, v2, R4,

S E C T I O N 2 . 2 K I R C H H O F F ’ S L A W S 31

i1(t)

v2(t)

v1(t)

R1

R2

R5

R4

R3

(a)

R2

i1(t)

i2(t) i3(t)

i5(t)

v1(t)

v2(t)

i7(t)

i4(t)

i6(t)

i8(t)

R1

R4 R5

(b)

1

4

5

2

3

R3

–

±

±

–

±

–

–

±

Figure 2.5

Circuit used to illustrate KCL.

KCL is an extremely important

and useful law.

[ h i n t ]

2.2

Kirchhoff’s Laws

The circuits we have considered previously have all contained a single resistor, and we have

analyzed them using Ohm’s law. At this point we begin to expand our capabilities to handle

more complicated networks that result from an interconnection of two or more of these sim-

ple elements. We will assume that the interconnection is performed by electrical conductors

(wires) that have zero resistance—that is, perfect conductors. Because the wires have zero

resistance, the energy in the circuit is in essence lumped in each element, and we employ the

term lumped-parameter circuit to describe the network.

To aid us in our discussion, we will define a number of terms that will be employed

throughout our analysis. As will be our approach throughout this text, we will use examples

to illustrate the concepts and define the appropriate terms. For example, the circuit shown

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-55-320.jpg)

![for labeling voltages are shown in Fig. 2.11. The usefulness of the arrow notation stems from

the fact that we may want to label the voltage between two points that are far apart in a

network. In this case, the other notations are often confusing.

In general, the mathematical representation of Kirchhoff’s voltage law is

2.8

where vj(t) is the voltage across the jth branch (with the proper reference direction) in a loop

containing N voltages. This expression is analogous to Eq. (2.7) for Kirchhoff’s current law.

a

N

j=1

vj(t) = 0

S E C T I O N 2 . 2 K I R C H H O F F ’ S L A W S 37

1 1

(a)

Vx=Vab

a

b

+

–

1

a

b

+

–

1

Vx=Vo

+

–

Vx=Vo

+

–

Vo

(b)

Vx=Vab=Vo

(d)

Vo

+

–

Vo

+

–

(c)

Vo

Figure 2.11

Equivalent forms for labeling

voltage.

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

2.11

Consider the network in Fig. 2.12a. Let us apply KVL to determine the voltage between two

points. Specifically, in terms of the double-subscript notation, let us find and V

ec.

V

ae

The circuit is redrawn in Fig. 2.12b. Since points a and e as well as e and c are not physi-

cally close, the arrow notation is very useful. Our approach to determining the unknown

voltage is to apply KVL with the unknown voltage in the closed path. Therefore, to deter-

mine we can use the path aefa or abcdea. The equations for the two paths in which

is the only unknown are

and

Note that both equations yield Even before calculating we could calculate

using the path cdec or cefabc. However, since is now known, we can also use the path

ceabc. KVL for each of these paths is

and

Each of these equations yields V

ec = -10 V.

-V

ec - V

ae + 16 - 12 = 0

-V

ec + 10 - 24 + 16 - 12 = 0

4 + 6 + V

ec = 0

V

ae

V

ec

V

ae,

V

ae = 14 V.

16 - 12 + 4 + 6 - V

ae = 0

Vae + 10 - 24 = 0

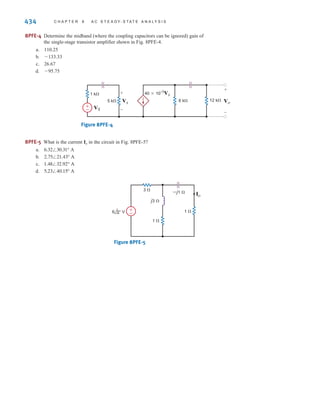

V

ae

V

ae

Vae Vec

(a) (b)

R1

R4 R3

R2

24 V

16 V

6 V

10 V

+ +

–

–

–

+

+

–

12 V

4 V

f d

b

e

a c

24 V

16 V

6 V

10 V

+ +

–

–

–

+

+

–

12 V

4 V

f d

b

e

a c

±

–

+

-

±

–

+

-

Figure 2.12

Network used in

Example 2.11.

KVL is an extremely important

and useful law.

[ h i n t ]

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 2 . 3 S I N G L E - L O O P C I R C U I T S 39

Before proceeding with the analysis of simple circuits, it is extremely important that we

emphasize a subtle but very critical point. Ohm’s law as defined by the equation V=IR

refers to the relationship between the voltage and current as defined in Fig. 2.14a. If the direc-

tion of either the current or the voltage, but not both, is reversed, the relationship between the

current and the voltage would be V=–IR. In a similar manner, given the circuit in

Fig. 2.14b, if the polarity of the voltage between the terminals A and B is specified as shown,

then the direction of the current I is from point B through R to point A. Likewise, in

Fig. 2.14c, if the direction of the current is specified as shown, then the polarity of the voltage

must be such that point D is at a higher potential than point C and, therefore, the arrow rep-

resenting the voltage V is from point C to point D.

The subtleties associated

with Ohm’s law, as described

here, are important and must

be adhered to in order to

ensure that the variables

have the proper sign.

[ h i n t ]

(a) (b) (c)

V

I

R

A

B

+

–

V

I

R

A

B

-

+

V

I

R

C D

Figure 2.14

Circuits used to explain

Ohm’s law.

2.3

Single-Loop

Circuits

VOLTAGE DIVISION At this point we can begin to apply the laws presented earlier to the

analysis of simple circuits. To begin, we examine what is perhaps the simplest circuit—a

single closed path, or loop, of elements.

Applying KCL to every node in a single-loop circuit reveals that the same current flows

through all elements. We say that these elements are connected in series because they carry

the same current. We will apply Kirchhoff’s voltage law and Ohm’s law to the circuit to

determine various quantities in the circuit.

Our approach will be to begin with a simple circuit and then generalize the analysis to more

complicated ones. The circuit shown in Fig. 2.15 will serve as a basis for discussion. This cir-

cuit consists of an independent voltage source that is in series with two resistors. We have

assumed that the current flows in a clockwise direction. If this assumption is correct, the

solution of the equations that yields the current will produce a positive value. If the current is

actually flowing in the opposite direction, the value of the current variable will simply be

negative, indicating that the current is flowing in a direction opposite to that assumed. We have

also made voltage polarity assignments for and These assignments have been made

using the convention employed in our discussion of Ohm’s law and our choice for the direc-

tion of i(t)—that is, the convention shown in Fig. 2.14a.

Applying Kirchhoff’s voltage law to this circuit yields

or

However, from Ohm’s law we know that

Therefore,

v(t)=R1i(t)+R2i(t)

Solving the equation for i(t) yields

2.9

i(t) =

v(t)

R1 + R2

vR2

= R2i(t)

vR1

= R1i(t)

v(t) = vR1

+ vR2

-v(t) + vR1

+ vR2

= 0

vR2

.

vR1

±

–

vR1

vR2

R1

R2

v(t)

i(t)

+

–

+

–

Figure 2.15

Single-loop circuit.

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-63-320.jpg)

![Knowing the current, we can now apply Ohm’s law to determine the voltage across each

resistor:

2.10

Similarly,

2.11

Though simple, Eqs. (2.10) and (2.11) are very important because they describe the oper-

ation of what is called a voltage divider. In other words, the source voltage v(t) is divided

between the resistors and in direct proportion to their resistances.

In essence, if we are interested in the voltage across the resistor we bypass the calcu-

lation of the current i(t) and simply multiply the input voltage v(t) by the ratio

As illustrated in Eq. (2.10), we are using the current in the calculation, but not explicitly.

Note that the equations satisfy Kirchhoff’s voltage law, since

-v(t) +

R1

R1 + R2

v(t) +

R2

R1 + R2

v(t) = 0

R1

R1 + R2

R1,

R2

R1

vR2

=

R2

R1 + R2

v(t)

=

R1

R1 + R2

v(t)

= R1 c

v(t)

R1 + R2

d

vR1

= R1i(t)

40 C H A P T E R 2 R E S I S T I V E C I R C U I T S

Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 2.16. The circuit is identical to Fig. 2.15 except that

is a variable resistor such as the volume control for a radio or television set. Suppose that

and R2 = 30 k.

R1 = 90 k,

V

S = 9 V,

R1

EXAMPLE

2.13

SOLUTION

VS

V2

R1

I

R2

+

–

±

–

Figure 2.16

Voltage-divider circuit.

Let us examine the change in both the voltage across and the power absorbed in this

resistor as is changed from 90 k to 15 k.

Since this is a voltage-divider circuit, the voltage can be obtained directly as

= 2.25 V

= c

30k

90k + 30k

d (9)

V2 = c

R2

R1 + R2

d V

S

V

2

R1

R2

The manner in which voltage

divides between two

series resistors.

[ h i n t ]

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-64-320.jpg)

![where

2.16

2.17

Therefore, the equivalent resistance of two resistors connected in parallel is equal to the

product of their resistances divided by their sum. Note also that this equivalent resistance

is always less than either or Hence, by connecting resistors in parallel we reduce the

overall resistance. In the special case when the equivalent resistance is equal to half

of the value of the individual resistors.

The manner in which the current i(t) from the source divides between the two branches

is called current division and can be found from the preceding expressions. For example,

2.18

=

R1R2

R1 + R2

i(t)

v(t) = Rpi(t)

R1 = R2,

R2.

R1

Rp

Rp =

R1R2

R1 + R2

1

Rp

=

1

R1

+

1

R2

46 C H A P T E R 2 R E S I S T I V E C I R C U I T S

The parallel resistance

equation.

[ h i n t ]

CURRENT DIVISION An important circuit is the single-node-pair circuit. If we apply KVL to

every loop in a single-node-pair circuit, we discover that all of the elements have the same volt-

age across them and, therefore, are said to be connected in parallel. We will, however, apply

Kirchhoff’s current law and Ohm’s law to determine various unknown quantities in the circuit.

Following our approach with the single-loop circuit, we will begin with the simplest case

and then generalize our analysis. Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 2.22. Here we have an

independent current source in parallel with two resistors.

R2

R1 v(t)

i(t)

i1(t) i2(t)

+

–

Figure 2.22

Simple parallel circuit.

Since all of the circuit elements are in parallel, the voltage v(t) appears across each of

them. Furthermore, an examination of the circuit indicates that the current i(t) is into the

upper node of the circuit and the currents i1(t) and i2(t) are out of the node. Since KCL

essentially states that what goes in must come out, the question we must answer is how i1(t)

and i2(t) divide the input current i(t).

Applying Kirchhoff’s current law to the upper node, we obtain

i(t)=i1(t)+i2(t)

and, employing Ohm’s law, we have

=

v(t)

Rp

= a

1

R1

+

1

R2

bv(t)

i(t) =

v(t)

R1

+

v(t)

R2

2.4

Single-Node-Pair

Circuits

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-70-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 2 . 4 S I N G L E - N O D E - P A I R C I R C U I T S 47

The manner in which

current divides between

two parallel resistors.

[ h i n t ]

Given the network in Fig. 2.23a, let us find and

First, it is important to recognize that the current source feeds two parallel paths. To empha-

size this point, the circuit is redrawn as shown in Fig. 2.23b. Applying current division,

we obtain

and

Note that the larger current flows through the smaller resistor, and vice versa. In addition,

note that if the resistances of the two paths are equal, the current will divide equally between

them. KCL is satisfied since I1+I2=0.9 mA.

The voltage can be derived using Ohm’s law as

The problem can also be approached in the following manner. The total resistance seen by

the current source is 40 k, that is, 60 k in parallel with the series combination of 40 k

and 80 k, as shown in Fig. 2.23c. The voltage across the current source is then

Now that is known, we can apply voltage division to find Vo:

= 24 V

= a

80k

120k

b36

V

o = a

80k

80k + 40k

bV

1

V

1

= 36 V

V

1 = A0.9 * 10-3

B40k

= 24 V

V

o = 80kI2

V

o

= 0.3 mA

I2 = c

60k

60k + (40k + 80k)

d A0.9 * 10-3

B

= 0.6 mA

I1 = c

40k + 80k

60k + (40k + 80k)

d A0.9 * 10-3

B

Vo.

I1, I2,

and

2.19

and

2.20

Eqs. (2.19) and (2.20) are mathematical statements of the current-division rule.

=

R1

R1 + R2

i(t)

i2(t) =

v(t)

R2

i1(t) =

R2

R1 + R2

i(t)

i1(t) =

v(t)

R1

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

2.17

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-71-320.jpg)

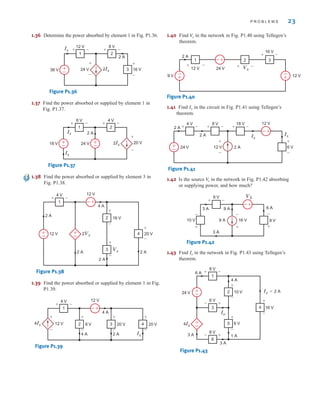

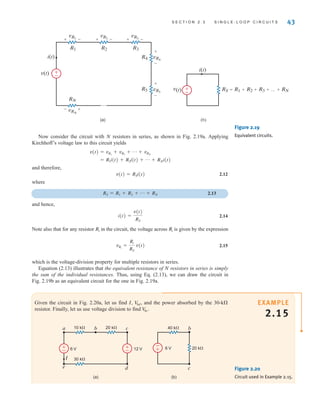

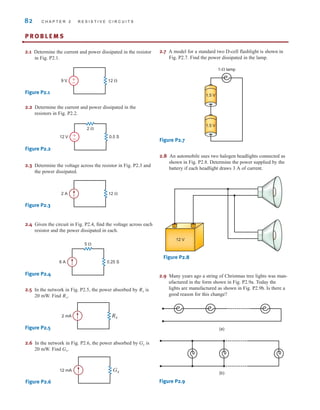

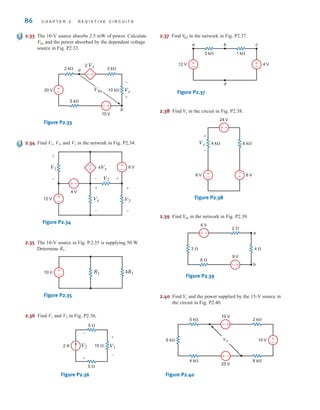

![S E C T I O N 2 . 1 1 D E S I G N E X A M P L E S 77

Rearranging the equation yields

A second expression involving and can be developed by considering the case when

are all on, which causes to reach its minimum value of 9–5%, or 8.55 V. Now, the

effective resistance of the lamps is five 1.8- resistors in parallel, or The corre-

sponding expression for is

which can be rewritten in the form

Substituting the value determined for into the preceding equation yields

or

and so for

R2 = 178.3

R2

R1 = 48.1

R1 = 360[1.4 - 1 - 0.27]

R1兾R2

360R1

R2

+ 360 + R1

360

=

12

8.55

= 1.4

V2 = 8.55 = 12c

R2兾兾360

R1 + AR2兾兾360B

d

V

2

360 .

k

V

2

L3–L7

R2

R1

R1

R2

= 0.27

•

DESIGN

EXAMPLE 2.35

•

DESIGN

EXAMPLE 2.35

SOLUTION

Let’s design a circuit that produces a 5-V output from a 12-V input. We will arbitrarily fix

the power consumed by the circuit at 240 mW. Finally, we will choose the best possible

standard resistor values from Table 2.1 and calculate the percent error in the output voltage

that results from that choice.

The simple voltage divider, shown in Fig. 2.50, is ideally suited for this application. We

know that is given by

which can be written as

Since all of the circuit’s power is supplied by the 12-V source, the total power is given by

Using the second equation to eliminate we find that has a lower limit of

Substituting these results into the second equation yields the lower limit of that is

Thus, we find that a significant portion of Table 2.1 is not applicable to this design.

However, determining the best pair of resistor values is primarily a trial-and-error operation

R1 = R2 c

V

in

V

o

- 1d 350

R1,

R2

V

oV

in

P

=

(5)(12)

0.24

= 250

R2

R1,

P =

V2

in

R1 + R2

0.24

R1 = R2 c

V

in

V

o

- 1d

V

o = V

in c

R2

R1 + R2

d

V

o

R1

12 V

R2 Vo=5 V

+

-

±

–

Figure 2.50

A simple voltage divider

irwin02_025-100hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:14 Page 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-101-320.jpg)

![The voltage is the voltage at node 1 with respect to the reference node 3.

Similarly, the voltage is the voltage at node 2 with respect to node 3. In addition,

however, the voltage at node 1 with respect to node 2 is ±6 V, and the voltage at node 2 with

respect to node 1 is -6 V. Furthermore, since the current will flow from the node of higher

potential to the node of lower potential, the current in is from top to bottom, the current

in is from left to right, and the current in is from bottom to top.

These concepts have important ramifications in our daily lives. If a man were hanging in

midair with one hand on one line and one hand on another and the dc line voltage of each

line was exactly the same, the voltage across his heart would be zero and he would be safe.

If, however, he let go of one line and let his feet touch the ground, the dc line voltage would

then exist from his hand to his foot with his heart in the middle. He would probably be dead

the instant his foot hit the ground.

In the town where we live, a young man tried to retrieve his parakeet that had escaped its

cage and was outside sitting on a power line. He stood on a metal ladder and with a metal

pole reached for the parakeet; when the metal pole touched the power line, the man was killed

instantly. Electric power is vital to our standard of living, but it is also very dangerous. The

material in this book does not qualify you to handle it safely. Therefore, always be extreme-

ly careful around electric circuits.

Now as we begin our discussion of nodal analysis, our approach will be to begin with sim-

ple cases and proceed in a systematic manner to those that are more challenging. Numerous

examples will be the vehicle used to demonstrate each facet of this approach. Finally, at the

end of this section, we will outline a strategy for attacking any circuit using nodal analysis.

CIRCUITS CONTAINING ONLY INDEPENDENT CURRENT SOURCES Consider

the network shown in Fig. 3.4. Note that this network contains three nodes, and thus we know

that exactly linearly independent KCL equations will be required to

determine the unknown node voltages. First, we select the bottom node as the

reference node, and then the voltage at the two remaining nodes labeled and will be

measured with respect to this node.

The branch currents are assumed to flow in the directions indicated in the figures. If one

or more of the branch currents are actually flowing in a direction opposite to that assumed,

the analysis will simply produce a branch current that is negative.

Applying KCL at node 1 yields

Using Ohm’s law (i=Gv) and noting that the reference node is at zero potential, we obtain

or

KCL at node 2 yields

or

which can be expressed as

-G2v1 + AG2 + G3Bv2 = -iB

-G2Av1 - v2B + iB + G3Av2 - 0B = 0

-i2 + iB + i3 = 0

AG1 + G2Bv1 - G2v2 = iA

-iA + G1Av1 - 0B + G2Av1 - v2B = 0

-iA + i1 + i2 = 0

v2

v1

N - 1 = 2

N - 1 = 3 - 1 = 2

R3

R2

R1

V

2 = -2 V

V

1 = 4 V

104 C H A P T E R 3 N O D A L A N D L O O P A N A LY S I S T E C H N I Q U E S

Employing the passive sign

convention.

[ h i n t ]

1 2

3

R1 R3

R2

iB

i3

i1

i2

iA

v1 v2

Figure 3.4

A three-node circuit.

irwin03_101-155hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:12 Page 104](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-128-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 3 . 1 N O D A L A N A LY S I S 113

E3.4 Find the node voltages in the circuit in Fig. E3.4.

Learning Assessments

ANSWER:

V2 = -8 V.

V

1 = 16 V,

E3.5 Find the voltage in the network in Fig. E3.5.

Vo ANSWER: Vo = 4 V.

4 mA

10 k⍀

10 k⍀

10 k⍀

Io

2Io

V1 V2

Figure E3.4

3 k⍀

2 mA 12 k⍀ 12 k⍀ Vo

+

-

Vx

6000

—

Vx

Figure E3.5

2 mA

6 k⍀

3 k⍀ 6 k⍀

2IA 1 k⍀

2 k⍀

Vo

+

–

IA

E3.6 Find in Fig. E3.6 using nodal analysis.

V

o ANSWER: = 0.952 V.

Vo

Figure E3.6

CIRCUITS CONTAINING INDEPENDENT VOLTAGE SOURCES As is our practice,

in our discussion of this topic we will proceed from the simplest case to more complicated

cases. The simplest case is that in which an independent voltage source is connected to the

reference node. The following example illustrates this case.

Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 3.11a. Let us determine all node voltages and branch currents.

This network has three nonreference nodes with labeled node voltages and Based

on our previous discussions, we would assume that in order to find all the node voltages we

would need to write a KCL equation at each of the nonreference nodes. The resulting three

linearly independent simultaneous equations would produce the unknown node voltages.

However, note that and are known quantities because an independent voltage source is

connected directly between the nonreference node and each of these nodes. Therefore,

and Furthermore, note that the current through the 9-kΩ resistor is

from left to right. We do not know or the current in the remain-

ing resistors. However, since only one node voltage is unknown, a single-node equation will

produce it. Applying KCL to this center node yields

V2

[12 - (-6)]兾9k = 2 mA

V3 = -6 V.

V1 = 12 V

V3

V1

V3.

V2,

V1, SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

3.5

irwin03_101-155hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:12 Page 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-137-320.jpg)

![114 C H A P T E R 3 N O D A L A N D L O O P A N A LY S I S T E C H N I Q U E S

or

from which we obtain

Once all the node voltages are known, Ohm’s law can be used to find the branch currents

shown in Fig. 3.11b. The diagram illustrates that KCL is satisfied at every node.

Note that the presence of the voltage sources in this example has simplified the analysis,

since two of the three linear independent equations are and We will

find that as a general rule, whenever voltage sources are present between nodes, the node

voltage equations that describe the network will be simpler.

V3 = -6 V.

V1 = 12 V

V2 =

3

2

V

V2 - 12

12k

+

V2

6k

+

V2 - (-6)

12k

= 0

V2 - V1

12k

+

V2 - 0

6k

+

V2 - V3

12k

= 0

-

+

±

–

±

–

V3

V1

V2

12 k⍀ 12 k⍀

9 k⍀

6 k⍀ 6 V

12 V

(a)

-

+

12 k⍀ 12 k⍀

9 k⍀

6 k⍀ 6 V

12 V

(b)

3

2

— V

2

k

— A

7

8k

— A

23

8k

— A

1

4k

— A

21

8k

— A

5

8k

— A

+12 V –6 V

Figure 3.11

Circuit used in

Example 3.5.

E3.7 Use nodal analysis to find the current in the network in Fig. E3.7.

Io

Learning Assessment

ANSWER: Io =

3

4

mA.

±

–

±

–

Vo

Io

6 k⍀ 6 k⍀

6 V 3 k⍀ 3 V

2 mA

6 k⍀

3 k⍀

6 k⍀

8 mA

12 V

1 k⍀

2 k⍀

Vo

+

–

±

–

Figure E3.7

Any time an independent

voltage source is connected

between the reference node

and a nonreference node,

the nonreference node volt-

age is known.

[ h i n t ]

E3.8 Find V0 in Fig. E3.8 using nodal analysis. ANSWER: V0 = 3.89 V.

Figure E3.8

irwin03_101-155hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:12 Page 114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-138-320.jpg)

![through is The directions of the currents have been assumed. As was the case in the

nodal analysis, if the actual currents are not in the direction indicated, the values calculated will

be negative.

Applying KVL to the first loop yields

KVL applied to loop 2 yields

where

Substituting these values into the two KVL equations produces the two simultaneous

equations required to determine the two loop currents; that is,

or in matrix form

At this point, it is important to define what is called a mesh. A mesh is a special kind of loop

that does not contain any loops within it. Therefore, as we traverse the path of a mesh, we do not

encircle any circuit elements. For example, the network in Fig. 3.19 contains two meshes defined

by the paths A-B-E-F-A and B-C-D-E-B. The path A-B-C-D-E-F-A is a loop, but it is not a mesh.

Since the majority of our analysis in this section will involve writing KVL equations for meshes,

we will refer to the currents as mesh currents and the analysis as a mesh analysis.

B

R1 + R2 + R3

-R3

-R3

R3 + R4 + R5

R B

i1

i2

R = B

vS1

-vS2

R

-i1AR3B + i2AR3 + R4 + R5B = -vS2

i1AR1 + R2 + R3B - i2AR3B = vS1

v1 = i1R1, v2 = i1R2, v3 = Ai1 - i2BR3, v4 = i2R4, and v5 = i2R5.

+vS2 + v4 + v5 - v3 = 0

+v1 + v3 + v2 - vS1 = 0

i1 - i2.

R3

S E C T I O N 3 . 2 L O O P A N A LY S I S 123

The equations employ the

passive sign convention.

[ h i n t ]

±

–

–

±

A B C

F E D

vS1

v1

v2

vS2

v5

v4

R4

v3

R3

R1

R2 R5

i1 i2

+

-

+

+

-

-

- + - +

Figure 3.19

A two-loop circuit.

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

3.12

Consider the network in Fig. 3.20a. We wish to find the current

We will begin the analysis by writing mesh equations. Note that there are no + and - signs

on the resistors. However, they are not needed, since we will apply Ohm’s law to each resis-

tive element as we write the KVL equations. The equation for the first mesh is

The KVL equation for the second mesh is

where

Solving the two simultaneous equations yields and Therefore,

All the voltages and currents in the network are shown in Fig. 3.20b. Recall

from nodal analysis that once the node voltages were determined, we could check our analy-

sis using KCL at the nodes. In this case, we know the branch currents and can use KVL around

any closed path to check our results. For example, applying KVL to the outer loop yields

0 = 0

-12 +

15

2

+

3

2

+ 3 = 0

Io = 3兾4 mA.

I2 = 1兾2 mA.

I1 = 5兾4 mA

Io = I1 - I2.

6kAI2 - I1B + 3kI2 + 3 = 0

-12 + 6kI1 + 6kAI1 - I2B = 0

Io.

irwin03_101-155hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:12 Page 123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-147-320.jpg)

![128 C H A P T E R 3 N O D A L A N D L O O P A N A LY S I S T E C H N I Q U E S

-

+

4 mA

2 mA 3 V

2 k⍀

4 k⍀

6 k⍀

4 k⍀

Vo

+

-

I3

I1

I2

Figure 3.23

Circuit used in

Example 3.15.

What we have demonstrated in the previous example is the general approach for dealing

with independent current sources when writing KVL equations; that is, use one loop through

each current source. The number of “window panes” in the network tells us how many equa-

tions we need. Additional KVL equations are written to cover the remaining circuit elements

in the network. The following example illustrates this approach.

Let us find in the network in Fig. 3.24a.

First, we select two loop currents and such that passes directly through the 2-mA

source, and passes directly through the 4-mA source, as shown in Fig. 3.24b. Therefore,

two of our three linearly independent equations are

The remaining loop current must pass through the circuit elements not covered by the two

previous equations and cannot, of course, pass through the current sources. The path for this

remaining loop current can be obtained by open-circuiting the current sources, as shown in

Fig. 3.24c. When all currents are labeled on the original circuit, the KVL equation for this

last loop, as shown in Fig. 3.24d, is

Solving the equations yields

and therefore,

Next consider the supermesh technique. In this case the three mesh currents are specified

as shown in Fig. 3.24e, and since the voltage across the 4-mA current source is unknown,

it is assumed to be The mesh currents constrained by the current sources are

The KVL equations for meshes 2 and 3, respectively, are

-6 + 1kI3 + V

x + 1kAI3 - I1B = 0

2kI2 + 2kAI2 - I1B - V

x = 0

I2 - I3 = 4 * 10-3

I1 = 2 * 10-3

Vx.

Io = I1 - I2 - I3 =

-4

3

mA

I3 =

-2

3

mA

-6 + 1kI3 + 2kAI2 + I3B + 2kAI3 + I2 - I1B + 1kAI3 - I1B = 0

I3

I2 = 4 * 10-3

I1 = 2 * 10-3

I2

I1

I2

I1

Io

SOLUTION

In this case the 4-mA current

source is located on the

boundary between two mesh-

es. Thus, we will demonstrate

two techniques for dealing

with this type of situtation.

One is a special loop tech-

nique, and the other is known

as the supermesh approach.

[ h i n t ]

EXAMPLE

3.16

irwin03_101-155hr.qxd 30-06-2010 13:12 Page 128](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-152-320.jpg)

![S U M M A R Y 179

facts imply that a new resistor value is needed and the output voltage should be shifted

down so that the minimum is zero. We begin by computing the necessary resistor value:

The resistor voltage will now range from to , or 1.25 to 6.25 V.

We must now design a circuit that shifts these voltage levels so that the range is 0 to 5 V.

One possible option for the level shifter circuit is the differential amplifier shown in

Fig. 4.30. Recall that the output voltage of this device is

Since we have already chosen R for a voltage span of 5 V, the gain of the amplifier should

be 1 (i.e., ). Clearly, the value of the required shift voltage is 1.25 V. However, we

can verify this value by inserting the minimum values into this last equation

and find

There is one caveat to this design. We don’t want the converter resistor, R, to affect

the differential amplifier, or vice versa. This means that the vast majority of the

4–20 mA current should flow entirely through R and not through the differential ampli-

fier resistors. If we choose and this requirement will be met. Therefore,

we might select so that their resistance values are more than 300

times that of R.

R1 = R2 = 100 k

R2 W R,

R1

V

shift = (312.5)(0.004) = 1.25 V

0 = [(312.5)(0.004) - V

shift]

R2

R1

R1 = R2

V

o = (V

I - V

shift)

R2

R1

(0.02)(312.5)

(0.004)(312.5)

R =

V

max - V

min

Imax - Imin

=

5 - 0

0.02 - 0.004

= 312.5

VI

Vshift

+

-

Vo

+

-

R2

R2

R1

R1

R

4–20 mA

Differential amplifier with shifter

±

–

–

±

Figure 4.30

A 4–20 mA to 0–5 V

converter circuit.

S U M M A R Y

■ Op-amps are characterized by

High-input resistance

Low-output resistance

Very high gain

■ The ideal op-amp is modeled using

■ Op-amp problems are typically analyzed by writing node

equations at the op-amp input terminals

■ The output of a comparator is dependent on the difference

in voltage at the input terminals

v+ = v-

i+ = i- = 0

•

irwin04-156-188hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:17 Page 179](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-203-320.jpg)

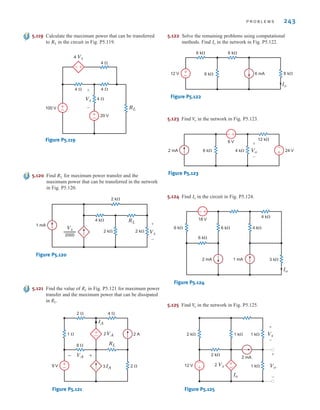

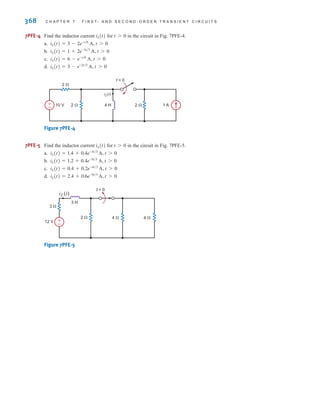

![6.1

Capacitors

A capacitor is a circuit element that consists of two conducting surfaces separated by a non-

conducting, or dielectric, material. A simplified capacitor and its electrical symbol are shown

in Fig. 6.1.

There are many different kinds of capacitors, and they are categorized by the type of

dielectric material used between the conducting plates. Although any good insulator can

serve as a dielectric, each type has characteristics that make it more suitable for particular

applications.

For general applications in electronic circuits (e.g., coupling between stages of amplifica-

tion), the dielectric material may be paper impregnated with oil or wax, mylar, polystyrene,

mica, glass, or ceramic.

Ceramic dielectric capacitors constructed of barium titanates have a large

capacitance-to-volume ratio because of their high dielectric constant. Mica, glass, and ceram-

ic dielectric capacitors will operate satisfactorily at high frequencies.

Aluminum electrolytic capacitors, which consist of a pair of aluminum plates separated

by a moistened borax paste electrolyte, can provide high values of capacitance in small vol-

umes. They are typically used for filtering, bypassing, and coupling, and in power supplies

and motor-starting applications. Tantalum electrolytic capacitors have lower losses and more

stable characteristics than those of aluminum electrolytic capacitors. Fig. 6.2 shows a variety

of typical discrete capacitors.

In addition to these capacitors, which we deliberately insert in a network for specific

applications, stray capacitance is present any time there is a difference in potential between

two conducting materials separated by a dielectric. Because this stray capacitance can cause

246 C H A P T E R 6 C A P A C I T A N C E A N D I N D U C T A N C E

Figure 6.2

Some typical capacitors.

(Courtesy of Mark Nelms and

Jo Ann Loden)

d

Dielectric

(a)

C

q(t)

v(t)

(b)

+

+

-

-

i=—

dq

dt

A

Figure 6.1

A capacitor and its

electrical symbol.

Note the use of the passive

sign convention.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 246](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-270-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 6 . 3 C A P A C I T O R A N D I N D U C T O R C O M B I N A T I O N S 265

Determine the equivalent capacitance and the initial voltage for the circuit shown in Fig. 6.14.

Note that these capacitors must have been charged before they were connected in series or

else the charge of each would be equal and the voltages would be in the same direction.

The equivalent capacitance is

where all capacitance values are in microfarads.

Therefore, CS=1 F and, as seen from the figure, Note that the total

energy stored in the circuit is

However, the energy recoverable at the terminals is

= 4.5 J

=

1

2

C1 * 10-6

(-3)2

D

wCAt0B =

1

2

CSv2

(t)

= 31 J

wAt0B =

1

2

C2 * 10-6

(2)2

+ 3 * 10-6

(-4)2

+ 6 * 10-6

(-1)2

D

vAt0B = -3 V.

1

CS

=

1

2

+

1

3

+

1

6

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

6.12

Therefore, Eq. (6.13) can be written as follows using Eq. (6.14):

6.15

6.16

where

and

6.17

Thus, the circuit in Fig. 6.13b is equivalent to that in Fig. 6.13a under the conditions stated

previously.

It is also important to note that since the same current flows in each of the series capaci-

tors, each capacitor gains the same charge in the same time period. The voltage across each

capacitor will depend on this charge and the capacitance of the element.

1

CS

= a

N

i=1

1

Ci

=

1

C1

+

1

C2

+ p +

1

CN

vAt0B = a

N

i=1

viAt0B

=

1

CS 3

t

t0

i(t)dt + vAt0B

v(t) = a a

N

i=1

1

Ci

b

3

t

t0

i(t)dt + a

N

i=1

viAt0B

4 V

3 F

2 F

6 F

v(t)

+

+

-

-

2 V

+ -

1 V

+ -

Figure 6.14

Circuit containing multiple

capacitors with initial

voltages.

Capacitors in series combine

like resistors in parallel.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 265](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-289-320.jpg)

![266 C H A P T E R 6 C A P A C I T A N C E A N D I N D U C T A N C E

Two previously uncharged capacitors are connected in series and then charged with a 12-V

source. One capacitor is 30 F and the other is unknown. If the voltage across the 30-F

capacitor is 8 V, find the capacitance of the unknown capacitor.

The charge on the 30-F capacitor is

Q=CV=(30 F)(8 V)=240 C

Since the same current flows in each of the series capacitors, each capacitor gains the same

charge in the same time period:

C =

Q

V

=

240 C

4V

= 60 F

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

6.13

PARALLEL CAPACITORS To determine the equivalent capacitance of N capacitors

connected in parallel, we employ KCL. As can be seen from Fig. 6.15a,

6.18

6.19

where

Cp=C1+C2+C3+p+CN 6.20

= Cp

dv(t)

dt

= a a

N

i=1

Ci b

dv(t)

dt

= C1

dv(t)

dt

+ C2

dv(t)

dt

+ C3

dv(t)

dt

+ p + CN

dv(t)

dt

i(t) = i1(t) + i2(t) + i3(t) + p + iN(t)

v(t)

+

-

i1(t)

i(t)

v(t)

+

-

i(t)

C1 C2 C3 CN

i2(t) i3(t) iN(t)

(a) (b)

Cp

Figure 6.15

Equivalent circuit for

N capacitors connected

in parallel.

Determine the equivalent capacitance at terminals A-B of the circuit shown in Fig. 6.16.

Cp = 15 F

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

6.14

v(t)

+

-

A

B

4 F 6 F 2 F 3 F

Figure 6.16

Circuit containing

multiple capacitors

in parallel.

Capacitors in parallel combine

like resistors in series.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-290-320.jpg)

![268 C H A P T E R 6 C A P A C I T A N C E A N D I N D U C T A N C E

where

6.24

Therefore, under this condition the network in Fig. 6.17b is equivalent to that in Fig. 6.17a.

LS = a

N

i=1

Li = L1 + L2 + p + LN

v(t)

L1

LN

L2 L3

+

+

-

-

i(t) v1(t)

- +

vN(t)

+ -

v2(t) + -

v3(t)

v(t) LS

+

-

i(t)

(a) (b)

Figure 6.17

Equivalent circuit

for N series-connected

inductors.

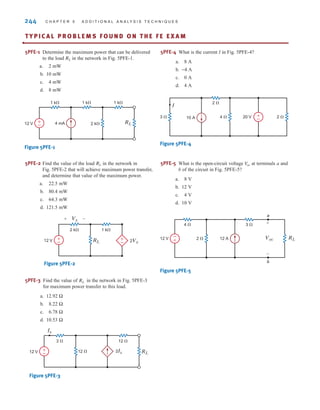

Find the equivalent inductance of the circuit shown in Fig. 6.18.

The equivalent inductance of the circuit shown in Fig. 6.18 is

LS=1H+2H+4H

=7H

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

6.15

v(t) 4 H

1 H 2 H

+

-

Figure 6.18

Circuit containing

multiple inductors.

PARALLEL INDUCTORS Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 6.19a, which contains N

parallel inductors. Using KCL, we can write

i(t)=i1(t)+i2(t)+i3(t)+p+iN(t) 6.25

However,

6.26

Substituting this expression into Eq. (6.25) yields

6.27

6.28

=

1

Lp 3

t

t0

v(x)dx + iAt0B

i(t) = a a

N

j=1

1

Lj

b

3

t

t0

v(x)dx + a

N

j=1

ijAt0B

ij(t) =

1

Lj 3

t

t0

v(x)dx + ijAt0B

Inductors in series combine

like resistors in series.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 268](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-292-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 6 . 3 C A P A C I T O R A N D I N D U C T O R C O M B I N A T I O N S 269

Determine the equivalent inductance and the initial current for the circuit shown in

Fig. 6.20.

The equivalent inductance is

where all inductance values are in millihenrys:

Lp=2 mH

and the initial current is iAt0B = -1 A.

1

Lp

=

1

12

+

1

6

+

1

4

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

6.16

where

6.29

and is equal to the current in Lp at t=t0. Thus, the circuit in Fig. 6.19b is equivalent to

that in Fig. 6.19a under the conditions stated previously.

iAt0B

1

Lp

=

1

L1

+

1

L2

+

1

L3

+ p +

1

LN

v(t)

+

-

i1(t)

i(t)

L1

i2(t)

L2

i3(t) iN(t)

L3 LN

v(t)

+

-

i(t)

Lp

(a) (b)

Figure 6.19

Equivalent circuits for

N inductors connected

in parallel.

v(t)

+

-

3 A

i(t)

12 mH

6 A

6 mH

2 A

4 mH

Figure 6.20

Circuit containing

multiple inductors with

initial currents.

The previous material indicates that capacitors combine like conductances, whereas

inductances combine like resistances.

E6.14 Determine the equivalent inductance of the network in Fig. E6.14 if all inductors

are 6 mH.

Learning Assessment

ANSWER: 9.429 mH.

Leq

Figure E6.14

Inductors in parallel combine

like resistors in parallel.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 269](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-293-320.jpg)

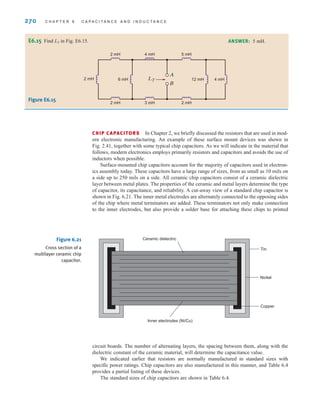

![272 C H A P T E R 6 C A P A C I T A N C E A N D I N D U C T A N C E

6.4

RC Operational

Amplifier Circuits

Two very important RC op-amp circuits are the differentiator and the integrator. These cir-

cuits are derived from the circuit for an inverting op-amp by replacing the resistors R1 and

R2, respectively, by a capacitor. Consider, for example, the circuit shown in Fig. 6.25a. The

circuit equations are

However, v–=0 and i–=0. Therefore,

6.30

vo(t) = -R2C1

dv1(t)

dt

C1

d

dt

Av1 - v-B +

vo - v-

R2

= i-

v–

±

–

R2

C1

v1(t)

v– i–

v± i±

vo

+

-

(a)

±

–

C2

R1

v1(t)

i–

v± i±

vo

+

-

(b)

-

+

-

+

Figure 6.25

Differentiator and integrator

operational amplifier circuits.

Thus, the output of the op-amp circuit is proportional to the derivative of the input.

The circuit equations for the op-amp configuration in Fig. 6.25b are

but since v–=0 and i–=0, the equation reduces to

or

6.31

If the capacitor is initially discharged, then vo(0)=0; hence,

6.32

Thus, the output voltage of the op-amp circuit is proportional to the integral of the input

voltage.

vo(t) =

-1

R1C2 3

t

0

v1(x)dx

=

-1

R1C2 3

t

0

v1(x)dx + vo(0)

vo(t) =

-1

R1C2 3

t

-q

v1(x)dx

v1

R1

= -C2

dvo

dt

v1 - v-

R1

+ C2

d

dt

Avo - v-B = i-

The properties of the ideal

op-amp are v⫹ ⫽ v⫺ and

i⫹ ⫽ i⫺ ⫽ 0.

[ h i n t ]

irwin06-245-295hr.qxd 9-07-2010 14:27 Page 272](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-296-320.jpg)

![we might call a free-body diagram of the right half of the network in Fig. 7.1a, as shown

in Fig. 7.1c (that is, a charged capacitor that is discharged through a resistor). When the

switch is closed, KCL for the circuit is

or

In the next section we will demonstrate that the solution of this equation is

Note that this function is a decaying exponential and the rate at which it decays is a function

of the values of R and C. The product RC is a very important parameter, and we will give it

a special name in the following discussions.

vC(t) = V

o e-t兾RC

dvC(t)

dt

+

1

RC

vC(t) = 0

C

dvC(t)

dt

+

vC(t)

R

= 0

298 C H A P T E R 7 F I R S T- A N D S E C O N D - O R D E R T R A N S I E N T C I R C U I T S

Discharge

time

Charge

time

Vo

(b)

vC(t)

t

RS

R

[(R) Xenon lamp]

VS

C

(a)

vC(t)

+

-

(c)

vC(t) R

C

+

-

Figure 7.1

Diagrams used to

describe a camera’s

flash circuit.

7.2

First-Order

Circuits

GENERAL FORM OF THE RESPONSE EQUATIONS In our study of first-order tran-

sient circuits we will show that the solution of these circuits (i.e., finding a voltage or cur-

rent) requires us to solve a first-order differential equation of the form

7.1

Although a number of techniques may be used for solving an equation of this type, we will

obtain a general solution that we will then employ in two different approaches to transient

analysis.

A fundamental theorem of differential equations states that if is any solution

to Eq. (7.1), and is any solution to the homogeneous equation

7.2

dx(t)

dt

+ ax(t) = 0

x(t) = xc(t)

x(t) = xp(t)

dx(t)

dt

+ ax(t) = f(t)

irwin07_296-368hr.qxd 28-07-2010 11:34 Page 298](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-322-320.jpg)

![The Step-by-Step Approach In the previous analysis technique, we derived the differ-

ential equation for the capacitor voltage or inductor current, solved the differential equation,

and used the solution to find the unknown variable in the network. In the very methodical

technique that we will now describe, we will use the fact that Eq. (7.11) is the form of the

solution and we will employ circuit analysis to determine the constants and .

From Eq. (7.11) we note that as t S q, and Therefore, if the circuit

is solved for the variable x(t) in steady state (i.e., t S q) with the capacitor replaced by an

open circuit [v is constant and therefore ] or the inductor replaced by a

short circuit [i is constant and therefore ], then the variable

Note that since the capacitor or inductor has been removed, the circuit is a dc circuit with

constant sources and resistors, and therefore only dc analysis is required in the steady-state

solution.

The constant in Eq. (7.11) can also be obtained via the solution of a dc circuit in which

a capacitor is replaced by a voltage source or an inductor is replaced by a current source. The

value of the voltage source for the capacitor or the current source for the inductor is a known

value at one instant of time. In general, we will use the initial condition value since it is gen-

erally the one known, but the value at any instant could be used. This value can be obtained

in numerous ways and is often specified as input data in a statement of the problem. However,

a more likely situation is one in which a switch is thrown in the circuit and the initial value

of the capacitor voltage or inductor current is determined from the previous circuit (i.e., the

circuit before the switch is thrown). It is normally assumed that the previous circuit has

reached steady state, and therefore the voltage across the capacitor or the current through the

inductor can be found in exactly the same manner as was used to find

Finally, the value of the time constant can be found by determining the Thévenin equiva-

lent resistance at the terminals of the storage element. Then for an RC circuit, and

for an RL circuit.

Let us now reiterate this procedure in a step-by-step fashion.

= L兾RTh

= RThC

K1.

K2

x(t) = K1.

v = L(di兾dt) = 0

i = C(dv兾dt) = 0

x(t) = K1.

e-at

S 0

K1, K2,

306 C H A P T E R 7 F I R S T- A N D S E C O N D - O R D E R T R A N S I E N T C I R C U I T S

Step 1. We assume a solution for the variable x(t) of the form

Step 2. Assuming that the original circuit has reached steady state before a switch was

thrown (thereby producing a new circuit), draw this previous circuit with the

capacitor replaced by an open circuit or the inductor replaced by a short circuit.

Solve for the voltage across the capacitor, or the current through the

inductor, prior to switch action.

Step 3. Recall from Chapter 6 that voltage across a capacitor and the current flowing

through an inductor cannot change in zero time. Draw the circuit valid for

with the switches in their new positions. Replace a capacitor with a

voltage source or an inductor with a current source of value

Solve for the initial value of the variable

Step 4. Assuming that steady state has been reached after the switches are thrown,

draw the equivalent circuit, valid for by replacing the capacitor by

an open circuit or the inductor by a short circuit. Solve for the steady-state

value of the variable

Step 5. Since the time constant for all voltages and currents in the circuit will be the

same, it can be obtained by reducing the entire circuit to a simple series circuit

containing a voltage source, resistor, and a storage element (i.e., capacitor or

inductor) by forming a simple Thévenin equivalent circuit at the terminals of

x(t)|t75 ⬟ x(q)

t 7 5,

x(0+).

iL(0+) = iL(0-).

vC(0+) = vC(0-)

t = 0+

iL(0-),

vC(0-),

x(t) = K1 + K2e-t兾

.

Problem-Solving Strategy

Using the Step-by-

Step Approach

irwin07_296-368hr.qxd 28-07-2010 11:34 Page 306](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-330-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 7 . 2 F I R S T- O R D E R C I R C U I T S 307

the storage element. This Thévenin equivalent circuit is obtained by looking

into the circuit from the terminals of the storage element. The time constant for

a circuit containing a capacitor is and for a circuit containing an

inductor it is

Step 6. Using the results of steps 3, 4, and 5, we can evaluate the constants in step 1 as

Therefore, and hence the solution is

Keep in mind that this solution form applies only to a first-order circuit having

dc sources. If the sources are not dc, the forced response will be different.

Generally, the forced response is of the same form as the forcing functions

(sources) and their derivatives.

x(t) = x(q) + [x(0+) - x(q)]e-t兾

K1 = x(q), K2 = x(0+) - x(q),

x(q) = K1

x(0+) = K1 + K2

= L兾RTh.

= RTh C,

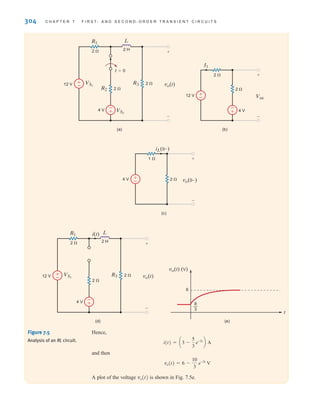

Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 7.6a. The circuit is in steady state prior to time t=0,

when the switch is closed. Let us calculate the current i(t) for

Step 1. i(t) is of the form

Step 2. The initial voltage across the capacitor is calculated from Fig. 7.6b as

Step 3. The new circuit, valid only for is shown in Fig. 7.6c. The value of the

voltage source that replaces the capacitor is Hence,

Step 4. The equivalent circuit, valid for is shown in Fig. 7.6d. The current i(q)

caused by the 36-V source is

Step 5. The Thévenin equivalent resistance, obtained by looking into the open-circuit

terminals of the capacitor in Fig. 7.6e, is

Therefore, the circuit time constant is

= 0.15 s

= a

3

2

b A103

B(100)A10-6

B

= RThC

RTh =

(2k)(6k)

2k + 6k

=

3

2

k⍀

=

9

2

mA

i(q) =

36

2k + 6k

t 7 5,

=

16

3

mA

i(0+) =

32

6k

vC(0-) = vC(0+) = 32 V.

t = 0+,

= 32 V

vC(0-) = 36 - (2)(2)

K1 + K2e-t兾

.

t 7 0.

SOLUTION

EXAMPLE

7.3

irwin07_296-368hr.qxd 28-07-2010 11:34 Page 307](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-331-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 7 . 5 D E S I G N E X A M P L E S 349

iL(t), we should reduce s1. Hence, let us choose s1=1. Since s1+s2 must equal 20,

s2=19. Under these conditions

and

Thus, the current is

which is shown in Fig. 7.51b. At 100 ms the current is 2.52 A. Also, at t=1.1 s, the cur-

rent is 1.11 A—above the 1-A requirement. Therefore, the choice of C=263 mF meets all

starter specifications.

iL(t) = 3.33Ce-t

- e-19t

D A

K1 =

60

s2 - s1

=

60

18

= 3.33

C =

1

Ls1s2

=

1

(0.2)(1)(19)

= 263 mF

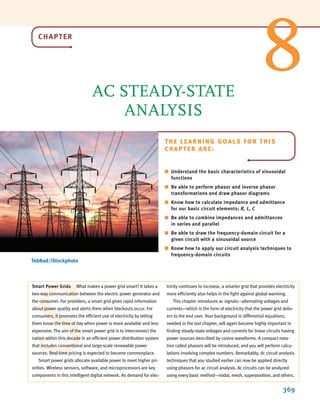

A defibrillator is a device that is used to stop heart fibrillations—erratic uncoordinated

quivering of the heart muscle fibers—by delivering an electric shock to the heart. The Lown

defibrillator was developed by Dr. Bernard Lown in 1962. Its key feature, shown in Fig. 7.52a,

is its voltage waveform. A simplified circuit diagram that is capable of producing the Lown

waveform is shown in Fig. 7.52b. Let us find the necessary values for the inductor and

capacitor.

DESIGN

EXAMPLE 7.21

SOLUTION

(b)

3000

0 5 10

Time (milliseconds)

vo(t) (V)

(a)

vo(t)

VS

6000 V

R=50

patient

C

i(t)

L

t=0

+

-

Figure 7.52 Lown defibrillator waveform and simplified circuit. Reprinted with permission from John

Wiley Sons, Inc., Introduction to Biomedical Equipment Technology.

Since the Lown waveform is oscillatory in nature, we know that the circuit is underdamped

and the voltage applied to the patient is of the form

where

and

o =

1

1LC

= o 21 - 2

o =

R

2L

vo(t) = K1e-ot

sin[t]

( 6 1)

•

irwin07_296-368hr.qxd 28-07-2010 11:34 Page 349](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-373-320.jpg)

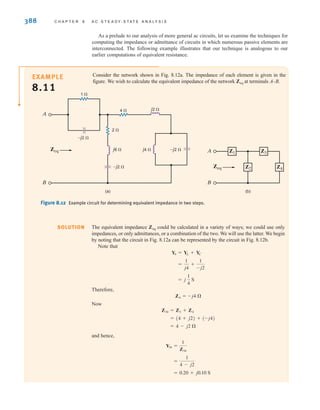

![8.1

Sinusoids

Let us begin our discussion of sinusoidal functions by considering the sine wave

8.1

where x(t) could represent either v(t) or i(t). XM is the amplitude, maximum value, or peak

value; is the radian or angular frequency; and t is the argument of the sine function. A

plot of the function in Eq. (8.1) as a function of its argument is shown in Fig. 8.1a. Obviously,

the function repeats itself every 2 radians. This condition is described mathematically as

, or in general for period T, as

8.2

meaning that the function has the same value at time t+T as it does at time t.

xC(t + T)D = x(t)

x(t + 2) = x(t)

x(t) = XM sint

370 C H A P T E R 8 A C S T E A D Y- S T A T E A N A LY S I S

The waveform can also be plotted as a function of time, as shown in Fig. 8.1b. Note that

this function goes through one period every T seconds. In other words, in 1 second it goes

through 1/T periods or cycles. The number of cycles per second, called Hertz, is the

frequency f, where

8.3

Now since as shown in Fig. 8.1a, we find that

8.4

which is, of course, the general relationship among period in seconds, frequency in Hertz,

and radian frequency.

Now that we have discussed some of the basic properties of a sine wave, let us consider

the following general expression for a sinusoidal function:

8.5

In this case is the argument of the sine function, and is called the phase angle.

A plot of this function is shown in Fig. 8.2, together with the original function in Eq. (8.1)

for comparison. Because of the presence of the phase angle, any point on the waveform

occurs radians earlier in time than the corresponding point on the wave-

form Therefore, we say that lags by radians. In the

more general situation, if

and

x2(t) = XM2

sin(t + )

x1(t) = XM1

sin(t + )

XM sin(t + )

XM sin t

XM sin t.

XM sin(t + )

(t + )

x(t) = XM sin(t + )

=

2

T

= 2f

T = 2,

f =

1

T

–XM

XM

–XM

XM

x(t)

—

2

——

2

3

2 t

(a)

x(t)

T

——

4

——

4

3T

T t

(b)

T

—

2

Figure 8.1

Plots of a sine wave as a

function of both and t.

t

The relationship between

frequency and period

[ h i n t ]

The relationship between

frequency, period, and radian

frequency

[ h i n t ]

Phase lag defined

[ h i n t ]

In phase and out of phase

defined

[ h i n t ]

irwin08_369-434hr.qxd 28-07-2010 12:03 Page 370](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-irwin-220801002926-2b111212/85/basic-engineering-circuit-analysis-10th-Irwin-pdf-394-320.jpg)

![S E C T I O N 8 . 1 S I N U S O I D S 371

then leads by - radians and lags by - radians. If =, the

waveforms are identical and the functions are said to be in phase. If the functions are

out of phase.

The phase angle is normally expressed in degrees rather than radians. Therefore, at this

point we will simply state that we will use the two forms interchangeably; that is,

8.6

Rigorously speaking, since t is in radians, the phase angle should be as well. However, it is

common practice and convenient to use degrees for phase; therefore, that will be our practice

in this text.

In addition, it should be noted that adding to the argument integer multiples of either 2

radians or 360° does not change the original function. This can easily be shown mathemati-

cally but is visibly evident when examining the waveform, as shown in Fig. 8.2.

Although our discussion has centered on the sine function, we could just as easily have

used the cosine function, since the two waveforms differ only by a phase angle; that is,

8.7

8.8