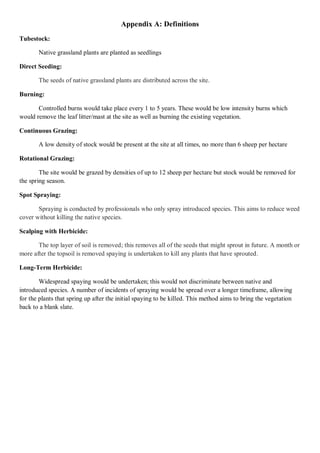

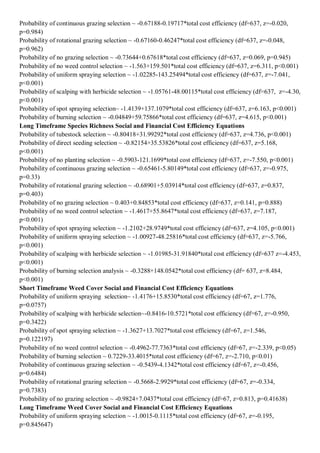

The document discusses a project aimed at developing a framework for managing grassland biodiversity in the critically endangered temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plains, where key objectives include integrating financial costs and community support into land management decisions. A Bayesian state-and-transition model is introduced to predict outcomes based on various management actions, highlighting that burning every three to five years is the preferred long-term strategy. The results emphasize the importance of stakeholder input in management decisions and provide insights into effective restoration practices while considering biodiversity impacts.