The document outlines guidelines for constructing persuasive arguments in a professional context, emphasizing the importance of understanding and respecting the audience's viewpoint while gathering evidence and forming judgments. It provides an assignment requiring a 2- to 3-paragraph essay on a controversial topic, integrating at least two of the eleven guidelines for effective persuasion. The guidelines stress approaches such as beginning from a point of commonality, taking a positive approach, and allowing time for the audience to accept one's perspective.

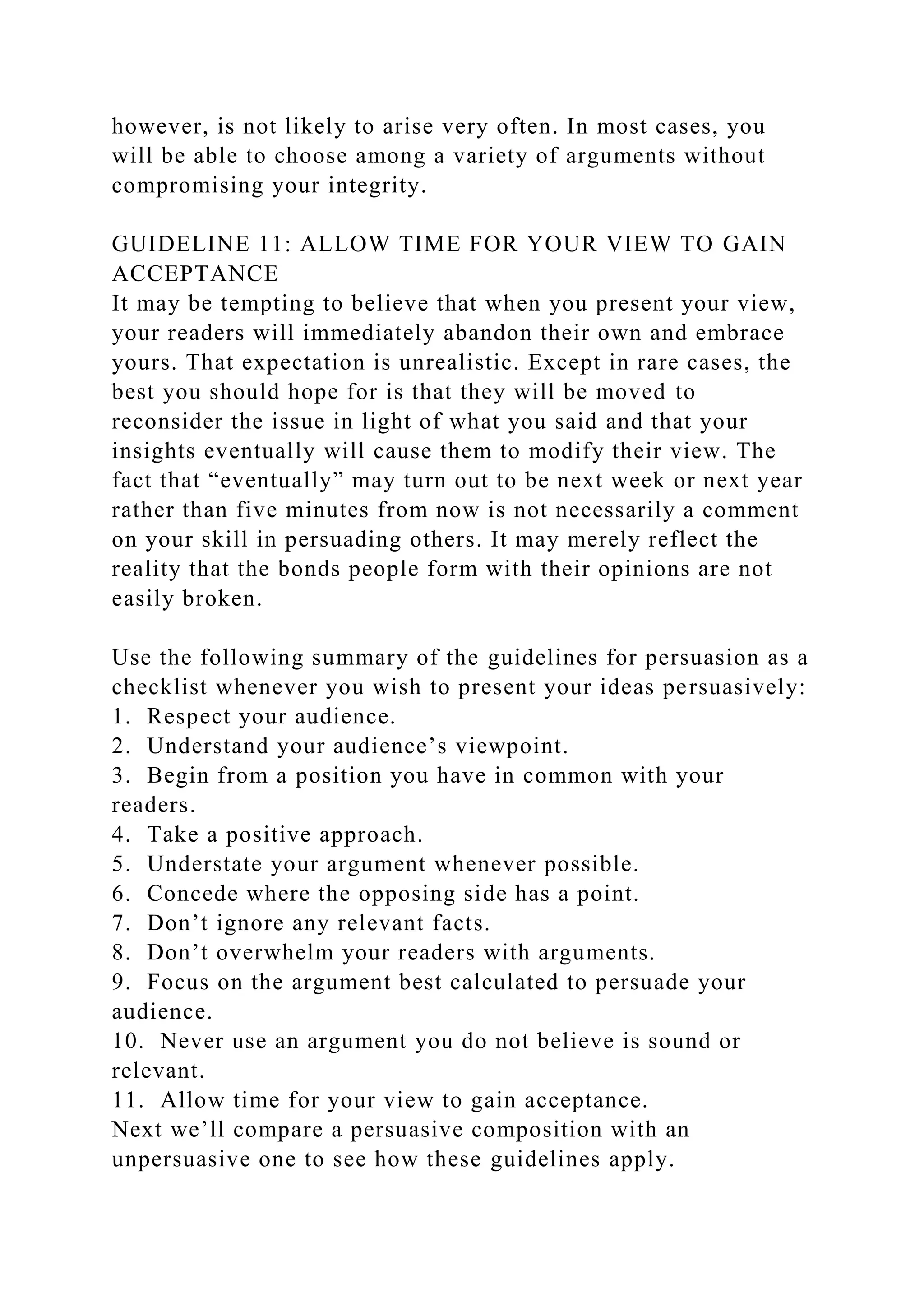

![Ruggiero, V. (02/2011). Beyond Feelings: A Guide to Critical

Thinking, 9th Edition. [VitalSource Bookshelf Online].

Retrieved from

https://digitalbookshelf.argosy.edu/#/books/1260050939/

Assignment 3: Persuasion Versus Judgment

Consider various guidelines for approaching controversial

topics, gathering evidence, forming judgments, and constructing

arguments to persuade others to agree with our judgments.

For this short assignment:

Think about the processes of forming a judgment and

persuading others in your professional environment. Construct a

2- to 3-paragraph essay intended to persuade someone to agree

with your position on a particular topic. Be sure to identify the

topic and cite and explain the evidence you consider supportive

of your position.

Make reference to the 11 guidelines for constructing persuasive

arguments, and apply two to three of them in your response.

You must cite the source of information you use. Apply current

APA standards for editorial style, expression of ideas, and

format of text, citations, and references.

Assignment 3 Grading Criteria

Maximum Points

Clearly and concisely identified a topic and explained a

position.

12

Accurately applied at least two guidelines for constructing

arguments in your response.

48

Offered and explained supporting evidence.

20

Applied current APA standards for editorial style, expression of

ideas, and format of text, citations, and references.

Professionally presented the position by using good grammar,

spelling, and punctuation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3persuasionversusjudgmentconsidervariousguideli-221026114623-7b400f72/75/Assignment-3-Persuasion-Versus-JudgmentConsider-various-guideli-docx-6-2048.jpg)