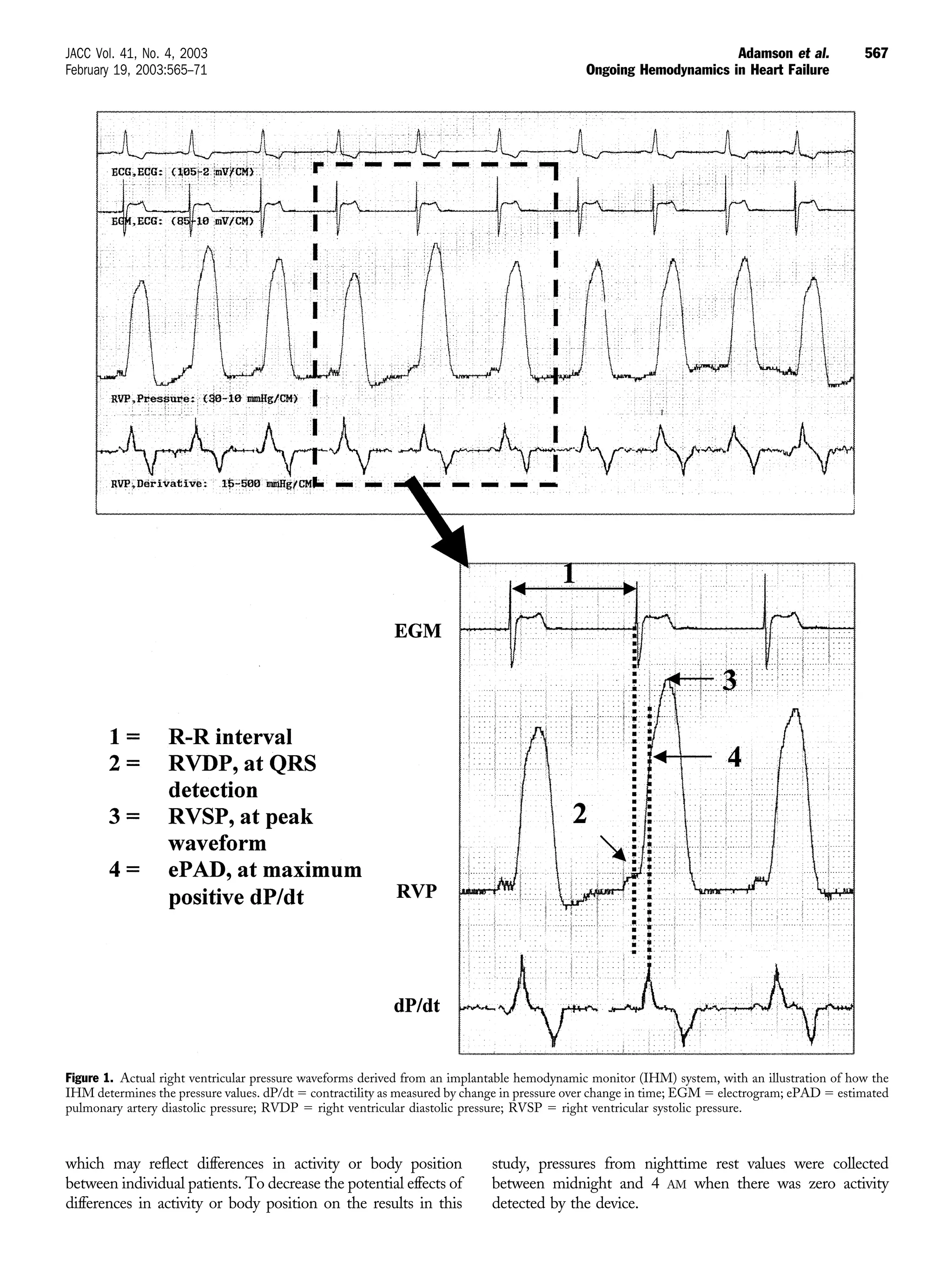

This study examined data from an implantable hemodynamic monitor in 32 heart failure patients over 9 months without using the data for management, and then over 17 months where the data was incorporated into management. The study found that right ventricular pressures increased before volume overload events requiring hospitalization. After using the hemodynamic data for management, hospitalizations decreased by 57% compared to the previous year. Long-term hemodynamic monitoring may help guide heart failure management and reduce hospitalizations.