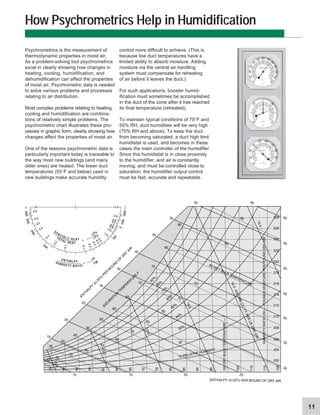

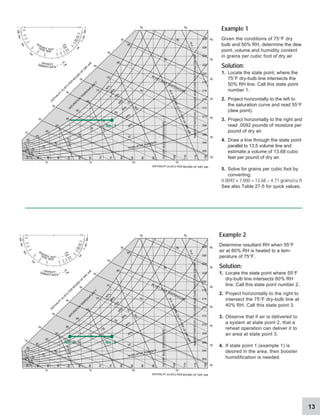

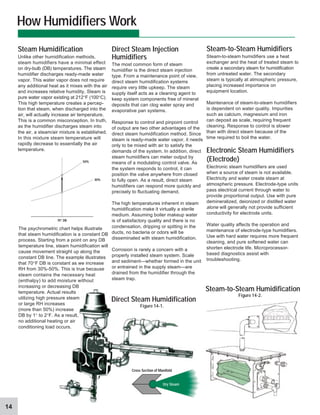

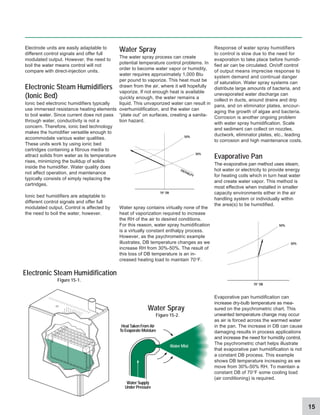

This document discusses the importance of humidity control and humidification. Maintaining proper humidity levels indoors is important for human comfort, equipment performance, and material preservation. Improper humidity can damage materials and equipment or cause discomfort. The document outlines key humidity concepts like relative humidity and dew point. It explains how humidification can enhance indoor environments while also saving energy by reducing moisture absorption from other sources.