This document discusses antimicrobial resistance and provides information on several key points:

- It defines antimicrobial resistance and explains why it is a global concern due to the rise of hard-to-treat infections.

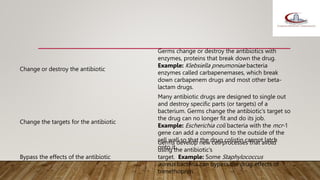

- It outlines the current situation of drug resistance in several pathogens like E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, HIV, malaria, and fungi. Mechanisms of resistance include restricting antibiotic access, destroying antibiotics, and changing antibiotic targets.

- Factors contributing to resistance include inappropriate antibiotic use in humans, animals, and the environment.

- Actions to address resistance include preventing infections, improving antibiotic use, and halting resistance spread.

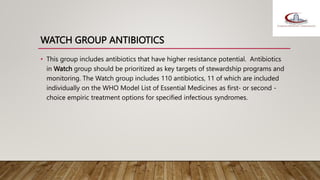

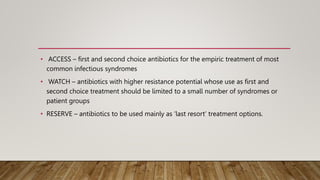

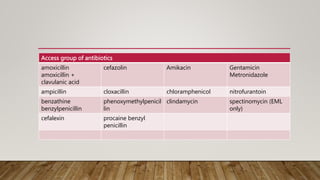

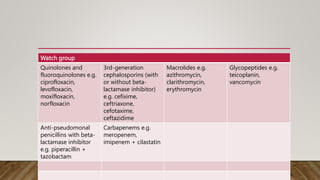

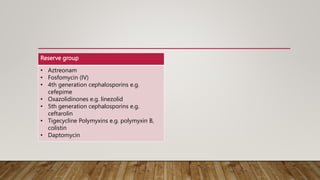

- The WHO AWaRe classification system categorizes antibiotics based