The document provides an overview of the endocrine system, specifically focusing on the anatomy and functions of the pituitary gland and thyroid gland. It details the structure and hormone production of both the anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary gland, as well as the mechanisms of hormone release and their roles in the body. Additionally, the document explains the synthesis and functions of thyroid hormones, including the processes involved in iodide absorption and hormone secretion.

![Hormones of the Anterior Lobe

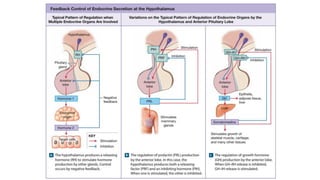

The functions and control mechanisms of seven hormones from the anterior lobe are reasonably well understood.

1. Thyroid-stimulating hormone;

2. Adrenocorticotropic hormone;

3. Two gonadotropins called follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone;

4. Prolactin;

5. Growth hormone; and

6. Melanocyte stimulating hormone.

Of the six hormones produced by the pars distalis, four regulate the production of hormones by other endocrine

glands. The names of these hormones indicate their activities.

The hormones of the anterior lobe are also called tropic hormones (trope, a turning). They “turn on” endocrine

glands or support the functions of other organs. (Some sources call them trophic hormones [trophe, nourishment]

instead.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anatomyglands2022-2023-240428105902-0d882d91/85/Anatomy-Glands-First-Proff-2022-2023-pdf-11-320.jpg)