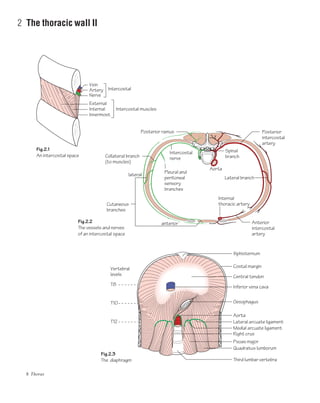

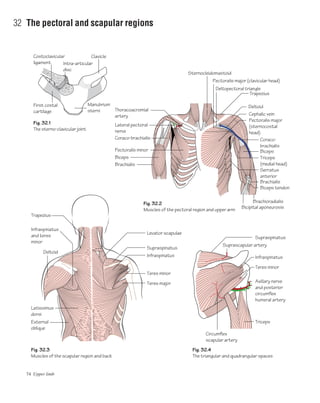

1. The thoracic wall is formed by the sternum, vertebral column, ribs, and intercostal spaces. It contains muscles like the external and internal intercostals in each intercostal space.

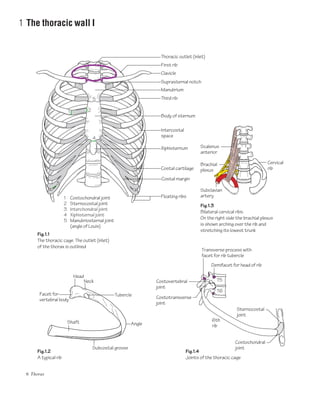

2. Each typical rib has a head, tubercle, and shaft. The first rib is unique with a single facet and prominent scalene tubercle. The floating 11th and 12th ribs do not reach the sternum.

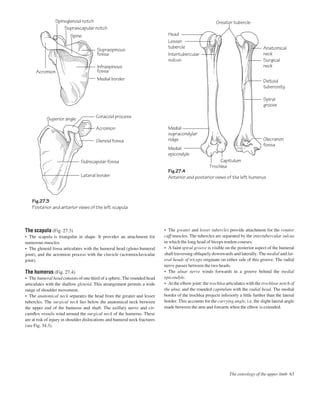

3. The sternum comprises the manubrium, body, and xiphoid process. Costal cartilages connect the first seven ribs to the sternum. The thoracic cage has various joint types including sternocostal and costoverte

![© 2002 by Blackwell Science Ltd

a Blackwell Publishing company

Editorial Offices:

Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0EL, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1865 206206

Blackwell Science, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5018, USA

Tel: +1 781 388 8250

Blackwell Science Asia Pty, 54 University Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300

Blackwell Wissenschafts Verlag, Kurfürstendamm 57, 10707 Berlin, Germany

Tel: +49 (0)30 32 79 060

The right of the Authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior

permission of the publisher.

First published 2002 by Blackwell Science Ltd

Reprinted 2002

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Faiz, Omar.

Anatomy at a glance / Omar Faiz, David Moffat

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-632-05934-6 (pbk.)

1. Human anatomy—Outlines, syllabi, etc. I. Moffat, David, MD. II. Title.

[DNLM: 1: Anatomy. QS 4 F175a 2002]

QM31 .F33 2002

611—dc21 2001052646

ISBN 0-632-05934-6

A Catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Set in 9/11A pt Times by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

Printed and bound in Italy by G. Canale & C. SpA, Turin

For further information on

Blackwell Science, visit our website:

www.blackwell-science.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anatomyataglance-140812110216-phpapp01/85/Anatomy-ata-glance-3-320.jpg)