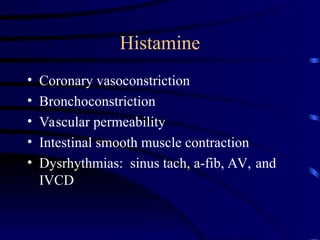

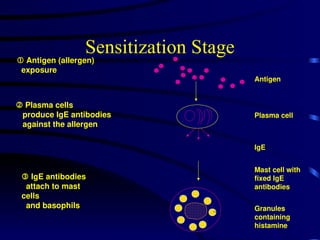

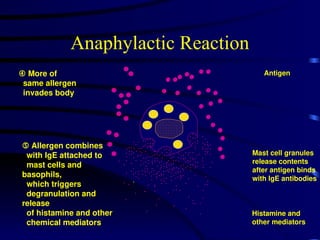

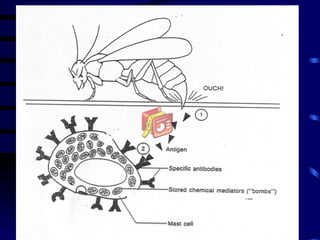

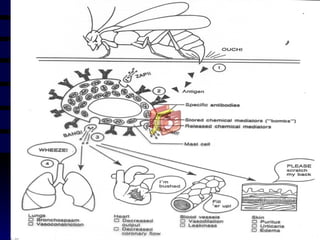

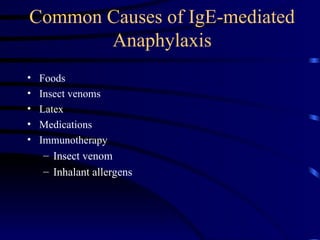

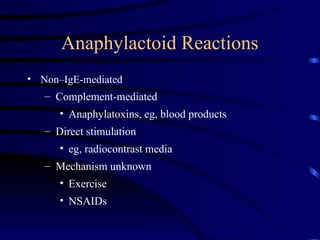

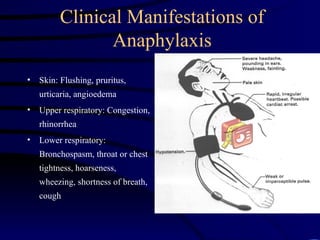

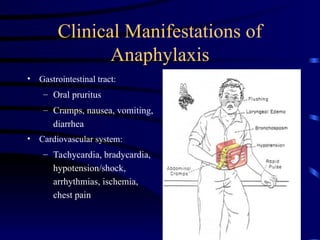

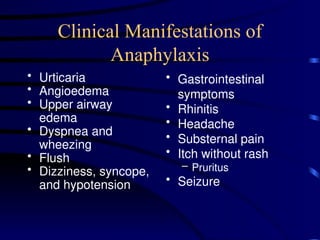

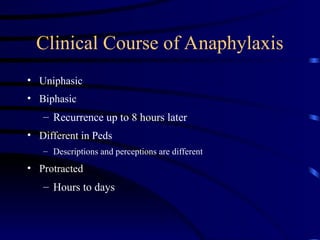

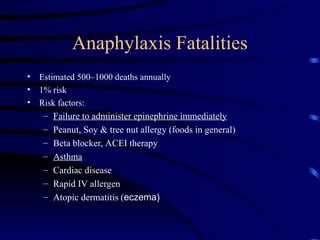

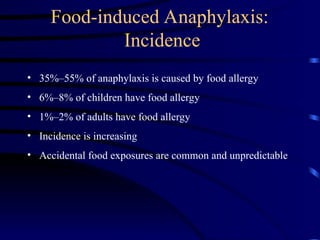

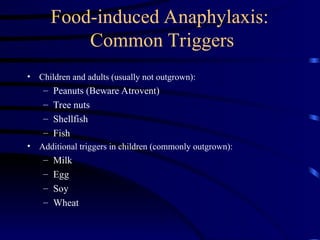

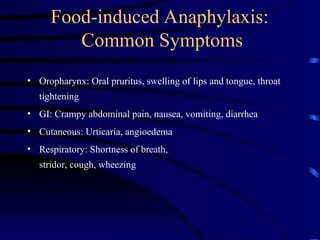

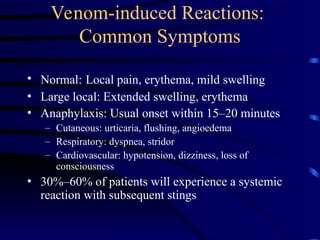

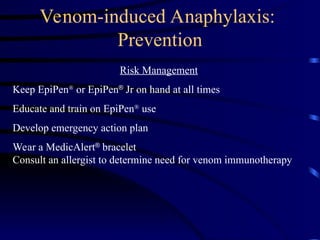

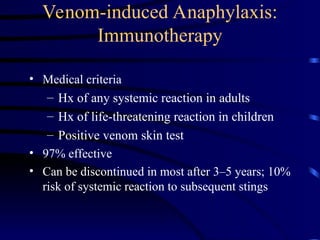

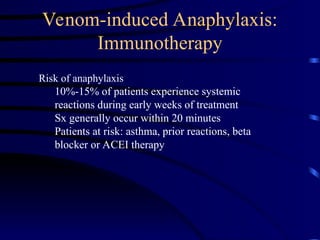

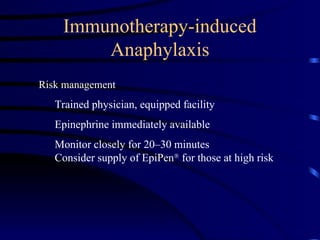

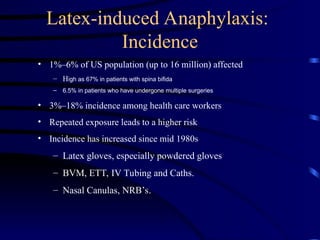

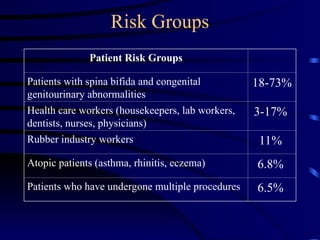

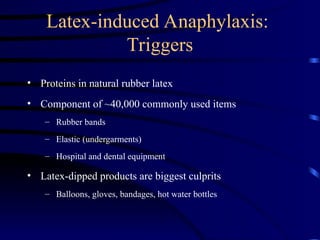

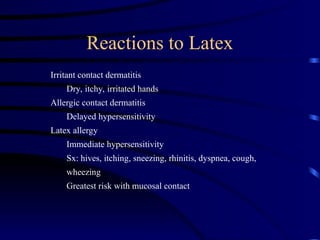

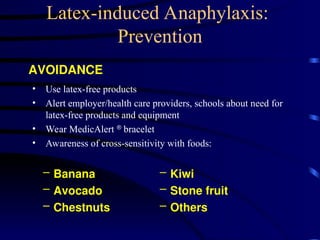

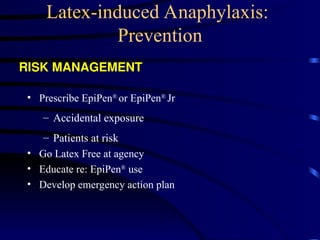

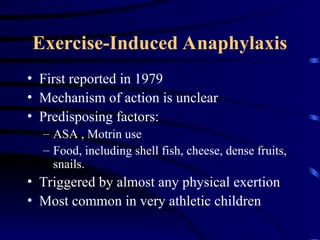

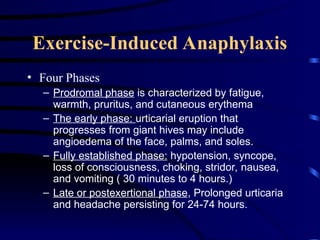

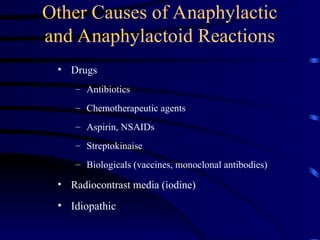

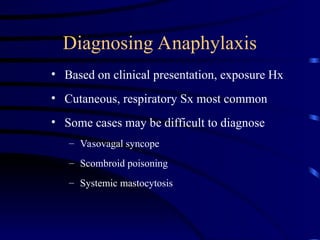

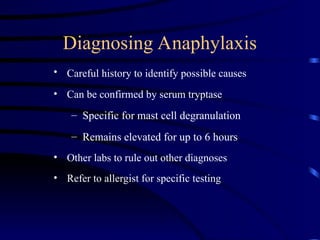

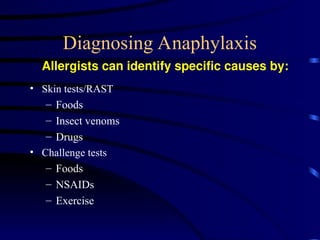

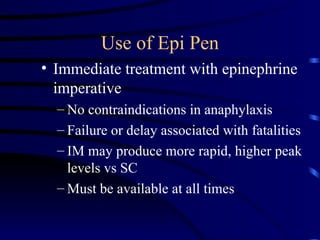

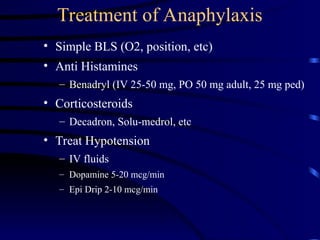

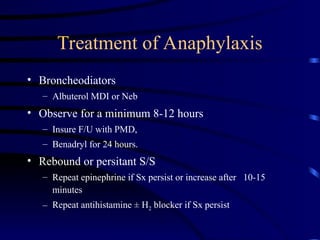

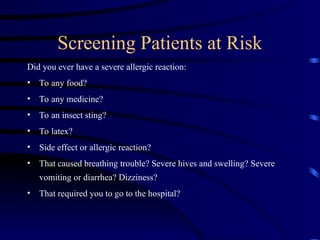

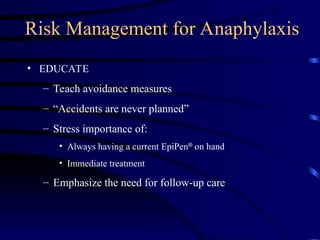

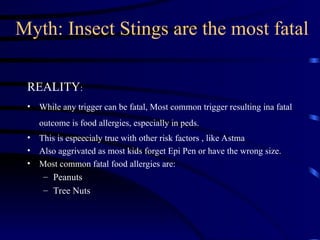

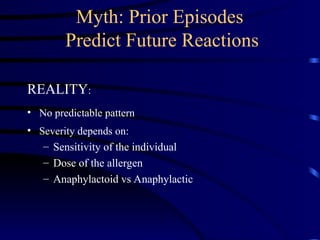

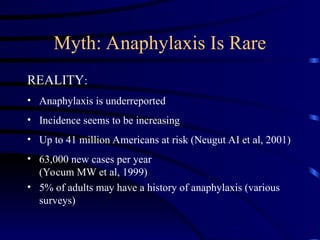

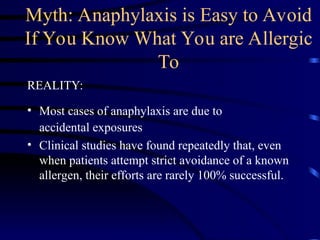

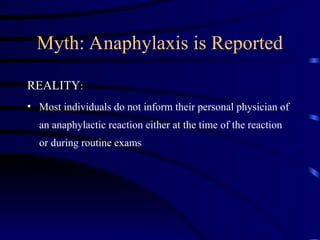

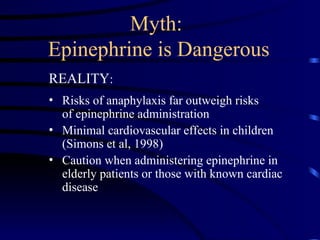

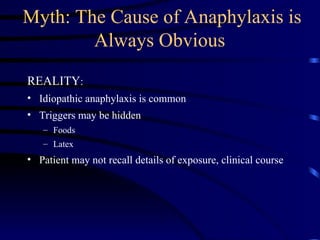

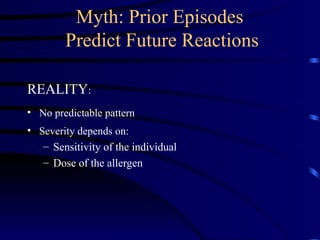

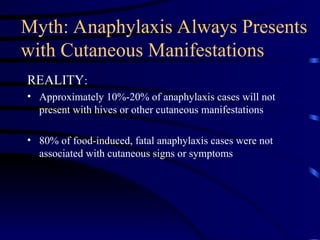

The document provides a comprehensive overview of anaphylaxis, including its definition, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and risk factors. It highlights the importance of recognizing triggers such as food, insect venoms, and latex, along with the necessity of immediate epinephrine treatment. Preventive measures, including education and immunotherapy, are also discussed as critical strategies for managing anaphylaxis risks.