This document presents a framework for analyzing group processes more systematically. It discusses past research that has focused on either cognitive or socio-emotional aspects of groups using coarse analyses. The proposed new framework combines these aspects and organizes individual actions along five dimensions: evaluation, knowledge, validity, invitation, and politeness. These dimensions help measure how well a group works together over time. The framework and a new statistical method called multilevel Logit with time series analyses can help address issues like changing effects over time in modeling group processes.

![Analyzing Group Work Processes:… 3

view. By coordinating these views, they can resolve their conflict to construct deeper

understanding (Piaget's [1952] equilibration). Consider two children, Ana and Sean.

They agree that two tall glasses have the same amount of grape juice. Ana pours all the

juice from one glass into a short, wide bowl. She then says that the wider bowl has more

juice. Sean disagrees. He argues that the taller glass has more. By pointing out the

height and width differences to one another, they can help each other understand that

these differences offset one another. Eventually, they recognize that each container has

the same amount of juice. Through cognitive conflict, Ana and Sean develop a new idea.

Groups can also distribute their cognitive processing among its members for both

efficiency and error reduction. Wegner (1987) showed that groups rely on subsets of

members to remember information related to their area of expertise, "transactive

memory." This distributed memory allows group members to use their limited memory

efficiently. Likewise, the multiple perspectives of different group members allow the

group as a whole to recognize errors more easily (Vygotsky 1997).

Socio-emotional Aspect of Group Processes

Group work promotes friendship and emotional support even among very different

people. Group work provides opportunities to work together for common goals, to get to

know one another and work as equals (Allport, 1954). Group work also creates

conditions conducive for making friends: contact, perceived similarity, and engagement

in pleasant activities (Lott & Lott, 1965). When facing daunting obstacles, members can

provide emotional support for one another to continue working.

However, group processes are not always smooth. Salomon & Globerson (1989)

showed that members may loaf, resentfully withdraw (in response to other's loafing) or

dominate group interactions. Members may also be overly aggressive/hostile (Dodge,

Asher & Parkhurst, 1989) or passive/acquiescent (Chiu, 1997b).

In addition to unproductive individual behaviors, some group processes can also

hinder effective group work. For example, group members often do not reveal important

information and fail to evaluate alternatives appropriately.

Difficulties with providing information

Group members often do not share valuable information due to unequal opportunities

to participate and concern over harm to their public self-image, or face.

Groups rarely discuss their discussion procedures to ensure equitable participation

rates (Hackman & Morris, 1975). So, each group's talk often showed a speaker hierarchy

(Bales, 1953; Stephan & Mishler, 1952). The most frequent speaker often talked much

more often than the second most frequent speaker. This difference between adjacent

ranks becomes decreasingly smaller at lower ranks (Bales, 1953; Stephan & Mishler,

1952). Differences in members' status (Fisek, Berger & Norman, 1991), perception of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-3-320.jpg)

![Analyzing Group Work Processes:… 5

Difficulties with coordinating different views

If group members reveal all their information, the groups often choose the optimal

solution (if there is one –"truth wins" [Laughlin, 1999]). However, they do not always do

so. Correct member can have difficulty persuading others of the correct solution. Or,

groups can use inappropriate methods for choosing among alternatives.

Laughlin and Hollingshead (1995) identified 4 conditions for demonstrating a correct

idea. They are (a) group consensus on a conceptual system, (b) sufficient information, (c)

other members' ability to recognize a correct idea and (d) sufficient correct member

ability, motivation and time to persuade other members that the answer is correct.

Laughlin and Ellis (1986) further argued that the number of group members necessary

and sufficient for a collective decision is inversely proportional to the demonstrability of

the proposed solution. One person is enough on eureka/insight problems (Shaw, 1932),

remote verbal associations and most math problems. Two people ("truth-supported")

suffice on world knowledge such as vocabulary, analogies and general information

(Hastie, 1986). However, a majority or more are needed for choice dilemmas, evaluative

attitudinal judgments, preferences for bets/gambles and mock jury decisions.

Faced with several alternative, groups do not always try to determine the correct one.

Laughlin and Hollingshead (1995) also identified three alternatives for resolving conflicts

in addition to "create new alternative," "truth wins," and "truth-supported wins." They are

voting, turn-taking and random selection among alternatives. As a majority vote can be

the final arbitrator, group members may strategically adapt their talk. They tend to

support majority positions and avoid support for minority positions (Kerr & Watts, 1982).

The influence of the majority depends on several factors. These include majority and

minority sizes, the extremity of the majority position, the minority response mode

(private vs. public) and the type of decision (see review by Levine & Thompson, 1996).

CLASSIFICATION SCHEMES FOR GROUP PROCESSES

Past researchers focusing on group members' behaviors have classified them in

several ways. These include discussion phases, individual roles and strategies. Earlier

researchers used classification systems based on discussion phases (Bales & Strodtbeck,

1951; Hirokawa, 1983). Examples of phases include (a) discuss problem, (b) discuss

criteria, (c) propose solutions and (d) evaluate proposals. However, groups do not

proceed through phases in a regular manner (Hirokawa, 1983; Poole, 1981). Other

researchers have used role classifications (E. Cohen, 1994b; Kagan, 1992). Roles

include proposer, supporter, critic and facilitator. Other researchers focus on specific

strategies (Barnes & Todd, 1977; Cazden, 1988; Forman & Cazden, 1984; Slavin, 1990).

Examples of strategies include proposing new ideas, justifying, identifying weaknesses,

inviting participation, etc. During each discussion phase, group members play different

roles and use particular strategies. During the proposal phase, a proposer suggests new

ideas. During the evaluation phase, supporters and critics evaluate it, seeking advantages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-5-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

8

others. It ranges from face-promoting to neutral to face-threatening. Face-promoting

(☺) actions improve the public self-image of others, "yes, two times six is right, giving us

twelve," (a face-promoting disagreement). So, group members may use face-promoting

actions to show respect, build friendship and minimize interpersonal conflicts. In

contrast, face-threatening ( ) actions are impolite, "can't you even multiply two and six

correctly to get twelve?" Unless the speakers are close friends, face-threatening acts

signal psychological rejection of the person. So, listeners are tempted to reciprocate. If

they do, a spiral of face-threatening actions can tear the social fabric and end the

collaboration. Lastly, face-neutral ( ) actions do not strongly affect others' faces, "two

hours times six miles per hour is twelve miles."

Several factors affect the level of politeness used. These factors include relative

power, social distance and degree of imposition (Brown & Levinson, 1987). A speaker

typically addresses a more powerful listener politely; for example, secretaries usually

speak politely to their bosses. So, speaker's level of politeness may reflect the existing

status hierarchy or help create it during a status struggle (Bales, 1951). In the absence of

a clear status hierarchy, speakers may use impolite behavior to stake a claim to higher

status. Also, socially distant people, such as strangers, tend to speak in polite formalities.

In contrast, close friends are less likely to be so polite (Schiffrin, 1984). They may even

use face-threatening acts playfully (e.g., ritualistic insults [Goodwin, 1990]). Lastly,

speakers often use polite language when imposing on the listener in some way, for

example, asking for a favor.

Knowledge

The knowledge content dimension characterizes the problem knowledge displayed

during the interaction and includes at least three possibilities: contribution, repetition, and

null content. Contributions (C) are new problem solving ideas or actions introduced into

the collaboration. They can be wrong and hence indicate moments of potential problem

solving progress. Contributions include new goals, proposals, justifications,

consequences, critiques, alternatives, etc. Tracing the contributions provides a map of the

group's problem solving route. Meanwhile, repetitions (R) repeat the knowledge content

of previous actions, not necessarily the immediately preceding action (Schegloff, 1996).

Repetitions can indicate the speaker's level of understanding and degree of agreement.

Finally, null content actions (N) do not include any problem content. They include

acknowledgments ("mm-hmm"), simple evaluations ("no"), and general questions

("what?"). Because null actions are often brief, they can serve as back channel actions

that provide feedback without interrupting the current speaker. (Null actions can be

repeated, but they remain null actions, as repetitions repeat problem solving information.)

The continuum of problem knowledge content runs through non-overlapping

contributions, overlapping contributions, synonymous repetitions, partial repetitions,

exact repetitions, and null actions. Consider each type of knowledge content in response

to the phrase "two hours times six miles per hour." A non-overlapping contribution

provides problem information without repeating any part of any previous action, for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-8-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

10

short, definitive summaries, definitive goals, uncertain summaries, and uncertain goals

are all statements, but invite increasing audience participation.

Rhetorical, tag, choice, open, and directive questions (?) also invite different degrees

of interaction. Although the form of a rhetorical question invites responses ("can't you do

anything right?"), the speaker knows the answer and does not expect a response. Tag

questions follow statements and anticipate simple acknowledgments, "two times six is

twelve, right?" Meanwhile, choice questions offer multiple possibilities from which the

audience can select, "should we add or multiply?" When speakers ask open questions,

they do not restrict the answers and invite a greater variety of responses, "what should we

do next?" Finally, directive questions expect audience implementation of a proposal, "can

you compute the speed?" Rhetorical, tag, choice, open, and directive questions invite

successively greater degrees of interaction.

Finally, people can invite different degrees of participation using open, closed or halt

commands (!). Open commands request general input from the audience, "give me your

opinion," whereas closed commands specify particular actions, "measure the length of the

box." Although most commands demand audience action, halt commands demand

audience inaction, for example, “wait!" As a result, halt commands are less invitational

than statements as they discourage participation. Halt commands disagree (-) and have

null knowledge content (N) that distinguish them from other commands (!). So, they can

be analyzed as a separate unit (-N!). Open and detailed commands demand audience

participation, but halt commands demand audience inaction.

Collaborators invite audience participation in increasing degrees from halt commands

to statements to questions to non-halt commands.

Interactive Properties of Individual Actions

The evaluation, politeness, knowledge content, and invitational form dimensions

capture interactive properties. Because evaluations look backward into the past at the

previous utterance, they help glue together individual actions to form a coherent

conversation. Collaborations in which participants are highly responsive toward one

another have more evaluations (supportive [+] or critical[-]). Meanwhile, speakers often

reciprocate politeness levels to reflect their social relationships. While contributions help

trace the group's problem solving paths, repetitions of other speakers display areas of

perceived-shared understanding (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). The invitational form

dimension mirrors the evaluation dimension and projects forward into the future by

inviting audience participation to different degrees. Together, evaluations, politeness

levels, repetitions and invitational forms link adjacent actions to help create coherent

interactions and allow quantitative tests of collaboration quality.

2.4 Relating roles, strategies and individual actions

This classification captures the simultaneous multiple effects of an individual action

that theoretical constructs such as roles and strategies can not. To explicate the

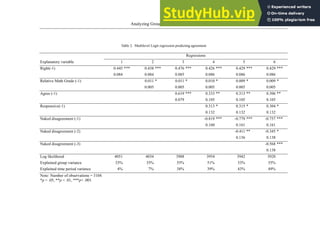

relationship between individual actions, roles and strategies (see Table 1), recall my](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-10-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

12

individual and turn levels. At the group level, he estimated the effects of the group's

actions (along with status and other variables) on solution score. In particular, he showed

that average mathematics grade, face promoting criticisms (-☺, % of total criticisms) and

correct actions (%) predicted solution score. However, contributions (%) and repetitions

(%) did not.

At the individual level, Chiu (2000) estimated predictors of perceived leadership. He

showed that social status positively predicted perceived leadership. Meanwhile, the

individual ratio of face-promoting to total criticisms negatively predicted it. However,

correct actions (%), contributions (%), and repetitions (%) did not.

Lastly, he tested evaluation distortions using lagged variables to predict agreement (at

time T) of the previous speaker turn (at time T-1). He found that the previous turn's

correctness (at T-1) predicted agreement (at T). However, the previous speaker's

mathematical grade (at T-1) and social status (at T-1) both positively distorted the

evaluation. This turn level analysis had several shortcomings addressed by the new

methodology described below

A NEW STATISTICAL METHOD: DYNAMIC MULTILEVEL LOGIT

This section outlines a statistical method that addresses the problems that often occur

during analyses of group processes (see Chiu & Khoo [2000] for details). This method

combines multilevel analysis, a discrete outcome variable (Logit), break point estimation

and time-series analysis.

Difficulties During Analyses of Group Processes

Statistical models of group processes at the speaker turn/utterance level are

problematic in at least six ways.

1) Coding difficulties reduce both inter-coder reliability and the precision of

parameter estimates.

2) Data is often collected from different groups (group heterogeneity). So, each

group can show different effects (Goodman, Ravlin & Schminke, 1987).

3) Group members' behaviors at the beginning of a problem solving session can

differ from those at the end, a.k.a. time period heterogeneity (Dabbs & Ruback,

1987). Thus, each time period can show different effects (Goodman et al., 1987).

4) Deciding how to divide each session into different time periods is difficult. The

number and locations of "break points" in a session must be estimated.

5) The outcome variables (e.g., correctness, agreement) are often discrete rather

than continuous.

6) Time series data is often serially correlated − variables depend on values from

earlier turns. If not modeled properly, serial correlation in the errors can bias the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-12-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

14

Multi-dimensional coding

A coding scheme with many dimensions can capture the data's complexity. At the

same time, it can avoid sharp falls in inter-coder reliability and parameter estimate

precision. In the above framework, there are up to 243 actions (35

, 5 dimensions, each

with 3 categories). By coding one dimension at a time, a coder chooses among only 3

possible codes (instead of 243). Thus, training and coding time is shorter. Likewise,

inter-coder reliability likely improves.

Parameter estimates will likely be more precise as well. Instead of 242 binary

variables (243 - 1), only 10 binary variables are needed (3 - 1 or 2 per dimension,

2 × 5 = 10). Thus, the model will have fewer degrees of freedom. Moreover, specific

rare behaviors are now combinations of variable values. So, they are less likely to cause

multi-collinearity problems. As a result, this model with fewer explanatory variables and

likely less multi-collinearity probably has more precise parameter estimates.

In short, using multiple dimensions retains the categories’ complexity, helps check

for mutually exclusive codes, likely improves inter-coder reliability and improves the

precision of parameter estimates.

Multilevel Analysis

Multilevel analysis techniques (Goldstein, 1995) address group-specific and time

period-specific effects (heterogeneity). (This method is also called hierarchical linear

modeling or HLM [Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992]). A multilevel model estimates the

relationship between an outcome variable and sets of explanatory variables defined at

different units of analysis (or levels). For example, a person's turn of talk occurs within a

specific time period within a particular group. These different levels (turn of talk, time

period, group) are nested in a hierarchical structure.

Logit and Multilevel Models

We often use binary outcome variables to estimate the probability of observing or not

observing an event. For example, in our models of group processes we can estimate the

likelihood of agreeing with the previous speaker or not. The standard method for

modeling binary outcome variables is to use Logit models (see Greene [1997] for a

discussion of multinomial and ordered regressions)

Estimating Break Points to Identify Different Time Periods

Group processes occur over time. So, group process data are time series data. As](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-14-320.jpg)

![Analyzing Group Work Processes:… 17

Analysis

The analysis proceeded in the following order. First, we identified the time periods

and break points using the method outlined in Maddala & Kim (1998). Second, we tested

for heterogeneity across groups and across time periods with a variance components

model. Third, the multilevel Logit models were estimated using the software MLn.

Fourth, we tested for residual serial correlation with Q-statistics. (A lagged outcome

variable, agree[-1] was sufficient to eliminate the serial correlation.) Fifth, we estimated

the effect sizes for each explanatory variable with sequential (or hierarchical) regressions

(see J. Cohen & P. Cohen, 1983). Lastly, we tested for direct and indirect effects using

path analysis (see J. Cohen & P. Cohen, 1983).

Identify the different time periods. Conditions change over time. So, a model's

parameters might differ according to the time period. People might agree more often at

the end of a problem solving session than at the beginning of one. They might disagree

regularly until they find a correct method (a "break point" in the session). Afterwards,

they are likely to agree more often. So, for each group's data, we estimate the number

and locations of break points that divide the outcome variable AGREE into distinct time

periods.

Maddala & Kim (1998) outlines a method for identifying the number and locations of

break points in a time series. First, we identify an appropriate time series model for the

variable AGREE. Introducing explanatory variables into the model this early might raise

the difficulty of rejecting the null hyphothesis of no break points –even if they exist in the

full model (type II error). So, we used a time series model without any explanatory

variables to identify break points.

We identified the appropriate autoregressive model to use by minimizing the BIC.

This was done for all the groups. We found that most groups can best described by an

AR(1) model.

Yt = C + Yt-1 + ε

Next, we identified the break points. We assumed a maximum number of 5 break

points (or 6 time periods). (Assuming more would have been too computationally

intensive. Testing for an additional break point exponentially increases the computation

time.) We calculated the BIC for all possible locations of those break points in the time

series. This was done for all possible numbers of break points (0-5). The number and

locations of break points that minimized the BIC was chosen as the best estimate.

Heterogeneity of groups or time periods? Next, we used a variance components test

to check if the outcome variable, AGREE, significantly varied across groups or time

periods. If it does for both, both groups and time periods are heterogeneous. Then, a 3-

level model would be needed. In this 3-level model, speaker turns (level 1) are nested

within time periods (level 2) which are nested within each group (level 3).

Estimate model. We used multilevel Logit regressions to estimate a general time

series model. These regressions were run using the software MLn. The model included](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-17-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

18

all explanatory variables and lagged variables up to order 4. If groups or time periods are

heterogeneous, explanatory variable effects on agreement can vary across groups or

across time periods. So, we estimated the variations of the explanatory variables’ effects

across groups and across time periods. We included significant group and time period

variations in the model.

Next, we tested the significance of the explanatory variables, both as sets and

individually. We removed the non-significant ones. For binary outcome variables, the

likelihood ratio test is not reliable. So, we used Wald tests instead (Goldstein, 1995).

Non-significant variables were removed in the following order: higher order lagged turn

variables first (-4, then -3, then -2, then -1), then speaker variables. This yielded the final

model.

Serial correlation of residuals? We used Ljung-Box (1979) Q-statistics to test for

serial correlation (up to order 4) in the residuals for all 20 groups. If the residuals are not

serially correlated, then the model is likely an adequate time-series model. Also, the

estimates would likely be unbiased.

Effect sizes. We estimated the effect sizes of each explanatory variable in the final

model with sequential, multilevel Logit regressions. Recent events are more likely than

earlier events to affect agreement in the current turn. So, we entered the explanatory

variables in reverse temporal order into the sequential, multilevel Logit regressions.

Direct and indirect effects. Lastly, we tested for direct and indirect explanatory

variable effects with a path analysis. Temporal order constrains causal relationships, so

the final model's explanatory variables were entered in temporal order into the path

analysis.

All results were significant at the .05 level.

Results and Discussion

Overall, 72% of the on-task turns were correct. Evaluations included 54%

agreements, 0.3% neutral, 16% ignore/unresponsive turns, 18% polite disagreements and

9% rude disagreements (Cohen's kappa = .93, z = 49.5, p < .001).

Identify different time periods

The estimation of break points yielded 1 to 4 breakpoints for each group. This

resulted in 2 to 5 time periods for each group.

Heterogeneity of groups or time periods?

The variance components model showed significant variation of AGREE at both the

group level (0.14 [standard error = 0.05]) and the time period level (0.06 [0.02]). So, the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-18-320.jpg)

![Ming Ming Chiu

22

Figure 1. Multilevel Logit path analysis of predictors of agreement with the previous speaker

Limitations

This individual action framework does not capture fine gradations within each

category and omits the influence of many factors. For example, a simple addition such

“two plus one is three" and a novel representation that frames the solution to a problem

can both be contributions, but their impacts on the collaboration differ. This framework

omits the influence of many micro-level factors (such as prosody, rhythm and silence).

Adding micro-level elements can provide additional information for researchers to

improve their interpretation of interactional data. (See Auer & di Luzio [1992] and

Gumperz [1978] for discussions of prosody and rhythm and Schegloff [1995] for ways to

analyze silence.)

This macro-level factors (such as relationship histories, physical environments, and

societal/cultural expectations). Also, the shared history between people who know each

other provides common knowledge and psychological expectations that strangers lack.

Thus, a person may interpret and respond to a friend's action differently than to an

identical action by a stranger (Goodwin, 1990; Schiffrin, 1984). The physical

.01*

-

.56**

-.46***

.01*

-.57***

.31**

Math Status (-1)

Rudely

disagree (-3)

Rudely

disagree (-2)

Ignore (-1)

Rudely

disagree (-1)

Agree (-1)

Agree (0)

-.30*

-.76***

-.35*

-.01*

1.12***

.43***

Correct (-1)

1.12***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/analyzinggroupworkprocessestowardsaconceptualframeworkandsystematicstatisticalanalyses-230805182109-f48fbb83/85/Analyzing-Group-Work-Processes-Towards-A-Conceptual-Framework-And-Systematic-Statistical-Analyses-22-320.jpg)