1) This article describes a simple method for preliminary aircraft design requiring only paper, pencil, and a basic calculator. The example aircraft fits the proposed Light-Sport category carrying two people and 3 hours of fuel.

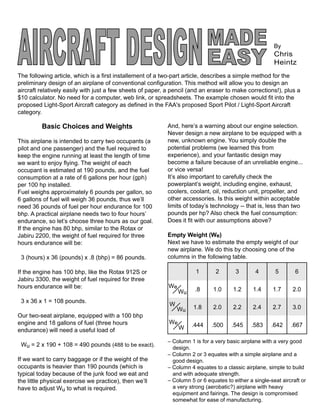

2) Basic choices are made including a 100hp engine, useful load of 510lbs, and an empty weight using a design table column. This results in a maximum weight of 1,224lbs.

3) Wing area is calculated to meet stall speed requirements of 45mph with flaps and 50mph clean. Performance values like top speed and rate of climb are then estimated.

![Yes, this is a wide range of aircraft options! Let us Without going into complicated theories (and then

not overestimate our design capability, especially if finding out that practically built wings may have lift

this is our first attempt at designing an airplane. coefficients quite different than from the theory) we

Unless we are geniuses, most likely our airplane will make a reasonably good estimate with the following

end up heavier than anticipated. So, let’s be humble configuration of wing sections with full-span flaps:

when determining the maximum weight:

W = We + Wu = Wu 1 + [ We

Wu ] CLmax = 1.4

Choosing to be a modest designer, we pick column CLEAN WING

4 as our guide to obtain our maximum weight:

W = 490 (1 + 1.4) = 1,176 pounds

CLmax = 2.2

This allows us an error of 1,232 pounds (the PLAIN FLAP

proposed weight for a Light-Sport Aircraft) minus

1,176 pounds, leaving us 56 pounds of “room for

error,” that is, being heavier than planned.

CLmax = 2.8

We could increase the useful load by 20 pounds to SLOTTED FLAP

510 pounds:

Wu = 490 + 20 = 510 pounds

CLmax = 3.6

LEADING EDGE SLAT

Then, AND SLOTTED FLAP

W = 510 (1 + 1.4) = 1,224 pounds maximum weight

Chord

That’s pretty close to the proposed 1,232 pounds

for a Light-Sport Aircraft. For a simple design, we choose a simple, plain

flap, and we do not forget that the flap portion of

Landing Speeds and Wing Area the wing is only about one-half of the wingspan

Having selected the weights, we now have to select (the ailerons occupy the outboard one-half span

the maximum stall speeds. The proposed Light- approximately).

Sport Aircraft category prescribes these as:

CLflaps down = 1/2 CLno flaps + 1/2 CLwith flaps

VSO = 39 knots = 45 mph (flaps down)

VS = 44 knots = 50 mph (clean configuration) = [1.4/2] + [2.2/2] = .7 + 1.1 = 1.8

and

At these speeds, the airplane will be easy and

relatively safe to land, which is one of the purposes CLclean = 1.4

of creating the Light-Sport Aircraft category.

If you are interested in designing an experimental With these values we find the required wing area (ρ)

category aircraft that exceeds the performance to meet the selected stall speed requirements:

parameters of a Light-Sport Aircraft.. .and you are a

good pilot.. .you could go up to a VSO of 60 mph. W = ρ x q x CLmax

But, be aware that above this speed, the energy ρv2 v2 v2

where q = 2 = 19.77 = 391

generated becomes so large that there is very little

chance of survival in the case of a landing accident. (q is in PSF, pounds per square foot, when V is in mph)

Next, we have to know the airplane’s maximum lift ρ= W

coefficient (CL) for both configurations -- flaps down

Or qCLmax and for

and flaps up (clean). The lift coefficient will depend 2

q = 50 = 6.4 psf

on the wing planform, Reynolds number, airfoil V= 50 mph 391

roughness, and center of gravity (CG) position.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aircraftdesign1-120225093605-phpapp01/85/Aircraft-design-1-2-320.jpg)