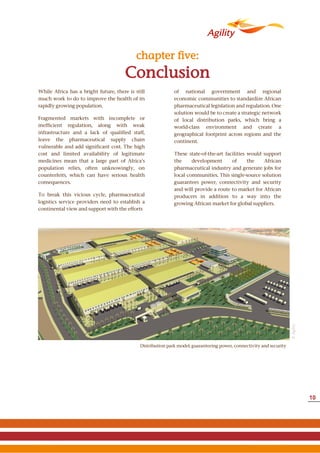

The document discusses the challenges and opportunities in Africa's pharmaceutical supply chain, emphasizing the need for improved visibility, infrastructure, and regulation to ensure secure and timely delivery of medicines. It highlights the high demand for pharmaceuticals due to changing demographics and disease burdens, alongside issues such as counterfeiting and inadequate healthcare workforce. A proposed model includes creating a strategic network of distribution parks to enhance logistics and support the continent’s growing pharmaceutical market.