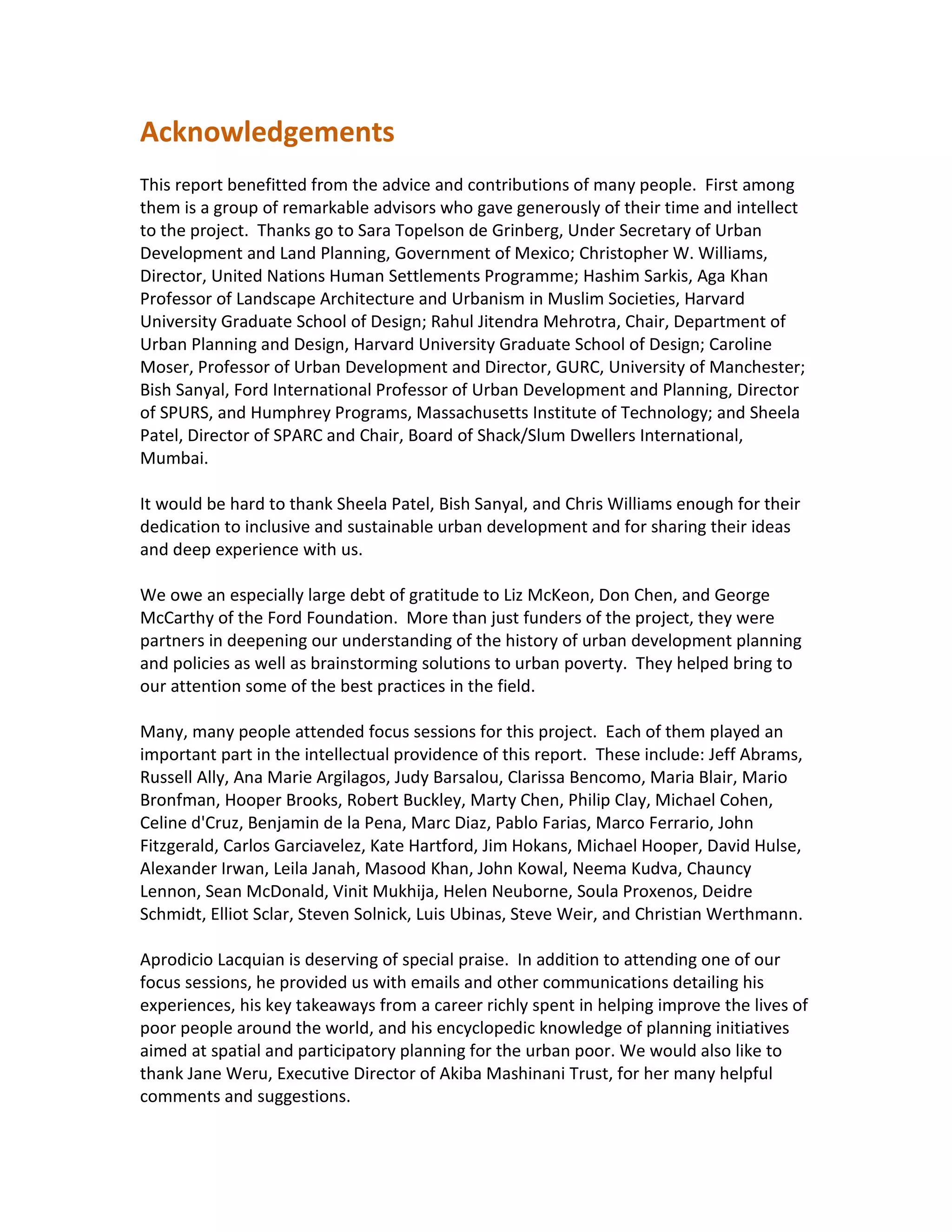

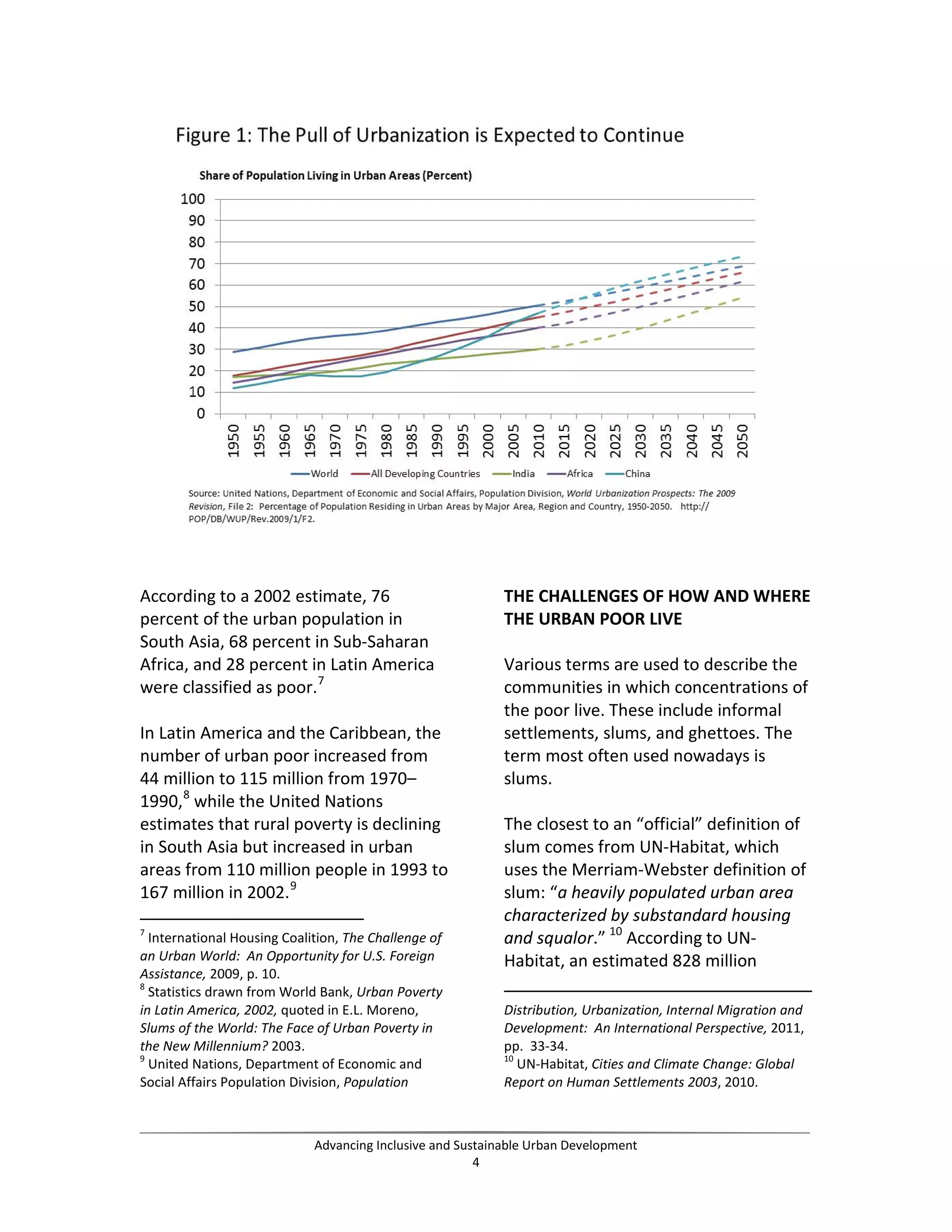

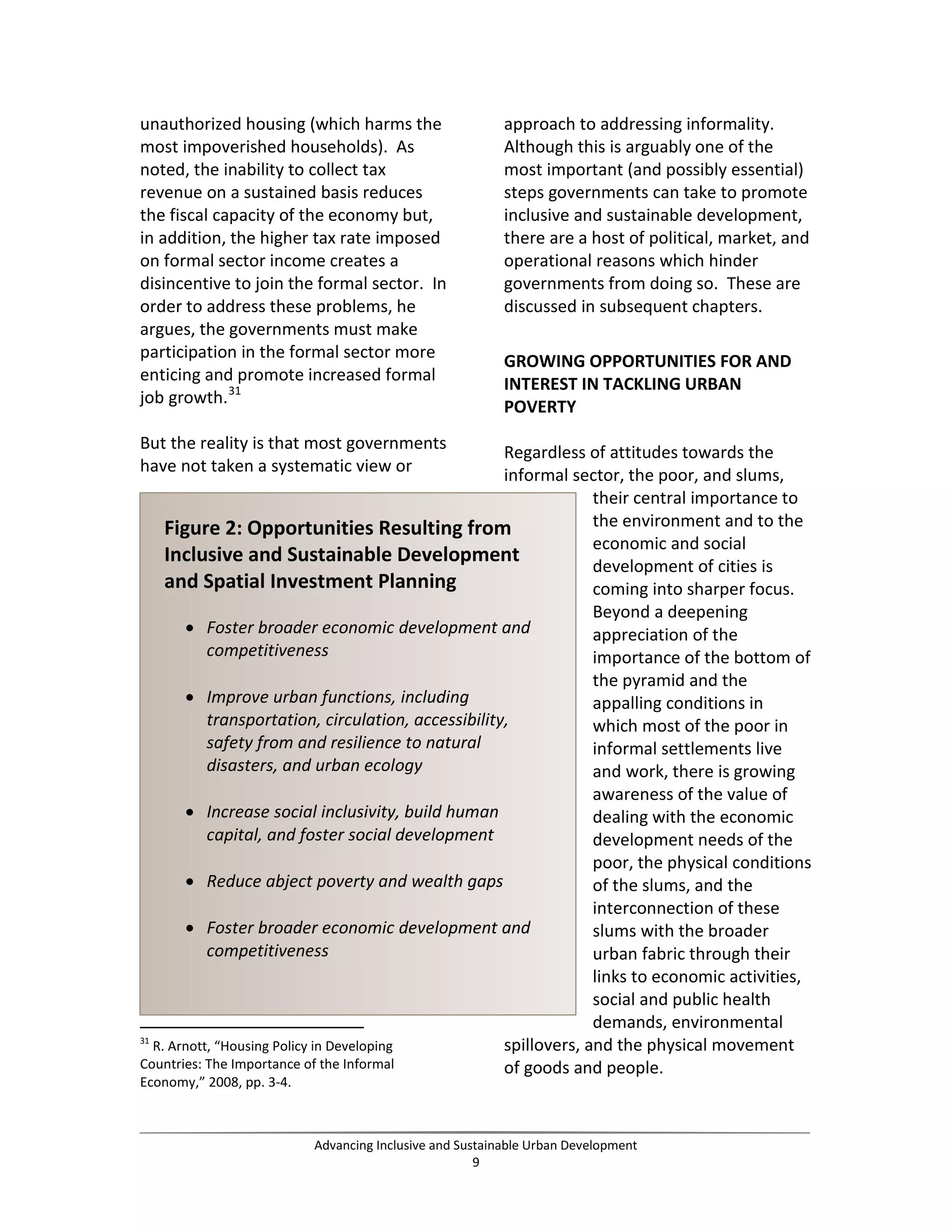

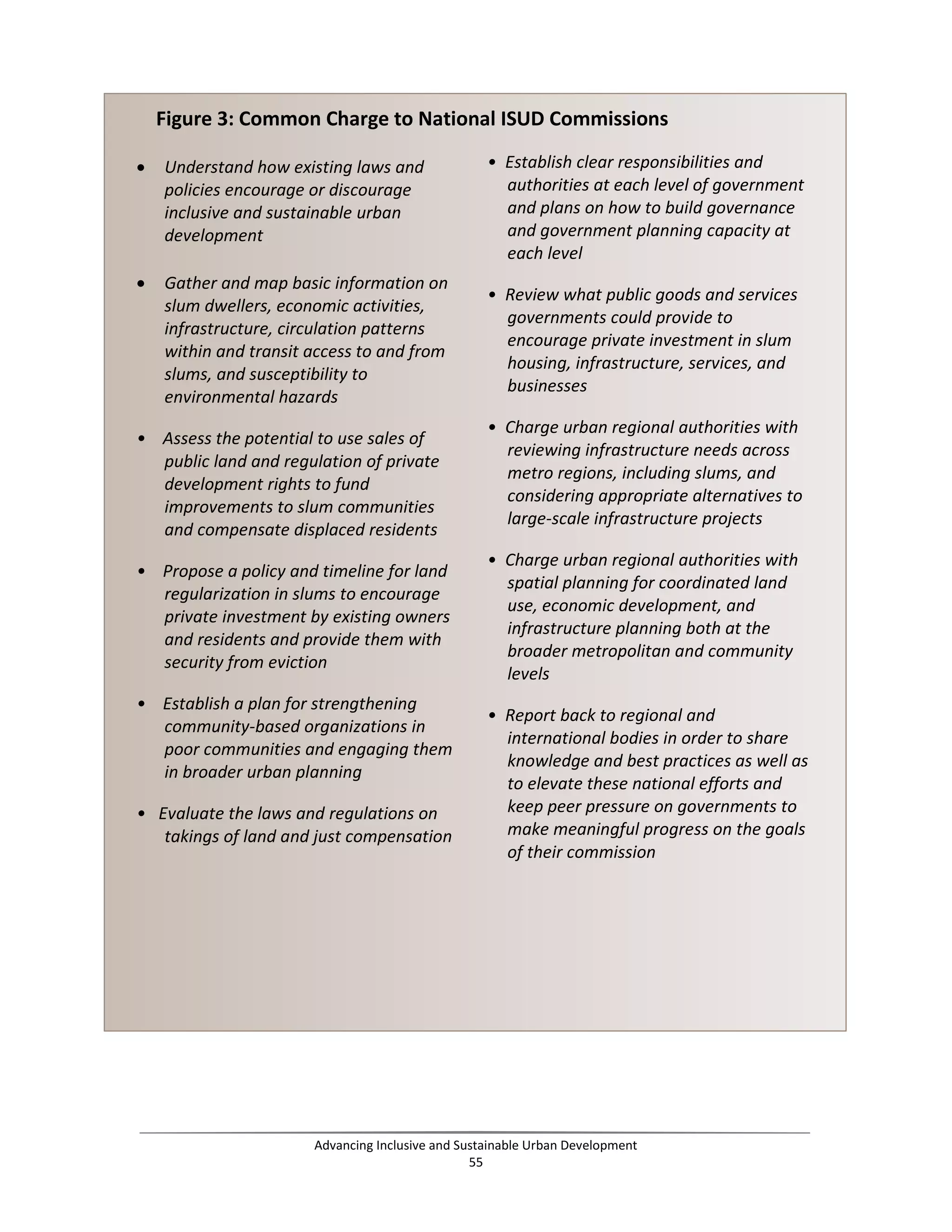

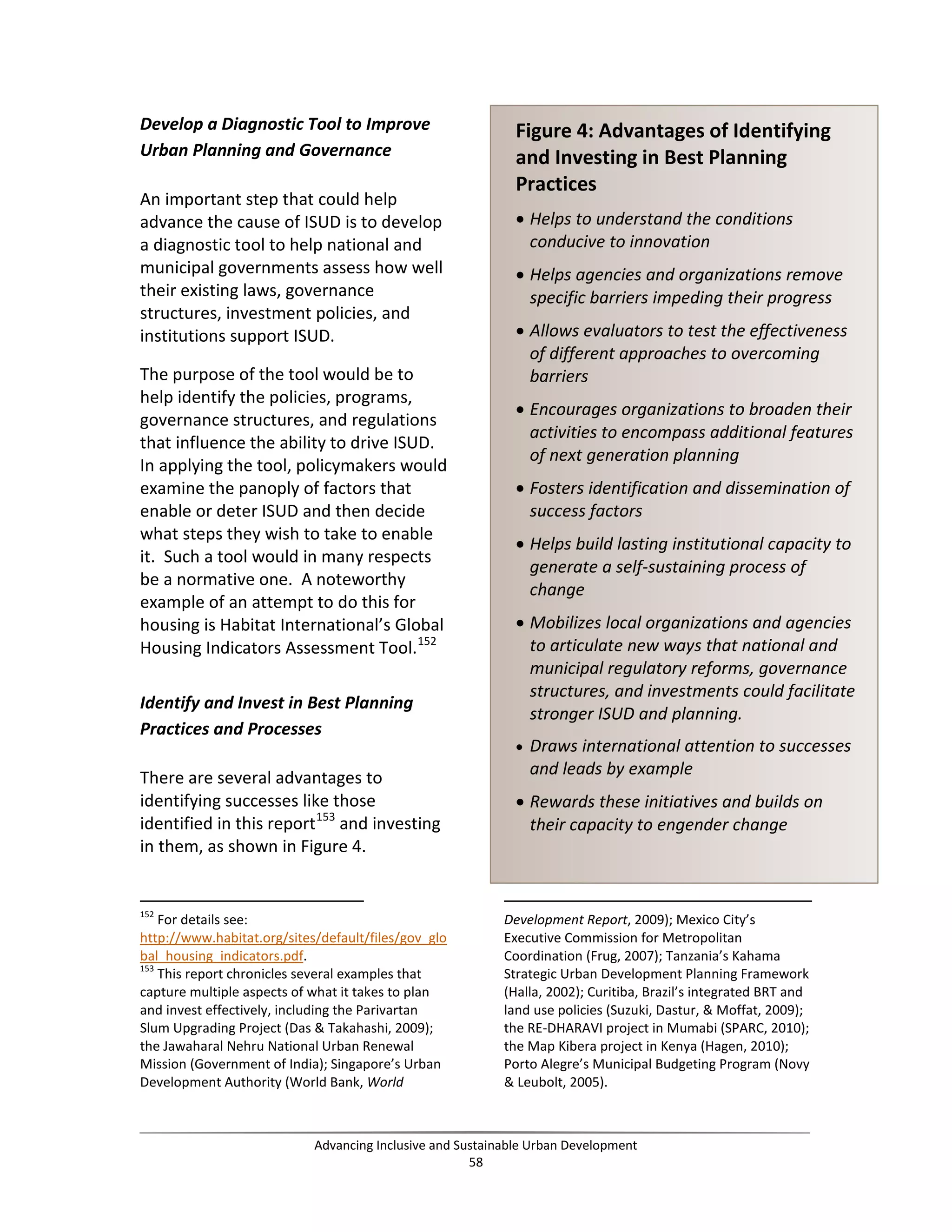

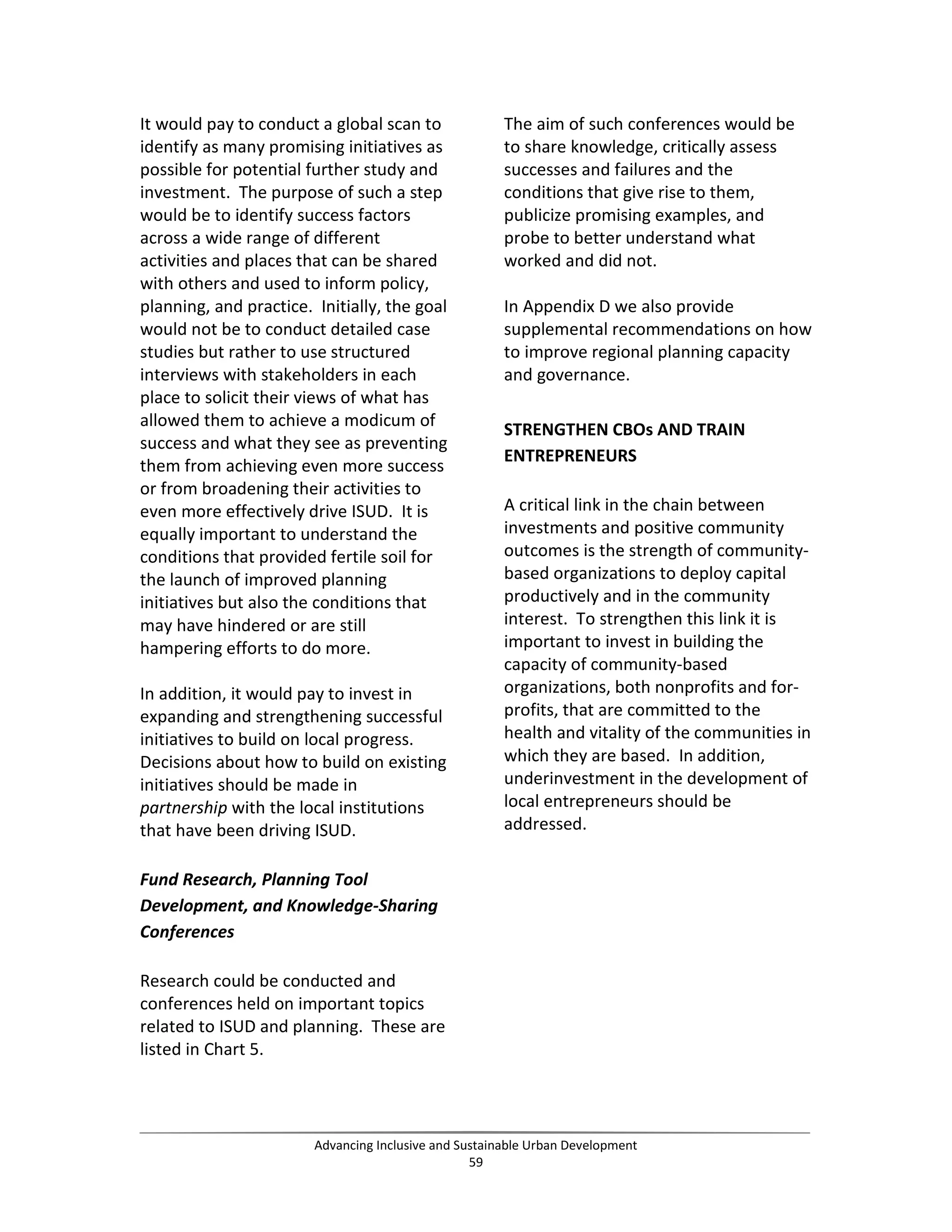

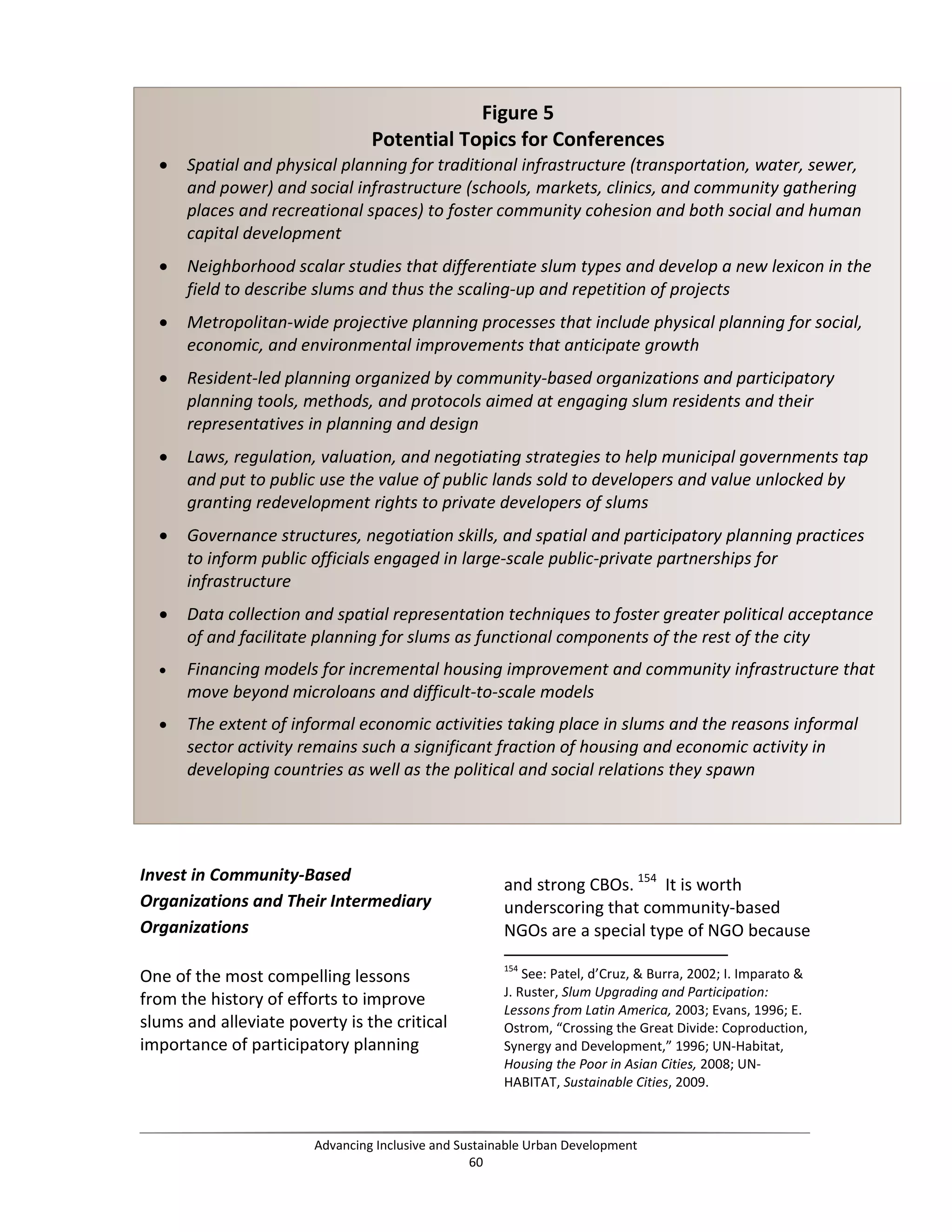

This report highlights the urgent need to address urban poverty and its manifestations in slums, particularly as global urbanization accelerates. It identifies deficiencies in current urban planning practices in developing countries and recommends strategies to improve planning, such as integrating spatial planning with infrastructure investments and enhancing community engagement. The report emphasizes that overcoming challenges like limited resources and political complexity is essential for achieving inclusive and sustainable urban development.