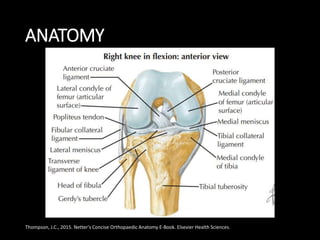

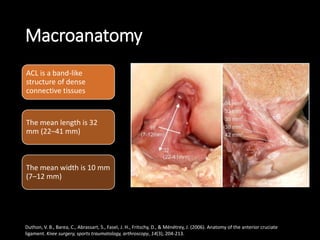

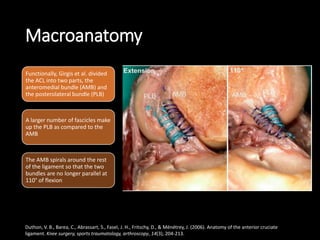

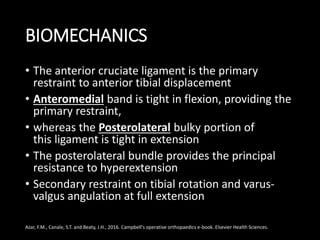

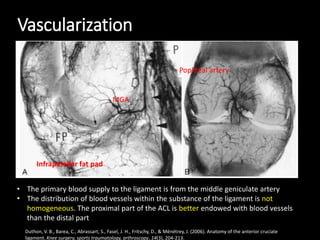

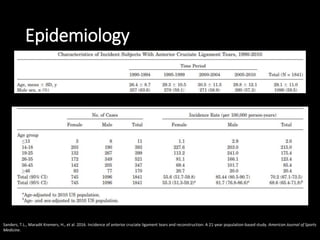

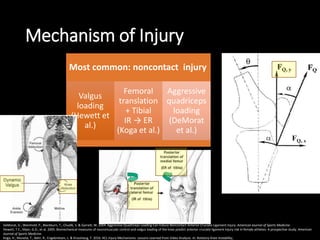

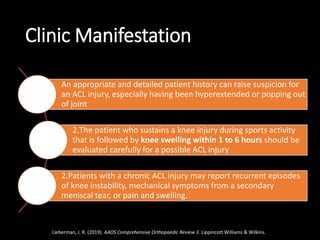

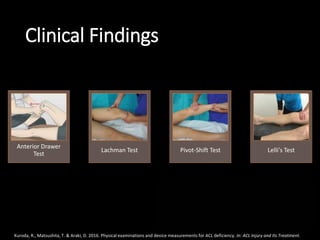

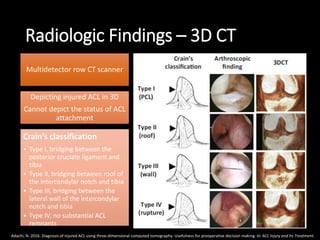

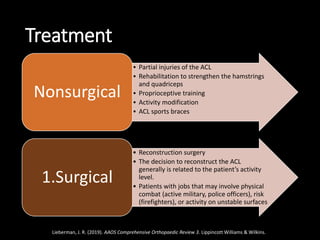

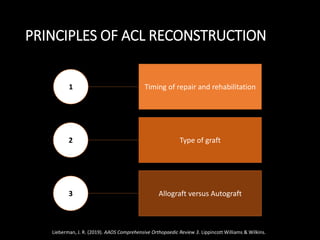

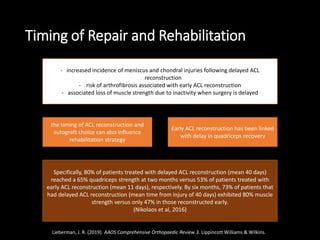

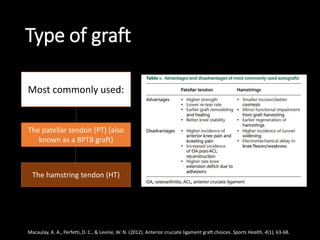

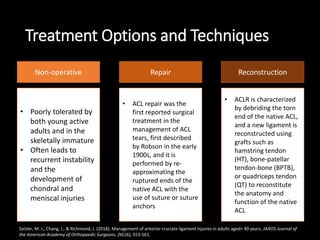

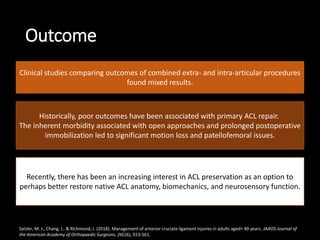

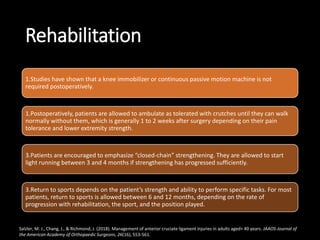

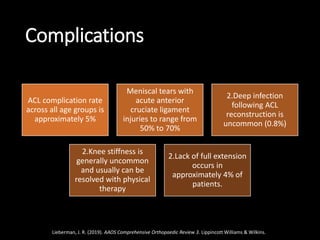

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a key ligament in the knee that prevents anterior tibial translation and rotational loads. It frequently tears during high-impact sports. The ACL inserts on the femur and tibia and is composed of two bundles that restrain movement differently based on knee flexion angle. While partial ACL tears may be treated nonsurgically, complete tears typically require surgical reconstruction using a graft to replace the torn ligament. Postoperative rehabilitation focuses initially on regaining range of motion and strength before gradually progressing to sport-specific activities.