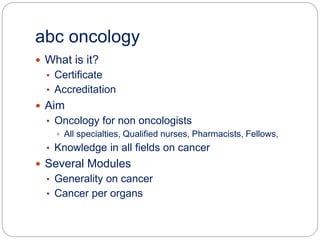

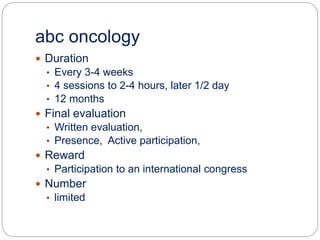

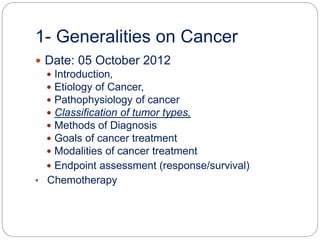

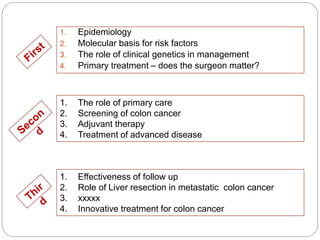

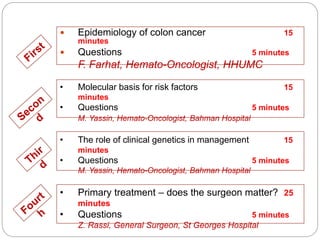

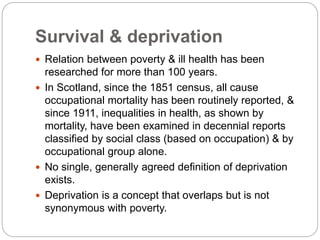

This document provides information about an oncology certification program called "abc in oncology". It discusses the program's aim to provide oncology knowledge to non-oncologists across various medical specialties. The program consists of several modules covering general cancer topics and specific cancer types. It is held every 3-4 weeks for a duration of 12 months, with evaluations to assess participation and knowledge. The document also includes an agenda and details for upcoming modules on colon cancer and breast cancer.