This document discusses two methods for declustering sample data to obtain a better estimate of the global mean: polygonal declustering and cell declustering.

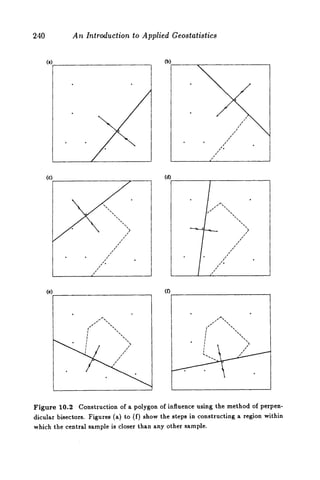

Polygonal declustering assigns each sample a polygon of influence based on its proximity to neighboring samples. The area of each polygon is used as the sample's declustering weight. Cell declustering divides the area into rectangular cells, with each sample receiving a weight inversely proportional to the number of samples in its cell. These methods are applied to sample data from Walker Lake to estimate the global vanadium and uranium means. Polygonal declustering performs better for vanadium, while both methods estimate uranium poorly due to sparse sampling in