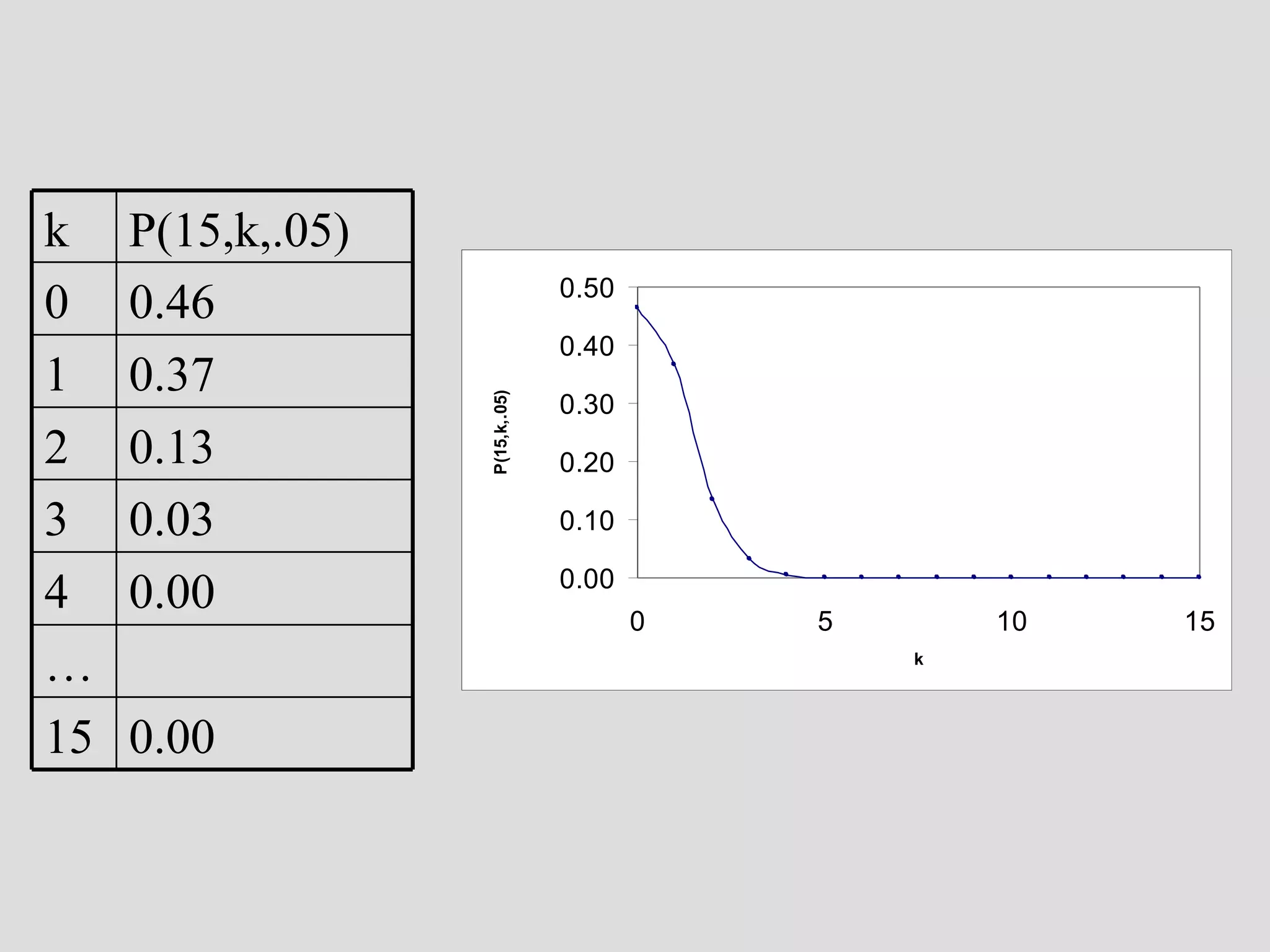

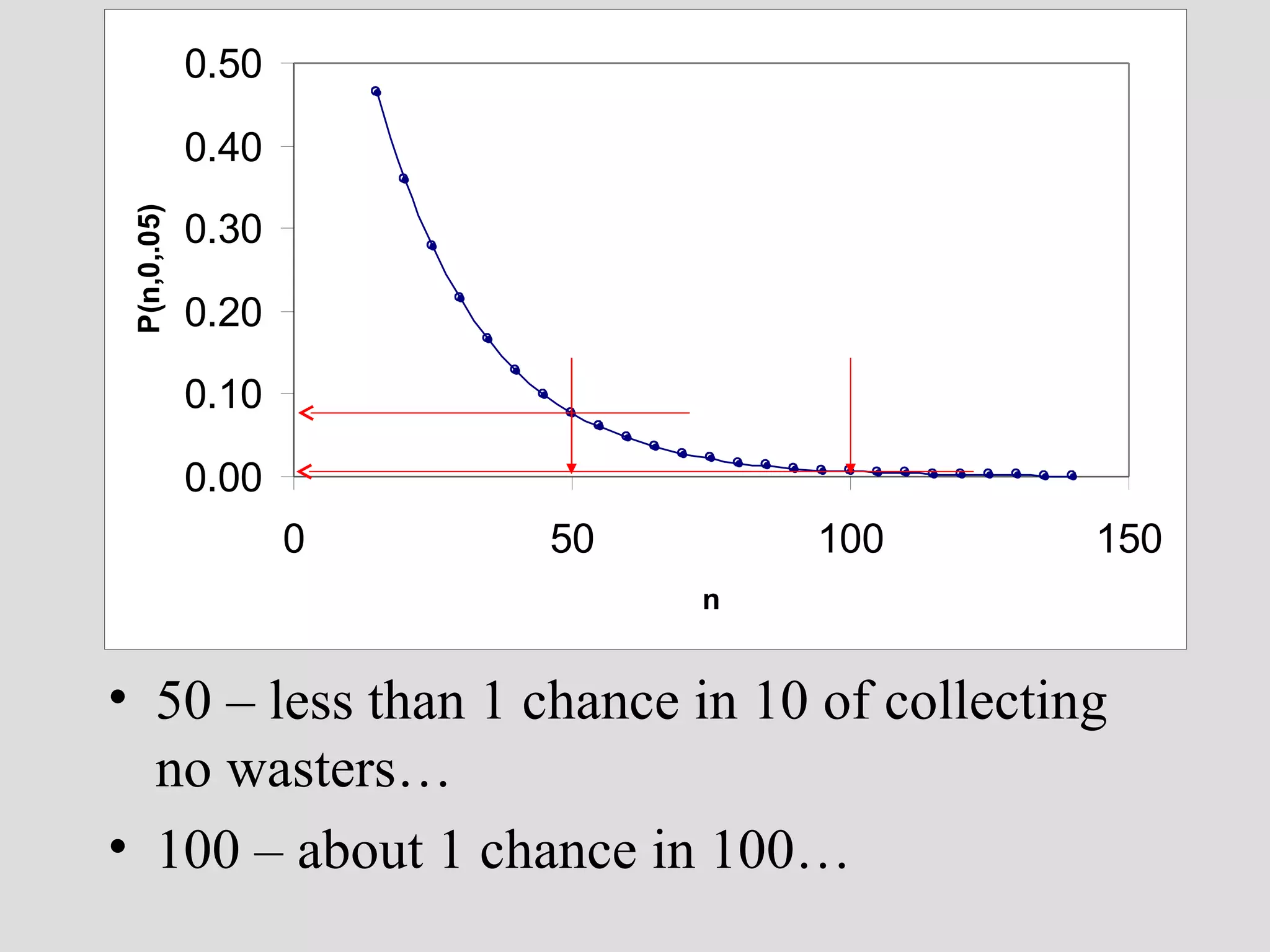

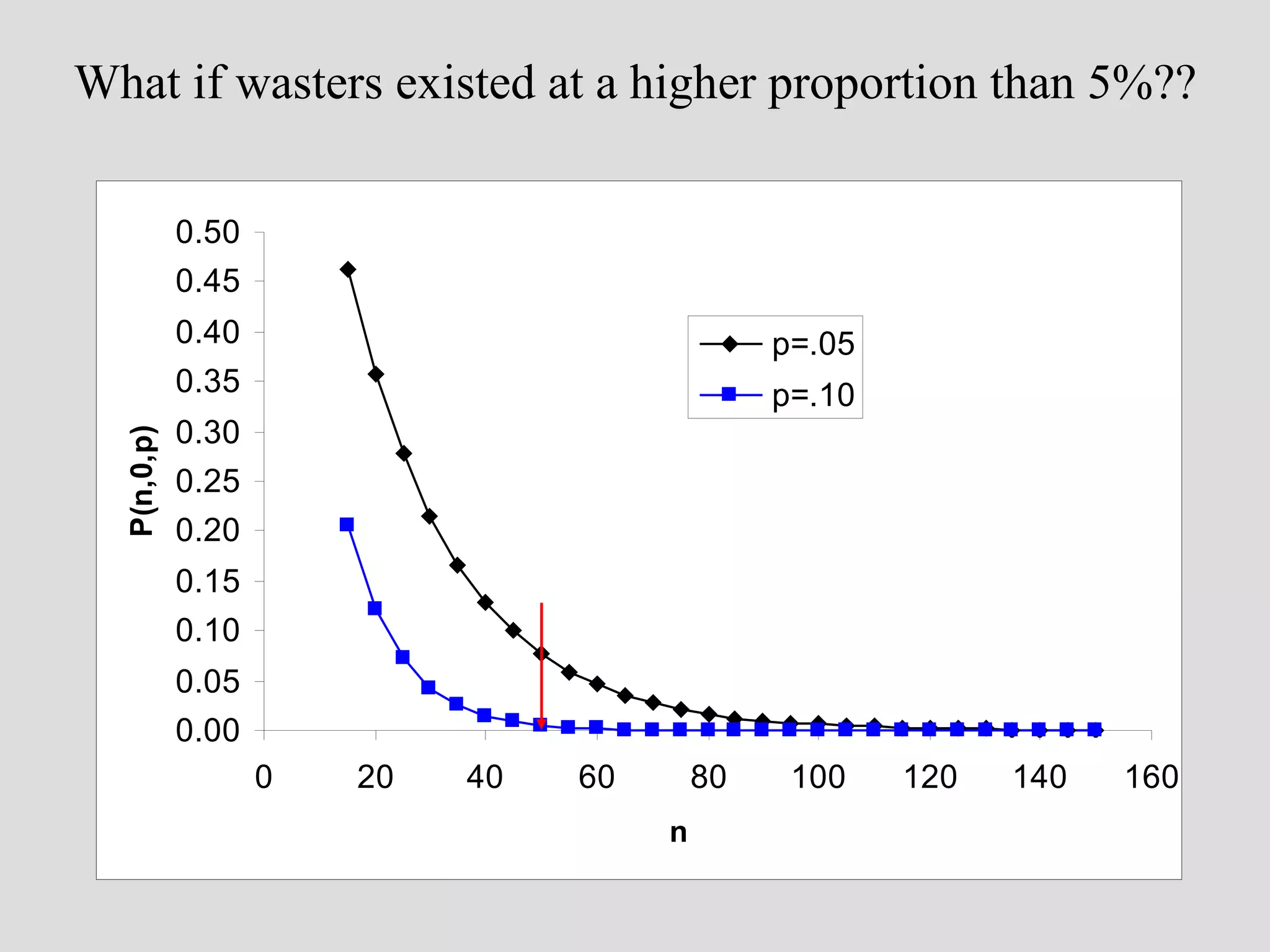

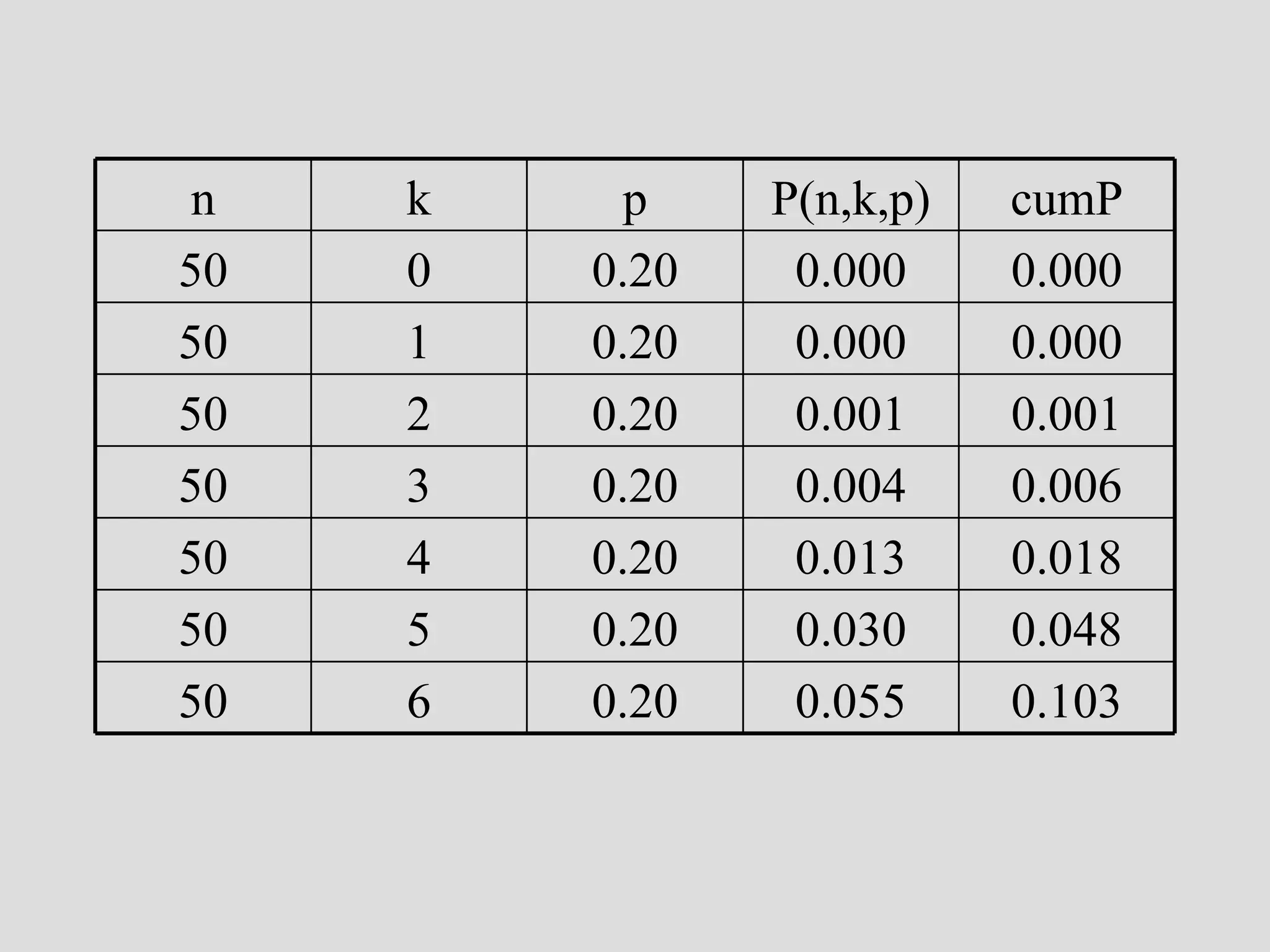

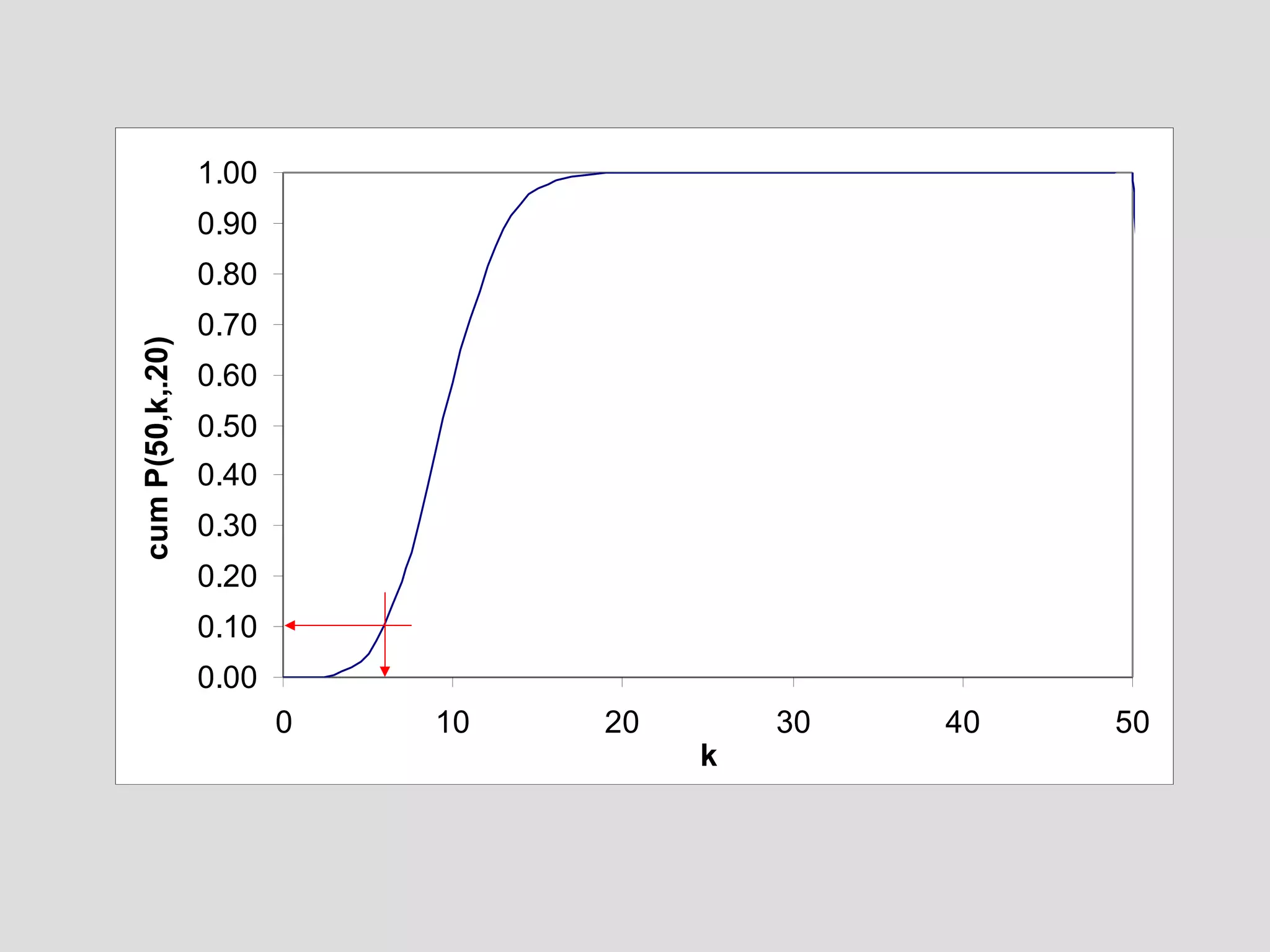

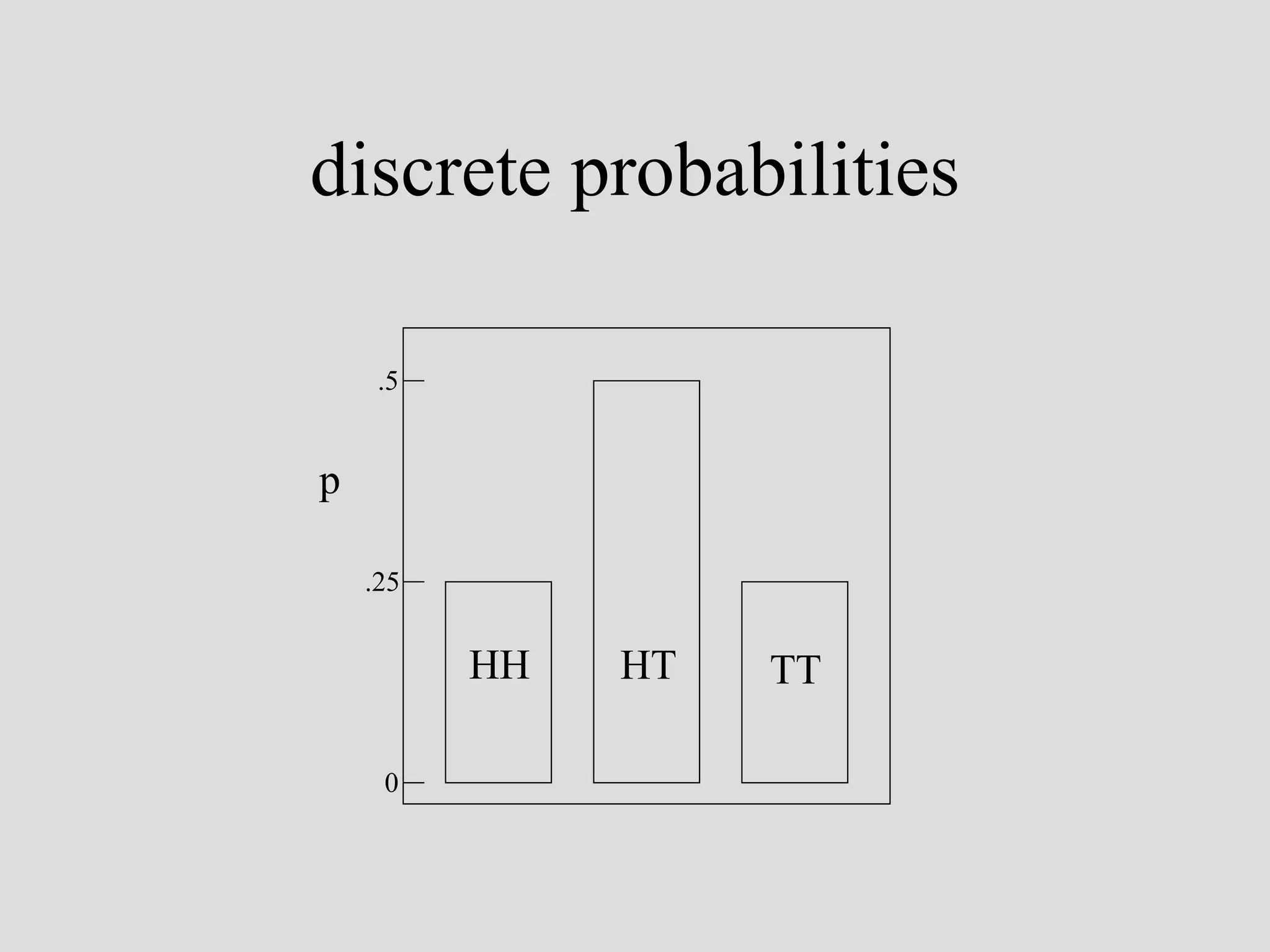

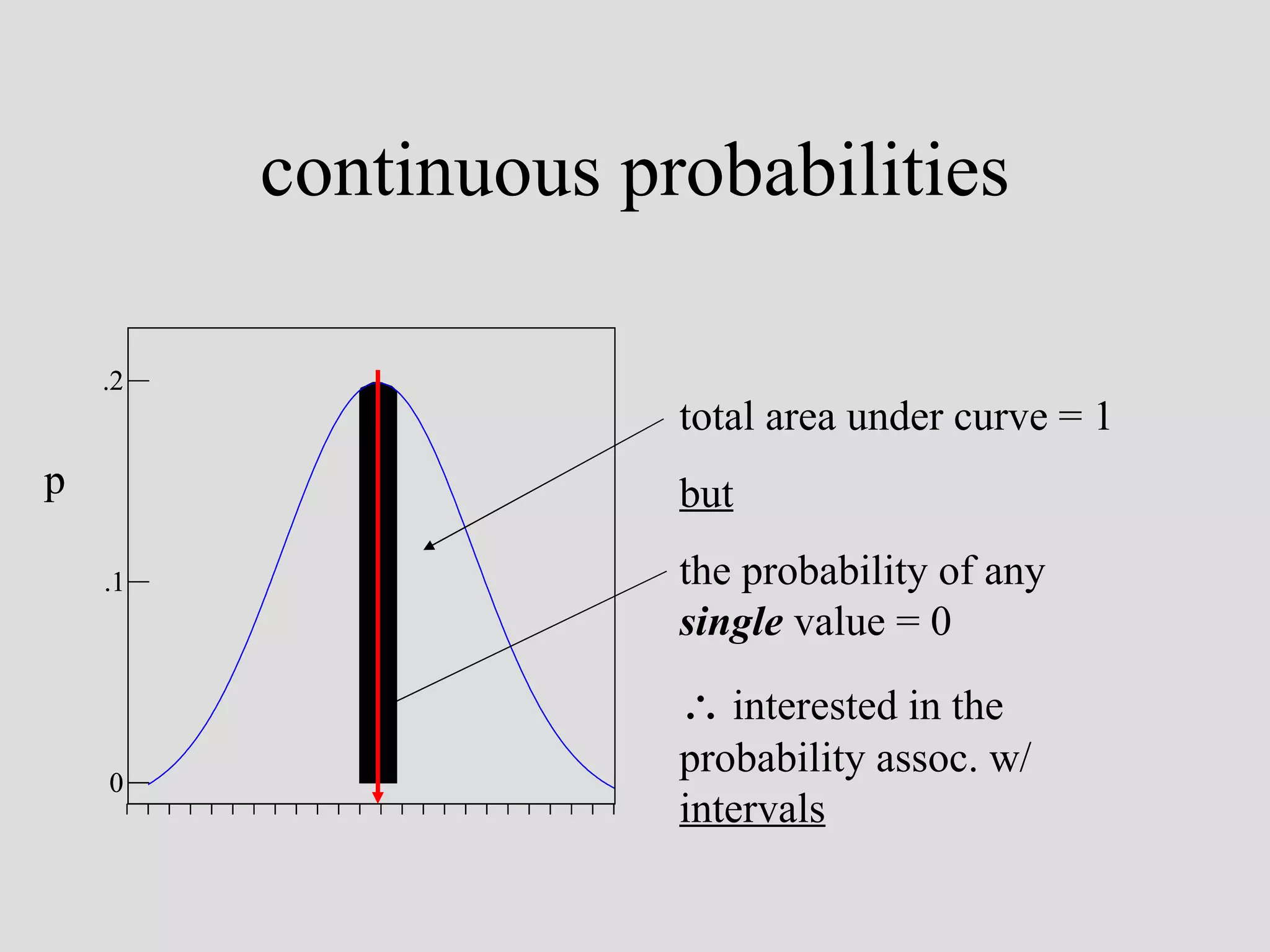

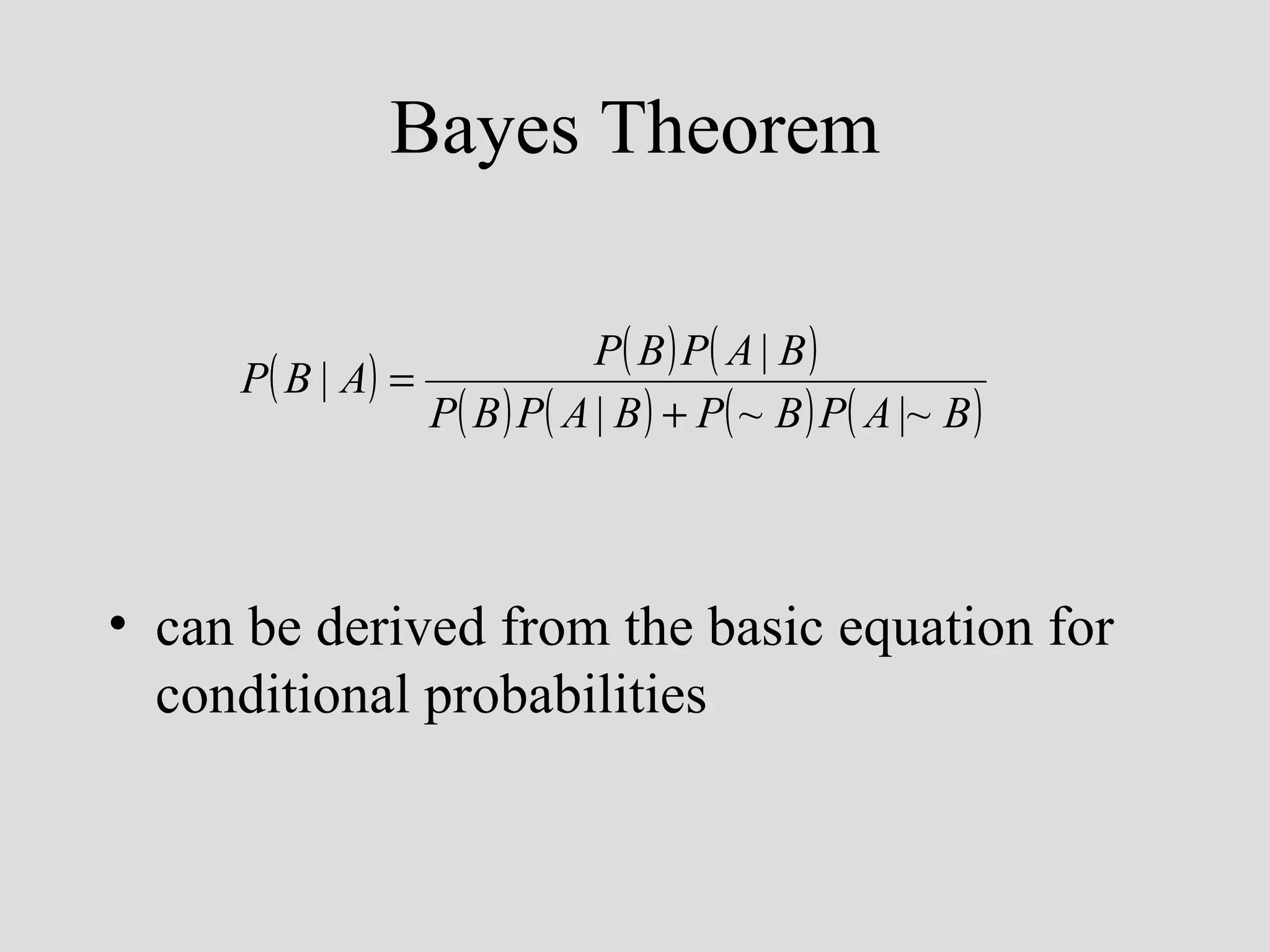

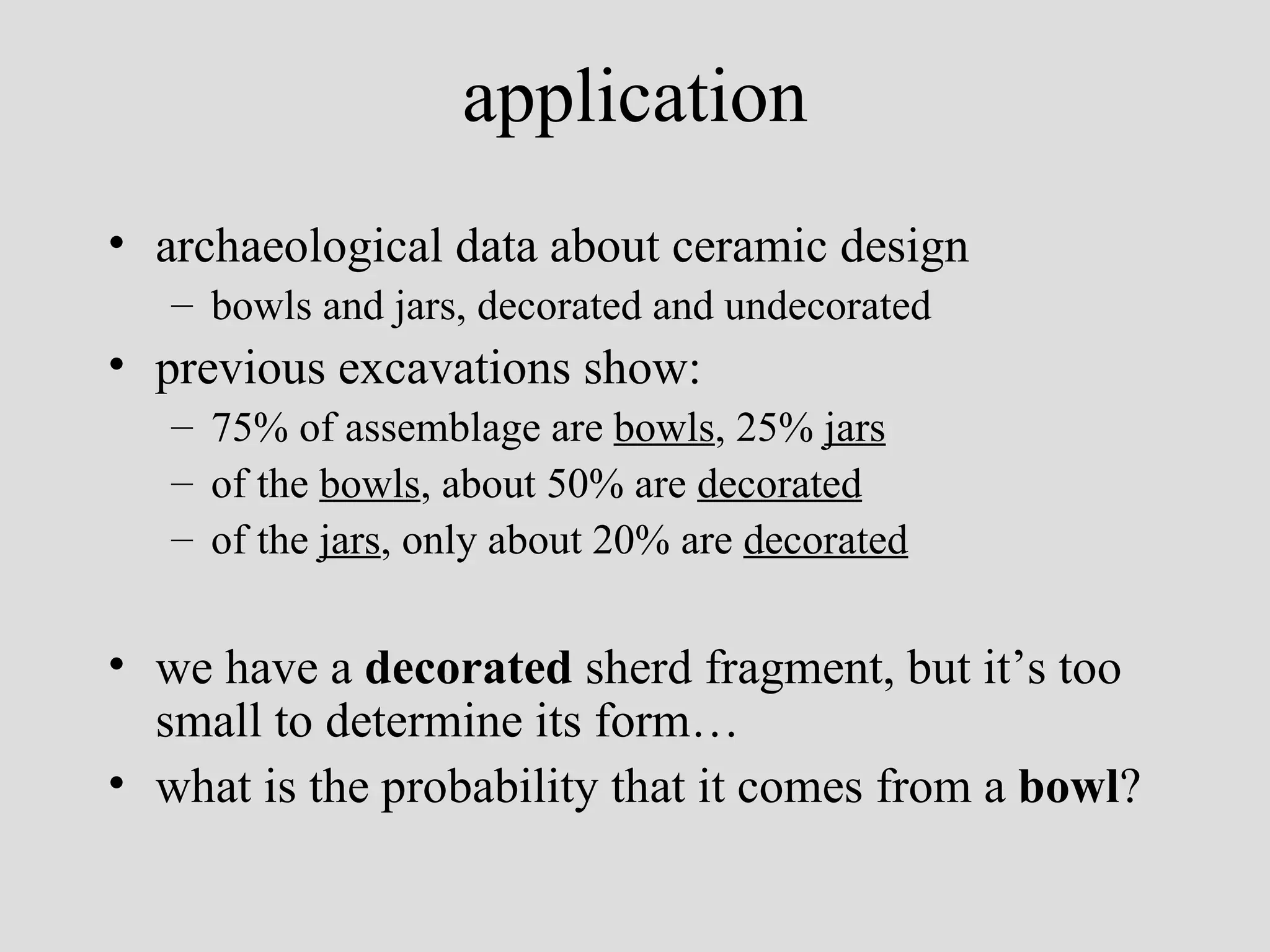

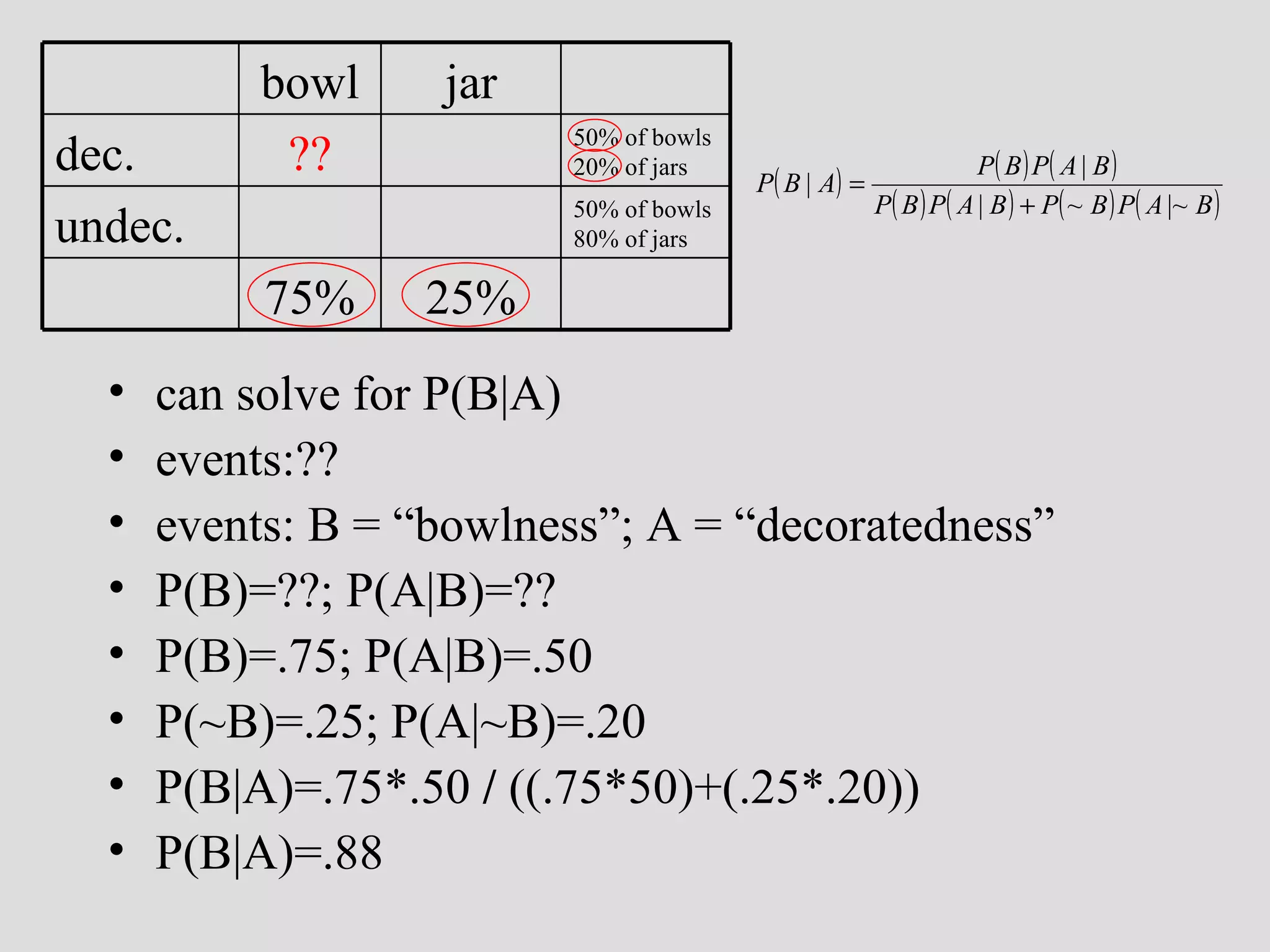

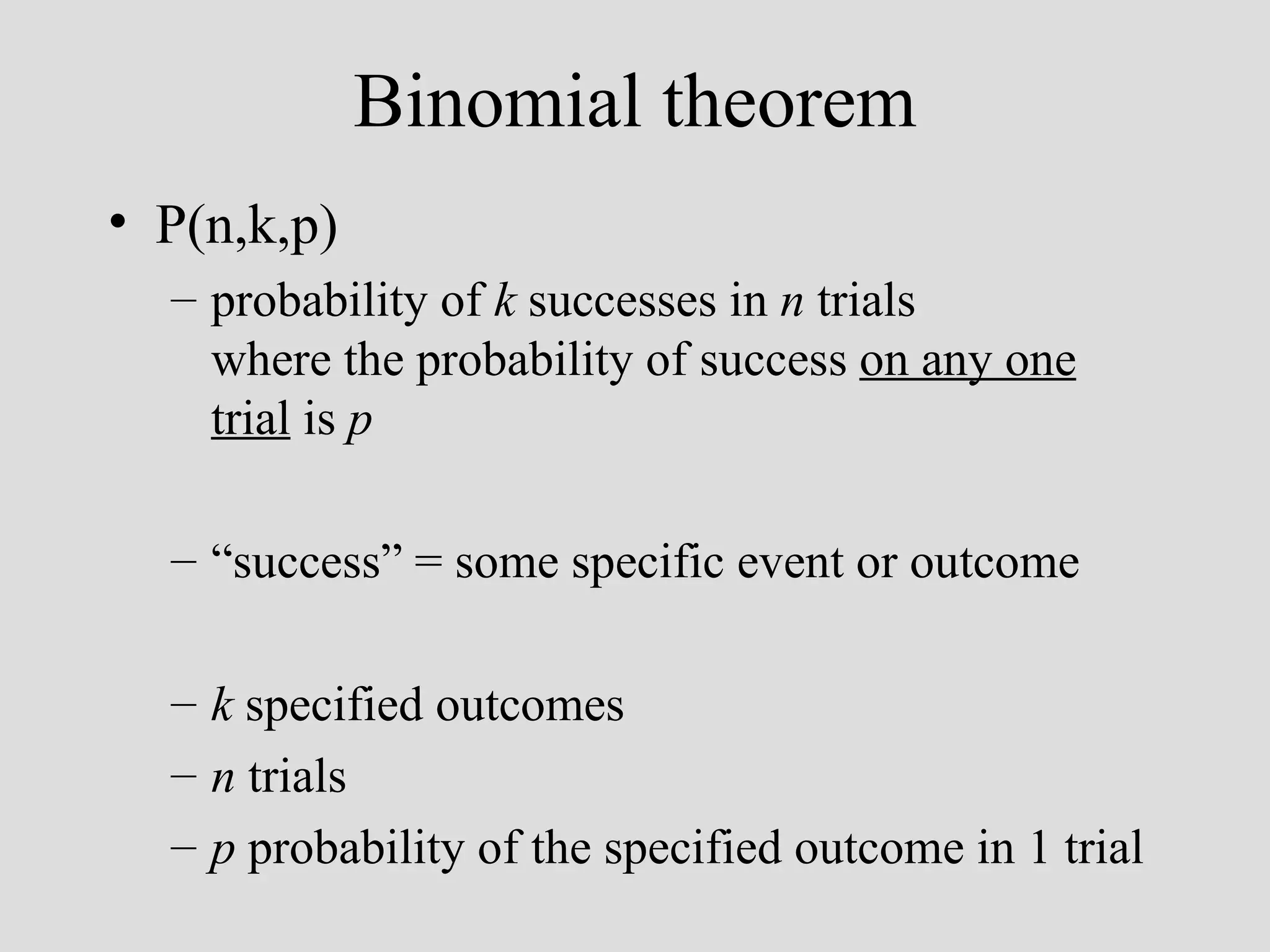

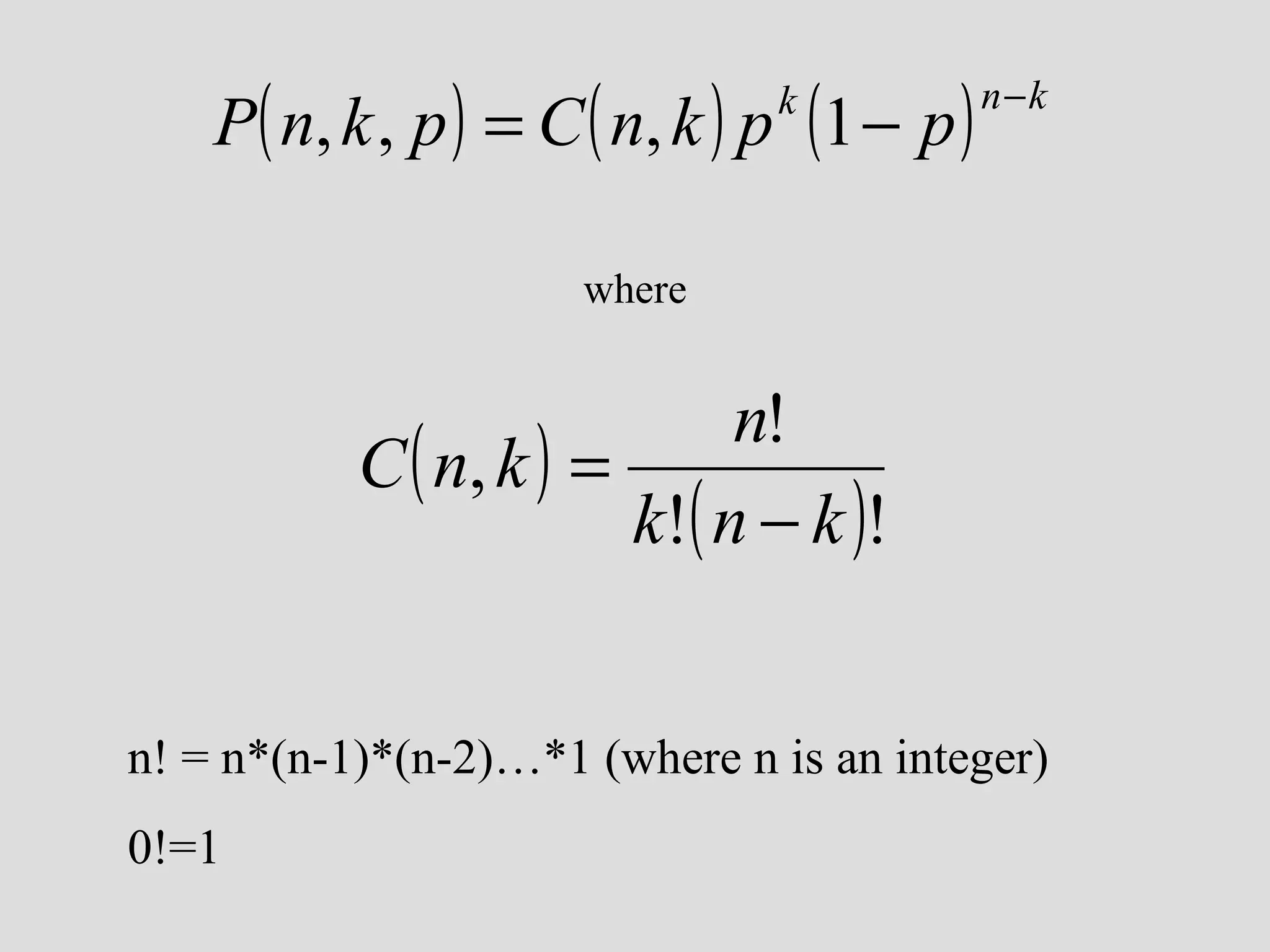

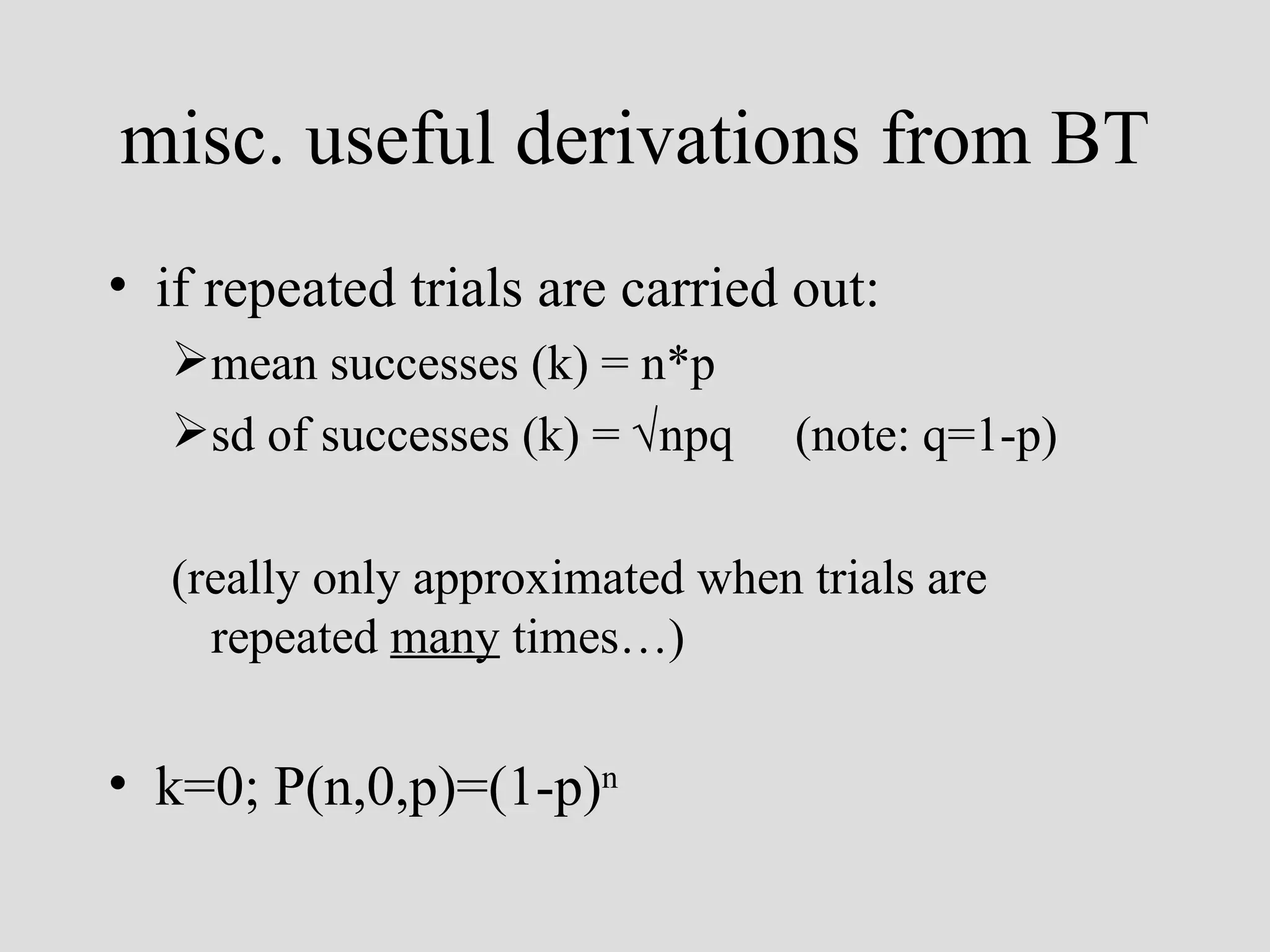

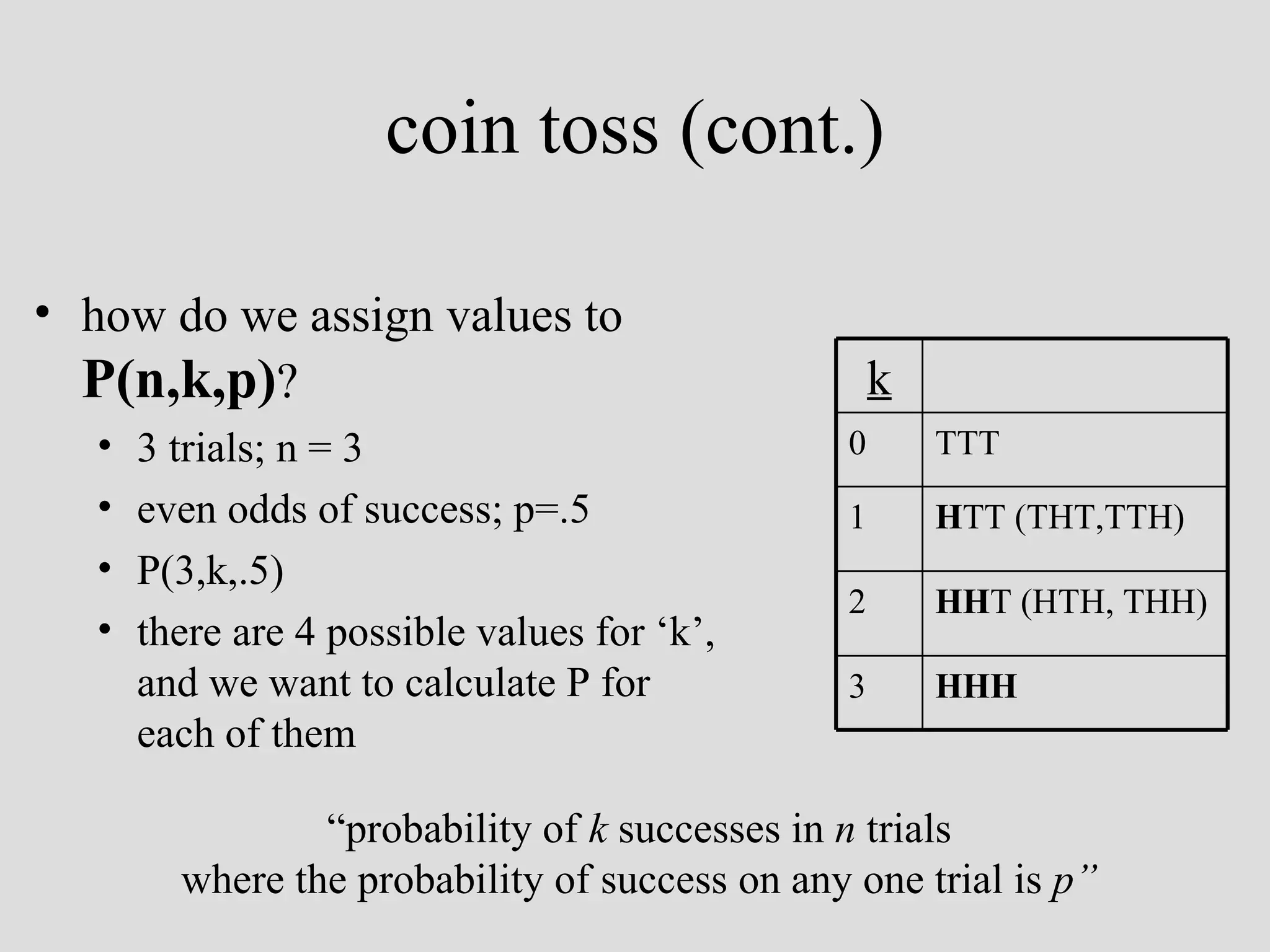

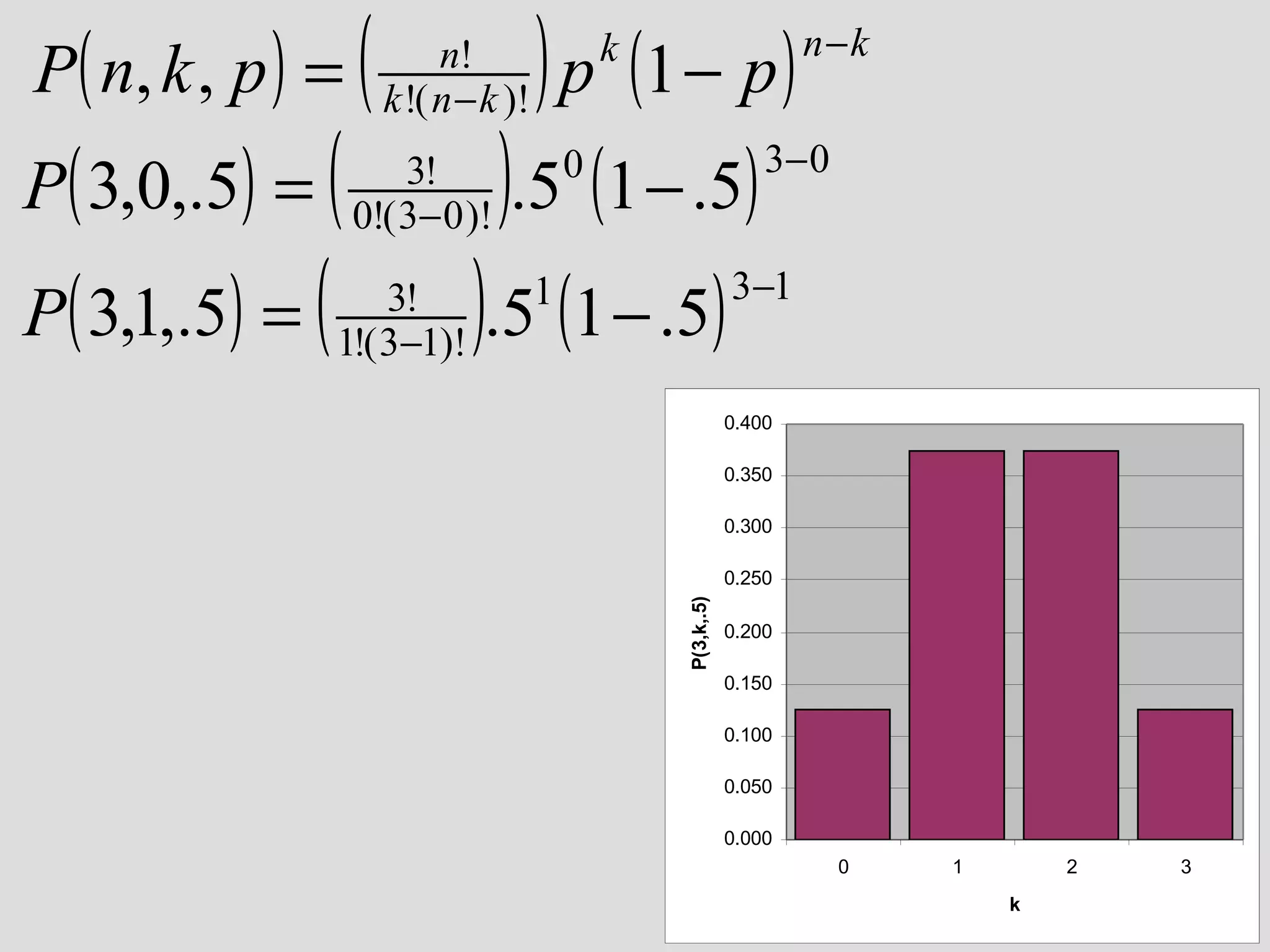

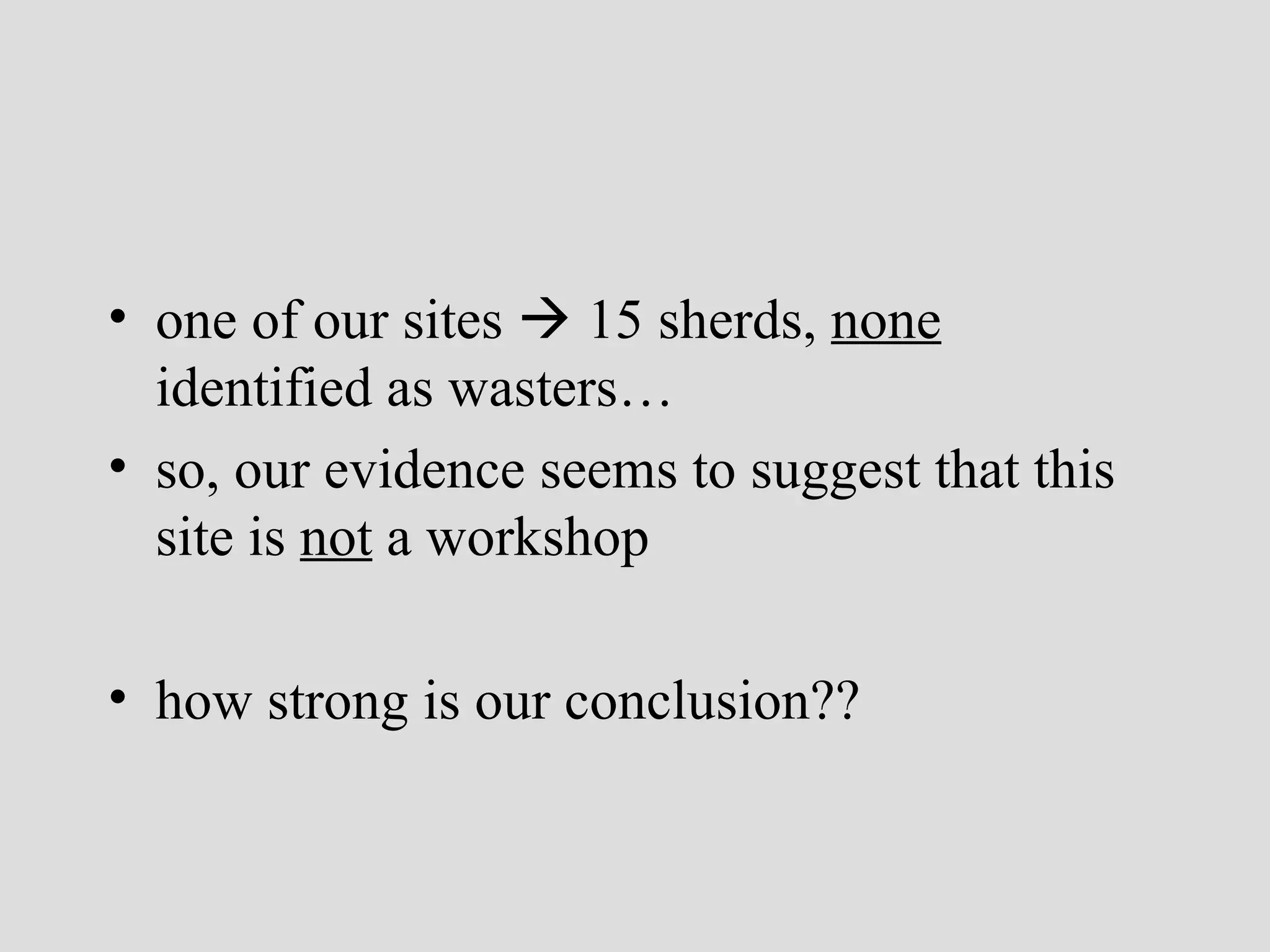

The document discusses key concepts in probability and their application to archaeological data analysis. It explains that probability can be assessed from both frequentist and Bayesian perspectives. The frequentist view assesses probabilities as objective frequencies of outcomes, while the Bayesian view incorporates prior knowledge. Several probability concepts are defined, including discrete vs. continuous probabilities and independent vs. conditional probabilities. The binomial theorem is introduced for calculating probabilities of outcomes from repeated trials. The document demonstrates how these probability concepts can help archaeologists evaluate sample sizes, absence of artifact types, and differences between sites while accounting for chance.

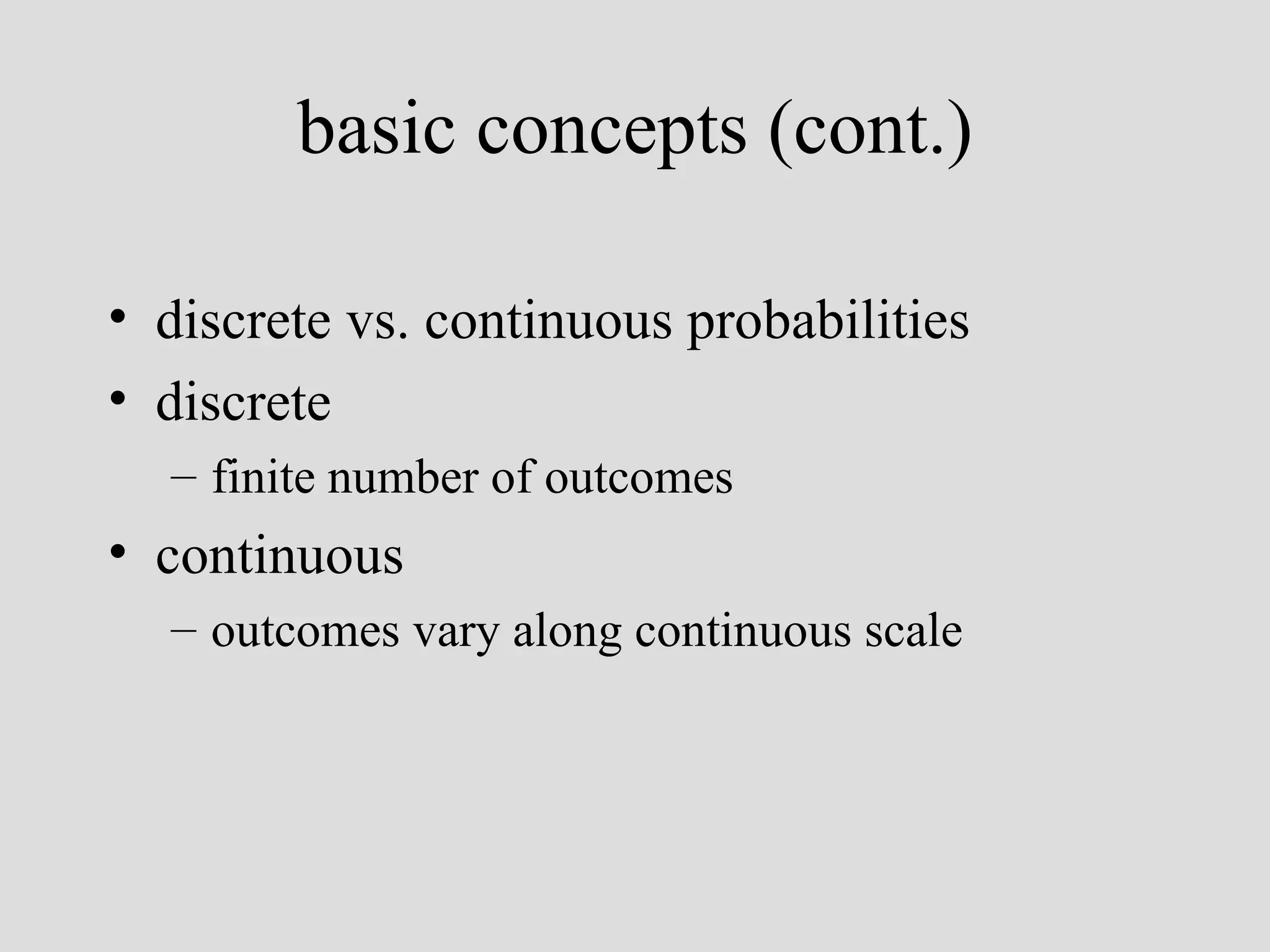

![reverse the logic: assume that it is a ceramic workshop new question: how likely is it to have missed collecting wasters in a sample of 15 sherds from a real ceramic workshop?? P(n,k,p) [ n trials, k successes, p prob. of success on 1 trial] P(15,0,.05) [we may want to look at other values of k…]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4probability-110311223321-phpapp01/75/4-probability-30-2048.jpg)