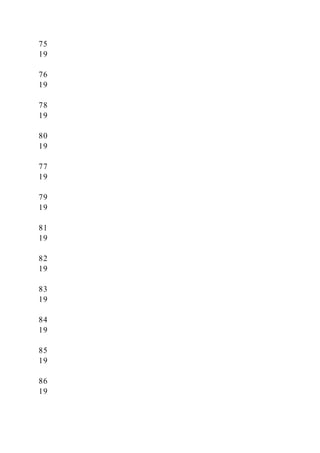

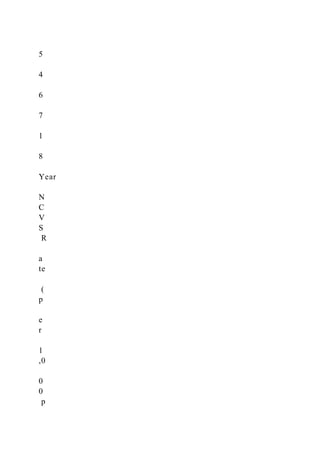

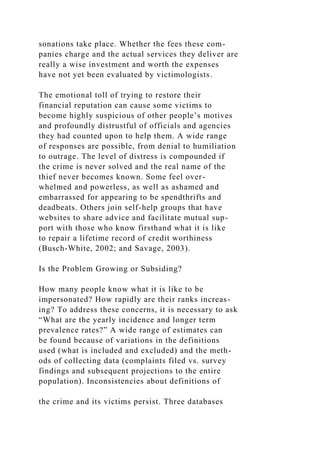

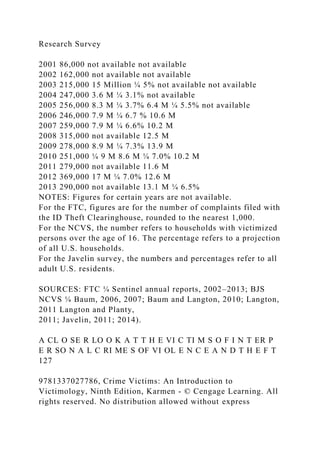

The document provides an overview of victimization statistics in the United States, emphasizing the importance of data from the FBI's Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). It discusses how these statistics inform about crime patterns, victimization rates, and societal responses to crime. The text also highlights the challenges and considerations in interpreting statistics accurately, including potential biases and the need for careful data collection and analysis.

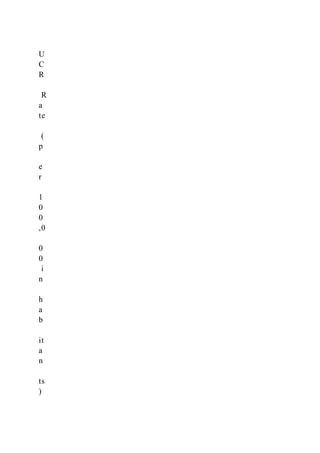

![measured because intentionally set fires might

remain classified by fire marshals as being “of

unknown origin.”) These eight crimes (in actual

practice, seven) are termed index crimes because

the FBI adds all the known incidents of each one

of these categories together to compute a “crime

index” that can be used for year-to-year and

place-to-place comparisons to gauge the seriousness

of the problem. (But note that this grand total is

unweighted; that means a murder is counted as

just one index crime event, the same as an

attempted car theft. So the grand total [like “com-

paring apples and oranges”] is a huge composite

that is difficult to interpret.)

The UCR presents the number of acts of vio-

lence and theft known to the authorities for cities,

counties, states, regions of the country, and even

many college campuses (since the mid-1990s; see

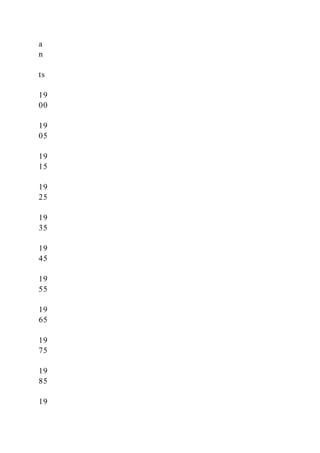

70 CH APT ER 3

9781337027786, Crime Victims: An Introduction to

Victimology, Ninth Edition, Karmen - © Cengage Learning. All

rights reserved. No distribution allowed without express

authorization.

F

O

S

T

E

R

,

C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3victimizationintheunitedstatesanoverviewchapte-221013111309-d2e70c3b/85/3Victimization-inthe-United-StatesAn-OverviewCHAPTE-docx-17-320.jpg)

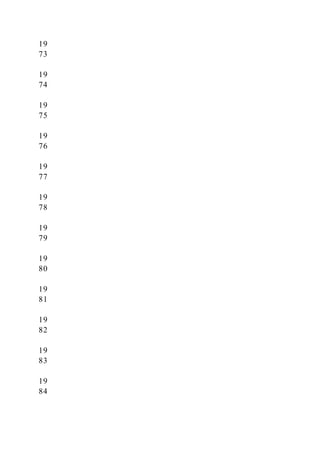

![assisted telephone interviews [CATI]) and mail-in

questionnaires. The response rate for individuals

who were invited to participate has held steady at

about 88 percent; in other words, 12 percent of the

people chosen for the study declined to answer

questions in 2010 as well as in 2013 (Truman,

2011; and Truman and Langton, 2014).

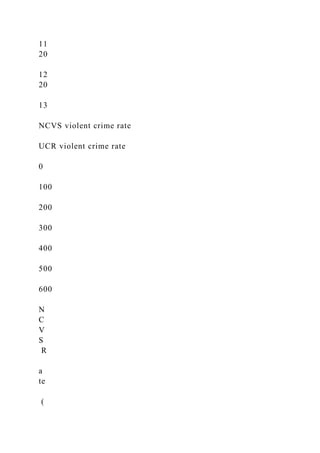

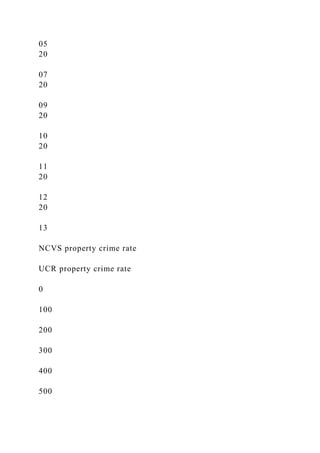

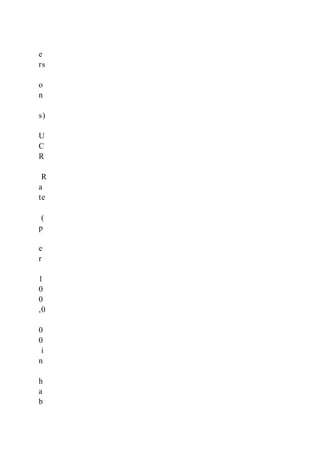

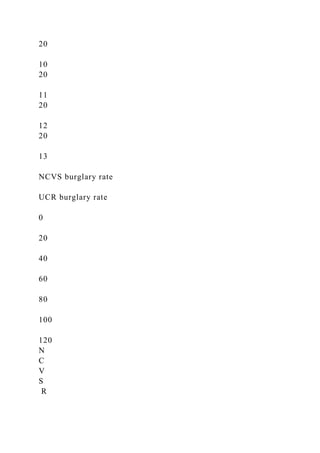

Comparing the UCR and the NCVS

For victimologists, the greater variety of statistics

published in the NCVS offer many more possibili-

ties for analysis and interpretation than the much

more limited data in the UCR. But both official

sources have their advantages, and the two can be

considered to complement each other.

The UCR, not the NCVS, is the source to turn

to for information about murder victims because

questions about homicide don’t appear on the

BJS’s survey. (However, two other valuable,

detailed, and accurate databases for studying homi-

cide victims are death certificates as well as public

health records maintained by local coroners’ and

medical examiners’ offices. These files may contain

information about the slain person’s sex, age, race/

ethnicity, ancestry, birthplace, occupation, educa-

tional attainment, and zip code of last known

address [for examples of how this non-UCR data

can be analyzed, see Karmen, 2006]).

The UCR is also the publication that presents

information about officers slain in the line of duty,

college students harmed on campuses, and hate

crimes directed against various groups. The UCR](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3victimizationintheunitedstatesanoverviewchapte-221013111309-d2e70c3b/85/3Victimization-inthe-United-StatesAn-OverviewCHAPTE-docx-37-320.jpg)

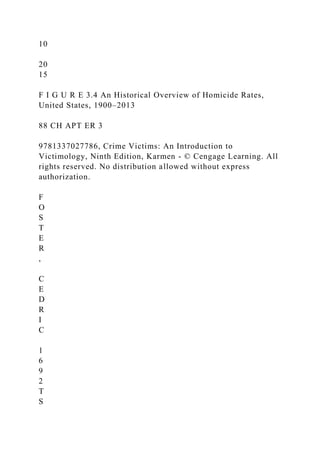

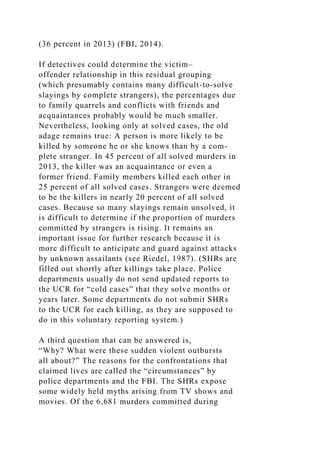

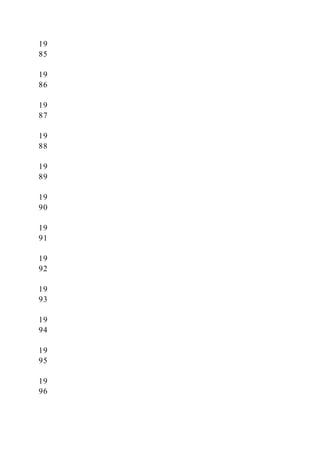

![misfortune.

■ What are the chances that a person will be

harmed by a violence-prone opponent at least

once during his or her entire life (not just in a

single year) [incidence rate], or during previ-

ous years [prevalence rate]? Cumulative risks

estimate these lifetime likelihoods by project-

ing current situations into the future.

■ Is violence a growing problem in American

society, or is it subsiding? Trend analysis

provides the answer by focusing on changes

over time.

■ Does violent crime burden all communities

and groups equally, or are some categories

of people more likely than others to be

held up, physically injured, and killed?

Differential risks indicate the odds of an

unwanted event taking place for members of

one social demographic group as compared

to another.

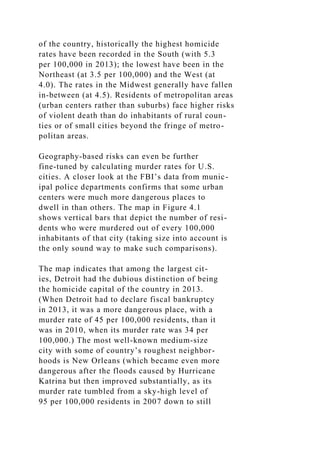

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To understand the meaning of differential risks.

To appreciate the complications of making international

comparisons.

To discover which countries and which cities across the

globe have the highest and lowest homicide rates.

To use official statistics to spot national trends in murders,

aggravated assaults, and robberies in recent decades.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3victimizationintheunitedstatesanoverviewchapte-221013111309-d2e70c3b/85/3Victimization-inthe-United-StatesAn-OverviewCHAPTE-docx-114-320.jpg)

![authorization.

F

O

S

T

E

R

,

C

E

D

R

I

C

1

6

9

2

T

S

reporting rate to the police had slipped to a mere

9 percent (although nearly 90 percent reported the

misuse to a credit card company or bank, 9 percent

contacted a credit bureau, and 6 percent contacted

one of the credit monitoring services [Harrell and

Langton, 2013]).

Who Faces the Greatest Risks?

Several obstacles hamper attempts to derive accu-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3victimizationintheunitedstatesanoverviewchapte-221013111309-d2e70c3b/85/3Victimization-inthe-United-StatesAn-OverviewCHAPTE-docx-258-320.jpg)